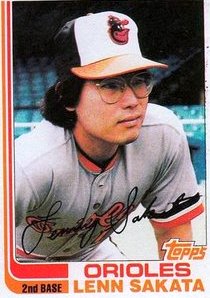

Lenn Sakata

The little Hawaiian with the big round glasses had good hands and range, plus just enough pop in his bat to play during 11 major-league seasons. A second baseman by trade, Lenn Sakata also saw a good bit of action at shortstop. It is often noted that in May 1982, he was the last Baltimore Oriole to play the position before Cal Ripken, Jr. was shifted over from third base for the bulk of his Iron Man run. Less well remembered, though, is that Earl Weaver trusted Lenn to take over for the finest-fielding shortstop in O’s history, Mark Belanger. It’s not surprising that with his steady personality and exposure to “The Oriole Way,” Sakata became a well-regarded manager who emphasized teaching.

The little Hawaiian with the big round glasses had good hands and range, plus just enough pop in his bat to play during 11 major-league seasons. A second baseman by trade, Lenn Sakata also saw a good bit of action at shortstop. It is often noted that in May 1982, he was the last Baltimore Oriole to play the position before Cal Ripken, Jr. was shifted over from third base for the bulk of his Iron Man run. Less well remembered, though, is that Earl Weaver trusted Lenn to take over for the finest-fielding shortstop in O’s history, Mark Belanger. It’s not surprising that with his steady personality and exposure to “The Oriole Way,” Sakata became a well-regarded manager who emphasized teaching.

Lenn Haruki Sakata was born in Honolulu on June 8, 1954. He is a fourth-generation American on his father’s side. Haruki “Melvin” Sakata (1924-1977) fought in World War II with the 442nd Infantry Regiment.[1] The highly decorated “Go for Broke” unit, as members labeled themselves, was made up of Japanese-Americans from Hawaii and the mainland. The regiment’s most famous veteran is U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye, who lost his arm amid the feats that won him a Medal of Honor. Private First Class Sakata served with Battery C of the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion — the men who liberated the Dachau concentration camp, among other exploits. In their leisure time, the artillerymen also formed a strong baseball team.

Lenn’s mother, Margaret Daishi Sakata, is a Nisei: her mother was born in Niigata, Japan.[2] The boy had an early baseball hero to root for — his maternal aunt Lillian’s husband, Jack Ladra, played in the Three-I League (Class B) in 1956-57. Jack then became one of the early Americans to play in Japan; the outfielder was with the Toei Flyers from 1958 through 1964.

Hawaii has long had a thriving baseball culture. Even so, only three men from the 50th state made it to the major leagues from 1914 to 1966. The last of them was Hank Oana, who enjoyed his final cup of coffee in 1945. When Lenn was a young boy, however, a good few Hawaiian pros besides Jack Ladra were playing in Japan. They were led by the pioneer, Wally Yonamine. Then in September 1967, just after Sakata went to Kalani High School, Mike Lum joined the Atlanta Braves. Another Honolulu native, John Matias, made the Chicago White Sox in 1970. That year, Kalani won the state championship with Lenn at short and Ryan Kurosaki on the pitching staff. Kurosaki, two years older, pitched in seven games for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1975.

After graduating from high school in 1971, Sakata attended Treasure Valley Community College in Ontario, Oregon. In June 1972, the San Francisco Giants drafted him in the 14th round, but he decided to stay in school. He transferred to Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. The Jesuit school is best known in sporting circles for basketball, especially as the alma mater of all-time great NBA point guard John Stockton, but it has turned out a sprinkling of big-league baseball players over the years. The most notable is Jason Bay, but two of Sakata’s teammates also made the majors, catcher Rick Sweet and outfielder Casey Parsons.

Lenn set a variety of team records, including home runs. He was a second-team All-American in 1974, leading the Bulldogs to the Big Sky Conference championship during his junior year with a batting line of .379-11-67. Ryan Kurosaki, who worked out with his friend in the winters, said that “Lenny was a good athlete, an exceptional golfer, but when he went to college, he got stronger and faster. I couldn’t believe how much. The work ethic and the competition really elevated his play.”

From 1971 to 1974, Sakata also played with a Japanese-Hawaiian institution, the Asahi ballclub. Jack Ladra brought him to the team, which was originally formed in 1905. When Lenn was on the team, it practiced “small ball,” which he said “reminded me on how to play the game.”[3]

Pro scouts remained interested in Sakata. The San Diego Padres selected him in the fifth round of the draft in June 1974; again he did not sign. Then, in the secondary phase of the draft in January 1975, the Milwaukee Brewers decided to make the infielder their number 1 pick (10th overall). This time Lenn did turn pro — amid some controversy.

Gonzaga coach Larry Koentopp stated that two Brewers scouts, Dick Bogard and Roland Leblanc, along with farm director Tony Siegle, pressured Sakata in an airport meeting on January 19. “I was extremely displeased with the way Milwaukee had gone about it. . . . He’d been hot-boxed.” Koentopp said Sakata had asked Milwaukee to release him from his contract, but was refused. He said it was decided that it would take too long to go through the courts seeking Sakata’s reinstatement as a college player.[4]

It was interesting to note the local spin that different papers put on the wire-service report. Whereas the Idaho State Journal, which covers Gonzaga sports, gave only Coach Koentopp’s side of the story, the Wisconsin papers provided some or all of Tony Siegle’s rebuttal. For example: “We did everything by the rules and the coach, obviously upset at losing him, is pouring a little kerosene on the fire.”[5]

At any rate, Lenn took the $10,000 he got for signing and reported to Thetford Mines, Quebec, in the Eastern League. (His contract specified that he would start at the Double-A level.) This town of roughly 20,000, whose economy was based on asbestos into the 1980s, is in the rural Chaudière-Appalaches region between Québec City and northwestern Maine. It really wasn’t ready even for Double-A ball, as depicted in Frank Dolson’s 1982 book Beating the Bushes. Yet despite playing before home crowds that averaged 200 to 300, Sakata became the Eastern League’s All-Star second baseman in 1975. His hitting was not remarkable (.257, with 9 homers and 43 RBIs), but he made a strong all-around impression.

Lenn moved up to Triple-A in ’76 — returning to Spokane. Breaking in as a pro manager that year was Frank Howard. The 6-foot-8, 280-pound “Hondo” was the Mark McGwire of his day, so it carried real meaning when he called Sakata “the strongest player in our system.”[6] He hit well (.280-10-70), but Indians player-coach Tommie Reynolds added, “He’s made some unbelievable plays. … Lenny’s made the difference.”[7]

After an even stronger start at Spokane in 1977 (.304-4-73) — spurred by the passing of his father in spring training[8] — Sakata made his major-league debut that July. He got 154 at-bats for the Brewers over the second half of the season. The rookie — still wearing braces on his teeth — impressed with his dexterity around the bag and his spectacular plays.[9] One standout was a sprinting, diving stop followed by a somersault and hook-shot throw to nip the runner. He only batted .162-2-12, though, as he had to contend with a couple of problems. “Manager Alex Grammas considered Sakata a showboat who tended to sulk and loaf, and a pulled groin muscle further hampered Sakata when he joined the Brewers.”[10] However, the Asian didn’t let the ethnic slurs of knucklehead fans get to him (except once when he gave the Baltimore crowd the finger).[11]

George Bamberger replaced Grammas in ’78, and Lenn was awarded the second-base job coming out of spring training. But he soon found himself riding the shuttle between Milwaukee (.192-0-3) and Spokane (.269-0-20). “What happened, of course, was the Robin Yount–Paul Molitor story. Yount took the first month of the season to make career decisions — baseball beat golf at the wire — and Molitor, a rookie, started at shortstop. But when Yount came back, Molitor was hitting over .300 and something had to give.”[12]

Sakata played just 30 big-league games in 1978 and a mere 4 in 1979 (he went .300-6-64 at Triple-A Vancouver). In addition to Molitor, he found himself behind power-hitting veteran utilityman Don Money and Milwaukee’s second sacker of the future, Jim Gantner. Spokane manager John Felske (who, like Gantner, had also been at Thetford Mines) noted, “He has a tendency to get down on himself. . . .he expects perfection, and he hasn’t learned that he can’t be perfect all the time.”[13] Lenn sought a trade, and it was granted, as the Orioles acquired him in December 1979 for marginal pitcher John Flinn.

Sakata didn’t make the big team in 1980, and at first he balked at reporting to Triple-A Rochester. After he was recalled in late May, the infielder still didn’t see that much action with Baltimore (.193-1-9 in 43 games). Yet he slowly began to gain Earl Weaver’s confidence. Sakata had also worked on his perceived liability, a weak stick. “I call him Mighty Mouse,” said trainer Ralph Salvon. “Lenny’s got the biggest biceps on the team except maybe for Ken Singleton.”[14] Daniel Okrent, who put a 1982 game between Milwaukee and Baltimore under the microscope in his book Nine Innings, described him wryly:

“Sakata was one of the shortest players in the majors, listed in the Baltimore press guide at 5’9” but at least a full inch shorter. He was also distinguished as one of the first major leaguers to turn to the Nautilus machine as a strength builder; standing next to a taller teammate, like the elongated Jim Palmer, Sakata’s overdeveloped chest and shoulders gave him the appearance of a midget wrestler.”[15]

Lenn seemed to save his best for his old club. He had his first and only two-homer game at any level against the Brewers on September 20, 1981, and in the game Okrent analyzed (June 10, 1982), he ripped a leadoff homer. “There’s a little extra incentive for me against Milwaukee. I don’t feel hatred, but I like to prove I can play and gain their respect. They said I didn’t have the ability to play for their team. I didn’t feel I got a chance,” he said.[16]

He never felt entirely comfortable out of his natural position, but Sakata concentrated on developing his footwork and arm strength at short.[17] He bought Cal Ripken time to get acclimated. The 1982 campaign was easily Lenn’s best, as he posted career highs in nearly every major category (.259-6-31). He remained a useful reserve in 1983 (.254-3-12), even serving as an emergency catcher in one game on August 24. The Toronto Blue Jays thought they had free rein on the bases, but Orioles reliever Tippy Martinez picked off three straight runners at first in the top of the 10th inning, then Sakata — who hadn’t caught since Little League — then won it with a three-run homer in the bottom.

Although Lenn did not see action in the AL playoffs against the White Sox, he did appear in one game of the World Series against the Phillies — Baltimore’s last championship to date. It was the first appearance by a Hawaiian player in the Series.

During 1984 and 1985, Sakata continued to back up Rich Dauer at second. After the 1984 season, the Orioles toured Japan. Watching every game on TV was a 15-year-old Japanese boy named So Taguchi, who drew inspiration from Lenn and went on to a long career both at home and in the majors.[18]

The Orioles demoted Lenn to Rochester in ’85, something the veteran did not have to accept. He decided to go, but when the Orioles did not offer him a contract for the next year, he signed with Oakland. Lenn spent the bulk of the year at Triple-A Tacoma, playing 17 games with the A’s late in the season. The A’s did not ask him back either, but Sakata hooked on with the Yankees as a backup. His big-league career ended on June 28, 1987, though, when he tore ligaments in an ankle sliding back into second on a pickoff play. Teammate Ron Kittle, one of the men who carried Lenn from the field on a stretcher, wound up on the 15-day disabled list because he pulled a muscle in his neck.[19]

After his ankle recovered, Lenn played briefly for Columbus on a rehab assignment. The Yankees restored him to the active roster that September, but he saw no action and was released in November.

Sakata then began the second phase of his life in baseball: coaching and managing. He rejoined the A’s organization in 1988, winning honors as Northwest League Manager of the Year with Southern Oregon, representing Medford, Oregon. He remained in the Oakland chain through 1990. Lenn managed Modesto in the California League through June 1989, but when the club struggled, he was reassigned to a post as roving infield instructor.

Incidentally, he wasn’t quite through as a player. In the fall and winter of 1990, Sakata played for the San Bernardino Pride of the Senior Professional Baseball Association. He played in 15 of the team’s 25 games (.327-2-10), but the league then folded.

Lenn then moved on to the California Angels, where he spent four summers with their minor leaguers. He was a coach at Edmonton in 1991-1992 and Vancouver in 1993-94. It was in the latter post where he met his second wife, Shane. A native of Vancouver, she was working in the club’s front office. Lenn and Shane were married in 1995[20] (he has a daughter named Erin from his previous marriage).

The Hawaiian also welcomed an opportunity to promote the game back in the islands. When the Hawaii Winter League (HWL) began operations in 1993, he was on hand as manager of his hometown Honolulu Sharks.

In 1995, however, Sakata took “an offer I couldn’t refuse” to coach in Japan, serving under Bobby Valentine with the Chiba Lotte Marines. He stayed there four years, managing the Marines’ minor-league team his first season, coaching on the big-league team for the next two, and coaching again at the minor-league level the last year. “We finished last my final two years there and they decided they didn’t want me back. I was finally fired because I complained too much,” He said. Although he enjoyed the experience overall, Lenn took issue with the rigidity of the old guard, including their resistance to weight training. He didn’t even get a chance to learn Japanese, being assigned an interpreter.[21]

Upon his return from Japan in 1999, Sakata took a position with the San Francisco Giants, choosing them over the Brewers and Seattle Mariners on the recommendation of HWL president Duane Kurisu.[22] Lenn managed the Class A San José Giants, leading them to the final game of the California League championship. He then moved to the other Class A club, the Bakersfield Blaze, for the 2000 season. “The Giants philosophy is to move people around,” observed Blaze GM Jack Patton, adding that “Lenn is a quiet gentleman who obviously has managerial ability.”

Sakata returned to the South Bay to manage San José again in 2001. Following that season, Les Murakami, the longtime baseball coach at the University of Hawaii, stepped down. Of the search for his replacement, Murakami said, “I was never on the selection committee, but the perfect guy is Lenn Sakata. But unfortunately, he doesn’t have a (college) degree. I really think he was everybody’s first choice.”[23]

Instead, in January 2002, Lenn vaulted to the Triple-A ranks, as the Giants named him to manage their top farm club, the Fresno Grizzlies of the Pacific Coast League. The team finished 57-87, though, and the organization made him a roving instructor. After 2003, Sakata skippered San José for another four years. He became the winningest manager in the California League’s history.

Sakata also continues to give back to his original baseball community. In 2006, when Hawaii Winter Baseball resumed after a nine-year hiatus, he managed the Waikiki BeachBoys. That summer, cup-of-coffee major leaguer Chad Santos from Honolulu also expressed his gratitude to Lenn, who “returns to his native state every winter and spends much of his time tutoring high schoolers and other young players on a fenceless field in the town of Kahala.”[24]

Sakata and others felt that he should have gotten more consideration for bigger jobs. Still, for most of this time, he was philosophical about his assignment in the lower levels. In July 2007, he commented:

“I think all minor-league baseball jobs are lateral moves. There’s no stigma being a one-A coach as opposed to Triple-A because the game has changed. There’s no natural progression. People get major-league jobs with no coaching experience, straight from the broadcast booth.

“I don’t look at this as a career deprecating thing for me. It’s one of those situations where this is where I can have the best impact. The players are eager and more impressionable. I feel fulfilled at this level, although maybe yes, I’ve been at this level much too long.”[25]

Ultimately, though, Lenn decided it was time for a move. In November 2007, he agreed to rejoin Chiba Lotte and manage their farm team (ni-gun in Japanese) once more. The move reunited him with Bobby Valentine, who became a hero with the Marines as manager of the 2005 Japan Series champions. Sakata said, “It’s a hard thing to let go, but I still felt that my time had come. I was not going to move any higher than I was. I was always going to be a minor leaguer. I would’ve at least liked to have been asked to interview for a job or be considered for a major-league job.”[26]

However, Lenn does take pride in the advancement of another Japanese-American manager, Don Wakamatsu. When Wakamatsu got the top job with the Seattle Mariners in November 2008, Sakata — Don’s boyhood hero — said, “That’s a milestone — a barrier-breaker, if you will. I think Asian-Americans will probably stand up and be very proud of the fact somebody finally got to that position in baseball.”[27]

Sakata did not plan to return to the Marines after the 2009 season, and neither did Valentine.[28] In 2007, though, Bobby V said it best about Sakata’s career, now and to come. “Lenn Sakata, in my mind, has always been one of the great baseball guys. He’s dedicated his life to where he’s played it, learned it, and can teach it. He’s exactly what my organization needs: To have someone with his credentials, enthusiasm, and knowledge of the game.”[29]

Sources

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0.

Haruki Sakata’s unit and rank:

http://www.idreamof.com/military/ww2/sa-she_surnames.htm

http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/resources/military/11053/

http://www.goforbroke.org/history/history_historical_veterans_522nd.asp

[1] Chapman, Lou. “Sakata Sharp as Brewer Keystoner.” The Sporting News, August 27, 1977: 16.

[2] Obituaries, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, April 13, 2006.

[3] Ohira, Rod. “‘Every kid’s dream’: To play for Asahi”. The Honolulu Advertiser, November 7, 2005.

[4] “G.U. Baseball Mentor Raps Method Used to Sign Sakata,” Idaho State Journal, January 28, 1975: 6.

[5] “University Coach Charges Brewers Pressured Signing,” Sheboygan Journal, January 28, 1975: 8.

[6] “Brewer Kids Rate Raves,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1977: 18.

[7] “Sakata Receives Credit for Triple-A Turnabout,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1976: 33.

[8] Reardon, Dave. “World Series winner not good enough for UH.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, April 1, 2001.

[9] The Sporting News, September 10, 1977: 23.

[10] “Brewers’ Sakata Is Pleasant Problem,” The Associated Press, April 16, 1978.

[11] Chapman, op. cit.

[12] Gonring, Mike. “Sakata Has Bags, Eyes Brewer Travel Guide.” The Sporting News, March 24, 1979: 48.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ken Nigro, “Sakata Mighty as O’s Shortstop.” The Sporting News, October 10, 1981: 28.

[15] Okrent, Daniel. Nine Innings. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1985: 10.

[16] Nigro, op. cit.

[17] Nigro, Ken. “Pressure on Sakata, O’s New Shortstop.” The Sporting News, March 20, 1982: 34.

[18] Wood, Ben. “Sakata’s play inspired Japan’s Taguchi to shoot for majors.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 9, 2006.

[19] Conner, Floyd. Baseball’s Most Wanted II. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s Inc, 2003: 226.

[20] “Managing to Succeed — Sakata, a Small Player Who Made It Big, Teaches S.J. Giants.” San Jose Mercury News, August 13, 1999: 1D.

[21] Chase, Al. “Good to Be Back.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 5, 1999.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ohira, Rod. “Murakami reaches out to reassure fellow coach.” Honolulu Advertiser, February 25, 2001.

[24] Baggarly, Andrew. “Santos’ long wait pays off.” Marin Independent Journal, July 18, 2006: D5.

[25] Reardon, Dave. “Sakata a Giant in San José.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 31, 2007.

[26] Kaneshiro, Stacy. “Sakata to manage Chiba’s farm team.” Honolulu Advertiser, November 8, 2007.

[27] Stone, Larry. “Mariners are making changes to believe in.” Seattle Times, November 23, 2008.

[28] Kaneshiro, Stacy. “17th pro season for Benny.” Honolulu Advertiser, January 22, 2009.

[29] Kaneshiro, Stacy. “Sakata Heads To Japan.” www.baseballamerica.com, November 13, 2007.

Full Name

Lenn Haruki Sakata

Born

June 8, 1954 at Honolulu, HI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.