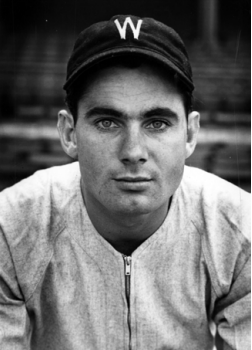

Jimmy Bloodworth

In June 1950 Jimmy Bloodworth, one of the oldest players on the Philadelphia Phillies youthful roster, quipped, “It took me 34 years to become a Whiz Kid.”1 In truth, Jimmy was soon to turn only 33 but that didn’t prevent him from another of the many wisecracks that endeared him to fans and teammates alike. But Bloodworth was capable of more than one-liners. In 1942 he was cast as Detroit’s second-base replacement for retiring future Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer. Military service in World War II derailed these plans and Bloodworth’s 11-year major-league career garnered less than 3,800 plate appearances. Possessing little speed but a powerful bat, Bloodworth originally seemed on a much brighter path.

In June 1950 Jimmy Bloodworth, one of the oldest players on the Philadelphia Phillies youthful roster, quipped, “It took me 34 years to become a Whiz Kid.”1 In truth, Jimmy was soon to turn only 33 but that didn’t prevent him from another of the many wisecracks that endeared him to fans and teammates alike. But Bloodworth was capable of more than one-liners. In 1942 he was cast as Detroit’s second-base replacement for retiring future Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer. Military service in World War II derailed these plans and Bloodworth’s 11-year major-league career garnered less than 3,800 plate appearances. Possessing little speed but a powerful bat, Bloodworth originally seemed on a much brighter path.

James Henry Bloodworth was born on July 26, 1917, in Tallahassee, Florida, but spent his life 80 miles southwest in the coastal city of Apalachicola. The third of four children (and the second son), he was descended from a long line of Bloodworths dating to the seventeenth century in one of America’s earliest settlements — the extinct locality of Nansemond, now a part of Suffolk County, Virginia. On his mother’s side Jimmy was the great-grandson of Italian immigrants who had arrived in the late nineteenth century. This rich heritage was accompanied by a strong “athletic gene” that extended to Jimmy, his brothers, sons, and nephew — the latter, Ronald Bloodworth, joined Jimmy among baseball’s professional ranks in the 1950s. Interest in Jimmy’s older brother Benjamin (known as “Francis”) initiated Bloodworth’s entry into Organized Baseball.

In 1934 a Washington Senators scout — believed to be former lefty hurler Joe Engel – spied Francis among the town teams in Florida’s panhandle and extended a contract. The father of one with another on the way, Francis felt the offer was insufficient to sustain his growing family and declined, but pointed the scout to his younger brother. “Francis was a better player than me and everyone in Apalachicola knew that,” Jimmy quipped years later. “And he was lucky. He got to stay home and play baseball but I had to go all the way to Washington, D.C., to find someone to let me play.”2 In 1935, shortly before his graduation from Chapman High School, Jimmy signed with the Senators. He traveled the short distance to Panama City, Florida, to pursue his dreams.

The Panama City Pilots represented the lowest level (Class D) of Organized Baseball. At 17, Bloodworth was one of the youngest players in the Georgia-Florida League as he manned the outfield for 55 games. He was the Pilots’ only nonpitcher to advance to the major leagues, but more immediately, his .305 pace in 200 at-bats prompted a late-season promotion to Class-A Chattanooga, where went 3-for-11 with a home run.

Bloodworth’s continued progress over the next two years eventually earned a call to the majors. On September 14, 1937, he played his first big-league game, in Washington’s Griffith Stadium against the Detroit Tigers. He went hitless in his first two games, then connected for a single against the St. Louis Browns on September 18. After “showing signs of getting over stage-fright,”3 Bloodworth produced at a .294 pace with eight RBIs in his next 34 at-bats and positioned himself for a berth on the 1938 Senators team. Bloodworth’s competition would have been steep. The incumbent second baseman, Buddy Myer, was concluding his second All Star campaign. But Bloodworth did not get the opportunity to compete for any position at all due to the high-level machinations of the Washington franchise.

The owner of the Senators, Clark Griffith, owned the minor-league affiliate Chattanooga Lookouts as well. In 1937 he had appointed his 25-year-old nephew, Calvin Griffith, as manager of the moribund club. As losses mounted and attendance waned, Clark Griffith sought to rid himself of the Tennessee-based franchise. A buyer was found within the organization itself — farm director Joe Engel — but the sale was conditioned on a commitment extracted by Engel to let him select a number of players from within the franchise to improve Chattanooga’s on-field product. In November the Senators “carried out their part of the bargain”4 by assigning six players to the Lookouts. One was a player with whom Engel had a close familiarity: Jimmy Bloodworth.

Besides the Lookouts, the Florida native spent a small portion of the 1938 season with the Class-B Charlotte Hornets. The organization’s apparent goal was to convert Bloodworth into more of a power hitter. He posted a combined .410 slugging percentage after three years in organized ball but exploded for a .723 mark in 37 games for the Hornets. As Bloodworth captured sufficient playing time throughout the remainder of his career, the lessons learned in Charlotte invariably placed him among the leaders in home runs for his teams.

In 1939 two developments ensured Bloodworth’s re-emergence on the major-league scene. Since their 1933 American League championship, the Senators had collapsed to the second division in four of five seasons. The 22-year-old fit in nicely with the vigorous youth movement that ensued. Meanwhile Buddy Myer, the 35-year-old second-base incumbent, was suffering from a recurrence of a stomach ailment that plagued him three years earlier and regularly forced him to the bench. Bloodworth was recalled from the Eastern League to fill the void.

Bloodworth actually broke camp in Florida with the Senators in the spring of 1939 but saw only one April at-bat before his reassignment. A .360 batting average in 35 games with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Nationals convinced management it should take a second look at the right-handed hitter. On June 7 Bloodworth began rotating with Myer at second base and his glove work drew rave reviews from columnist Denman Thompson in The Sporting News: “[A]field he has been making daily plays which people have been watching, but still won’t believe. … He is a cracker double-play man.”5 Bloodworth relegated Myer to a pinch-hitting role after setting a .429 pace over 13 games beginning July 30, followed by a 14-game hitting streak starting August 25. He hovered around .300 in August and concluded the campaign with a .289-4-40 line in 318 at-bats. The second-base job would be his to lose.

But lose it Bloodworth nearly did as he suffered through a difficult 1940 spring camp. Though he had plenty of company struggling in Florida, he drew considerable criticism from the same writers who had fawned over him the year before. The 1940 Senators suffered a 90-loss season — the most since 1911 — and although Bloodworth placed among the team leaders in homers (11) and RBIs (70), he was constantly cited for a low batting average (.245; league average: .271). Pitchers had discovered his weakness on breaking pitches. “I don’t know what to think of Bloodworth,” Clark Griffith said. “He’s got plenty of power and he’s hit a lot of home runs, but he still goes for that outside curve ball and isn’t consistent. He isn’t fast in the field and doesn’t cover too much ground, but where is there a fellow with better hands than Bloodworth?”6

Bloodworth’s 1941 line of .245-7-66 for the sixth-place Senators mirrored his preceding campaign. Offseason speculation arose that he would be moved to third base in 1942 to make room for another budding second-base prospect. The shift never took place. In a four-player swap on December 12, 1941, the Tigers acquired Bloodworth to replace retiring second baseman Gehringer. Bloodworth was not Detroit’s first choice — the Tigers had approached Boston about future Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr – but they were ecstatic over their second choice and his “hustling spirit.”7 In 1942 Bloodworth again placed among the team leaders in many offensive categories, including his major-league single-season high 13 homers. After a slow start in 1943, Bloodworth surged to a .293 average in 75 at-bats beginning May 9 that seemingly signaled more. But injuries limited him to 25 June at-bats and he finished the campaign with a .241-6-52 line. Thirty-one months would pass before he saw his next major-league pitch.

The 26-year-old Bloodworth was inducted into the US Army on November 4, 1943, and assigned to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, throughout the remainder of World War II, where his skills as a marksman qualified him as an instructor. He played shortstop for the base team and drew national attention after striking a home run against the St. Louis Cardinals in an August 1944 exhibition. Bloodworth received his honorable discharge in the spring of 1946 and, with the season under way, reported to Detroit’s Briggs Stadium for a week of workouts before his mid-May reunion with the Tigers. Once activated, he was relegated to two pinch-hit appearances through the remainder of the month.

When Bloodworth entered the Army, the Tigers secured veteran infielder Eddie Mayo to fill the void. Mayo’s presence promptly thrust Detroit into pennant contention, earning him consideration for the American League Most Valuable Player in 1944 and 1945. Mayo was putting together another fine season when injury sidelined him on June 3, 1946.

Bloodworth stepped in immediately. Beginning on June 8, he set a .329 pace through the remainder of the month that helped keep the Tigers in contention, making him a “warmly welcomed”8addition. But injury found Bloodworth as well. On July 28 he suffered a cracked elbow from a pitched ball that limited him to 17 August at-bats. For the season he hit .245 in 249 at-bats. Though Bloodworth finished strong, the Tigers announced in November that Mayo would retain his starting role in 1947 upon his healthy return. In December Bloodworth was sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates for $10,000.9

The 1946 Pirates initiated a vast overhaul of their roster after a 91-loss season. Two offseason acquisitions, Eddie Basinski and player-manager Billy Herman, represented Bloodworth’s immediate competition for the second-base position. Through the first 13 games of the 1947 campaign, Jimmy had two plate appearances. But the Pirates were not through with their overhaul. On May 3 they traded outfielder Al Gionfriddo to the Brooklyn Dodgers for five players and were forced to make roster moves. The Pirates initially optioned Roy Jarvis and Gene Mauch but both were claimed on waivers. They turned to Bloodworth, who cleared waivers and was assigned to the Triple-A Indianapolis Indians. Bloodworth balked at the demotion but Herman promised him a quick return.

Herman proved true to his promise. In 1947 the platoon of Herman and Basinski combined for a .202-4-23 line. The team turned to Bloodworth for improvement. Inserted into the starting lineup on July 4, Bloodworth collected 6 hits in 16 at-bats — including his first National League homer — as he raised his batting average over .300. Eleven days later he exploded for a .469 clip (15-for-32) in eight games. In an August surge Bloodworth hit safely in 18 of 21 games including a 10-game hitting streak. On August 21 he hit an eighth-inning single that ruined a no-hit bid by New York Giants righty Clint Hartung. This surge was countered by a dreadful September (.175) as Bloodworth finished the year with a .250-7-48 line.

But the Pirates were still not through overhauling the roster. Near the end of another campaign of more than 90 losses, Herman was fired before the last game of the 1947 season. Bloodworth soon followed when he was included in a three-player swap with the Dodgers. In 1948, with little chance of unseating Brooklyn’s second baseman, reigning Rookie of the Year Jackie Robinson, Bloodworth was assigned to the Triple-A Montreal Royals.

The Royals 1948 roster, with future Hall of Famer Duke Snider and right-handed pitcher Don Newcombe, was the envy of many major-league teams (Chuck Connors, later famous on TV as the star of The Rifleman series, was Bloodworth’s roommate). The team raced to the International League crown and prevailed in the Junior World Series against the St. Paul Saints in part due their second baseman, Jimmy Bloodworth. Overlooking the fine campaign posted by Jackie Robinson in 1946, Bloodworth was “rated by at least one veteran Montreal scribe as the best second sacker the Royals have had in at least 20 years.”10 He tied a team record with three consecutive homers in a game and his .294-24-99 line earned an All Star selection, and later MVP honors,11 by the International League Baseball Writers’ Association. When reports emerged that Clay Hopper, Montreal’s manager, hoped to move to the majors, Bloodworth declared his desire to take the managerial reins for the 1949 Royals. He received a boost from Paul Richards, manager of the Buffalo Bisons, who opined, “Bloodworth means as much to Montreal as Burgess Whitehead did in Jersey City’s pennant drive last year. Both are real leaders on the field.”12

But Bloodworth’s managerial pursuits would be delayed. His sterling campaign, combined with his overriding desire to return to the majors, attracted many scouts. Before the 1948 Junior World Series got under way the Cincinnati Reds acquired Bloodworth for a player to be named later and a “fat bundle of cash.”13 Like many teams Bloodworth was connected with, the Reds were engaged in a youth movement and Bloodworth — whose graying hair caused him to appear older than his 31 years — became the “old man” on the 1949 squad. His veteran presence (he played every infield position save shortstop) helped stabilize the youthful corps as they suffered through a 92-loss campaign. In 134 games he batted a solid .261 with 9 home runs. In 484 plate appearances, he struck out only 36 times.

In the spring of 1950 Bloodworth prevailed in the four-player competition for the Reds’ second-base position. But after just four games, Reds management reversed course and inserted Bobby Adams into the role. Bloodworth did not play another game for Cincinnati. On May 10 Cincinnati acquired infielder Connie Ryan from the Boston Braves and sold Bloodworth to Philadelphia. Though Bloodworth got little playing time with the Phillies (only 96 at-bats because the regular infielders missed just 15 games combined), he drove in the winning run twice: an eighth-inning pinch-hit three-run double on June 30 against the Dodgers and a ninth-inning sacrifice fly RBI on August 30 against the St. Louis Cardinals

The 1950 National League pennant came down to the last day, when Dick Sisler’s homer against the Dodgers in the 10th inning sent the Phillies to the World Series against the New York Yankees. Bloodworth’s Series experience proved to be of the dubious sort.

On October 6 Philadelphia entered Game Three down two games to none and trying desperately to crawl back into the Series. They led 2-1 in the eighth, but shortstop Granny Hamner and Bloodworth “played soccer with a couple of grounders” in the eighth and ninth.14 An error by Hamner allowed the tying run to score in the eighth. Bloodworth entered the game in the bottom of the ninth as a defensive replacement at second base. Russ Meyer got two outs, then the Yankees got two straight infield hits on balls hit to Bloodworth.

Though he wasn’t charged with an error, the game summary describes a momentary bobble by Bloodworth that allowed the first hit (the official scorer felt the batter would still have beaten out the play). A clean play by Bloodworth might have accounted for the third out and allowed the Phillies a possible extra-inning comeback. Instead, the Yankees’ Jerry Coleman struck a walk-off single and the Phillies went down to defeat. The Yankees completed the Series sweep the following day.

The Phillies found consolation in the thought that with their young talent, the team would witness a rapid return to postseason play. This was not to be. In 1951 Philadelphia plummeted to a second-division finish, for a host of reasons. One was the second base situation; seven players manned the position during the season but collectively accounted for a meager .213-10-61 line. Bloodworth saw little of this time (even less — six games — at first base) as he got just 42 at-bats. As the season ground to its final weeks Bloodworth requested and was granted his release.

Bloodworth enjoyed life and made friends easily. Two famous friends had a major influence on the direction his career took next. That offseason, Bloodworth’s former teammate in Detroit and Pittsburgh, Hank Greenberg, was Cleveland’s general manager. He invited Bloodworth to join the Indians coaching staff. Greenberg knew of Bloodworth’s on-field teaching skills, decribed this way by Bloodworth’s 1948 teammate Bobby Morgan: “Jimmy taught me more about fielding my position and about the double play than anyone I ever knew.”15 But Bloodworth declined Greenberg’s offer. He still retained notions of returning to the majors as either a player or manager. This latter course was encouraged by another friend, Branch Rickey, and Bloodworth was willing to pursue becoming a manager by working his way up through the minors. He accepted Greenberg’s next offer, to be the player-manager of Cleveland’s Cedar Rapids farm club in the Class-B Three-I League. When the 1952 season began, Bloodworth surprised few when he began inserting himself on the mound for the Indians.

Bloodworth had previously sought to recast himself as a pitcher in 1947 during his brief stay in Indianapolis. Billy Sullivan, the team’s catcher, claimed Bloodworth possessed the best knuckleball he’d seen. But his request to pitch fell on deaf ears with a promise to re-evaluate the decision in 1948. The project was shelved when Bloodworth was recalled by Pittsburgh. Sullivan’s assessment proved accurate five years later when manager Bloodworth, in control of his own destiny, obtained a measure of success from the mound. Shifted to the Spartanburg (South Carolina) Peaches in 1953 after the Iowa affiliate switched allegiance to the Chicago Cubs, Bloodworth placed among his team leaders in ERA for two consecutive seasons while posting some remarkable performances. On June 21, 1953, he struck out 10 Rock Hill Chiefs in a relief outing to secure a 9-8 win. Returning two weeks later to frustrate the same Chiefs, he set them down in order in the ninth after hitting a pinch-hit homer to put his team in the lead. Bloodworth played every position save catcher while at various times placing among the Tri-State League leaders in hitting. Bloodworth’s piloting success earned managerial honors in the league’s 1953 North-South All Star game amidst his rumored advancement to Class A in Reading, Pennsylvania. His tutelage in the Cleveland organization helped the careers of Rocky Colavito, Gordy Coleman, and Bud Daley.

The Peaches stumbled to a 66-72 record in 1954 and suffered further indignity in a series of events in which Bloodworth played a bit part. On August 1 the Spartanburg team owners announced their withdrawal from the Tri-State League after a game in Knoxville, Tennessee, in which Aldo Salvent, a dark-skinned Cuban, played third base for the Smokies. Peaches president R.E. Littlejohn canceled the remaining three games of the series and ordered Bloodworth and the team to return to Spartanburg. Littlejohn had promised the City Parks Board he “would not allow his team to play a Negro.”16 The league directors calmed Littlejohn by arranging Salvent’s transfer to another league. It is unclear whether this incident played a part, but four months later Bloodworth resigned from the Peaches. He accepted a job with his old employer, the Washington Senators, to manage the team he played for in 1938, the Charlotte Hornets (since elevated to Class A).

Bloodworth had even less success in the South Atlantic League as the team struggled through a miserable 54-86 season. In late July losses mounted at such a rate that the Hornets general manager publicly reprimanded the players while declaring his full support for his beleaguered skipper. The support mattered little when Bloodworth was ousted before the start of the 1955 season. As a result, after 19 years, Bloodworth’s career in Organized Baseball was at an end.

In Montreal during Bloodworth’s 1948 MVP campaign, the strong family man pined for home as his wife was delivering the second of their three sons. Bloodworth had married the former Maurice Norred in Apalachicola, Florida, on February 14, 1941. She was a fellow Chapman High alum five years his junior; he’d begun dating the valedictorian in her senior year. All of “five-foot tall with a big personality,” she maintained such a hawkish control of their personal finances that “she could squeeze the head off a nickel.” The marriage lasted 58 years until she died of cancer in 1999.

During his playing career Bloodworth returned to Apalachicola every offseason and found employment at a paper mill in nearby Port St. Joe. After an unsuccessful mid-1950s run for Franklin County sheriff, the accomplished carpenter rose to shop foreman at the mill. He built a house in Apalachicola that, during a 1963 Whiz Kids reunion, he dubbed “the home Sisler built”17 (a reference to his $4,200 World Series share made possible by Sisler’s 1950 pennant-clinching homer). His spare time was spent hunting and fishing with his sons, who themselves went on to success on the collegiate baseball diamonds and football fields. When he hauled in a catch with homemade fishing nets, or game from his frequent hunting expeditions, that fish or game frequently made it to the dinner tables of neighbors.

Earlier Bloodworth had inspired a song made popular in one of the many Bob Hope-Bing Crosby “Road to” movies. Crosby was part-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1946 when he casually inquired of Bloodworth’s hometown. The famous singer was taken by the response of “Apalachicola, F-L-A.” A song by that name, sung by Crosby and the Andrews Sisters, became a part of “Road to Rio.”

Jimmy Bloodworth was also known for his wry humor. In 1950 he had an opportunity to poke fun at the salaries of some of baseball’s highest-paid players in a moment captured by The Sporting News:

“[Players] joke about the big dough of the big-shot stars. At least Jimmy Bloodworth of the Reds reacted with a sense of humor when he noted [Joe] DiMaggio and [Stan] Musialplaying gin rummy the other day at St. Pete. As Bloodworth walked away from their card game, a baseball writer asked him, ‘How much are those two playing for?’ Said Bloodworth, ‘Those two are probably playing for Cadillacs.’”18

This same humor did not depart in his later years when his health began to fail: “I could never fall victim to Gehrig’s disease. He was a much better player.”

In 1975 the 58-year-old suffered a heart attack. Nearly 30 years later, the last three of which found him bound to a wheelchair, Bloodworth succumbed to heart disease on August 17, 2002. He was survived by three sons and three of four grandchildren. He was buried in the Magnolia Cemetery in Apalachicola.

Bloodworth’s major-league career concluded after 1,002 games with a lifetime .248 average. His 11-year endeavor was interrupted by war and when he returned, his position was occupied. Shortly thereafter, he was saddled with the label of utility-player. War has interrupted or terminated many a career, so Jimmy Bloodworth does not stand alone. But one is left to speculate how his career might have turned out had the 25-year-old been able to develop uninterrupted at the major-league level.

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Darryl, Leon, Richard, and Ronald Bloodworth for the recollections of their father/uncle. Collectively they are the sources for all unattributed quotes. The Bloodworths were interviewed at different days from September 19 through September 23, 2014.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

sabr.org/bioproj/person/ce6e3ebb

apalachicolarealtyinc.com/bing_crosby.aspx

Notes

1 “Bloodworth Wins TV Set as MVP in City Series,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1950, 10.

2 Interview with Leon Bloodworth, September 2014.

3 “Youthful Senators Pile Up Heavy Vote,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1937, 2.

4 “Walter Millies Named Chattanooga Manager,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1937, 5.

5 “Nats ‘$100 Infield’ Looks Like Million,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1939, 5.

6 “Nats’ Chief ‘Poofs’ Poffenberger Deal,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1940, 14.

7 “Baker Long On Hill, Longs For Hitting,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1942, 2.

8 “Redhot Reserves Help to Keep Tigers in Stride,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1946, 13.

9 A second source cites $7,500.

10 “International League: Montreal,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1948, 26.

11 Bloodworth was the first Montreal player to secure International League MVP honors since its inception in 1932.

12 “International League: Twin Wins Helping Royals Pull Away,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1948, 21.

13 “McCahan in Dodger Bid,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1950, 18.

14 “Clubhouse Confidential,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1958, 16.

15 “Morgan Nails Down Dodger Loose Spot at 3rd,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1950, 9.

16 “Peaches Rejoin Tri-State After Smokies Ship Negro,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1954, 37.

17 “Sisler’s Flag Homer Built Bloodworth’s Florida Home,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1963, 13.

18 “’Cadillacs’ at Stake When Stan and Jolter Tangle at Gin Rummy,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1950, 6.

Full Name

James Henry Bloodworth

Born

July 26, 1917 at Tallahassee, FL (USA)

Died

August 17, 2002 at Apalachicola, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.