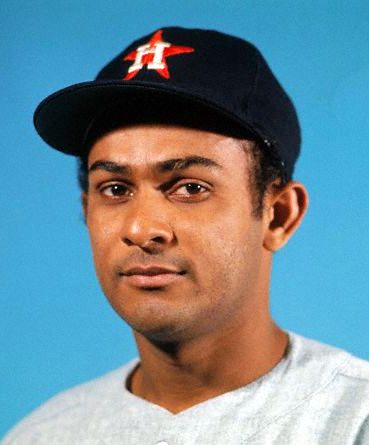

Jesús Alou

He enjoyed a 15-year career in the major leagues and today is well into his sixth decade working in baseball, but Jesús Alou is destined to be remembered as the third brother in an extraordinary baseball family. He might have accomplished less as a player than his two All-Star siblings, but those comparisons are unfair. Jesús had a fine career in his own right as part of the first great wave of Dominican players that came to the major leagues in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Jesús Alou was the 13th Dominican in the majors, though just third in his own family.

José Rojas and Virginia Alou raised six children (Felipe, María, Mateo, Jesús, Juan and Virginia) in their small home in Bajos de Haina, San Cristóbal, near Santo Domingo on the southern coast of the Dominican Republic. Rojas, a carpenter and blacksmith who built their home and others in the neighborhood, also fathered two children with a previous wife who had passed away. Though José was black and Virginia white, this was not unusual in the Dominican and the children knew little racism in their homeland—they were Dominicans. The family was poor, like most people they knew. “We all helped [our father] in the shop,” recalled Jesús, “but no money was coming in because everyone was poor around there. I was happy, though, just thinking about where my next meal might come from.”1

Jesús María Rojas Alou was born on March 24, 1942. In keeping with the Latino custom, each parent contributed half of his double surname, but he is known in everyday life as Jesús Rojas in his homeland. While Felipe was playing in the US minor leagues, a team official mistakenly began identifying him as Felipe Alou, and he did not feel empowered to correct the error. When Mateo and Jesús followed him to the States, they used the Alou surname in order to associate with Felipe.

If this were not enough, many American writers and broadcasters were uncomfortable with his first name (properly pronounced “hay-SOOS”). Although there have been more than a dozen players named Jesús in the major leagues, Jesús Alou was the first, and is still the most prominent. Before his first season with the Giants, a San Francisco writer asked local religious leaders about the situation, and they all agreed that he needed a nickname, that reading “Jesus Saves Giants” in the morning paper would not do. The paper asked readers to write in with their suggestions, which many did.2 His Latino teammates often called him Chuchito, but the writers often called him Jay. “What,” the subject asked in 1965, “is wrong with my real name, Jesús? It is a common name in Latin America like Joe or Tom or Frank in the United States. My parents named me Jesús and I am proud of my name.”3 Thankfully, by the end of his career, everyone, even the writers, called him Jesús.

When Jesús was born, Felipe was nearly seven years old, while Mateo (later known mainly as “Matty” in the U.S.) was three. Unlike his older brothers, Jesús came to baseball slowly and somewhat reluctantly. “I wouldn’t even go and watch Felipe and Mateo play on the lots around our home,” he recalled. “I went fishing.”4 When he did play, the brothers used bats that they made on their father’s lathe.5 In fact, it was mainly his brothers’ success that led Frank (Chick) Genovese, who managed the other Rojas brothers on Leones del Escogido in the Dominican Winter League, to pressure Jesús to give baseball a try. Genovese’s cause was joined by Horacio Martínez, a former Negro Leaguer who worked as a bird dog for New York Giants scout Alejandro Pómpez and helped run the Escogido team. In late 1958 the 16-year-old Jesús signed to be the team’s batting practice pitcher.

At about the same time, Genovese signed Jesús for the San Francisco Giants organization , as he had done a few years earlier with Felipe and Mateo. The man who would now be known as Jesús Alou had very little organized baseball experience and the Giants’ optimism was largely based on the talents of Felipe, who had made the major leagues, and Mateo, who had hit .321 for St. Cloud the previous year. Jesús was assigned to Hastings, Nebraska, which had a team in the short-season Nebraska State League. Alou pitched just two games, allowing 11 runs in five innings, though he did manage to finish 2-for-3 as a batter. “I don’t win. I don’t lose,” Alou recalled of his summer in Nebraska. “I don’t do much of anything except brood.”6

, as he had done a few years earlier with Felipe and Mateo. The man who would now be known as Jesús Alou had very little organized baseball experience and the Giants’ optimism was largely based on the talents of Felipe, who had made the major leagues, and Mateo, who had hit .321 for St. Cloud the previous year. Jesús was assigned to Hastings, Nebraska, which had a team in the short-season Nebraska State League. Alou pitched just two games, allowing 11 runs in five innings, though he did manage to finish 2-for-3 as a batter. “I don’t win. I don’t lose,” Alou recalled of his summer in Nebraska. “I don’t do much of anything except brood.”6

The next winter Alou hurt his arm throwing batting practice for Escogido, and thought his reluctant baseball experiment might have ended before he turned 18. He reported to the minor league camp for the Giants in 1960, and was assigned to Artesia (New Mexico), a Class-D affiliate. Manager George Genovese, the brother of Chick, wanted Alou to give up pitching and play the outfield, like his brothers. Again Alou balked, suggesting instead that he just go home. He finally agreed, and played the entire year in center field. His hitting was great (.352 with 11 home runs and 33 doubles), though his outfield play was a bit raw due to his sore arm. “It was a tougher year on Gil Garrido, our shortstop, than it was for me,” Alou remembered. “My arm was so bad that every time a ball was hit out to me Garrido had to race almost to my side to take the cutoff throw.”7

Tough year or not, Garrido, a future major leaguer from Panama, hit .362 to win the batting title, while Alou led the league with 188 hits. Both were named to the league’s postseason All-Star team. After the Artesia season was over, the 18-year-old Alou played a few games with Eugene (Oregon) of the Northwest League, where he hit .350 in 20 at-bats.

Alou’s remaining years in the minor leagues were equally successful. Spending the 1961 season back in Eugene, he hit .336, led the league in hits, and was named a postseason All-Star. The next year in El Paso (Texas League), the 20-year-old Alou hit .346. Finally reaching the top rung of the ladder (Triple-A Tacoma) in 1963, Alou hit .324 with 210 hits (a total that broke Matty’s former Tacoma all-time record). He was an All-Star at every level, and had done everything he could to earn a spot with the Giants. On September 10, 1963, he finally made it, pinch-hitting against the New York Mets, grounding out against Carlton Willey to lead off the eighth. Willey then retired Mateo and Felipe for a 1-2-3 inning. The three brothers also played the outfield together briefly five days later. During his call-up, Jesús hit .250 in 24 at-bats.

As his major-league career was starting, many people believed that he would surpass both his brothers as a player. Among the believers were his brothers. “Jesús represents our family now,” said Felipe. “He has the right approach to baseball. Matty and I are, how you say it? We’re satisfied. We’re in the majors doing the best we can. But Jesús, he is a restless man. If he can’t be supreme, he doesn’t want to be at all. He has to be the greatest.”8 As evidence, people could point to his performance with Escogido, where the three brothers had formed the outfield over several winters. As early as 1961, Alejandro Pómpez had said, “Jesús Alou hits the curve ball twice as good as most kids who have been around much longer. The day will come when he’ll outshine both Felipe and Matty.”9

Jesús had already outgrown both of his brothers, reaching 6’2” and 190 pounds by the time of his debut. George Genovese, who had managed Jesús a few times in the minors, was optimistic. “He has live hands and a fast bat and he attacks the ball with great aggressiveness,” he said. “When he puts on another 15 pounds, he will have more power than Felipe.”10 Added manager Al Dark, “We think young Alou is one of the finest players our farm system has developed in recent years.”11

Thoughts of an all-Alou outfield in San Francisco were unrealistic, however. The team already had star performers in center field (Willie Mays), left field (Willie McCovey), and first base (Orlando Cepeda). Felipe Alou had established himself as a good player in right field, while Matty Alou was behind Harvey Kuenn among the extra outfielders. After the season, the Giants partly dealt with the logjam by trading Felipe to the Braves. They announced that Jesús, and not Matty, would get first crack at the right-field job.

The biggest flaw in Jesús’s game, then and later, was his inability to take a walk. Even in the 1960s this was remarked upon, though more as a curiosity than a flaw. In 1963 baseball increased the dimension of the strike zone from the bottom of the knee to the top of the shoulders, which did not affect Jesús at all. As a Tacoma writer remarked, “Jesús has a personal strike zone which far exceeds anything considered by rulesmakers.”12 Teammate Juan Marichal remembered, “One time. . . a pitch [came in] about level with Jesus’s head. Jesus swung at it and hit a home run to right field. He was that type of hitter.”13 But the Giants were ready to live with his approach. “He swings at quite a few bad balls,” admitted farm director Carl Hubbell, “but I call him one of those ‘they shall not pass’ hitters. If he can reach a ball, he’ll swing.”14

Alou played fairly regularly in 1964, hitting .274 but with little power (three home runs) or plate discipline (13 walks). On July 10 he enjoyed the game of his career, when he went 6-for-6 with a home run in a Giant victory in Chicago’s Wrigley Field. His season ended abruptly on September 4 when he was spiked at second base by New York’s Ron Hunt, resulting in 91 stitches in his foot, ankle, and calf. He came back the next year to play 143 games, batting .298 with nine home runs. At a time when the league hit just .249, his average was impressive, but his 13 walks gave him only a .317 on-base percentage, just over the league average. With Alou’s skill set, he was going to have to hit .320 to be a star, and most observers believed that he would. He turned just 23 in 1965.

Alou reported in 1966 determined to improve his batting eye. “I know pitchers are getting me to swing at bad pitches,” he admitted. “I try to cut it down this year. Sometimes maybe I forget, but I am going to cut it way down, I think.”15 Instead, he took a step back, and when he was hitting just .232 with two walks in nearly full-time play on June 13, he was optioned to Phoenix for two weeks, ostensibly because of a sore arm. He hit better upon his return, and got his average up to .259. It was a big year for the other Alou brothers: Matty, traded to the Pirates the previous winter, hit .342 to capture the league batting title; and Felipe, playing for the Braves, finished second at .327 while also clubbing 31 home runs. The talk of Jesús being the best of the Alou brothers had quieted down.

After the 1966 season, Jesús allowed that he wanted to be traded, reasoning that his brothers had found success after leaving San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, whose cold winds created difficulties for both hitters and outfielders. During the winter meetings, the Giants reportedly talked to other clubs about Alou, but held on to him.

In 1967 Alou played more or less full-time, and returned to his 1965 levels of hitting: .292 in 510 at bats, though again with little power (five home runs) and few walks (14). Oddly, the Giants used Alou as their primary leadoff hitter. As manager Herman Franks explained, Alou’s swinging and missing at so many bad pitches made him a bad hit-and-run guy, so he didn’t like him up with men on base. “So,” said Franks, “the leadoff position is where he can do the least harm and definitely the most good.”16 Alou hit .308 as the leadoff batter, and hit .337 when leading off innings.

The 26-year-old Alou played left and right fields for the Giants in 1968, starting 97 games and playing parts of 23 others. He regressed a bit from his 1967 comeback, hitting just .263 with no home runs and nine walks in 436 plate appearances. This turned out to be his final go-round with the Giants, as on October 15 Alou was selected by the Montreal Expos in an expansion draft to stock the two new National League teams.

Montreal reportedly turned down several trade offers for Alou, including one from the Astros for Mike Cuellar. After several weeks of speculation, on January 22 the Expos dealt Alou and Donn Clendenon to the Astros for outfielder Rusty Staub. Six weeks later Clendenon announced that he would retire rather than report to Houston, nullifying the trade for a few weeks. Eventually the Expos substituted two pitchers and some money to get the deal done. Houston manager Harry Walker coveted Alou, as he wanted more speed in the outfield. Walker had long fancied himself a hitting guru, and his biggest success story had been Matty Alou, who became a consistent .330 hitter after joining up with Walker in Pittsburgh in 1966.

Jesús Alou began the 1969 season as the Astros’ right fielder and leadoff hitter, and stroked three hits in his first game. He then went into a long slump that lasted most of the year, though his season was partly saved by a .328 final month. On June 10, while playing left field, Alou was involved in a brutal collision with shortstop Héctor Torres. His teammate’s forehead hit Alou’s face and caused him to swallow his tongue. Pirates trainer Tony Bartirome may have saved the unconscious Alou’s life when he pried open his mouth, inserted a rubber tube and breathed into it, which opened his air passage enough so that Alou could resume breathing. Alou and Torres were each carried off the field and rushed to the hospital—both players suffered concussions while Alou fractured his jaw. He missed six weeks of action. For the season, he hit just .248.

Alou was not a regular to start the 1970 season, but his consistent hitting eventually got him an everyday role. He ended up hitting .306 in 115 games, with a career-high 21 walks. “To me, hitting .300 is not all that big an issue,” he said late in the year. “What is important for me as the leadoff hitter is to get on base. I think I’ve been good, actually, ever since I came out of the hospital last year.”17 Once again he excelled as a leadoff hitter—he hit .392 leading off games, and hit .328 when leading off an inning. In 1971, he started even hotter, hitting over .350 into June, before slowly dropping off. A bad September left him at .279 for the season.

Through it all, baseball people liked having Jesús Alou around. Jim Bouton, an Astros teammate in 1969 and 1970, described him in his second book, I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally. “We called him J. or Jesus, never hay-soos. . . J. is one of the most delicate, sensitive, nicest men I have ever met. He’d walk a mile out of his way to drop a coin in some beggar’s cup.” Bouton then went on to describe how Alou’s sensitivity made him a comic foil for practical joker Doug Rader’s most disgusting antics.

“Alou is popular with his teammates because of his inherent good nature and philosophical way of looking at things,” said another writer in 1971. “And Alou is interesting to watch during a game.” He drew much comment throughout his career for all his mannerisms in the batter’s box—he held the bat vertical directly behind his right ear, then repeatedly rotated his neck. “People write letters asking why I jerk my neck,” Alou said. “I can’t answer except to say it’s not a back problem. It’s just a mental problem.”18 Early in his career Dodger pitcher Don Drysdale thought Alou might be trying to steal the catcher’s signs, and subsequently knocked Alou down with a pitch.19 Yet the habit remained.

Alou also had a very self-deprecating sense of humor. Late in his career he failed to reach a fly ball in the outfield, and observed, “Ten years ago, I would have overrun it.”20 When reminiscing about his years in the game, he would often recall moments when he forgot how many outs there were or the time he overran a base.21 Despite his relatively modest accomplishments, he stayed in the game a long time because his managers and teammates liked him so much. He was quiet and dignified, and often could be seen reading a Bible at his locker.

As Jimmy Wynn recounted in his autobiography, though, Harry Walker’s inveterate tinkering with hitters and their approach at the plate managed to infuriate even “The J. Alou” — as Jesús jocularly referred to himself. “The Hat” went so far as to break Alou’s bat in order to make sure that his player used a Harry Walker model. Another clubhouse incident a few days later finally set Alou off, and Wynn later wrote, “We are laughing in shock over the discovery that he is capable of anger at this level.”22

With the emergence of Bob Watson and Cesar Cedeño, and the presence of Wynn, Alou no longer had a regular job after the 1971 season. He hit .312 in 1972 as a reserve outfielder and pinch-hitter, but just .236 in the same role the following season. On July 31, 1973, his contract was sold to the Oakland Athletics.

The A’s had won the World Series in 1972 and would repeat the next two seasons. Alou played 20 games over the last two months of the 1973 season, mainly in left field, and hit .306. When regular center fielder Bill North sprained his ankle that September, it opened the door for Jesús to play in the postseason. He hit 2-for-6 in the ALCS, but just 3-for-19 in the World Series. The next year he stayed with the A’s the entire year and got 232 plate appearances, mainly as a designated hitter, hitting .262. He hit just twice in the postseason, including a pinch single in the first game of the ALCS. Matty Alou had helped win a World Series for the A’s in 1972, and now Jesús had won back-to-back with the same club.

The next spring Alou was released. “Maybe I’m overrating myself,” he said. “I think this team needs a guy who does the type of job I can do.”23 He was soon picked up by the New York Mets. “I was offered more money to play with my brother, Matty, in Japan,” Alou said, “but I prefer to play in the United States.” Alou served as a reserve outfielder and pinch-hitter, hitting .265 in 108 plate appearances.

In March 1976 he was released again, and this time he headed back to the Dominican, where he remained for two years. Besides playing winter ball in his homeland, he and a friend tried to start a business. “We were going to start a watch-assembly plant in the Dominican Republic,” he recalled. “We would buy the parts in other countries and assemble the watches there. But the government down there didn’t like the idea.”24 After two years away, Alou returned to the major leagues with the Astros in 1978, and hit .324 in a reserve role. When he returned the next year, the 37-year-old took on the added role of batting coach. He hit .256 this time around in just 43 at bats, though his relatively high walk total (6) gave him a respectable .349 on base percentage.

After the 1979 season Alou drew his release, and his major-league career was over. He finished with a respectable .280 batting average, but his walk rate of just 3 per 100 plate appearances was the lowest in the 20th century for someone who played 1,000 games. He played parts of 15 seasons in the majors, and won two World Series. In the Dominican, he starred for many years for Escogido with his two brothers. He was Rookie of the Year in 1960-61. His lifetime stats at home were .302 with 20 homers and 339 RBIs in 20 seasons (12 for Escogido and 8 for archrival Licey). He played in five Caribbean Series (1973, 1974, 1977, 1978, and 1980), hitting .351 with two homers and 13 RBIs. One of his highlights in a Dominican uniform came during the 1973 edition in Caracas, Venezuela, when he was 12 for 24 (.500) as Licey won the tournament.25

Jesús Alou married Angela Hanley in the late 1960s, and the couple raised five children—Angela, Jesús Jr., María de Jesús, Claudia, and Jeimy—in the Dominican Republic. After his playing career ended, Alou moved back home and remained there, still fishing and swimming in the nearby waters in the summer. He lived not far from where he grew up, and not far from the homes of his brothers and sisters. “I guess we look much richer to the people here than we really are,” he once observed.

Although he did some managing in the Dominican winter league, Alou turned to scouting when his pitching coach with Escogido, Bob Gebhard, became an executive with the Montreal Expos. Jesús said, “I imagine he saw me working with kids. Even when I was a player, I liked to work with kids.” In typical form, he added, “I have very high blood pressure. I don’t think I can stand managing.”26

He continued to work for American baseball, moving from the Expos to the Marlins. In 2002, he became the Dominican scouting director for the Boston Red Sox. He also served as director of the team’s Dominican Summer League operations, much the same role as he had held with the Marlins’ Dominican academy.

Jesús came back to San Francisco in 2003 for Opening Day, joined by his two brothers, one of whom (Felipe) was now managing the Giants. They had all accomplished so much in the game, forty years after playing in the same outfield. “I have never dreamed anything in baseball,” Jesús said. “Everything has been a surprise. Every day is a new surprise. Felipe being manager in San Francisco makes me proud. It’s another surprise.”27

Dominicans have come to play a huge role in American baseball, following in the giant footsteps of Felipe, Mateo, and Jesús Alou. Late in his career, Jesús was asked to compare the skills of the three Alous. “Felipe is a very tough guy in baseball,” he said, “tougher than all of us. Matty was smaller and had to take more advantage of his ability, the guy who does more thinking. Me, I wasn’t as tough as Felipe or as thinking as Matty. One thing we had in common: we didn’t like to strike out too much, maybe because we used to play with rubber balls in our backyard. As long as a guy didn’t strike out, he could keep batting, and we all liked to bat.”28 The brothers played over 5,000 major-league games between them.

Jesus died on March 10, 2023 in his beloved Santo Domingo. He spent 60 years in the game as a player, and was still working for the Red Sox at the time of his passing. He was a vital part of a great baseball family, and his legacy will live on.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rory Costello for his editing and for adding a few additional stories to the article. Thanks also to Gabriel Schechter, Rod Nelson, and Matías Alou.

Notes

1 Joseph Durso, “We Band of Brothers,” The New York Times, August 14, 1975.

2 Prescott Sullivan, “Wanted—Name for New Right Fielder!” San Francisco Examiner, March 6, 1964.

3 Bob Stevens, “Jesús Alou Could Be the Best in Family,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1965, 7.

4 Bob Stevens, “The Little Alou,” Sport, September 1965, 81.

5 Jack McDonald, “No. 3 Alou May Gain No. 1 Spot,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1963, 10.

6 Stevens, “The Little Alou,” 81.

7 Stevens, “The Little Alou,” 81.

8 Stevens, “The Little Alou,” 80.

9 Jack McDonald, “Giants Phenoms Train in Lap of Luxury,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1961, 9.

10 McDonald, “No. 3 Alou May Gain No. 1 Spot,” 10.

11 Jack McDonald, “Giants,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1964, 24.

12 Ed Honeywell, “Jesús Alou Gives Up Passes to Hit Away,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1963, 33.

13 Juan Marichal with Lew Freedman, Juan Marichal: My Journey from the Dominican Republic to Cooperstown, Minneapolis, Minnesota: MVP Books, 2011, 114. Marichal’s memory was fuzzy about the details. He recalled it as being in San Francisco against Jim Bunning of the Phillies, but SABR’s Home Run Log shows no such record.

14 Jack McDonald, “Giants Paint Pennant Picture With Jesús Alou and Jim Ray Hart.” The Sporting News, January 4, 1964, 10.

15 Jack McDonald, “Those Bad Pitches Look Too Juicy for Jesús Alou to Resist,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1966, 17.

16 Bob Stevens, “Alou a Goliath in Giant Leadoff Spot,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1967, 16T.

17 John Wilson, “Jay Alou Giving Brothers Lesson in Swatting Art,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1970, 17.

18 John Wilson, “A Sizzling Bat Pushes Alou Into Astros’ Lineup,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1971 24.

19 Stevens, “The Little Alou,” 80.

20 Gordon Verrell, “Dodgers Tap Rookie Wall to Add Bullpen Depth,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1976, 28.

21 Mike Mandel, SF Giants. An Oral History (Santa Cruz: self-published, 1979), 149.

22 Jimmy Wynn and Bill McCurdy, Toy Cannon: The Autobiography of Baseball’s Jimmy Wynn, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2010, 121-122.

23 Ron Bergman, “Happy Charlie Does Jig Over Hippity-Hoppy,” The Sporting News, April 19. 1975, 5.

24 Harry Shattuck, “Bat Artist Alou Doubles as Astro bat tutor,” The Sporting News, March 17, 1979, 51.

25 Gustavo Rodríguzez, “Jesús Alou: Ganó la triple corona en SC en 1973,” Hoy (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, January 26, 2012.

26 Gordon Edes, “Alou Acts as Scout, Dreams as a Player,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, February 8, 1994.

27 Associated Press, “Alou reunion takes place in San Francisco,” Albany Times-Union, April 8, 2003.

28 Joseph Durso, “We Band of Brothers,” The New York Times, August 14, 1975.

Full Name

Jesus Maria Rojas Alou

Born

March 24, 1942 at Bajos de Haina, San Cristobal (Dominican Republic)

Died

March 10, 2023 at Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional (Dominican Republic)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.