Joe Mulvey

From 1883 to 1892, third baseman Joe Mulvey contributed offensively and defensively to Philadelphia teams. According to sportswriter Tim Murnane, Mulvey was one of the seven greatest third basemen of the 19th century, along with Billy Nash, Ezra Sutton, Bob Ferguson, Jerry Denny, Tom Burns, and Art Whitney.1

From 1883 to 1892, third baseman Joe Mulvey contributed offensively and defensively to Philadelphia teams. According to sportswriter Tim Murnane, Mulvey was one of the seven greatest third basemen of the 19th century, along with Billy Nash, Ezra Sutton, Bob Ferguson, Jerry Denny, Tom Burns, and Art Whitney.1

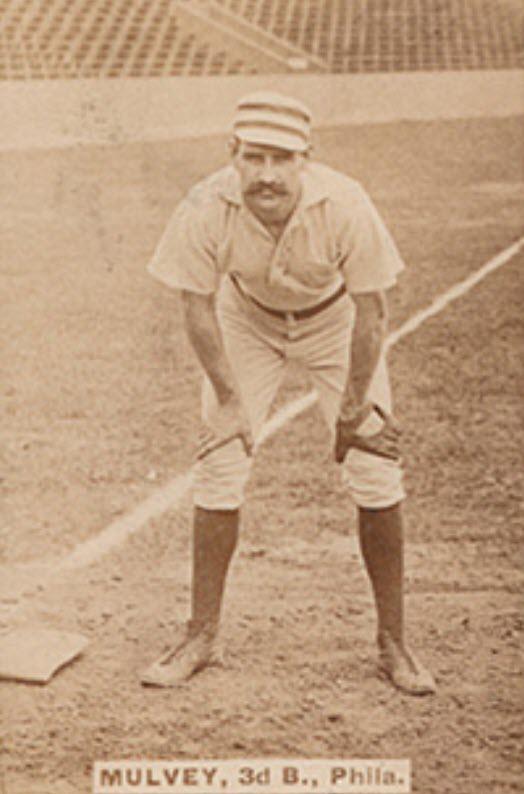

It takes courage to play at the hot corner in any era, but it was especially challenging in the 19th century. Wearing no glove or only a thin one (see photo), Mulvey endured bruised hands and broken fingers. “His pluck in facing hard hits and his hard hitting make his services indispensable,” said the Philadelphia Times.2

Mulvey gathered grounders and made “lightning” throws to first base. “Sir Joseph” had exceptional range, running to his left for one-handed pickups or to his right to catch foul popups. And in the words of Sporting Life, he was “the greatest bunt eater on the diamond.”3

Joseph Henry Mulvey was born on October 27, 1858, in Providence, Rhode Island. He was the fifth of six children of Irish immigrants, Thomas and Catherine Mulvey. Thomas worked as a mason.4 As a young man, Joseph worked for a jeweler in Providence5 and played on local baseball teams. In 1879 he was a shortstop and batted leadoff for the Gortons, a top amateur club.6

In the spring of 1883, Sporting Life said Mulvey was “considered a phenomenon, resembling [Jack] Glasscock in build and action. His home position is short-stop … and [he] wields a bat with powerful effect.”7 That year Mulvey appeared in seven National League games — four at shortstop for the Providence Grays, with whom he made his major-league debut on May 31, and three games at third base for the Philadelphia Phillies.8

Mulvey was put out of action for several weeks by a bizarre incident in Providence on June 27, 1883. Reportedly, Providence outfielder Cliff Carroll sprayed a fan named James Murphy with a water hose during morning practice. Murphy was incensed; he left the ballpark and returned with a gun. He shot at Carroll but missed and hit Mulvey in the shoulder. Mulvey received “a painful but not serious flesh wound,” and Murphy was arrested.9

Mulvey was the Phillies shortstop in a postseason series against the Philadelphia Athletics. On October 15, 1883, he made “three difficult stops and a line catch with his left hand, which brought forth uproarious applause.”10 He preferred to play third base,11 and he became the Phillies’ regular third baseman in 1884.

A right-handed batter and thrower, Mulvey was 5-feet-11 and weighed 165 pounds.12 He struggled as a rookie on the 1884 Phillies. In 405 plate appearances, he batted .229 with only 15 extra-base hits and four bases on balls. Moreover, he led National League third basemen with 73 errors. He had a particularly bad day on July 30 against the Boston Beaneaters, when he committed six errors, establishing an NL record for third basemen that went unmatched through 2019.13

But Mulvey quickly improved. In 1885 he led the Phillies in hits, doubles, triples, home runs, and runs batted in. He seemed to own Buffalo pitcher Pud Galvin. Mulvey hit a single, double, and triple off Galvin on May 25, and got two more singles and a home run off him on July 3.14 In 1886 Mulvey homered off Chicago’s John Clarkson on May 22, and clouted a double and triple off New York’s Tim Keefe on August 19.15 Galvin, Clarkson, and Keefe were future Hall of Famers.

Mulvey’s fielding was cited as “the principal feature” of the game of August 24, 1887, against Indianapolis: “He made two wonderful catches of foul fly hits, and he also made a remarkable stop of a hot hit from [Jerry] Denny’s bat.”16 Mulvey could catch a hot liner barehanded without wincing,17 though it surely stung. In 1888 he began wearing a glove.18

In the second game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia on May 30, 1888, Mulvey stepped to the plate with two men on base and stroked a triple off Detroit’s Pete Conway. The Times colorfully described the at-bat:

“Joe was always good with men on bases, and he was better than good this time. The crowd became very quiet after two balls had passed over the plate, but it was only the lull which precedes the storm. Mulvey finally lit on the ball and sent it out between left and centre fields. Two runs came in and the enthusiasm of the roaring mass of humanity lent wings to Mulvey’s feet and he didn’t stop until he reached third base. It was a good long three-baser and Mulvey had to lift his cap many times before the crowd was satisfied.”19

Mulvey’s 1888 season average was .255 in mid-June when he was sidelined by an undisclosed injury.20 He returned to action in late July but wasn’t himself; he averaged .195 in the remainder of the season. Nevertheless, he got the sole Phillies hit on September 5 to prevent a no-hitter by New York pitcher Mickey Welch, another future Hall of Famer.21 Three days later, in the second game of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh, Mulvey proved again to be Galvin’s nemesis: He singled off Galvin in the ninth inning to drive in the winning run.22

Sporting Life reported that Mulvey was “the life of the team” with his humor. His teammates and manager, Harry Wright, enjoyed “his imitations of the different peculiarities of League players” and his seemingly endless supply of jokes.23 “I have frequently seen Harry laugh until he had to sit down at some of Mulvey’s quaint sayings and doings,” said Mulvey’s teammate Ed Andrews.24

Mulvey batted .289 in 1889, a career high. Facing Keefe on July 22, he went 5-for-6 with four runs batted in, and his single in the top of the 11th inning scored the go-ahead run in a 10-9 Phillies victory.25 “It is seldom that Tim Keefe is hit so successfully by one man in any one game,” noted the Times.26 On August 12 Mulvey slugged two home runs off Chicago’s John Tener and a week later belted a grand slam off Washington’s Alex Ferson.

The Times effused over Mulvey’s defense on September 3. In the eighth inning, Chicago’s Tom Burns “sent one screaming over third base, but Sir Joseph made a dive for the ball and caught it just as it was passing him. He recovered quickly, and by a lightning throw cut the runner off at first.”27

At the end of the 1889 season, Sporting Life declared, “With the possible exception of [Jerry] Denny,” Mulvey “put up a better game at third than any other third baseman in the League — or, for that matter, in the country.”28 Denny, though, conceded that Mulvey was “the best third baseman in the business,”29 and the Philadelphia Inquirer called Mulvey “the King of Third-basemen.”30 Keefe, too, regarded Mulvey as “the best third baseman in the country.”31

Mulvey became a controversial figure after the 1889 season. In November he signed a contract with the Philadelphia club of the newly formed Players’ League, yet a month later he signed with the Phillies. Desperate to keep their star third baseman, the Phillies offered him a raise from $2,000 to $2,750 for the 1890 season and paid him $1,250 in advance. It was then assumed that he would return to the Phillies, but he ultimately decided to play in the Players’ League. However, he did not return the $1,250 he received from the Phillies, and he was deservedly chided in the press for it.32

Mulvey’s new team staged its opener in Philadelphia on April 30, 1890, in front of 17,182 fans. “A more enthusiastic crowd was never present at a ball game.”33 With two men on base in the fourth inning, Mulvey drove a pitch from Boston’s Matt Kilroy to the left-field fence; “Mulvey did not stop at third, but continued on the run for the plate, which he reached in safety on [Billy] Nash’s high throw to [catcher Michael ‘King’] Kelly.”34

Against Chicago on May 30, in the second game of a doubleheader, “Mulvey’s work at third was the finest ever seen in Philadelphia, two of his catches, one with his left hand, being simply phenomenal, and his double play was alone worth the price of admission.”35 Sporting Life said, “Mulvey is playing the game of his life this spring. He fairly eats base hits, bats hard and timely and runs the bases with better judgment than any of the other Philadelphia brothers.”36

Mulvey went on a tear at the plate while on the road during the final week of July. In six games he was 11-for-24 (.458) with seven extra-base hits.37 At season end, he had achieved career highs in runs, doubles, triples, RBIs, walks, total bases, and slugging percentage. But there was one problem looming. The Phillies organization filed suit against him on October 11 seeking to recover the $1,250 he owed.38

The Players’ League folded after the 1890 season, and the Phillies hoped to sign Mulvey to a contract for 1891. Phillies President Al Reach said, “Mulvey will probably be retained at third, for we could not secure a better player for the position. I consider him the strongest third baseman in the League.”39 But Mulvey was not eager to return to the Phillies. He chose instead to sign with the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association and continued to dodge repayment of his debt to the Phillies.

On May 2, 1891, the Athletics edged the Baltimore Orioles, 5-4, in Philadelphia. In the fourth inning with two men on base, Mulvey “gauged” a curveball from Baltimore ace Sadie McMahon “and catching the sphere on the end of his ash stick sent it whirling merrily through the atmosphere toward the left centre bleacheries. It was a terrific hit and oh! my, how that crowd did yell. Mr. Mulvey skipped round the bases like a young gazelle and before the ball could be returned he had crossed the plate safely.”40

Mulvey feasted on Louisville Colonels pitching in May. In consecutive games against the Colonels, May 12-13, he went 7-for-11 with three triples and a home run.41 Again against Louisville, May 26-27, he went 7-for-10 with three more triples.42

On defense, Mulvey continued to shine. Regarding his performance against Columbus on July 20 in Philadelphia, the Times said, “Sir Joseph … gave as pretty an exhibition of third base play as has ever been seen in this city. Four of his six assists were of the gilt-edge order. All of them were hard hit grounders. He covered a large slice of territory in gathering them in, and he lost no time in getting the ball over to [first baseman Henry] Larkin.”43

In August Mulvey’s stellar fielding at Boston earned praise from the Boston Herald:

“Joe Mulvey can still lay claim, without the least fear of contradiction, to being the best third baseman in the country. He is acknowledged to be the best man on bunted balls in the country, and the way he handled fouls on the run in this city was never surpassed. He simply ate up base hits, and the fiercest grounders have no terrors for him.”44

Mulvey’s .894 fielding percentage in 1891 was his career high at the major-league level. Only Art Whitney, with a .902 rate, ranked higher among the league’s third basemen.

Mulvey married Anna Rosa Rombold in Philadelphia in 1891. She was a native of Philadelphia and a daughter of German immigrants.45 In January 1892 the young couple welcomed twin boys, Joseph Henry Jr. and George Albert.46 It was a “two-base hit” for father Joe, quipped Sporting Life.47 A daughter, Kathryn, would be born in 1893.48

The American Association folded after the 1891 season. That left the National League as the sole major league, and Mulvey finally agreed to rejoin the Phillies. It was not disclosed whether his debt to the club was deducted in whole or in part from his 1892 salary. He fell ill and appeared in only 25 games for the Phillies before he was given his unconditional release in late June. According to one report, Mulvey suffered from Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment.49

Mulvey was well enough to appear in 55 games for the Washington Senators in 1893 but left the team in July on account of illness.50 He felt better the following spring and was given a tryout by Washington, but the Senators elected to go with Bill Joyce as their third baseman. So Mulvey signed with King Kelly’s Allentown (Pennsylvania) club,51 joining a group of aging former major leaguers that included Pete Browning, Henry Larkin, Jocko Milligan, Sam Wise, and George Wood. Nicknamed “Kelly’s Killers,” the team was described variously as a “galaxy of stars” and an “aggregation of relics.”52 Mulvey performed well in the field and at the plate, and in November 1894, at the age of 36, he was signed by the Brooklyn club of the National League.

Mulvey appeared in 13 games for Brooklyn in the spring of 1895 and was released in June. He played well, but the club needed to reduce the size of its roster.53 He would never again play in the major leagues, but he was not finished as a professional ballplayer. He was immediately welcomed back by the Allentown club, now managed by Milligan. The Allentown Leader was thrilled: “Sir Joseph … is always a gentleman, always conscientious, sober, and industrious, [and] he will be an invaluable addition to Milligan’s aggregation.”54 During one stretch with Allentown, from July 10 to 16, Mulvey went 15-for-27 (.556) at the plate.55 However, his season ended early when the Allentown team disbanded on July 25.56

In 1896 Mulvey hit .282 in 113 games for the Rochester (New York) Blackbirds of the Eastern League, and he led the league’s third basemen with a .938 fielding percentage.57 He appeared in 58 games for Rochester in 1897 but left the team in July before it was transferred to Montreal.58 The following spring, he declined to join Montreal and chose instead to retire.

Mulvey resided in Philadelphia. He managed a shuffleboard parlor, 1898-99, and a pool room, 1900-04, and in 1910 he was a bartender at a saloon.59 In the 1920s, he was a watchman at Baker Bowl, the Phillies’ ballpark, and it was there that he suffered a heart attack and died on August 21, 1928, at the age of 69.60 He was buried at the Magnolia Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Len Levin and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Ancestry.com (accessed March 2020).

Photo: Kalamazoo Bats cigarette card, circa 1888.

Notes

1 T.H. Murnane, “Murnane’s Ball Talk,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 28, 1903: 12.

2 “The Base Ball Men,” Philadelphia Times, March 28, 1886: 2.

3 “Baltimore Bulletin,” Sporting Life, April 18, 1891: 5.

4 1865 Rhode Island Census.

5 1880 US Census.

6 “Atlantics vs. Gortons,” Boston Globe, May 8, 1879: 1; “Brocktons, 10; Gortons, 4,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1879: 2.

7 “Who Is Mulvey?” Sporting Life, May 6, 1883: 3.

8 Baseball-reference.com, accessed March 2020, referred to the Philadelphia team as the Quakers, but period newspapers called them the Phillies.

9 “A New Pitcher Coming,” Philadelphia Times, June 28, 1883: 1.

10 “Athletic vs. Philadelphia,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1883: 4.

11 “Providence Items,” Sporting Life, November 28, 1883: 2.

12 “Joseph Mulvey,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 30, 1891: 3.

13 “Error Records for Third Basemen,” Baseball-almanac.com/rb_3ber.shtml.

14 “The Buffalos Defeated,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 26, 1885: 3; Sporting Life, July 8, 1885: 3.

15 “Again Victorious,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 20, 1886: 3.

16 “National League,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 25, 1887: 3.

17 “Turning the Tables,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 31, 1887: 3.

18 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, May 16, 1888: 2.

19 “The Phillies Win,” Philadelphia Times, May 31, 1888: 3.

20 “The Phillies’ Players,” Philadelphia Times, June 17, 1888: 7; “League Averages,” Sporting Life, June 20, 1888: 2.

21 “The League Games,” Philadelphia Times, September 6, 1888: 4.

22 Sporting Life, September 19, 1888: 3.

23 Sporting Life, March 13, 1889: 5, and March 27, 1889: 5.

24 “Memories of Harry Wright,” Philadelphia Times, October 27, 1895: 17.

25 “A Great Game of Eleven Innings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 23, 1889: 6.

26 “The League,” Philadelphia Times, July 23, 1889: 4.

27 “The League,” Philadelphia Times, September 4, 1889: 3.

28 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, October 16, 1889: 5.

29 “Base-Ball Notes,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1890: 6.

30 “Joseph Mulvey,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 30, 1891: 3.

31 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, January 9, 1892: 3.

32 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, November 20, 1889: 3; “The League in Court,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 15, 1889: 6; “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, April 5, 1890: 3; “Mulvey to Be Prosecuted,” Sporting Life, May 3, 1890: 9.

33 Sporting Life, May 3, 1890: 3.

34 “Players’ Opening Day,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 1, 1890: 1, 2.

35 Sporting Life, June 7, 1890: 3.

36 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, June 7, 1890: 4. The Players’ League was known as “the Brotherhood,” and Mulvey’s teammates were his “Philadelphia brothers.”

37 Sporting Life, August 2, 1890: 3.

38 “Suit against Joe Mulvey,” Chicago Tribune, October 12, 1890: 6.

39 “Cincinnati Chips,” Sporting Life, February 7, 1891: 6.

40 “Barnie’s Baltimoreans Beaten,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1891: 3.

41 Sporting Life, May 16, 1891: 4.

42 Sporting Life, May 30, 1891: 4.

43 “American Association,” Philadelphia Times, July 21, 1891: 3.

44 Boston Herald quote reported in: “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, September 5, 1891: 3.

45 1870 US Census.

46 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, February 13, 1892: 4.

47 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, February 6, 1892: 4.

48 1900 US Census.

49 “Philadelphia Pointers,” Sporting Life, June 4, 1892: 2.

50 “Mulvey’s Old Habit,” Sporting Life, August 5, 1893: 11. Mulvey returned to action briefly in August 1893 and appeared in four games with the Reading team of the Pennsylvania State League.

51 The 1894 Allentown team began the season in the Pennsylvania State League and moved to the Eastern League in August, replacing the disbanded Binghamton (New York) team.

52 “Exciting Twelve Inning Game,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Tribune, June 13, 1894: 2; “Kelly’s Killers,” Buffalo Courier, September 9, 1894: 20.

53 “Brooklyn Budget,” Sporting Life, June 15, 1895: 11.

54 “Sir Joseph Coming,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Leader, April 20, 1895: 4.

55 Sporting Life, July 20, 1895: 22.

56 “Pennsylv’a League,” Sporting Life, August 3, 1895: 16.

57 Sporting Life, November 28, 1896: 6.

58 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, August 7, 1897: 5.

59 Sporting Life, June 11, 1898: 4, February 11, 1899: 3, and March 26, 1904: 3; 1900 and 1910 US Censuses.

60 “Joe Mulvey, Old-time Ball Player, Found Dead,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1928: 18.

Full Name

Joseph H. Mulvey

Born

October 27, 1858 at Providence, RI (USA)

Died

August 21, 1928 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.