Frank Wickware

“Cannon Ball Redding and others of days gone by had plenty of speed, but Frank Wickware, speed ball artist from Coffeyville, Kan., was recognized as the king until LeRoy (Satchel) Paige arrived on the scene with his fast ball.” — Chicago Defender, 19301

Frank Wickware was one of the premier Negro pitchers from 1910 to 1920. The tall right-hander with the fearsome fastball was among the preliminary candidates considered in 2006 for election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues.2 Although he was not selected for induction, he did get inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011.3 Wickware lived a turbulent life, on and off the baseball diamond.

Frank Wickware was one of the premier Negro pitchers from 1910 to 1920. The tall right-hander with the fearsome fastball was among the preliminary candidates considered in 2006 for election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues.2 Although he was not selected for induction, he did get inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011.3 Wickware lived a turbulent life, on and off the baseball diamond.

Born on March 18, 1888, in Girard, Kansas, Frank Ellis Wickware was the youngest child of Eldon and Mollie (Love) Wickware.4 The family moved to Coffeyville about 1906.5 On July 29, 1907, Frank threw a no-hitter for a Muskogee (Oklahoma) team against a Fort Worth squad.6 He pitched for the Dallas Black Giants in 1908 and 1909, and was nicknamed “Zig Zag.”7

Rube Foster, the great pitcher and manager, hired Wickware to pitch for the Chicago Leland Giants in 1910, and under Foster’s tutelage he developed into a star. Wickware threw a two-hit shutout in Oklahoma City on April 24.8 In Chicago he hurled a no-hitter and struck out 14 Chicago Athletics on June 5, and he beat the Kansas City Giants with a three-hitter on June 26.9 He defeated the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Red Roses, a Class-B minor-league team, with a four-hit shutout on September 19 in Atlantic City.10

The 1910 Leland Giants featured future Hall of Famers Pete Hill in center field and John Henry Lloyd at shortstop. Bruce Petway, the team’s backstop, was regarded as the best defensive catcher in Negro baseball. Unofficially, the team compiled an astounding 123-6 won-lost record, and Wickware posted an 18-1 record, through games of September.11 Against tougher competition in Cuba (October to November) and in the California Winter League (November to February), the team won 15, lost 11, and tied 3.12

In 1911 Foster organized his own team called the Chicago American Giants. Wickware pitched for both the Leland Giants and the American Giants in 1911.13 In early 1912 he pitched in Cuba for the Fe team14 and rejoined the American Giants upon his return to the United States. On May 19 he shut out the Brooklyn Royal Giants in Chicago, and in August the Royal Giants “paid a large sum to Rube Foster” to acquire him.15

As a Royal Giant, Wickware faced Dick “Cannonball” Redding of the New York Lincoln Giants in both games of a doubleheader on August 25, 1912. Both pitchers threw two complete games that day; Wickware won the first game, 3-2, and Redding won the second, 3-0.16 In a rematch two weeks later, Wickware outdueled Redding, 1-0.17 That winter Wickware pitched for the Lincoln Giants in Cuba.18

After starting the 1913 season with the Royal Giants, Wickware jumped in May to the Schenectady (New York) Mohawk Giants, a Negro team assembled by Bill Wernecke, a White businessman.19 The Mohawk Giants were well supported by Schenectady, a nearly all-White city. On May 25 a crowd of 3,500 turned out to see Wickware throw a five-hitter with 11 strikeouts against the visiting Smart Sets of Paterson, New Jersey.20 On June 7, he lost a pitchers’ duel, 2-1, to future Hall of Famer Cyclone Joe Williams and the Lincoln Giants.21

Wickware mixed a deceptive change-of-pace and sharp curveball with his dominating fastball, so that batters had no idea what was coming.22 After receiving the ball, he might quick-pitch it or hold it a while before firing it with no windup, so that batters had no idea when it was coming.23 He kept hitters off balance with these tricks he learned from Rube Foster.24

On Sunday, July 13, before nearly 6,000 fans in Schenectady, Wickware hurled a three-hit shutout in a 4-0 victory over the Troy Trojans of the Class-B New York State League.25 “Wickware struck out eleven players and called the fielders in after two were down in the ninth. He then struck out the last batter,” a Black newspaper reported.26 Wernecke profited financially when Wickware put on a show in front of a large Sunday crowd.

The Lincoln Giants and Foster’s American Giants were scheduled to play a five-game championship series in New York City beginning July 17, 1913. Rod McMahon, owner of the Lincoln Giants, paid Wickware $100 in advance to pitch for his team in the series, but Wickware showed up to the first game in an American Giants uniform. Foster insisted that Wickware was pitching for him. The game was called off after McMahon and Foster argued for more than an hour.27 Wickware would pitch for neither team in the series.

With Wickware AWOL and unavailable to pitch in Schenectady on Sunday, July 20, the irritated Wernecke went to the police with Henry Kearney, who swore out a warrant against Wickware for skipping out on a $10 board bill from Kearney’s boarding house. Wickware, though, returned in time for the Sunday game. Despite the outstanding warrant for his arrest, he pitched against the Utica Utes of the New York State League, and his ninth-inning hit gave the Mohawk Giants a 4-3 victory before an enthusiastic crowd of 6,000. The next day he was arrested and pleaded guilty to the larceny charge, and his $25 fine was paid by one of his teammates.28

On August 3, 1913, Wickware spun a three-hit shutout in Schenectady with 15 strikeouts in a 5-0 triumph over the Albany Senators of the New York State League.29 On August 12 the Brooklyn Royal Giants were aided by seven Mohawk Giants errors, including two by Wickware, and won, 11-7. Wickware vowed that he would beat the Royal Giants the next day, and he did exactly that by throwing a six-hitter in a 9-2 Mohawk Giants victory.30

Controversy swirled around Wickware, on and off the field:

- A White team from Rutland, Vermont, recruited Wickware to pitch for them in an exhibition game against the Chicago Cubs on August 24, but the Cubs refused to take the field against him. Although it was widely reported that “color prejudice” was the reason, the New York Age said: “The Cubs have seen Wickware pitch in Chicago and know that he is effective in the box. … Chicago did not want to take a chance of having it advertised that [they were] defeated by a Negro.”31 Two days later, a White Northampton (Massachusetts) team forfeited a game rather than face Wickware pitching for a White Bellows Falls (Vermont) team.32

- An August game between the Mohawk Giants and McMahon’s Lincoln Giants was canceled by McMahon; “he would not play against Wickware, since Wickware had refused to play for him.”33

- Wickware’s wife, Dottie, was arrested in August for allegedly cutting the arm of May Bradley with a knife “during a quarrel between the women.”34 Bradley was the wife of Phil Bradley, the Mohawk Giants manager and center fielder.

Despite the distractions, Wickware pitched brilliantly. In Schenectady on September 14, he fanned 14 in a five-hit shutout of the Poughkeepsie Honey Bugs of the Class-D New York-New Jersey League. He and Phil Bradley slugged back-to-back home runs in the sixth inning; “so elated was one fan in the grand stand that he presented each player with a $5 bill.”35 Two weeks later, Wickware pitched shutouts in both games of a doubleheader versus the Cuban Giants of Buffalo.36 His verified record for the 1913 Mohawk Giants was 24-5 with nine shutouts.37 He was compared with the greatest White pitchers of the day, including Walter Johnson, Smoky Joe Wood, Christy Mathewson, and Grover Alexander.38

The most intriguing matchup of the season occurred on Sunday, October 5, in Schenectady. Wernecke had arranged a game between his Mohawk Giants and a barnstorming team known as Walter Johnson’s All-Americans. Johnson, coming off a phenomenal 36-7 season with the Washington Senators, would face Wickware in “a test of the best white pitcher against the best colored twirler.”39 The game was to start at 3:00 P.M. but was delayed 75 minutes when Wickware and eight teammates stormed off the field before the first pitch, declaring they would not play unless Wernecke paid the $921 he owed them. This precipitated a “near riot” by the overflow crowd, as people swarmed to the ticket booth to demand refunds.

According to the Schenectady Union-Star, “Wickware, in an ugly mood, used his tongue too freely as he strode about the crowd, swinging a bat dangerously near the spectators and muttering threats against Wernecke.” A local businessman rushed $500 to the scene as partial settlement, and the players were persuaded to return to the field. The game lasted 5½ innings before it was called because of darkness. Johnson struck out 11 and gave up only two hits, but the Mohawk Giants prevailed, 1-0. Wickware had defeated the great Walter Johnson.40

The showdown with Johnson was supposed to be the final game of the Mohawk Giants’ season, but after the game, Wickware and his teammates took the team uniforms and equipment and went to New York City, where they played as a team without Wernecke’s consent. Wickware struck out 13 and allowed five hits on October 12, but the Mohawk Giants were edged 2-1 in 10 innings by the Royal Giants.41

Back home in Coffeyville, Wickware’s father, Eldon, beamed with pride upon receiving a large poster advertising the game between the Mohawk Giants and Walter Johnson’s All-Americans. Eldon worked as a janitor at the Coffeyville Daily Journal. “Young Wickware is regarded as the world’s greatest colored pitcher,” reported the Journal.42

From January to March 1914, two teams of Negro stars played a series of games in Palm Beach, Florida, to entertain guests of the Royal Poinciana and Breakers hotels. Pitching for Royal Poinciana, Wickware was defeated three times by Cyclone Joe Williams and the Breakers.43

Wickware returned to Schenectady in April to pitch for the Mohawk Giants under new management. He dominated the teams he faced: 15 strikeouts in a three-hit shutout of the Amsterdams on May 31; 18 K’s in a four-hitter against a Schenectady team on June 14; and 17 strikeouts in a two-hit shutout of the Empires on July 9.44 The Mohawk Giants failed financially and disbanded in July.45 Rube Foster swept in and recruited Wickware to play for him.

Wickware was reunited with center fielder Pete Hill, shortstop John Henry Lloyd, and catcher Bruce Petway on the Chicago American Giants. On August 26 in Chicago, Wickware threw a no-hitter that was nearly a perfect game. George Shively of the Indianapolis ABCs led off the game by drawing a walk but was thrown out trying to steal second base. Wickware retired the next 26 batters in a row, as the American Giants nipped the ABCs, 1-0.46 Four days later Wickware delivered a three-hit shutout and fanned 12 in a 3-0 victory over the Royal Giants.47

Sportswriter Frank G. Menke described Wickware’s formidable curveball:

“Wickware has marvelous speed, a weird set of curves and wonderful control. And he has a trick that has made him feared among batters. He throws what seems to be a ‘bean-ball,’ but his control is so perfect that he never has hit a batter in the head. But when the batters see the ball, propelled with mighty force, come for their heads, they jump away — and the ball, taking its proper and well-timed curve, arches over the plate for a strike.”48

On June 22, 1915, Wickware tossed a two-hitter in the American Giants’ 6-1 victory over the Indianapolis ABCs. One of the hits was a single by 18-year-old Oscar Charleston, a future Hall of Famer.49 Wickware pitched both games of a doubleheader against the New York Lincoln Stars on August 10, winning the first game, 2-1, in 12 innings, and losing the second game, 1-0.50

Wickware’s nemesis in 1915 was a barnstorming team known as the Cuban Stars. Twenty-one-year-old Cristóbal Torriente, a future Hall of Famer, smacked two triples and a single off him in the Cubans’ 6-1 triumph over the American Giants on the Fourth of July.51 A week later Foster took Wickware out of the game after the Cubans scored five runs in the first inning.52 On August 15 Foster left him in as the Cubans pounded him for 10 runs on 17 hits.53

The American Giants played in the California Winter League in November and December 1915. Presumably divorced from the knife-wielding Dottie, Wickware married Elizabeth McCann in Chicago on May 18, 1915, and his new wife accompanied him on the trip to California.54 He posted a 6-1 record in the CWL, including a one-hit shutout on Thanksgiving Day against the San Diego Pantages, a team of top minor-league players, some with major-league experience.55

Wickware turned the tide against Cuban opponents in 1916. He and the American Giants defeated the Havana and Almendares teams in Cuba in March.56 Pitching for the ABCs in Indianapolis on May 8, he overcame the Cuban Stars, 5-4, in 10 innings.57 Back with the American Giants, he shut out the Cuban Stars in Chicago on July 7 and August 20.58 He also hurled shutouts against the St. Louis Giants on July 11 and the Lincoln Stars on August 13; the latter was a 12-inning gem that the Chicago Tribune called “one of the best games” of Wickware’s career.59

From April to July 1917, Wickware pitched for the Chicago Giants (not the American Giants) and Jewell’s ABCs of Indianapolis, but he returned to the American Giants in August 1917 and remained with the team until his induction into the Army a year later.60 He was stationed at Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois, at the tail end of World War I.61

Wickware bounced from team to team. In May 1919 he hurled a three-hit shutout with 15 strikeouts for the Detroit Stars against the Hayes Wheel team of Jackson, Michigan.62 He returned to the American Giants in July 1919, but in August he moved to the Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City.63 He pitched for the Norfolk All-Stars in 1920 before rejoining the American Giants in July of that year.64 From 1921 to 1923, Wickware pitched for the Chicago Giants, the Chicago Union Giants, and the Calgary Black Sox.65

Controversy was never far from Wickware. On June 11, 1924, he pitched the first inning of a game in Utica and “became dissatisfied with the ball being used and declined to continue in the box.”66 As a member of the Lincoln Giants in 1925, he was present when his teammate Dave Brown allegedly shot and killed a man on a Harlem street. Wickware was charged but later exonerated; Brown disappeared from the scene and was never located.67

Floyd “Jelly” Gardner, who was one of Wickware’s teammates on the 1920 American Giants, said Wickware “was a dissipator but a good pitcher.”68 But Wickware’s pitching skills declined rapidly as he entered his mid-30s and many felt alcohol was to blame. A 1926 editorial in the Pittsburgh Courier warned of “liquor, and its attendant evils,” and stated that “Frank Wickware liquored himself out of big time baseball.”69

At age 42, Wickware attempted a comeback as manager and pitcher of the Wickware Colored Giants of Bridgeport, Connecticut. On July 4, 1930, he threw a two-hitter but lost 1-0 to the Brooklyn Royal Giants.70

After his baseball career, Wickware settled in Schenectady, where he resided for the rest of his life. In 1939 he had a domestic dispute with his third wife, Sarah, and was charged with second-degree assault after he allegedly “struck his wife on the head with a six-foot stick,” opening “a deep gash at the base of her skull.”71 In 1948 Wickware received a four-month sentence for his role in the theft of boots from the Army depot where he was employed.72

Wickware died on November 2, 1967, in Schenectady, at the age of 79. His obituary in the Schenectady Gazette recalled the glorious day in 1913 when he beat Walter Johnson, 1-0, and noted that “only the majors’ color line … prevented him from becoming a big league star.”73

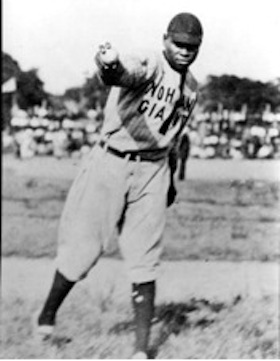

Photo credit

Frank Wickware, courtesy of the Frank Keetz Professional Baseball Collection.

Notes

1 Chicago Defender, August 30, 1930.

2 https://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/2006_Special_Committee_on_the_Negro_Leagues_Election.

3 https://wichitahof.com/kansas-baseball-hof-inductees.html.

4 1900 US Census; 1905 Kansas State Census; Coffeyville (Kansas) Daily Journal, May 16, 1910.

5 Coffeyville Daily Journal, April 7, 1919.

6 Muskogee (Oklahoma) Times-Democrat, August 1, 1907.

7 San Antonio Express, July 13 and August 10, 1908.

8 Chicago Tribune, April 25, 1910.

9 Chicago Tribune, June 6 and 27, 1910.

10 Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Daily Independent, September 20, 1910.

11 Robert Charles Cottrell, The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 59.

12 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 37; and The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (McFarland, 2002), 35-38.

13 Chicago Tribune, May 15 and 31; June 5 and 26; and July 6, 1911.

14 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 14 and March 6, 1912.

15 Chicago Tribune, May 20, 1912; New York Age, August 8, 1912.

16 New York Age, August 29, 1912.

17 New York Age, September 12, 1912.

18 New York Age, December 12, 1912.

19 Schenectady (New York) Gazette, May 21, 1913.

20 Schenectady Gazette, May 26, 1913.

21 Schenectady Gazette, June 9, 1913.

22 Schenectady Gazette, May 26 and August 14, 1913.

23 Schenectady Gazette, May 26, and July 7 and 14, 1913.

24 Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1911.

25 Schenectady Gazette, July 14, 1913.

26 New York Age, July 17, 1913.

27 New York Age, July 24, 1913.

28 Schenectady Gazette, July 21 and 22, 1913.

29 Schenectady Gazette, August 4, 1913.

30 Schenectady Gazette, August 13 and 14, 1913.

31 New York Age, August 28, 1913.

32 Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, August 27, 1913.

33 Schenectady Gazette, August 22, 1913.

34 Schenectady Gazette, August 26, 1913.

35 Schenectady Gazette, September 15, 1913.

36 Schenectady Gazette, September 29, 1913.

37 Frank M. Keetz, The Mohawk Colored Giants of Schenectady (Schenectady, New York: self-published, 1999), 7.

38 Schenectady Gazette, May 26 and September 5, 1913; Coffeyville Daily Journal, June 5, 1913; Allentown (Pennsylvania) Democrat, June 11, 1915.

39 Schenectady Gazette, October 1, 1913.

40 Keetz, 14–17.

41 Keetz, 17; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 13, 1913.

42 Coffeyville Daily Journal, November 22, 1913.

43 McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, 17-19.

44 Schenectady Gazette, June 1 and 15, 1914; Amsterdam (New York) Evening Recorder, July 10, 1914.

45 Keetz, 18-19.

46 Chicago Tribune, August 27, 1914.

47 Chicago Defender, September 5, 1914.

48 Allentown (Pennsylvania) Democrat, June 11, 1915.

49 Chicago Tribune, June 23, 1915.

50 Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1915.

51 Chicago Defender, July 10, 1915.

52 Chicago Tribune, July 12, 1915.

53 Chicago Defender, August 21, 1915.

54 Cook County, Illinois, Marriage Indexes, 1912-1942, at Ancestry.com; Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), 58.

55 McNeil, The California Winter League, 51-55; San Bernardino (California) News, November 26, 1915.

56 Chicago Defender, March 11 and 18, and April 8, 1916.

57 Indianapolis Star, May 9, 1916.

58 Chicago Tribune, July 8 and August 21, 1916.

59 Chicago Tribune, July 12 and August 14, 1916.

60 Chicago Tribune, April 23, May 21, and July 24 and 28, 1917, and March 9 and May 28, 1918; Chicago Defender, August 18, 1917, and July 20 and 27, 1918.

61 Chicago Defender, August 17 and 24, 1918.

62 Detroit Free Press, May 26, 1919.

63 Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1919; New York Age, August 9, 1919.

64 Chicago Defender, June 12 and July 17, 1920.

65 Chicago Defender, May 14 and July 30, 1921; Chicago Tribune, June 22, 1921, and September 10, 1923.

66 Schenectady Gazette, June 12, 1924.

67 James E. Overmyer, Black Ball and the Boardwalk: The Bacharach Giants of Atlantic City, 1916-1929 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2014), 132; Chicago Defender, May 23, 1925.

68 John B. Holway, Blackball Tales (Springfield, Virginia: Scorpio Books, 2008), 51.

69 Pittsburgh Courier, April 3, 1926.

70 Schenectady Gazette, July 22, 1930.

71 Schenectady Gazette, June 30, 1939.

72 Schenectady Gazette, March 24, 1948; Schenectady Herald-Journal, October 19, 1948.

73 Schenectady Gazette, November 6, 1967.

Full Name

Frank Ellis Wickware

Born

March 18, 1888 at Girard, KS (US)

Died

November 2, 1967 at Schenectady, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.