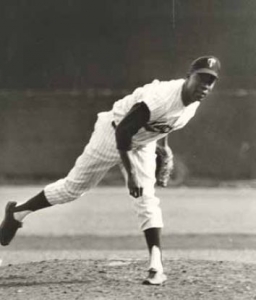

Mudcat Grant

The 1965 World Series moved to Metropolitan Stadium for Game Six. The Los Angeles Dodgers were holding a 3-2 series lead, and Walter Alston’s crew was looking to close out the Twins. Standing in the way of the championship was Minnesota ace Jim “Mudcat” Grant. Claude Osteen took the hill for the Dodgers. Grant, who had been suffering from a cold for weeks, was pitching on two days’ rest and felt much older than his 30 years. If there was any question about Grant’s ability while under the weather and working on short rest, those doubts were answered rather quickly, as Grant faced the minimum through four innings.

The 1965 World Series moved to Metropolitan Stadium for Game Six. The Los Angeles Dodgers were holding a 3-2 series lead, and Walter Alston’s crew was looking to close out the Twins. Standing in the way of the championship was Minnesota ace Jim “Mudcat” Grant. Claude Osteen took the hill for the Dodgers. Grant, who had been suffering from a cold for weeks, was pitching on two days’ rest and felt much older than his 30 years. If there was any question about Grant’s ability while under the weather and working on short rest, those doubts were answered rather quickly, as Grant faced the minimum through four innings.

With the Twins leading 2-0 in the bottom of the sixth, second baseman Frank Quilici was intentionally walked to bring Mudcat to the plate. Grant drilled a home run to left-center to give the Twins a 5-0 lead. He became just the second American League pitcher to hit a home run in a World Series. Mudcat forced a Game Seven by beating the Dodgers with his pitching and hitting. He went the distance, giving up one run on six hits, striking out five batters and walking none. “I really didn’t know how long I would go,” said Grant. “I just figured I’d go as long as I could for as hard as I could.”1 Mudcat got the Twins to the seventh game, but they fell short against Sandy Koufax, 2-0.

James Timothy Grant was born on August 13, 1935, in Lacoochee, Florida. Lacoochee, then a lumber town, is about 40 miles north of Tampa. He was one of seven children born to James and Viola Grant. Like many of the residents of Lacoochee, James Grant, Sr. worked at the lumber mill, but he died when Mudcat was two and the responsibility fell to Viola to provide for the family. She worked during the day at a citrus canning factory and took in domestic work as well.

Jim was a three-sport star (football, basketball, baseball) at Moore Academy in Dade City, Florida. He also competed on the semipro sandlots for the Lacoochee Nine Devils. Grant was mostly stationed at third base in those days because he had such a strong arm. He earned an athletic scholarship to Florida A&M University to play football and baseball.

Grant left Florida A&M during his sophomore year because of financial constraints on his family. He sought work to help out at home, saying, “Somebody had to start earning money and sacrifice.”2

Grant relocated to New Smyrna Beach, Florida, and found work as a carpenter’s helper while he lived with relatives. It was the keen eye of Cleveland Indians bird-dog scout Fred Merkle that started Grant on his way to life as a professional baseball player. Merkle worked the State Negro Baseball Tournament at Daytona Beach when Grant was a senior in high school, but Grant was only 17, too young to sign a contract. When Merkle heard that Grant had left Florida A&M, he tracked Mudcat down in Daytona Beach to sign him up with Cleveland.

The Indians held their minor-league camp in Daytona Beach and offered Grant a tryout. It was here that his moniker was bestowed upon him. “A guy named Leroy Bartow Irby saw me, decided I was from Mississippi and called me ‘Mudcat,’” recalled Grant. “I didn’t know him very well, and I didn’t pay attention to what he called me. The old Yankee pitcher Red Ruffing was the coach in charge of making the minor-league assignments. He read off names and the fields where the players were to report. The first day I heard him say ‘Mudcat Grant, field number two.’ I thought there was another Grant in camp, that I would be the last one standing there. I wouldn’t hear my name so I would just float around the different diamonds.”3

Grant straightened out the name confusion, but he would forever be known as Mudcat, a nickname that he came to embrace. He left Florida for the first time in his life, traveling to North Dakota to pitch for Cleveland’s Class C affiliate, Fargo-Moorhead of the Northern League. There were many cultural differences between Lacoochee and Fargo, most notably an absence of blacks living in Fargo. Although Fargo was not the segregated South, Grant still found racial bias.

But he didn’t let his new surroundings affect his pitching ability. After losing his first game of the season, Grant won 12 in a row. He was the league’s Rookie Pitcher of the Year, completing the season with a record of 21-5 and an ERA of 3.40. After a brilliant season at Class B Keokuk (Iowa) of the Three I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League in 1955, he landed at Reading of the Class A Eastern League, where he endured his first losing season in pro ball (12-13). That winter Grant played winter ball for the Willard Blues of the Colombian League, where he was voted unanimously as Player of the Year. His record was 9-7 including a no-hitter against Vanytor. Manager Don Heffner also played Grant at second base and the outfield between his starting assignments. Mudcat hit nine home runs to finish second in the league.

Grant was assigned to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League in 1957 and went 18-7 with a spectacular ERA of 2.32 and 178 strikeouts. “I’ve never seen a young pitcher come along as fast as he has,” said San Diego general manager Ralph Kiner. “He wants to learn and is willing to take advice. That is a big point in his favor.” Mudcat directed the credit to Padres pitching coach Vic Lombardi. “When I joined the Padres, Vic Lombardi took me in hand and taught me a lot,” he said. “When I make a mistake out there on the mound, Vic tells me so I won’t repeat it.”

Grant reached the major leagues with the Indians at the start of the 1958 season. Larry Doby was reacquired during the offseason from Baltimore, giving Grant an older black player to lean on, and Doby took him under his wing. “You figured because you made the majors, you now were on equal terms with the other guys. But that wasn’t the case,” said Grant.4 He started the third game of the year, winning his debut 3-2 over Kansas City. He went the distance, striking out five batters. He won two of his next three starts, sporting a 3-0 record with a 1.85 ERA, but leveled off and finished the year at 10-11. He struck out 111 batters, but walked 104. Grant’s lack of control would be a burden during his early years in Cleveland. After Joe Gordon took over as manager when Bobby Bragan was fired, Grant spent as much time relieving as starting. Cleveland finished in fourth place with a record of 77-76, closing out the year winning 13 of its final 18 contests.

Spurred on by such a strong finish, Indians fans greeted the 1959 season with high hopes. The Indians finished second in the AL behind the Go-Go White Sox, and Mudcat finished the year at 10-7 with an ERA of 4.14. Six of his 10 wins came against the Senators (he won all six decisions against Washington and was 11-0 all-time at Griffith Stadium), but he started less frequently than he did in 1958.

The next season was one to forget for Grant. For the second year in a row, he took the hill for 19 starts in 1960, posting a 9-8 record with a 4.40 ERA. He walked 78 batters and struck out 75. On September 5 Grant started in Detroit, pitched seven innings and struck out 10, but lost, 4-3. It was his career high for punchouts; he equaled it three more times.

The 1960 season ended early for Grant, and with a loud thud, the result of an ugly incident. On September 16 the Indians were at home getting ready to play the Kansas City Athletics. Before the game, as the National Anthem was being played, Grant got into an argument with bullpen coach (and Texas resident) Ted Wilks. “I was standing in the bullpen, singing along with the National Anthem as I always do,” Mudcat said. “When it got to that part ‘home of the brave and land of the free’ I sang something like ‘this land is not so free. I can’t even go to Mississippi.’ It was something like that and I sang it in fun. Wilks heard me and called me a (racial) name. I got so mad I couldn’t hold myself back. I told him that Texas is worse than Russia. Then I walked straight into the clubhouse.”5

Grant dressed and left the park without telling manager Jimmy Dykes, who had no idea what had happened. Dykes suspended Grant for the rest of the season without pay, which Grant accepted. “Jim called me after the game and told me he had made a big mistake,” said Dykes. “I said, ‘Yes you did and there’s nothing I can do about it now. The suspension sticks.’” Wilks apologized for his remarks, which Grant refused to acknowledge. “I’m sick of hearing remarks about colored people. I don’t have to stand there and take it,” said Grant.6 Wilks left the organization after the season.

With Dykes in charge, Grant finally found some stability in his career in 1961. Rather than shuttling him between the starting rotation and the bullpen, Dykes used Grant exclusively as a starter. Mudcat started 35 games and responded with his best season to date, leading the team in wins (15), complete games (11), innings pitched (244⅔), and shutouts (3), and was second in strikeouts (146). He won six straight starts from May 15 to June 7. “I figured this was my fourth year with the team and if I was going to have a good season, this should be it,” he said. “When did I realize that I had won a steady job? I still haven’t come to the point of saying to myself ‘I’m a starting pitcher.’ We fellows who are starting now can take nothing for granted. Some of those fellows in the bullpen can replace us.”7

“Grant is an entirely different pitcher now,” said his former manager, Joe Gordon, who managed Kansas City in 1961. “He concentrates on every pitch. He had to grow up. But not everybody grows up as fast as Mud did. Some of them have to reach 27 or so. What’s Grant, 25?”8

Just when things were going Grant’s way, he was told to report to active duty in the US Army on November 2, 1961. Grant reported for a year of duty at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where he pitched for and managed the base’s team. Grant was able to pitch on weekends with the Indians. He received a 30-day furlough and beat the Yankees, 7-1, on May 11, but developed a sore arm during that period. Grant was discharged from the Army early and rejoined the Indians for good in mid-July. He managed two 10-strikeout efforts in September, one a loss to Baltimore, the other a win against Los Angeles. He finished the season with a 7-10 record and a 4.27 ERA.

For the Indians, 1963 was a long season as they finished in fourth place, 25½ games behind New York. Mudcat finished with a record of 13-14 and an ERA of 3.69. He achieved his career high in strikeouts with 157, walked 87 and pitched 10 complete games.

For several offseasons, Grant had worked in the Indians ticket office. Now he was part of the Community Relations team, and he was in demand to speak at churches, businesses, and colleges. He made more than 100 public appearances in the offseason between 1963 and ’64. He also started a nightclub act, “Mudcat and the Kittens.” Grant, who was an accomplished singer with a voice he described as “somewhere between a baritone and a tenor,” fronted the group, which played in jazz clubs all over Cleveland and once appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

A bright spot for Jim and his wife, Lucile, known by most as Tiny, was the birth of their first son, James Timothy III. They later adopted another son, Rusty.

After getting got off to a rocky start in 1964, Grant found himself shipped to Minnesota for pitcher Lee Stange and infielder George Banks on June 15. “I’m sure this trade will help both ballclubs,” said Minnesota manager Sam Mele. “Grant is a good all-around man and we’ll use him as a starter. He’s been having his troubles and we hope he can straighten himself out.”9 Turn it around he did. With the Twins, Mudcat posted a record of 11-9 with a 2.82 ERA. He struck out more than twice as many as he walked and threw 10 complete games. He started July on a four-game winning streak, lowering his ERA from 3.86 to 2.62. The Indians and Twins finished the year with identical 79-83 records, 20 games off the pace.

In 1965 the Twins were embarking on their fifth season since relocating from Washington, and everything came together for them as they made their first appearance in the World Series. Trailing Cleveland by a half-game on June 30, the Twins went on a 22-9 run in July and never looked back, finishing with a record of 102-60, seven games ahead of Chicago.

Grant enjoyed his best season in the majors. His name was all over the AL statistical leader board at the end of the season as he led the league in wins (21) and shutouts (six), was second in complete games (14), and third in innings pitched (270⅓). He pitched in the All-Star Game on July 13 at Metropolitan Stadium. (Grant was on the 1963 squad but didn’t pitch.) The only downside was that Grant led the league with 34 home runs allowed. He was the leader of a pennant-winning staff in which no starter had an ERA over 3.50 (Grant 21-7, 3.30 ERA, Jim Kaat 18-11, 2.83, Jim Perry 12-7, 2.63, Camilo Pascual 9-3, 3.35). Mudcat was named The Sporting News American League Pitcher of the Year, and was the first black pitcher in the American League to win 20 games in a season, as well as the first black AL pitcher to win a game in the World Series.

What was the cause of Mudcat’s fine season? He claimed that he was the same pitcher in Minnesota as he had been in Cleveland, except that the Twins had the potential to score more runs to back him. But Mudcat also was quick to give credit to his new pitching coach, Johnny Sain. Sain, a great pitcher with the Boston Braves, taught Grant a new pitch. “It’s a fast curve,” said Grant. “Johnny Sain is teaching it to several of the guys. I’ve never had a real good fast curve before. I’ve always had a good fastball, a change of pace and a slow curve. They said I needed to change speeds. I’ve always been able to change off my fastball, throw a straight slow ball up there. But until this year, I never thought in terms of spinning the ball. That’s where Sain helped me.” Grant’s former batterymate in Cleveland, John Romano, noticed the difference, saying, “This isn’t the same Grant that I used to catch. He never had a curve when I caught him.”10

In 1966 the Twins were enthusiastic as they reported to spring training at Tinker Field in Orlando. Grant initially held out for a bigger contract, but eventually signed and reported to camp. He started the season poorly, posting a 5-12 record at the All-Star break with an ERA of 3.28. “Last year I pitched well enough in tough games until the late innings,” Mudcat said. “Then a lot of times our guys would come along and score. This year I’ve been pitching well until late innings and losing. I haven’t pitched as bad as my 5-12 record in the first half indicated. But maybe I can make it better by pitching better. I’m going to try.”11

After meeting with Mele and Sain at the break, Grant did turn himself around, going 8-1 the rest of the way. Despite his turnaround and Kaat’s 25 wins, the Twins could not catch Baltimore for the pennant. Kaat, who won the Gold Glove for a fifth time, said, “I’ve always had the reputation as a good fielder, but I think it’s a lot of publicity. I got a couple of Gold Glove Awards as the best-fielding pitcher in the major leagues, but in my mind, the award should go to Mudcat Grant, who is a much better fielder then I am.”12

It should have been an omen to Grant when he started the 1967 season on the shelf. He was struck in the forearm during the last week of spring training, and missed the first two weeks of the season. Mele had fired Sain at the end of the 1966 season, and he himself was let go when the Twins got out of the gate playing at .500. Cal Ermer, who was the skipper at Triple-A Denver, took over the reins. Many of the current Twins had come through the minors under Ermer’s watch and supported the change. Due in part to injury, Grant made only 14 starts, and did much of his work out of the pen. He finished with a 5-6 record and a 4.72 ERA. The Twins narrowly lost the pennant in a final-weekend showdown with the Red Sox.

Because of Ermer’s erratic use of Grant and his injuries, Grant was looking for a fresh start and an exit from Minnesota. He got his wish when he and shortstop Zoilo Versalles were shipped to Los Angeles for catcher John Roseboro and pitchers Ron Perranoski and Bob Miller. Grant was elated to be joining the Dodgers. “During last season I felt so terrible, I couldn’t be happy,” remarked the right-hander. “It was a problem between the Minnesota manager and management and myself. Some of it was racial, too. They made me feel as though I wasn’t even a man. I’d pitched only 95 innings and it isn’t because of my knees, either. I have lived with the knee trouble for years. But I told them I couldn’t remain with them and wanted to be traded.”13 Dodgers manager Walter Alston used Grant out of the bullpen. Indeed, he made only four starts in 37 appearances, going 6-4 with a 2.08 ERA. “I tell you, he’s working his tail off for us,” said Alston.14

Before the 1969 season, Grant was selected by the Montreal Expos in the expansion draft. He made 10 starts with a record of 1-6 before being dealt to St. Louis for pitcher Gary Waslewski on June 3. Pitching in long relief, Grant went 7-5 for the Cardinals. At the end of the year, St. Louis sold Grant to Oakland. Pitching exclusively out of the bullpen, the 34-year-old Grant showed he had plenty left in the tank as he had 24 saves, a 6-2 record, and a sparkling 1.83 ERA. From May 17 to June 16, Grant pitched 28 innings and allowed one earned run, lowering his ERA to a minuscule 0.79. Oakland sold Grant to Pittsburgh in mid-September. He pitched in eight games, all in relief, for the Pirates.

The 1971 season was Grant’s last. He started the season in Pittsburgh but was sold back to Oakland on August 10. He saved 10 games for the two teams. Grant appeared in the League Championship Series against Baltimore and pitched two scoreless innings in Game Three. Released after the season, he was unable to make the Indians out of spring training in 1972 and pitched in 49 games with the Iowa Oaks of the American Association before retiring.

In retirement, Grant tried his hand at many jobs in and out of baseball. He worked in the Indians community relations office and was the analyst on Indians TV broadcasts. He later worked on broadcasts for the Athletics. At the request of Hank Aaron, the Atlanta Braves’ director of player personnel, Grant was a pitching coach for the Durham Bulls of the Class A Carolina League in the mid-1980s.

Grant later worked for an Anheuser-Busch distributor and for Nationwide Advertising in Cleveland, and was the spokesman for many sponsors. He wrote a book in 2005 called The 12 Black Aces, which detailed the lives of 12 black major-league pitchers who had won 20 games in a season.

Grant moved to Los Angeles, where he became a community activist and public speaker. As the number of black players has dwindled in the major leagues, Grant worked to counter the downward trend. Part of the problem, he said, is that former major leaguers need to take the responsibility to spread the word about baseball. “We just gotta motivate them to play and we’ve got to be around,” Grant said in 2008. “We haven’t been around enough. Now, part of that is the African-American ex-players’ fault, too, because we haven’t been there. Even though we see tons of children, we haven’t been in the inner city like we should.”15 Grant may have had something to do with that very issue right within his own family. His nephew, Domonic Brown, was drafted by the Phillies in the 20th round in 2006 and made his big-league debut in 2010 for the Phillies.

Postscript

Grant died at the age of 85 on June 11, 2021, in Los Angeles.

Sources

Pluto, Terry, The Curse of Rocky Colavito (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994).

Thielman, Jim, The Cool of the Evening (Minneapolis: Kirk House Publishing, 2005).

The Sporting News

Sports Illustrated

Baseball Digest

National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives

minors.sabrwebs.com/cgi-bin/index.php

retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Article, publication unknown, in Grant’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

2 Ibid.

3 Terry Pluto, The Curse of Rocky Colavito, 66-67.

4 Pluto, 68.

5 Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 18, 1960

6 Ibid.

7 Baseball Digest, August 1961, 5-7.

8 Ibid.

9 Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 16, 1964.

10 Jim Thielman, The Cool of the Evening, 55.

11 The Sporting News, July 30, 1965, 9.

12 The Sporting News, October 23, 1966, 14.

13 Los Angeles Times, March 9, 1968.

14 Sports Illustrated, April 28, 1968.

15 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 15, 2008.

Full Name

James Timothy Grant

Born

August 13, 1935 at Lacoochee, FL (USA)

Died

June 11, 2021 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.