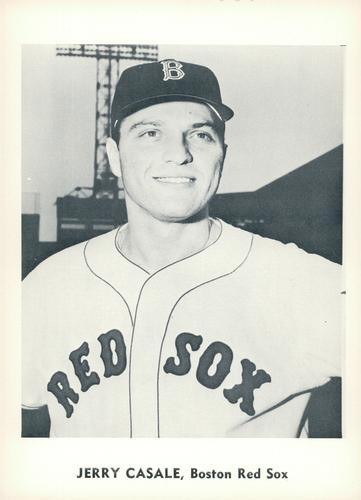

Jerry Casale

Brooklyn–born Gennaro Joseph Casale, better known as Jerry, played 11 seasons in professional baseball beginning in 1952 and concluding in 1963. During a five-year stretch, from 1958-1962, he pitched for three major-league teams, a hard-throwing right-hander and recorded his best season in 1959 as a 13-8 rookie with the Boston Red Sox. Casale was a good hitter, too—for a pitcher—and he hit some memorable home runs. In particular, one home run brought him a great deal of attention years after his playing days were over.

Brooklyn–born Gennaro Joseph Casale, better known as Jerry, played 11 seasons in professional baseball beginning in 1952 and concluding in 1963. During a five-year stretch, from 1958-1962, he pitched for three major-league teams, a hard-throwing right-hander and recorded his best season in 1959 as a 13-8 rookie with the Boston Red Sox. Casale was a good hitter, too—for a pitcher—and he hit some memorable home runs. In particular, one home run brought him a great deal of attention years after his playing days were over.

Casale’s life centered on the New York City region since his birth in Brooklyn on September 27, 1933. He spent his youth in Brooklyn, moved to Staten Island after being married, and then in his later years, lived in New Jersey. His parents, Gennaro and Maria Casale were born in Italy just outside of Naples, and immigrated to the United States. The family lived and owned a grocery store in Brooklyn. Young Gennaro was only about seven when his father passed away, at age 49, and his mother died eight years later. He was the youngest of six children. One of his brothers, Dominick, died as a young man the result of a tragic accident in the family butcher shop, and a sister died around the time Casale was born. Casale’s remaining brother, Lou, and his two sisters, Ann and Mary, managed the family after their mother’s death.1

Casale attended P.S. 77 elementary school and then Manual Training High School where he was graduated in 1951. He played basketball and baseball as a sophomore but was unable to play in his junior and senior years due to a strike in the public school system. Through a job with a candy factory he was able to play for the company’s semipro team in an industrial league. He also played ball through his church with a local CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) team, St. Francis Xavier, which won the 1950 CYO championship in Brooklyn.2

He was watched by numerous scouts and worked out with several teams before he was signed.3 Casale was a devoted Dodgers fan and he was thrilled when he was asked to throw some batting practice at Ebbets Field. The first batter he faced was future Hall of Famer Roy Campanella. The first pitch he threw was quite a bit inside, and it flattened Campanella. That was the end of his batting practice workout.4

Not long after graduation from high school in October 1951, Casale was signed by Red Sox scout Bots Nekola.5 Casale stood 6’1½” and weighed 200 pounds. He was labeled as “hard throwing,” “brawny, tough-talking,” and a “big fellow.”6

Casale began his professional career in 1952 for San Jose (California League, Class C); he went 14-13 with 211 strikeouts in 209 innings. His club made it to the playoffs but lost to Fresno, four games to two. He had control problems, and recalls one game early that season when he walked about 12 batters and struck out an equal number or more, and threw 200 pitches.7

In 1953 he moved up in the organization and played for three teams: Albany (New York) in the Class A Eastern League, Greensboro (North Carolina) in the Class B Carolina League, and Roanoke (Virginia) in the Class B Piedmont League. His overall record for those teams was 8-8 with a 5.50 ERA. Casale went back to Albany again in 1954 and had a good enough year to make the Eastern League all-star team. He was 14-8 on a team that finished in third place but went on the win the playoffs. He had an outstanding series, winning three games while losing none. He was the winning pitcher, in relief, in the clincher, and at the plate that game Casale had a double, a triple and three RBIs. Over that winter he played ball with Navojoa of Mexico’s Pacific Coast League.

He spent the 1955 season with Louisville (Kentucky) of the triple A American Association where he won 17 games against 11 losses, was the league’s strikeout leader with 186, and finished second with 2.96 ERA. Louisville finished in third place and made the playoffs but lost in six games to Omaha in the opening series. Again, Casale sparkled, winning the only two games he started, going the distance in each. During the offseason, he played winter ball in Puerto Rico.

In1956 spring training 1956, he was upbeat about his chances to make the Red Sox pitching staff given the past two years he had in the minors, and especially the 17 games he won at AAA. He felt he achieved what he had hoped for back in 1952: to be a good control pitcher.

Near the end of a solid spring training Casale was told that manager Mike Higgins wanted to see him. He excitedly went to see his manager expecting some good news. Instead, Higgins said they thought he needed more experience.8

An article in The Sporting News noted “…he was disappointed that he hadn’t been retained longer. This big fellow from Brooklyn throws bullets and the only thing he needs is a little more polish on his curve ball, experts say.”9 Casale harbored resentment toward manager Pinky Higgins and Red Sox GM Joe Cronin for restricting his progress to the major leagues.

An upset Casale decided he would go home and join the Army. On his way out of the clubhouse meeting with Higgins he met Cronin in the parking lot. Casale was angry and apparently Cronin was giving no ground. Cronin said even though he was being sent to the San Francisco Seals in the Pacific Coast League, they would be giving him big-league money. Then Cronin mentioned there was a large Italian community in San Francisco and he would be a good fit there.10, 11

The Red Sox had purchased the San Francisco territory for the 1956 season with the apparent intention of reserving the area for American League expansion. According to Dobbins12 there were public boasts the 1956 team would be “second to none.” However, confirming Casale’s conversation with Cronin there were a number of Italian ball players on the team as well. In addition to Casale, there were Ken Aspromonte, Bob DiPietro, Larry DiPippo, Frank Malzone, and Sal Taormina.

Now Casale felt he understood: the primary reason for his return to the minors was likely not due to his inexperience but, rather, a combination of having an Italian name and the ball club’s desire to generate attendance. In retrospect, perhaps this move was to the benefit of the Red Sox organization but being sent to San Francisco was more than a disappointment to Casale. The longer term upshot was that he missed out on a major league pension by 40-50 days. This resulted in Casale being left with Social Security as his only retirement income.

To Cronin’s credit, the Red Sox attempted to load the San Francisco club with top-notch talent for that 1956 season. Aspromonte, Casale, and Malzone were future major leaguers as were teammates Albie Pearson, Tommy Umphlett, Haywood Sullivan, and Marty Keough.13 Eddie Joost started the season as manager and was fired in midseason when Joe Gordon was brought on, and Casale ranked both as favorites and he noted both made you want to win.14

The Seals did not match their expectations and finished in sixth-place with a 77-88 record. Accounting for nearly 25% of the team’s wins, Casale was outstanding and went 19-11 with 16 complete games and an ERA of 4.10. He was also credited with hitting the longest home run at Seals Stadium, reputedly 551 feet. It went over the center-field scoreboard.15 As things turned out, Casale was a big star that year in San Francisco and, looking back, he said he “…loved it there.”16 Ironically, given the bout that spring with Cronin, the GM had written a letter to the draft board in 1956 requesting a temporary deferment for Casale.

He was recalled to Boston on September 1, 1956 but did not get into any major league games. He had finished three consecutive outstanding minor-league seasons running up an overall record of 55-30, a .647 record, including playoff games. For those three years his ERA was 3.44 and he had a ratio of 0.73 strikeouts per inning.

In December 1956 the draft board eventually caught up with Casale and he was inducted into the U. S. Army. He served with the 3rd Armored Division for nearly two years during 1957-58 mostly in Europe where he was able to play with the Army baseball team (in Denmark, Germany, and Holland).17 He felt his two years in the Army hurt his career. First, the caliber of teams he played against was more equivalent to high school and second, he came down with bursitis in his shoulder. The pain affected his ability to throw the fast ball and took away his curve ball, too.18

His first major-league game took place soon after his discharge from the Army on September 14, 1958. He had not picked up a baseball for a month or two but was promptly thrown into action…in both games of a double header against Detroit. Casale remembered he felt so strange because of the inactivity. But there he was, finally in the major leagues, and he recalled what a big thrill it was to look down at his uniform as he put it on for the first time. Best of all, he was pleasantly surprised he did as well as he did, holding the Tigers to no runs over three innings in those two games—striking out Harvey Kuenn twice, once in each game!19 He did not pitch again that season.

Following his nearly two-year layoff Casale decided to work himself back into shape by playing winter ball with Maracaibo in Venezuela. The experience paid off and at last Casale made the Red Sox out of spring training in 1959. For the season he went 13-8 with nine complete games and three shutouts. He was selected the Red Sox’ rookie of the year.

What a first start he had in the major leagues! In addition to a complete-game, 7-3 win, he hit a home run—450 feet according to The Sporting News20—off Washington’s Russ Kemmerer on April 15. In a 2004 interview Casale, looking at a mural of Fenway Park, proudly pointed toward the flagpole in left-center field where the ball left the park.21 He said it might have been the happiest day of his playing career, winning the game, hitting the home run, and striking out Roy Sievers of the Senators three times.22

He was off to a good start and it continued as Casale recorded three-hit shutouts on June 20 and July 27. The Sporting News was following his progress. On July 1, it featured Casale’s photograph and the caption “Jerry Does Job.” The ensuing article had the headline “Casale’s 5 Wins in a Row Chase Hub’s Hill Blues, Rookie Becomes Bosox’ Top Flinger.”23 The Red Sox had a six-game losing streak in late July but Jerry’s shutout on July 27 put a stop to that. Again he was the feature of an article in The Sporting News with his photo bearing the caption “Slump Stopper.” In the article it was noted “Rookie righthander Jerry Casale stopped the setback string from equaling the longest of the year—seven in a row. He pitched the finest game of his career in Cleveland on July 27, blanking the Indians on three singles.”24

He hit two more memorable home runs during the season. On July 22 Casale hit one in Chicago’s Comiskey Park off future Hall of Famer Early Wynn. On September 7, 1959 Jerry became part of baseball history when he, Don Buddin, and Pumpsie Green hit back-to-back-to-back home runs as the Red Sox beat the Yankees in Fenway Park with Casale picking up the 12-4 win. This homer was hit off Bob Turley and, while it was important in the win, it became even more “historic” for Casale in later years.

Playing alongside Ted Williams was a thrill for Casale. For the two years he played with the Red Sox his locker was next to Williams’. He said, “…Williams was a good guy. No b.s. with him, everything was black-white. What a hitter! The tougher the pitcher, the more he liked to face him…except for knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm.”25

Casale married a Brooklyn girl, Margaret (“Marge”) Mary Selleck, on November 1, 1959.26 He met her on a blind date and they dated more than three years. He and Marge have three children–Margaret (“DeeDee”), Patricia (“Pattie”), and James (“Jimmy”)–and five grandchildren.

In 1960, Casale suffered through a miserable year, finishing 2-9. He got off to a good start, winning on April 20 against the Yankees and Bob Turley in a complete game five-hitter. Six days later he won his second game, at that point half of all Red Sox victories. He remembered a tough 2-1 loss against the Baltimore Orioles on May 15 as a turning point. Steve Barber pitched a three-hitter, with Casale getting one of the hits. In looking back Casale said that his arm started “hurting like hell” but he “didn’t want to be taken out…I went to the bullpen when I should have gone to see a doctor.”27 During a six-game stretch in June and July Casale made six starts pitching in only 12 innings and allowing 25 runs. He ended the season in a relief role.

Unfortunately, his fortunes over the next two seasons did not improve. Casale was selected in the expansion draft by the Los Angeles Angels in December 1960. “At first we felt like all a bunch of rejects—which we were! We had some good players on the team but generally all were fringe major league players.”28

He is in the record book as the “first Angels losing pitcher” in a 3-0 loss to Boston in Fenway Park on April 15. He struck out eight in five 2/3 innings but had the misfortune to face rookie Carl Yastrzemski who tripled in one run and hit a sacrifice fly for another run and scored the third…these were Yaz’s first two major-league RBIs of an eventual 1,844.

Casale also hit the first home run by an Angels pitcher. It was on May 9, off Boston’s Ike Delock. He went 2-for-2 with a double to his credit, too, accounting for two Angels runs, and departed after five innings with a 5-4 lead. The Red Sox eventually tied it and while the Angels won it in the bottom of the ninth, Casale did not figure in the decision. Yastrzemski continued to make an impression on Casale hitting his first career home run in the fifth inning. After seven starts and 13 games for the Angels, Casale was traded to the Detroit Tigers on June 7. He left the Angels with a 1-5 record and an ERA of 6.54. but a batting average of .462. In a 2005 interview29 he said Los Angeles Wrigley Field, where the Angels played that first season, was a “bandbox” and a “terrible place to pitch.”

In July 1961 Casale was sold outright to Denver (American Association, Class AAA), where he posted a 4-1 record in the regular season then went 0-1 in the playoffs. He pitched well enough to win both games he started, but he was 0-1 and Denver lost Game Seven, a 1-0 five-hitter. He struck out eight and went 2-for-2 at the plate. He also had a home run in the series.

He came back in 1962 with the Tigers and pitched in 18 games, all but one in relief. But his arm still bothered him and he pitched in his last major-league game on July 22 against the Athletics. The Tigers assigned him to Denver once again. His record for that last, partial season in the majors was 1-2, with an ERA of 4.66. For Denver he started eight games, going the route twice, and finished with a mark of 4-2.

Casale’s last season of pro ball was in 1963 when his contract was assigned to Syracuse in December 1962 and then to Buffalo (International League, Class AAA) in April 1963, before being released in June. He finished this last season with Buffalo going 1-1 in 18 games, all but one was in relief.

His professional career ended nearly 12 years after his original signing in October 1951. He finished his career with an overall pitching record of 103-80, 17-24 in the majors and 86-56 in the minors. Two years in the Army, a sore arm, and fate that resulted in his one season in San Francisco caused Casale to miss out on a major league pension by 30 days. He said that the highest salary he made was $12,500.30

After his baseball career ended Casale went into the family’s butcher business with brother Lou. After 16 years, in 1977, he bought Pino’s, an “old-fashioned”31 Italian restaurant in Manhattan’s east side on 34th Street between Park and Lexington Avenues. Among baseball players and fans it was a well-known restaurant and was reputed to be a sanctuary for Red Sox fans and team personnel in town for a Boston-Yankees series.32 Pino’s was walking distance from New York’s Grand Hyatt where the Red Sox team would stay. Red Sox broadcaster Joe Castiglione has said that Pino’s was one of his favorites when in New York.33

Owning a restaurant was a natural fit for Casale who professed to enjoy meeting people and telling stories, and that’s what he did at Pino’s. He admitted the thing he missed most about baseball were the people in the baseball environment and running the restaurant, meeting people, filled this void.34

Casale displayed his allegiance to baseball, and his role playing it, by having a 20-foot-wide mural of Fenway Park painted on one of the restaurant’s walls, capturing the moment on September 7, 1959 when he connected for a home run against Bob Turley and the Yankees. The scene showed #19 Casale at bat and the scoreboard showing a 4-1 Red Sox lead just as he connected with the pitch for his home run. For those who wanted more information he also had a tape recording of the memorable moment. Ironically, his brother Lou was taping the game. “Lou, he don’t even know how to turn on the radio,” he was quoted telling a reporter in 2002, “but he got this right…(the) first pitch got by me before I realized what the catcher was doing, asking me, ‘How’s the family, Jerry? How’s the kids?’” The next pitch from Turley was the one Casale hit over the Green Monster that is recorded on the mural and on the tape. When he touched home plate he told Yogi Berra, the Yankees catcher who was chirping during his at-bat, “I’m not even married, Yogi.”35

Regarding Casale’s memorable home run, he was quoted as saying, “I’ve hit that home run 45,000 times by now.”36 “Turley keeps throwin’ it, and I keep whackin’ it.”37

Casale’s former Red Sox teammate, Ted Williams, enjoyed eating at Pino’s when he was in New York City. In David Halberstam’s book, The Teammates, a story was told of Williams detouring Dom DiMaggio and a few friends from a party at the fashionable “21” Club to Pino’s and that “he damn well was going to go there and eat at his old teammate’s place.”38 Halberstam noted that Pino’s was not in the Zagat restaurant survey but went on to say, if it were it would be described as follows: “This old-fashioned and unhip Italian restaurant, more Southern than Northern, has a warm and comfortable ambiance, and has the flavor of a ‘50s hangout. It serves hearty portions of traditional favorites and is popular with neighborhood regulars and sports stars, both present and past. Anti-smoking fanatics should stay away. The warm and outgoing owner once pitched for the Red Sox, and the walls are covered with mementoes of that time.”39

Following the tragedy of September 11, 2001, business at Pino’s declined and Casale and his wife, Marge, finally decided to close the restaurant in December 2003 after 27 years. When looking back, he admitted that he loved the restaurant business as much as playing baseball, and was proud to have been Pino’s chief cook for 10 of those years putting “his heart and soul into it.”40

By 2010 retired and living in New Jersey, Casale bragged about his children and grandchildren. Their oldest daughter, Patty, was an interior designer. Daughter number two, DeeDee, worked for a law firm. The Casales’ youngest child, son Jimmy, lived in Torrance, California, where he worked for Fox Television as a graphics artist.

There were baseball stories, too. Jimmy recalled being lucky enough to meet Ted Williams and his son John-Henry on several occasions in his family’s restaurant. “It was thrilling to say the least. Here was a baseball God sitting across from me…he and my Dad talking about the old days, John and myself not saying a word just listening. It was a surreal moment in my life. I’ll never forget it.”41

In 2007, at the age of 74, Casale had a stroke. As a result, he spent some time in the hospital and later in rehab. He felt it affected his speech. Perhaps it did a little, but to talk to him in his later years one would hardly notice any defect. More importantly. the stroke did not dampen his interest in telling stories, even ones where he could laugh at himself. He always loved to meet and greet people, he loved baseball, and he loved life.

On February 9, 2019, Jerry Casale died at the age of 85 in Paramus, New Jersey. After that stroke in 2007 he faced numerous ailments that included a broken hip, heart surgery, and prostate cancer.42 His wife Marge had passed away three years earlier, in March 2016. Casale left three children and five grandchildren. He was put to rest in Moravian Cemetery, Staten Island, New York.43 .

Notes

1 Jerry Casale, telephone interview, January 29, 2008.

2 “Scouting; 2-Star Restaurant,” New York Times, December 10, 1986.

3 Casale.

4 Ibid.

5 Jerry Casale, telephone interview, May 22, 2005. “Minor League Contract Card Collection,” Reel 40, four cards for Jerry Casale, entries from December 26, 1951 through August 2, 1963, from National Baseball Hall of Fame records, San Diego SABR Baseball Research Center, City of San Diego Public Library. Casale was far from being the only future major leaguer signed by Nekola. He had a quite a stable of signees for the Red Sox, having also signed Ken Aspromonte (1950), Carl Yastrzemski (1958), Rico Petrocelli (1962), Mike Nagy (1966), John Curtis (1968), and Ben Oglivie (1968).

6 Martin Jacobs and Jack McGuire, San Francisco Seals, (Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 104; Steve Buckley, Boston Red Sox, Where Have You Gone? (Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 136; and The Sporting News, April 4, 1956: 8.

7 Casale, January 29, 2008.

8 Ibid.

9 The Sporting News, April 4, 1956, 8.

10 Casale, January 29, 2008.

11 Maury Allen, “Baseball Players of the 1950s,” TheColumnists.com, February 2, 2004.

12 Dick Dobbins, The Grand Old League, An Oral History of the Old Pacific Coast League (Woodford Press, 1999), 59.

13 Jacobs, 104.

14 Casale, January 29, 2008.

15 Brent P. Kelley, The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957: Interviews with 25 Former Ballplayers (McFarland & Co., 2002), 172.

16 Casale, January 29, 2008.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 The Sporting News, April 22, 1959: 20.

21 Buckley, 136.

22 Ibid.

23 Hy Hurwitz, “Casale’s 5 Wins in a Row Chase Hub Hill Blues, Rookie Becomes Bosox’ Top Flinger; Harshman, Wills and Brewer Also Delivers,” The Sporting News: 17.

24 Hy Hurwitz, “Bosox Squirm Under Pinch of Tight Defeats,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1959: 21.

25 Casale, January 29, 2008.

26 The Sporting News Baseball Register, 1961: 182.

27 Casale, January 29, 2008.

28 Ibid.

29 Casale, May 22, 2005.

30 Casale, January 29, 2008.

31 David Koeppel, “Clashing With Pinstripes; Red Sox Fans Recoil in Yankees’ Backyard,” The New York Times, May 21, 2003.

32 Ibid.

33 Joe Castiglione, Broadcast Rites and Sites: I Saw It on the Radio with the Boston Red Sox (Taylor Trade Publications, 2004), 172.

34 Buckley, 138.

35 Vic Ziegel, “Career Thrown a Curve, Brooklyn’s Jerry Casale could pitch, but had bad timing,” New York Daily News, June 24, 2002.

36 Koeppel.

37 Ziegel.

38 David Halberstam, The Teammates, A Portrait of a Friendship (Hyperion, 2003), 23.

39 Ibid., 24.

40 Casale, January 29, 2008 interview. At one point, in 1986, Casale had sold Pino’s to another family member. At the time he entered into a partnership with three others to open up a new restaurant in Manhattan called “17 Marie Street.” The partners included former ballplayers Ron Darling and Art Shamsky, and Tony Ferrara, a batting practice pitcher for the Mets and Yankees at that time. The restaurant did not succeed and within a short period of time Casale found himself back with Pino’s.

41 Jimmy Casale, email, January 29, 2008.

42 Jimmy Casale, email, February 10, 2019.

Full Name

Gennaro Joseph Casale

Born

September 27, 1933 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

February 9, 2019 at Paramus, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.