Mike Mowrey

Contemporary observers considered Mike Mowrey one of the best third basemen in baseball. A lifetime .256 hitter with a reputation for being particularly dangerous in the pinches, Mowrey was best known for his unorthodox fielding style—instead of catching a hard smash in his glove, he would knock the ball to the ground and then pick it up to throw out the runner. Defending against the bunt was a corner infielder’s primary responsibility during the Deadball Era, and in that aspect of his duties the 5′ 9″, 160-lb. redhead excelled. In 1910 Alfred H. Spink called Mowrey “the best fielder of bunts in either league.”

Contemporary observers considered Mike Mowrey one of the best third basemen in baseball. A lifetime .256 hitter with a reputation for being particularly dangerous in the pinches, Mowrey was best known for his unorthodox fielding style—instead of catching a hard smash in his glove, he would knock the ball to the ground and then pick it up to throw out the runner. Defending against the bunt was a corner infielder’s primary responsibility during the Deadball Era, and in that aspect of his duties the 5′ 9″, 160-lb. redhead excelled. In 1910 Alfred H. Spink called Mowrey “the best fielder of bunts in either league.”

Jacob Mowrey’s fourth son, Harry Harlan Mowrey, was born on March 24, 1883, near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, a town of 7,000 citizens situated just above the Mason-Dixon Line. Less than 20 years earlier the town had been torched by Confederate General John McCausland, but by 1883 it was a hotbed of baseball activity. Town historians claim that the first night game in history occurred on May 16, 1883, opposite the Chambersburg train station, with the lights placed on railroad cars. Like many railroad towns, Chambersburg had a problem with hobos. Jacob Mowrey, the town’s sheriff, frequently housed tramps in his jail cell overnight. Young Harry became particularly friendly with one tramp, prompting one of his brothers to nickname him “Mike the Hobo.” Obviously the name stuck.

Mike grew up playing baseball with school and town teams in the Chambersburg area. By the turn of the century he was a husky third baseman for Chambersburg Academy, playing well enough in 1902 to earn a shot with an independent team from Chester, Pennsylvania, just south of Philadelphia. Mike returned to central Pennsylvania with Williamsport of the outlaw Tri-State League in 1904, the same year he married Nannie K. Hammel (the couple remained married until his death 43 years later). In 1905 the 22-year-old Mowrey finally joined the ranks of Organized Baseball with Savannah of the South Atlantic League. His .285 batting average and flashy defensive play at third base so impressed the Cincinnati Reds that they purchased his contract.

Mike made his big-league debut on September 24, 1905, playing both ends of a doubleheader. In total he appeared in seven games during his late-season tryout, batting .267 but making seven errors at third base. That off-season the Chicago Cubs reportedly tried to acquire Mowrey from the Reds but wound up with veteran Harry Steinfeldt instead. Steinfeldt went on to lead the Cubs in batting average in 1906 and become a key member of one of the greatest clubs of all time. Mowrey, meanwhile, spent most of 1906 on loan to Baltimore of the Eastern League, which was owned by Cincinnati manager Ned Hanlon. The Reds recalled him in August to avoid losing him in the minor-league draft, and Mike hit a robust .321 in 21 games to give him the inside track on a starting position for 1907.

That year Mowrey did win the regular third-base job in Cincinnati, playing in 138 games and hitting .252, a comfortable nine points above the league average. He also slugged the first of his seven lifetime home runs, an inside-the-park job against Joe McGinnity on August 14. Mike regressed in 1908, however, hitting only .220 and losing his starting position to Hans Lobert. He hurt his knee in 1909 and was hitting just .191 when the Reds traded him to St. Louis on August 22 for infielder Chappy Charles. Returning to regular duty with the Cardinals in 1910, Mowrey enjoyed the best season of his 13-year career, hitting .282 (26 points over the NL average) with two home runs, a career-high 70 RBIs, and 21 stolen bases. He remained the Cardinals’ regular third baseman through the end of 1913, collecting at least 400 at-bats each year and hitting between .255 and .268.

During the 1913 season George Stallings tried to acquire Mowrey for the Braves. When asked by Cards manager Miller Huggins if he wanted to go to Boston, Mike replied that he preferred to stay in St. Louis rather than uproot his family, though he had no objection to moving there after the season. Instead the Cardinals sent him to the Pirates on December 12, 1913, in a blockbuster trade that became known as the “famous three-for-five deal.” St. Louis traded Mike, first-baseman Ed Konetchy, and pitcher Bob Harmon to Pittsburgh for infielders Jack Miller and Art Butler, outfielders Owen Wilson and Cozy Dolan, and pitcher Hank Robinson. Hampered by injuries, Mowrey played in only 79 games for the Pirates before drawing his unconditional release. He played with some independent teams to finish out the 1914 season.

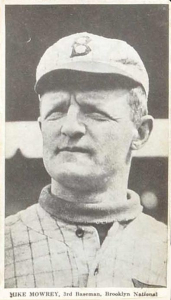

In 1915 Mowrey remained in Pittsburgh with the Federal League’s Stogies, hitting .280 and leading all Fed third basemen with a .959 fielding percentage. He also established career highs in games (151), hits (146), and stolen bases (40), ranking second in the FL in the latter category. After the Feds folded, Wilbert Robinson signed Mowrey for his veteran team in Brooklyn. In a photo from 1916, Mike’s mashed nose and the lines in his unsmiling face create the perfect image of an experienced veteran of the Deadball wars. That year he batted .244 without a single home run in 144 games, but his career-best .965 fielding percentage led NL third basemen and the Robins won the pennant. Appearing in his first World Series, Mike hit a paltry .176 in Brooklyn’s losing effort.

In 1917 the 33-year-old third baseman held out for more money, not reporting until April 10. Whether he wasn’t prepared or he suddenly got old, Mowrey batted just .214 (his worst average since his abysmal 1909) and the Robins released him in August. At that point he joined the war effort, working in a steel plant and playing ball in the Bethlehem Steel League alongside many other ex-professionals.

After the war Mike became a player-manager for minor-league teams in the Chambersburg area. In 1920 he batted .342 and led the Hagerstown Hubs to the championship of the newly organized Blue Ridge League. Hagerstown fell to the cellar the following season and in 1922 Mike managed his hometown club in the same league. Though he batted .351 in the 75 games he played, Chambersburg finished next to last. Mowrey also managed Rochester in the International League and Scottdale, Pennsylvania, in the Middle Atlantic League, but at some point during the 1920s he got fed up with professional baseball and returned to Chambersburg.

Mowrey lived there for the rest of his life. He bought some farmland and supplemented his farm income by working as a night watchman at Wilson College. During World War II Mike worked at the Letterkenny Ordnance Depot and coached its baseball team. He passed away from heart disease on March 20, 1947. Two months later, over 1,000 people attended a memorial service for Mike held at Henninger Field after a Letterkenny game. According to the eulogy, “He was our Grand Old Man of Baseball, who started as a sandlotter and went to the top in baseball to become one of the greatest third basemen the game had known.”

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Harry Harlan Mowrey

Born

March 24, 1884 at Brown's Mill, PA (USA)

Died

March 20, 1947 at Chambersburg, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.