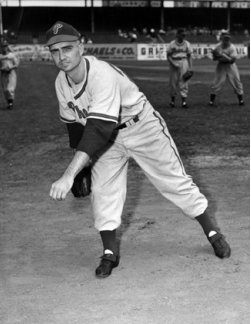

Ken Heintzelman

An accepted piece of conventional wisdom in baseball says that if you can pitch a baseball with your left hand you can pitch for a long time regardless of how well you do so. The rarity of left-handers in general and pitchers in particular make the combination one of the sport’s most coveted assets. One southpaw pitcher who lasted a long time in the major leagues despite consistently average results was Ken Heintzelman.

An accepted piece of conventional wisdom in baseball says that if you can pitch a baseball with your left hand you can pitch for a long time regardless of how well you do so. The rarity of left-handers in general and pitchers in particular make the combination one of the sport’s most coveted assets. One southpaw pitcher who lasted a long time in the major leagues despite consistently average results was Ken Heintzelman.

Kenneth Alphonse Heintzelman was born on October 14, 1915, in Peruque, Missouri, a town about 30 miles west of St. Louis. He was born the day after the last game of the 1915 World Series, which was the Philadelphia Phillies’ last playoff game until 1950, when Heintzelman himself started a World Series game for the team. Heintzelman may have fibbed about his age when he first signed as a professional; his card with the Howe Sports Bureau lists his birthdate in both 1916 and 1917, but not in the correct year of 1915.

Heintzelman was the second child and second son born to Alphonse and Mary Heintzelman. Alphonse was born in Germany and finished his formal education with the fifth grade, while Mary made it through the eighth grade. The 1940 census lists Alphonse’s profession as a “Caretaker” while Mary was listed as a “housekeeper.” Alphonse’s yearly salary was listed as $600, which equates to roughly $10,000 in 2015. Given the Heintzelmans’ education level, income, and the Depression era in which their boys were raised, it’s fair to suggest that the family struggled to get by.

After signing professionally with the Boston Braves in 1935, Heintzelman began his professional career with the McKeesport Braves of the Class-D Pennsylvania State Association. He appeared in 33 games and threw 195 innings, going 10-11 with an even 3.00 ERA as a 19-year-old.

Because of an oversight in the Braves’ front office, Heintzelman was lost to the Pittsburgh Pirates over the 1935-36 offseason. Despite the change in parent organization, he again found himself in the Pennsylvania State Association, this time for the Jeannette Little Pirates. The 20-year-old did even better in Jeannette, pitching to a 20-7 record with a nearly identical 3.07 ERA. He lowered his WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) and issued the same number of walks as in the 1935 season despite throwing an additional 48 innings.

Dubbed “Cannonball” because of the speed on his fastball, Heintzelman again put in a workmanlike 200 innings in 1937, pitching most of the season for the Knoxville Smokies of the Class A1 Southern Association, winning only 4 of 20 decisions in 198 innings of work. But the Pirates saw promise because on the last day of the major-league season they summoned Heintzelman to Forbes Field to pitch the first game of a season-ending doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds. Heintzelman went the distance, allowing six hits and three runs (two earned) in nine innings while picking up the win in the Pirates’ 4-3 triumph. He also scored two of the four Pirates’ runs in the process. The Pirates swept the doubleheader and ended the year on a 10-game winning streak.

The next year Heintzelman returned to Montreal, where he had worked in three 1937 games, for the majority of the season, posting an unsightly 5.48 ERA. He once again made one major-league appearance, pitching two innings in a May game against the New York Giants.

In 1939 Heintzelman appeared exclusively in the major leagues. He went 1-1 with a 5.05 ERA for the Pirates and logged only 35⅔ innings in 17 appearances. He was used so little that he actually retained his rookie status for the 1940 season.

At the turn of the new decade Heintzelman began to see regular time in the Pittsburgh rotation. From 1940 to 1942 he was consistent, if not average. He made 101 appearances, including 58 starts, and went 27-30 with a 4.09 ERA while averaging 164 innings per season. He did record seven shutouts over this period.

On May 24, 1941, right in the middle of the season, the 25-year old Heintzelman tied the knot with 22-year-old Pearl Boenker. Three days earlier he had started on the hill against the Boston Braves, faced only four batters and saw them all score. Perhaps marital jitters gave way to a new comfort at home that allowed for more success on the field. A month later, from June 30 through July 21, he rattled off five consecutive victories, part of a six-start stretch in which he pitched at least 8⅔ innings in each game.

In the spring of 1943, with America deep into war in Europe and the Pacific, Heintzelman himself became part of the war effort. He entered the US Army at the Jefferson Barracks in Missouri in March, and spent his time serving with the 65th Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized) of the 65th Infantry Division. The division served in Europe, reaching Austria in the spring of 1945.

Heintzelman performed various duties with the Army in Europe, spending time as a driver, radio operator, car commander, and mortar gunner. His memories of the war suggest that he was deep into heavy fighting. He recalled, “I shot my share of Germans. How many, I don’t know. I didn’t bother trying to keep score. It was too dangerous.”1

While Heintzelman, like many major leaguers, missed all of the 1943, ’44, and ’45 seasons, he did play baseball while in the military. Once the fighting ended in Europe, Heintzelman played for the 65th Infantry baseball team, starting around June of 1945.

“We had to wait for most of our baseball equipment, and until it arrived, we had a German cobbler make our shoes and we fixed our own spikes out of steel,” he remembered. “The fields weren’t in such good shape. We could have used an expert groundskeeper. But I did find plenty of baseball interest. All the fellows wanted to talk baseball and I took a lot of ribbing, especially from Pirate fans from Pittsburgh.”2

Heintzelman ended up playing for the 71st Infantry Red Circlers, made up primarily of professional players, in the 1945 ETO (European Theater) World Series. The games unfolded in front of crowds as large as 50,000 at Soldiers Field in Nuremberg, Germany, in September.

The next month Heintzelman was an instructor at a youth baseball clinic in Augsburg, Germany, sponsored by the 71st Division newspaper. The week-long clinic, which also featured Ewell Blackwell and Harry Walker as instructors, drew more than 350 German boys 8 to 15 years old.

Heintzelman was back in the United States and back with the Pirates for the beginning of the 1946 season. His military service gave him a better perspective on life at home. “I had a good experience pitching for Army teams,” he recalled. “My Army service did something to me. I know I have more confidence in myself now. Another thing. If I ever did any complaining, I’ll never do it again. Nobody had it too tough over here [in the United States during the war]. I remember one trip of 350 miles we took over in France. It took us two days and two nights. A bus ride over these roads in the United States (would) be a real pleasure now.”3

Back with the Pirates, Heintzelman returned to his previous form, going 8-12 with a 3.77 ERA. His best game of the season was a four-hit shutout of the Cubs at Wrigley Field on July 2, his only shutout of the season.

After making two appearances for the Pirates in early 1947, the 31-year-old Heintzelman was shipped from western Pennsylvania to the eastern part of the state, sold to the Phillies in early May. Heintzelman’s time in Pittsburgh was the epitome of average, a 37-43 record with a 4.14 ERA in parts of eight seasons. (It might have been better if he hadn’t missed his age 27 through 29 seasons — right in his athletic prime — while in the Army. “I was kind of enthused about joining the Phillies,” Heintzelman recalled. “Pittsburgh was rebuilding and I probably wasn’t in their plans.”4

Coming to Philadelphia from Pittsburgh, Heintzelman had never sniffed much of a pennant race, and he wouldn’t his first two years with the Phillies either. The team finished seventh in 1947 and sixth in 1948 as Heintzelman went 7-10 and 6-11 respectively. In 1949 the Phillies finished 81-73, good for third in the National League. They boasted several good-looking young players, including a pair of 22-year-old future Hall of Famers in center fielder Richie Ashburn and right-handed pitcher Robin Roberts (who referred to Heintzelman as “Goober” throughout his book on the Whiz Kids).

Perhaps the best player on the ’49 Phillies, Heintzelman had his best season in the majors. He led the team with 17 wins and a 3.02 ERA, and his five shutouts led the National League. He posted career highs in every significant pitching statistic aside from strikeouts. In mid-July Heintzelman boasted a 12-3 record and did not allow a run over 33 consecutive innings. He made a strong case for the National League All-Star team, but was left off by manager Billy Southworth of the Braves. “I was sore and disappointed at first, but I got over it in a hurry,” he said of the All-Star snub. “You don’t win ball games staying mad.”5

Why would a 33-year old pitcher who had never posted a winning record in the majors suddenly turn into one of the best pitchers in the league? Heintzelman credited Phils pitching coach George Earnshaw with suggesting during spring training that he speed up his delivery.6 Phillies fans voted him the team’s MVP for the season.7

Just as quickly as Heintzelman’s success appeared in 1949, it disappeared in 1950. His performance and statistics reverted to their pre-1949 form as if the success he had found had never happened. Heintzelman was pulled from the rotation after a 1-8 start, and finished the 1950 season with a dismal 3-9 record. His ERA jumped more than a run to 4.09, and he pitched only 125⅓ innings, half of what he had thrown in his stellar 1949 campaign.

While Heintzelman struggled, the team as a whole reached heights unseen in 35 years, winning the pennant with a 91-63 record, two games ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers. As Heintzelman faded to the background, the team was led by young players all over the diamond. The top five starting pitchers were all 26 or younger, and many of the position players were similarly youthful. The Phils’ youth led to them being dubbed the Whiz Kids.

Late in the 1950 season, with war in Korea heating up, the Phillies’ 21-year-old left-handed pitcher Curt Simmons was called up to active military duty. Simmons had been the Phillies’ second best pitcher in ’50 after Robin Roberts, and his absence threw the pitching rotation into flux. In a game on September 15 Bubba Church was nailed in the face by a line drive off the bat of the Cincinnati Reds’ Ted Kluszewski, knocking him from the game and effectively ending his season. Philadelphia manager Eddie Sawyer turned to Heintzelman, who allowed only one run in 6⅓ innings of relief to record only his second win of the year.

Then on September 25, with the team’s pitching staff depleted, Sawyer started Heintzelman in the first game of a crucial doubleheader against the Braves in Boston. The Braves started their ace Warren Spahn, who had won 21 games as opposed to Heintzelman’s two. But the Phillies knocked Spahn out of the box in the first inning, enabling Heintzelman to breeze to a complete-game 12-4 win.

In Game One of the World Series against the Yankees, the Phillies started their relief ace, Jim Konstanty, before going to Robin Roberts in Game Two. Perhaps with no better options, manager Eddie Sawyer sent Heintzelman to the Yankee Stadium mound for Game Three. He responded to his first (and only) postseason assignment with one of his best outings of the year, holding the Yankees to one earned run through 7⅔ innings. In the bottom of the eighth inning, with the Phillies leading 2-1, Heintzelman got two outs before suddenly losing command and walking the bases loaded. He gave way to Konstanty. The next batter reached on an error by shortstop Granny Hamner that tied the score. The Yankees pushed across the winning run in the bottom of the ninth and, one day later, swept the Series.

Heintzelman pitched two more nondescript years for the Phillies, going 6-12 in 1951 and 1-3 in 1952. He spent three additional seasons pitching for the Baltimore Orioles and Richmond Virginians in the International League before calling it a career after the 1955 season. He finished his major-league career with a record of 77-98 and a 3.98 ERA in just over 1,500 innings.

After his baseball career ended, Heintzelman returned to his native Missouri and worked for McDonnell-Douglas as an expediter before retiring in 1980.8 His son, Tom Heintzelman, played parts of four seasons as a utility infielder with the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants between 1973 and 1978. Ken Heintzelman died at 84 on August 14, 2000, in St. Peters, Missouri, and was buried in All Saints Cemetery in St. Peters.

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Ancestry.com, The Sporting News, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Special thanks to Bob Brady, Rod Nelson, and Bill Nowlin for their assistance in researching aspects of Ken Heintzelman’s life and career.

Notes

1 Gary Bedingfield, “Ken Heintzelman,” baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/heintzelman_ken.htm.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 57.

5 “Ken Heintzelman Improves With Age; He’s Young at 33,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 21, 1949.

6 Ibid.

7 Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 189.

8 Roberts and Rogers, 57.

Full Name

Kenneth Alphonse Heintzelman

Born

October 14, 1915 at Peruque, MO (USA)

Died

August 14, 2000 at St. Peters, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.