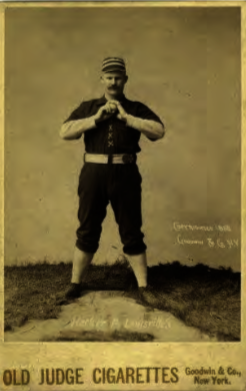

Guy Hecker

Guy Hecker has been regarded as the best combination of hitter and pitcher during the nineteenth century.1 In a major-league career that lasted from 1882 to 1890 he won 175 games and compiled a .282 batting average. But when one looks at his year-by-year record, two seasons stand out. Fittingly, one was as a hitter and one was as a pitcher.

Guy Hecker has been regarded as the best combination of hitter and pitcher during the nineteenth century.1 In a major-league career that lasted from 1882 to 1890 he won 175 games and compiled a .282 batting average. But when one looks at his year-by-year record, two seasons stand out. Fittingly, one was as a hitter and one was as a pitcher.

Guy Jackson Hecker was born April 3, 1856, to Thomas and Lucinda Hecker near Youngsville, Pennsylvania, in Warren County. Guy was the eldest of two brothers (Charles was a year younger), and his father worked as a laborer in Warren County. Guy was born three years prior to Edwin Drake drilling the first successful oil well in nearby Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. This event set off an oil boom in the area during the 1860s, and Thomas Hecker relocated his family up the Allegheny River to the prosperous town of Oil City in Venango County where he became the Superintendent of Streets for the borough of Venango.

Guy Hecker, who threw and batted right-handed, was a regular on the ball fields of Oil City and in 1877 landed a spot on his first professional team in Springfield, Ohio. He returned to Oil City after one season to marry and entered the business world while still playing in the amateur and semipro ranks in and around Oil City. In 1879 a young pitcher joined the team who would play a key role in getting Hecker to the majors. The pitcher was Tony Mullane, who won 284 games in his own major league career. Mullane became friendly with Hecker in his only season with Oil City, and when Tony joined the 1882 Louisville Eclipse in the newly formed American Association, he convinced the Louisville management to sign Hecker as a first-baseman and backup pitcher just before the start of the 1882 season.

In Hecker’s first big-league season he hit .276 in 78 games and split 12 decisions as a pitcher. The six-foot, 190-pounder split his major-league time as a pitcher (336 games) and first baseman (322 games) and spent 75 games in the outfield. The highpoint of his 1882 season came on September 19 when he threw the second no-hitter in American Association history, against the Alleghenys of Pittsburgh. He missed having the first no-hitter by a week when his teammate Mullane no-hit the Cincinnati club.

Mullane moved on to St. Louis in 1883 and Hecker became Louisville’s top pitcher. He posted a 28-23 record while pitching 469 innings. As a hitter he continued to hit in the .270s. In 1884 he exploded as a pitcher and began to develop as a major-league hitter. He raised his batting average to .297 and slugged at a .430 clip. But in the pitcher’s box Hecker was the dominant pitcher in the American Association. He set the American Association single-season records for wins (52), innings pitched (670 2/3 in 1884), and complete games (72). He completed the pitcher’s triple crown by leading the Association in ERA (1.80), and strikeouts (385). Only two other pitchers in major league history have won as many as 50 games in a season. A year after Hecker’s 50-win season, John Clarkson won 53. But Hecker’s real misfortune was that the all-time single-season wins record was set the same season Hecker won 52, as Charley Radbourn won 59 for Providence in the National League. Hecker’s 52-20 record in 1884 included a game against Washington in June in which he struck out the first seven batters he faced, and a one-hitter against St. Louis in August.

But records were not something players or fans thought much about in the 1800s, and Hecker opened the 1885 campaign ready to continue his mastery of the American Association. However, after a game on April 21 he complained of a sore arm. He tried to pitch though the arm trouble and had flashes of his old brilliance. There were various conjectures as to the cause of his troubles, including the enforcement of the rule requiring a pitcher to keep his delivery below his shoulder level. But no medical cause was ever announced, and Hecker compiled a 30-23 record in 480 innings pitched. His decline concerned the Louisville management enough that they purchased the contract of a young lefty from Chattanooga, Tom (Toad) Ramsey, late in the season. Hecker’s decline as a pitcher was matched in the batter’s box as his average dropped to .273 and his slugging average dropped nearly 100 points to .337.

Over the winter Hecker did two things. He allowed his arm to rest, and he opened the Hecker Supply Company in Louisville. During the 1885 season he had indicated his dissatisfaction with his salary, and it had been rumored that he was seeking his release from Louisville. It is probable that, instead of a higher salary, someone in the Louisville management agreed to help finance Hecker’s sporting goods company to keep him in Louisville. By January he was on the road hawking sporting goods across the South. The combination of resting his arm and starting a new business allowed him to miss much of the team’s preseason training routine. He never liked playing in cold weather and blamed the 1885 preseason for some of his arm troubles.

The 1886 season started well for Hecker as he was named team captain and won his Opening Day start with a three-hitter against Cincinnati. But within a week of that win he was diagnosed with an inflamed nerve in his right arm. Some on the Louisville team thought his pitching days were over. Through May he pitched about once a week and had compiled a 3-4 record. Most of the pitching load fell to Ramsey, who was 38-27 in 588 2/3 innings for the season. As Ramsey’s status with the team grew, he became more at odds with Hecker. Ramsey said that Hecker was jealous of Ramsey’s success and it would be good for the team if Hecker were released.2

An anti-Hecker clique grew, and Guy was soon replaced as team captain. But the dissension on the club continued. Hecker’s reputation as a gentleman and Ramsey’s as a hard drinker got prominent play in the local press. In the midst of this turmoil, Hecker found himself off to the best hitting season of his career. Hitting .417 in June, he raised his season’s average to .341.

But Hecker’s immediate problem was his arm. He tried corn plasters and massages. He tried rest and a lighter pitching load. In July he finally found a treatment that helped. Twice daily he would soak his arm in “electric-baths” at the Courier-Journal press room. He was so convinced of the benefits of this early “electronic-stimulation” treatment that he carried a galvanic battery on road trips. Hecker was back and he began pitching as well as he hit. Starting in July he won 11 straight games en route to a 26-23 pitching record.

During this period of rejuvenation, Hecker had the greatest hitting day any pitcher has ever experienced in the majors. In the second game of an August 15 doubleheader with Baltimore Hecker won the game as the starting pitcher while hitting three home runs and three singles with seven runs scored. His 15 total bases was a major-league record at the time, as was his three-homer game as a pitcher (matched by Jim Tobin in 1942). His seven runs scored remain the major-league single-game record by any player.

As his contribution in the pitcher’s box resumed, his batting was the best of his career. In July he hit .379. He upped that to .500 in August and found himself on top of the batting leaders list with a .378 average starting September. With the temperatures turning cooler Hecker’s average began to drop, and he closed the season with a .342 average. It took several weeks for the American Association office to announce the final averages and crown the season’s batting champ. When they did in November, standing atop the league was New York’s Dave Orr with a .346 average followed by Hecker and Bob Caruthers at .342 and Pete Browning and Tip O’Neill of St. Louis at .339. But many decades later, as statisticians researched and corrected baseball records for the publication of the Baseball Encyclopedia, the revised averages put Hecker’s .342 at the top of the list followed by Browning (.340), Orr (.338), Caruthers (.334), and O’Neill (.328). So Guy Hecker did not win the American Association batting title in 1886 but, as it turns out, he did post the highest batting average. Subsequent research has found that Hecker’s league-leading average in 1886 was actually .341. In 1886 Guy Hecker appeared in 49 games with 378 plate appearances. Modern readers may question Hecker’s eligibility for a batting championship but during the 19th century no league had any rules for minimum games, plate appearances, or at-bats for eligibility for the batting title.

In correspondence with David Nemec, author of the Great Nineteenth Century Baseball Encyclopedia and The Rules of Baseball, he states that “the best that can be said is that in every season the winner was at least a reasonable choice (if not always a correct one).” So someone in the league office assessed the final numbers and chose the champion based on whatever criteria seemed appropriate at the time. Nemec notes that in 1883 the American Association announced Tom Mansell as the batting champion “until media derision forced it to go with [Ed] Swartwood.” In the 1887 Reach’s Official American Association Base Ball Guide Hecker makes the list as Reach used a 20-game standard to be included in the publication. The 1887 Spalding Guide does not include Hecker as they used a 100-game standard.

After 1886 Hecker showed a rapid decline as both a hitter and a pitcher. Although his batting average in 1887 could be seen as a lusty .366, during that one season walks counted as hits. Without the 31 walks he hit .319 on a comparable basis with 1886.3 His pitching record fell to 18-12. There are two reasons given for his pitching decline. Having averaged over 500 innings pitched for four seasons could have ended his effectiveness. But 1887 also saw a shrinking of the pitcher’s box. Hecker’s pitching style included making a “hop, skip, and jump winding his arm beautifully about his head” to deliver a pitch.4 Having to change his pitching style to accommodate the smaller pitching area could also have contributed to his decline.

By 1889 the Louisville team that had been a first-division team in the early years of the American Association was now a perennial tail-ender. Undercapitalized and beset by seemingly annual ownership changes, the team sunk to a 27-111 record in 1889. Things took a particularly bad turn after the parsimonious Mordecai Davidson took over control of the club. Davidson squeezed what money he could out of the franchise, even naming himself manager for a brief period. When he instituted a series of fines for errors and poor play, the players began to revolt. After one payday where several players owed the club money due to fines and only one player received a full paycheck, they issued an ultimatum: either the fines were returned or they would refuse to play. Davidson refused and on June 14, 1889, Guy Hecker was one of six Louisville players to participate in the first major-league strike when they refused to take the field in Baltimore. The players returned the next day when the American Association agreed to mediate the dispute.

Most of the dispute was resolved with new ownership in August, but Guy Hecker’s Louisville run was about over. Pete Browning played his last game that season for Louisville in early September, and on September 17 Guy Hecker was released with a month to go in the season. The new management had decided to develop a younger team, and there was no place for the hero of 1884 and 1886.

Hecker left the American Association with his name high on several career pitching category lists. His Association record included 173 wins (third), 15 shutouts (eighth), 1078 strikeouts (fourth), 322 pitching appearances (second), and 137 losses (first).

In 1890 he replaced Ned Hanlon as the manager of the National League’s Pittsburgh club. But this was the year of the Players League revolt and Hecker presided over a ragtag bunch that lost 113 games. Over the next two seasons he was player-manager for Fort Wayne in the Northwestern League and Jacksonville in the Illinois-Indiana League. He returned to Oil City in 1893 to enter the oil business but kept active in baseball by managing the local team for several seasons. The locals called the independent team “Hecker’s Hitters.”

Guy Hecker died at the age of 82 on December 3, 1938, in Wooster, Ohio. He had settled in Wooster to operate a grocery store after leaving Oil City. At the time of his death the strong right arm that produced 52 major-league wins in 1884 was almost useless as a result of injuries suffered in an automobile accident in 1931. He was buried in Wooster Cemetery.

An updated version of this biography appears in “No-Hitters” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin. It also appears in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also relied on:

Nemec, David. The Beer and Whiskey League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994).

Thorn, John, Pete Palmer & Michael Gershman, eds., Total Baseball, 7th ed. (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001).

Louisville Commercial

Louisville Times

Oil City (Pennsylvania) Derrick

The Daily Record (Wooster, Ohio)

Notes

1 L. Robert Davids, ed. Great Hitting Pitchers Cooperstown: Society for American Baseball Research, 1979).

2 Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), May 25, 1886.

3 Depending on the standard used, one could find a batting average as high as .403: 149 hits and ealks / 407 PA = .366 BA; 149 hits and walks / 370 AB = .403 BA; 118 hits / 370 at-bats = .319 BA.

4 Courier-Journal, June 21, 1886.

Full Name

Guy Jackson Hecker

Born

April 3, 1856 at Youngsville, PA (USA)

Died

December 3, 1938 at Wooster, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.