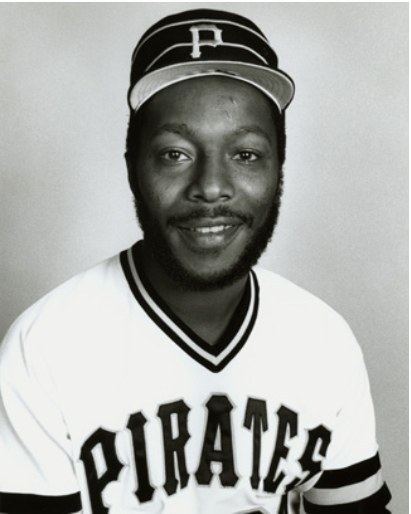

John Milner

John Milner idolized Hank Aaron, lockered next to Willie Mays, and on his best days could hit home runs with as much authority as either man. While injuries and inconsistency prevented Milner from becoming an elite slugger, he carved out a 12-year career for the Mets, Pirates, and Expos, helping each of those clubs reach postseason play. And though a quiet sort in his playing days, Milner’s post-career testimony about drug use provided a direct and unflinching peek into the dark side of the game as it was played in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

John David Milner was born on December 28, 1949, in Atlanta, the second of Johnny Sims and Addie Milner’s three children. Addie raised the Milner children herself on modest wages as a domestic housekeeper and with the help of a large extended family around the Atlanta suburb of East Point, where they lived. (John Milner was an older cousin of Eddie Milner, who had a nine-year major-league career from 1980 to 1988 playing for Cincinnati and San Francisco.)

Like most African-American residents of East Point, the Milners lived in the East Washington community, a section of the city segregated under 1912 Jim Crow laws. The area was adjacent to steel mills and fertilizer plants that drew its early residents, mostly Southern farmers seeking steady work amid a declining agricultural economy.1

Segregation was a defining influence for residents of the area, who often found themselves struggling for the same access to services and benefits afforded wealthier white residents. In the 1950s and 1960s of Milner’s youth, black children and teenagers of East Point were prohibited from participating in Little League baseball with white children. They instead participated in separate Pony Colts and Pony Leagues organized by a noted community activist, Oscar James “O.J.” Hurd, and supported by contributions from a local grocery store. Such community sports programs kept kids off the streets, and fed the segregated South Fulton High School, which became known statewide for the successful teams and athletes it produced in the 1960s, including Charlie Greer, who became a defensive back for the NFL’s Denver Broncos, and Don Adams, a small forward for NBA teams including the Atlanta Hawks and Detroit Pistons. Milner, who graduated from South Fulton in 1968, garnered All-State recognition as a halfback in football, a guard in basketball, and a baseball outfielder for the Mighty Lions.

Although Milner probably preferred playing basketball to any other sport, only baseball would provide him the opportunity to participate in professionally. And he wasn’t sure that chance would come. Milner had already applied for work with the East Point sanitation department when a Mets scout, Julian Morgan, informed him he’d been selected by the club in the 14th round of the 1968 first-year player draft. Five years earlier, Morgan had signed Cleon Jones, who by then was rounding into the best offensive player the young Mets franchise ever produced. Within a few years, it looked as though Milner might be the next.

Listed at 6 feet and 185 pounds, Milner was a taut, muscular left-handed hitter and thrower. He had fast wrists and a distinct batting stance, keeping his legs close together and his upper body leaning aggressively toward the plate, becoming an attacking dead-pull hitter who could punish pitches left out over the plate. Although scouts invariably noted that Milner “likes to swing the bat,” he was disciplined enough to amass more walks (504) than strikeouts (473) over nearly 4,000 big-league plate appearances. Milner was considered an average corner outfielder with average speed and a subpar arm, and was adequate at first base, where he appeared the most on the field during his professional career. When Gil Hodges was asked what position Milner played best, the Mets manager replied “at bat.”2

Hodges made that remark only weeks before suffering a fatal heart attack that cast a pall over the 1972 spring training for the Mets. Until then the story of the spring had been Milner. Then 22 years old and in his first major-league camp, “The Hammer” — a nickname given to Milner because of his admiration for, and resemblance to, “Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron — had earned the team’s Johnny Murphy Award as the best rookie in camp and won a job as the team’s regular left fielder.

Milner had made his major-league debut the previous season during a September 15, 1971, doubleheader at Shea Stadium against the Chicago Cubs. In the opener he grounded out as a pinch-hitter facing Bill Hands in his first big-league plate appearance, then started in left field in the second game and singled to right off Burt Hooton for his first major-league hit. Milner had been called up from the Tidewater (Virginia) Tides of the Triple-A International League, where he had slugged 19 home runs while batting .290. This solid production was on the heels of All-Star seasons for the Mets’ farm clubs in Marion (Virginia) of the Rookie-level Appalachian League (1968), Visalia of the Class A California League (1969), and Memphis of the Double-A Texas League (1970).

Milner ripped 17 home runs as a rookie — the most for a power-thirsty Mets team — and finished a distant third behind a teammate, starting pitcher Jon Matlack (the winner) and San Francisco Giants catcher Dave Rader in the ’72 Rookie of the Year voting. Milner credited the coaching of Whitey Herzog, then the Mets’ farm director, for helping to hone his hitting during stints in the Florida Instructional League in 1970 and 1971.

Milner’s 23 home runs in 1973 and 20 in 1974 also led the Mets. But it wasn’t long before the debate around Milner was about what he hadn’t accomplished.

Most contemporary accounts describe Milner as intense and fiercely competitive, often manifesting itself in an angry disposition. “He could go three for four, including a home run, and the Mets could win by five runs, and yet, when he enters the locker room afterward, he is steaming mad,” writer Dick Schaap observed in 1972.3 Writers found him frosty and uncooperative, and occasionally others did too. He was suspended for three games in 1973 for bumping third-base umpire Lee Weyer in an altercation over a disputed catch. He clashed frequently with Joe Frazier, who managed the Mets in 1976 and early 1977. Milner’s tendency to miss games with recurring ailments — most often sore hamstrings — earned him a “goldbrick” tag, a rap Milner insisted was unfair.4

As might be expected having grown up in the segregated South, Milner was sensitive to race playing a role in such criticisms. When the veteran and former All-Star Cleon Jones fell out of favor and was released just after midseason by the stodgy Mets management in 1975, the inference that he was a bad influence on Milner seemed to doubly insult the younger player. “Why do people always say one player was bad influence on another because the player is black?” Milner said in 1976. “Cleon didn’t hurt me. He helped me. Did they say Cleon was a bad influence when we won the pennant in ’73?”5

Milner’s sister, Sharon, said her brother’s gruff exterior was his means of protecting himself and that he was fun-loving and generous among friends and family. On road trips to Atlanta, Milner loved having black teammates including Jones, Tommie Agee, and Gene Clines as guests at his family’s home, where they would gather for meals prepared by his mother, Addie.

Milner stayed with the Mets through the 1977 season, and though he never blossomed into a star, there were several highlights along the way on both sides of the baseball. Milner snared Glenn Beckert’s soft liner at Chicago to turn an unassisted double play that clinched an improbable NL East division title for the 1973 Mets. In Game Three of the best-of-five 1973 NLCS against the heavily favored Cincinnati Reds, he gloved a smash off the bat of Joe Morgan to begin a 3-6-3 double play that ended with fisticuffs between the Reds’ Pete Rose and Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson before escalating into a bench-clearing event. In the deciding Game Five, Milner fielded a roller hit by Dan Driessen and flipped the ball to Tug McGraw covering first base for the final out. However, instead of reveling in their pennant-winning victory on the field, Milner and the rest of his teammates had to race for the safety of their clubhouse as an estimated 5,000 New York fans stormed the Shea Stadium playing field in a wild celebration. In the top of the 12th inning during Game Two of the World Series, Milner’s hard-hit groundball with two outs was not handled by Oakland’s second baseman, Mike Andrews (his first of two miscues in the inning), and the error paved the way for a Mets victory. The extra-inning loss raised the ire of A’s owner Charlie Finley so much that he attempted to replace Andrews on Oakland’s postseason roster afterward. In 1974 Milner hit a prodigious home run off the Dodgers’ Andy Messersmith that smashed some lightbulbs halfway up Shea Stadium’s massive scoreboard in right center, said to be one of the longest ever hit in that ballpark.6 And he rebounded from a poor 1975 (.191 in 91 games) with what was his best major-league season to-date in 1976, hitting a then career-best .271 with 17 home runs, including three of his 10 career grand slams.

In December of 1977, the rebuilding Mets sent Milner to Pittsburgh as part of a complex four-team, 11-player deal involving the Mets, Pirates, Texas Rangers, and Atlanta Braves.

A fresh start in Pittsburgh seemed to do Milner good for the next two seasons. No longer the feature of the offense as he was at times in New York, Milner settled into a role as a part-time starter at first base and in the outfield, a good fit among a contending team with several African-American stars, including Dave Parker, Frank Taveras, Bill Robinson, Willie Stargell, and later Bill Madlock.

The Pirates finished a game and a half behind the Phillies in 1978 but there was no denying them in 1979, when the team, united behind the Sister Sledge song “We Are Family,” edged the Montreal Expos by two games for the NL East Division title, dispatched Cincinnati in three games during in the best-of-five NLCS for the NL pennant, and fought back from a three-games-to-one deficit to stun the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series.

Milner was a productive member of that championship squad, cracking 16 home runs and driving in 60 runs in 386 plate appearances. He started 85 games, splitting left field with right-handed-hitting counterpart Robinson, and occasionally spelling Stargell at first base. The Pirates caught fire in August, sparked by a five-game weekend series sweep of the Phillies at Three Rivers Stadium. Milner delivered the signature moment with a walk-off grand slam off Phillies left-handed relief ace and former Mets’ teammate Tug McGraw to win the fourth of those five “playoff atmosphere” games, 12-8 — a comeback victory that regained first place for the Pirates from Montreal and keyed a decisive month during which they played .700 ball.

Milner was 3-for-9 with two walks, a double, two runs scored, and one RBI during the World Series.

Milner retained his role as a part-time starter on the 1980 Pirates, although he and the club regressed — Milner lost more than 100 points off his slugging percentage from 1979, and the Pirates dropped to third place in the division. Milner played less in the outfield as Mike Easler settled into an everyday role, although Stargell’s knee woes provided Milner with more time at first base. Milner opted for free agency in late October, but re-signed with Pittsburgh three months later.

On August 20, 1981, the Pirates swapped Milner to the Montreal Expos for first baseman Willie Montañez shortly after games resumed following the nearly two-month player strike. It was the second time Milner was essentially traded for Montañez — the Mets had received Montañez from Atlanta as part of the four-team December 1977 trade. Although the latter swap was hardly consequential, it should be noted that the team trading for Milner came out ahead in both of those deals.

The Expos sought Milner’s power to bolster a club contending for its first playoff appearance in the split-season competition (imposed after the strike) featuring an extra tier of postseason games. He started a handful of games at first base for the Expos but was relegated to pinch-hitting when the Expos installed rookie Tim Wallach in right field and moved Warren Cromartie to first base down the stretch. Montreal edged St. Louis by a half-game for the second half of the NL East crown, and defeated the Phillies three games to two in a special division series. The Expos lost in five games to the pitching-rich Los Angeles Dodgers in the NLCS. Though Milner played very sparingly in the postseason (one hit and one RBI in three plate appearances), 1981 was the third season in which he played a role for an NL East champion in a tight pennant chase.

Pinch-hitting almost exclusively in 1982, Milner was batting just .107 when the Expos released him in early July, and Pittsburgh re-signed him later that month. Milner contributed two pinch home runs for the 1982 Pirates, including his 10th career grand slam.

The Pirates invited the then 33-year-old Milner to training camp in 1983, but released him just prior to Opening Day, ending his career in the big leagues. But it wouldn’t be the last time fans would hear his name.

Milner later revealed that he used cocaine over the last four years of his career, buying as much as seven grams a week and sharing it with his teammates on the Expos and Pirates.7 The revelations came as part of testimony in a grand-jury investigation into a Pittsburgh-based drug ring and the subsequent trials and convictions of two dealers in 1985.

One of several players to testify at the trials, Milner gave particularly direct testimony, providing a glimpse inside baseball that many weren’t ready to see. He described having made a drug deal in the Three Rivers Stadium clubhouse while a game was going on, and also said Willie Mays during his time with the Mets had “red juice” — amphetamines dissolved in a liquid — in his locker. Though Milner said he didn’t see Mays take the drugs, he admitted helping himself to them.8 Mays, by then a Hall of Famer, denied Milner’s charges. It would be many years before the pervasiveness of amphetamine use that Milner described in 1985 would come into better perspective among fans of the game.

Milner returned to East Point after his baseball career and worked in construction with an uncle, his sister said. He was never married or had a family, but aspired to support youth sports as his mentors had. A smoker, Milner developed lung cancer that progressed rapidly, and he died on January 4, 2000, at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. He had just turned 50 years old.

In 2002 the East Point neighborhood sandlot where Milner played football as a youth was rechristened as part of an 18-acre regional sports park. The John D. Milner Athletic Complex hosts youth soccer, football, kickball, and baseball on four lighted fields.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author interviewed Sharon Milner on August 23, 2014, and October 11, 2014, and consulted:

Silverman, Matthew, Swinging 73: Baseball’s Wildest Season (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2013).

baseballreference.com.

Notes

1 Herman “Skip” Mason Jr., East Point, Georgia (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

2 Jack Lang, “Can Milner make a ‘hit’ with Gil?” Newark Star-Ledger, March 24, 1972.

3 Dick Schaap, “What Comes After Dawn’s Early Light?” New York magazine, June 26, 1972.

4 Charley Feeney, “Pirates Acquit Milner On Goldbrick Charge,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1978.

5 Augie Borgi, “Milner: Not Looking Back On Disastrous ’75 Season,” New York Daily News, March 23, 1976.

6 Associated Press, “Monster blow by Milner dims lights,” August 13, 1974.

7 “Milner: 7 grams a week,” New York Daily News (wire services), September 24, 1985.

8 Michael Goodwin, “Milner Tells Court of Buying Cocaine,” New York Times, September 13, 1985.

Full Name

John David Milner

Born

December 28, 1949 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

Died

January 4, 2000 at East Point, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.