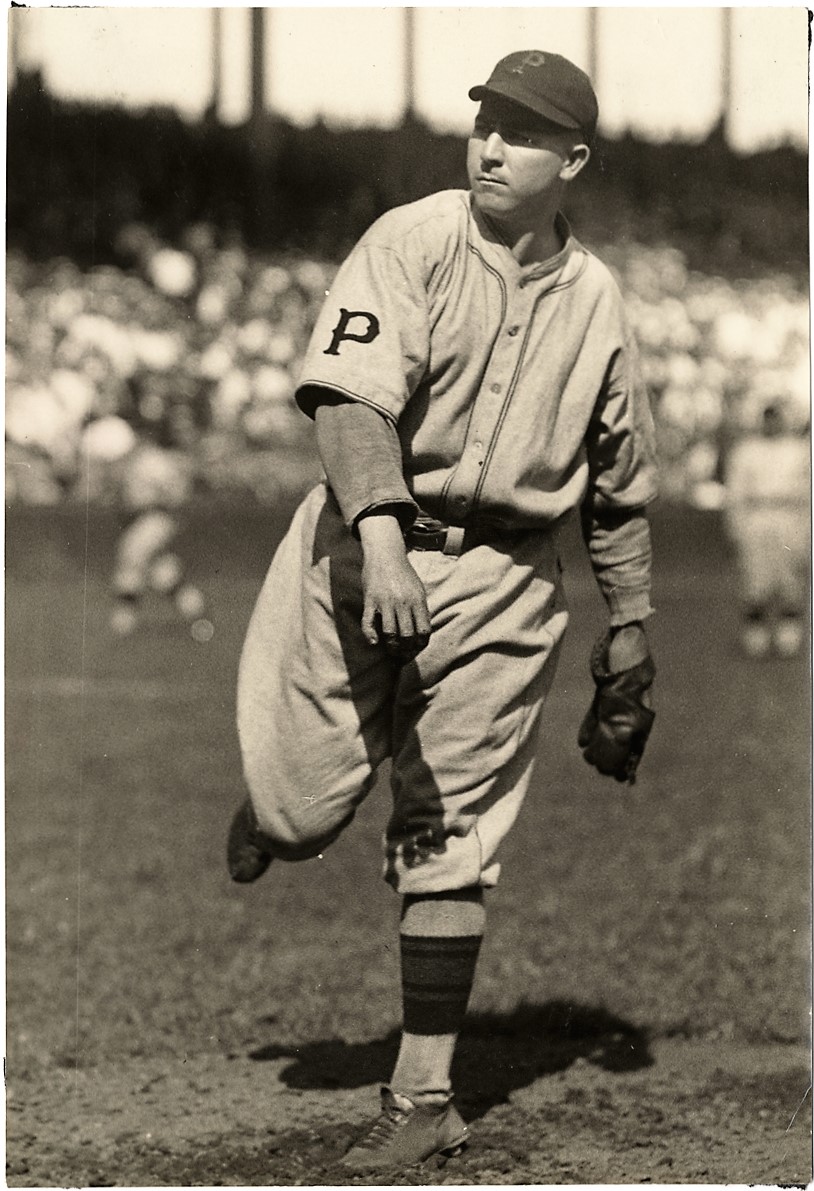

Vic Aldridge

Vic Aldridge, the Hoosier Schoolmaster, taught big-league hitters about his sharp-breaking curveball and nasty heater for nine seasons, notably in the Windy and Smoky Cities. In 1925 he held class in the World Series, disciplining his pupils from the nation’s capital with two complete games in the Pirates’ championship campaign.

Vic Aldridge, the Hoosier Schoolmaster, taught big-league hitters about his sharp-breaking curveball and nasty heater for nine seasons, notably in the Windy and Smoky Cities. In 1925 he held class in the World Series, disciplining his pupils from the nation’s capital with two complete games in the Pirates’ championship campaign.

Victor E. Aldridge was born on October 25, 1893, on the family farm in the small Baker Township hamlet of Crane in rural Martin County, Indiana, about 90 miles southwest of Indianapolis.1 His parents were native Indianans Christopher Columbus (known as Chester) and Martha (Eddington) Aldridge. Both widowed, they were in their mid-40s when they married around 1892 and started their second family. Vic was their only child, though they had children from previous marriages. Vic attended the Tempy School, a one-room schoolhouse, located near Cale and Indian Springs. According to baseball historian Lee Allen, Vic walked seven miles round-trip to attend Trinity Springs High School, which he completed in three years, graduating in 1911.2

In the fall of 1912, Aldridge matriculated at Central Normal College in Danville, Indiana. The following year, the 19-year-old Aldridge also began a four-year stint teaching part-time at local county schools. His unique sobriquet during his big-league playing career, the Hoosier Schoolmaster, was derived from the title of a popular novel from 1871 by Edward Eggleston.

The erudite Aldridge was not just a bookworm. He began playing ball in farm pastures as a child. “[He] is better known around the middle west for his pitching proclivities than for his ability to pound intelligence into the knobs of Indiana youngsters,” read one poetic report.3 Slight in build, standing just 5-feet-9 and weighing about 150 pounds, Aldridge was a right-handed curveballing sensation. He hurled for his college team in 1913 and 1914 and also for the Grays, a semipro team in Peru, a bustling town of about 10,000 residents 85 miles north of Indianapolis. By the end of 1914 he had attracted the attention of Jack Hendricks, manager of the Indianapolis Indians of the Double-A American Association. He was invited for a tryout and was signed to a contract paying $150 per month, which was less than what he made playing semipro ball.4

Aldridge’s professional career began with the Indians at their spring-training camp in San Diego, in 1915. The 21-year-old green recruit was optioned to the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League. After one bad outing he was sent packing to the Erie (Pennsylvania) Sailors in the Class B Central League. There he “developed into a bear,” posting a 19-9 slate with a 1.62 ERA, a mark bettered only by Art Nehf’s 1.38.5

In 1916 Aldridge was back with the Indians in spring training, which had been relocated to Albany, Georgia. One step below the majors and facing players practically all of whom had or would have big-league experience, the 22-year-old Aldridge emerged as a bona fide prospect and caught the eye of the Chicago Cubs. On August 27 Cubs owner Charles Weeghman purchased Aldridge (16-14, 2.40) on the recommendation of scout Tom O’Hare, along with pitcher Rex Dawson (20-14), just weeks before the players would have become eligible for the major-minor-league draft on September 15.6 O’Hare gushed about Aldridge’s “sweetest looking curve ball” and “his world of nerve,” and predicted big-league success.7 In his first start after his sale, Aldridge celebrated by tossing a no-hitter against the Columbus Senators.8 He extended his streak of hitless innings to 19 with another victory, 2-1, against the Senators two days later.9

Aldridge was a long shot to stick with the Cubs in 1917, but he impressed first-year skipper Fred Mitchell with his curves during spring training in Tampa. The staff’s youngest hurler, the 23-year-old Aldridge was overwhelmed in a forgettable debut, a start against the St. Louis Cardinals at Weeghman Park (which was later renamed Wrigley Field in 1927) on April 15. He yielded four runs in three innings and was tagged with the 5-3 loss. It was a different story in his next appearance, when he tossed six scoreless innings of relief to pick up his maiden victory, on April 24 against the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field.

On May 16 Aldridge pitched with “warlike method,” noted sportswriter James Crusinberry of the Chicago Tribune, making reference to America’s declaration of war on Germany the previous month.10 The five-hit shutout against the Boston Braves was Aldridge’s third win in eight days, all on the road, and the surging Cubs’ ninth straight. They had a three-game lead atop the NL standings but commenced a season-long decline thereafter, finishing in fifth place again (74-80). Aldridge (6-6) made 30 appearances, including six starts, and logged 106⅔ innings.

Aldridge married Cleta B. Wadsworth, from Indian Springs in Martin County, on February 22, 1918, in Louisville, Kentucky. Aldridge’s college education gave him employment opportunities that most ballplayers could only dream about; consequently, he didn’t shy away from rejecting what he considered lowball contracts. In 1918 he refused the Cubs’ salary offer and didn’t report to spring training. He finally signed in mid-May, but made only three relief appearances in July before he enlisted in the Navy.11

The newlywed reported to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Virginia in late July. He trained on a minesweeper and eventually rose to the rank of chief petty officer. Organized sports were a vital morale-boosting component of the Navy training center, where dozens of professional baseball players served. Aldridge played on the Minesweepers, one of eight teams in the Fifth Naval District Ball League; his teammates included fellow Cub Pete Kilduff; the Brooklyn Robins’ Ernie Krueger; Al Baird of the New York Giants; and Bill Morrisette of the Philadelphia Athletics.12

With the war over, Aldridge was back with the Cubs. The reigning pennant-winners conducted spring training in Pasadena, California, in 1919. But things didn’t go as he had planned. He was optioned to the Los Angeles Angels of the Double-A Pacific Coast League and threatened to quit. The 25-year-old eventually had a change of heart and reported to player-manager Red Killefer’s club. Over the next three seasons, Aldridge proved to be a durable workhorse, winning 15, 18, and then 20 for the league champs in 1921. That season Aldridge posted the circuit’s lowest ERA (2.16) and allowed the fewest hits per nine innings (7.3). Sought by a number of big-league teams, Aldridge was reacquired by the Cubs along with Jigger Statz in exchange for six players and cash.13

Coming off a seventh-place finish, skipper Bill Killefer (Red’s brother), who had replaced Johnny Evers in midseason, desperately needed to infuse a weak staff with pitching. Cubs beat reporter Irving Vaughan opined that Aldridge would be “counted on a great deal” after the 28-year-old made a favorable impression on teammates at the club’s new spring-training site. That was Catalina Island, team owner William Wrigley’s paradise located some 20 miles off the coast of Los Angeles.

Aldridge’s second stint with the Cubs unfolded differently than his first. In his season debut, he hurled an “airtight ball game,” noted sportswriter Frank Smith in the Tribune, holding the Reds to six hits in a 6-1 victory at Crosley Field.14 Two starts later, he belted a two-run walk-off triple in a complete game against the Pittsburgh Pirates in his season debut at Wrigley Field. Described by Smoky City sportswriter Charles J. Doyle as the “pitching marvel of the season,” Aldridge won his fifth straight start in a wild 11-7 affair on May 6 at Forbes Field, in which he also blasted five singles in as many trips to the plate.15

He came down with a sore arm and lost eight of his next 11 decisions while the Cubs fell under .500 by the end of June. In the second game of an Independence Day twin bill in Pittsburgh, Aldridge performed the “most scintillating achievement of the day,” noted Doyle. The “pedagogue of the mound” tossed a brilliant two-hit shutout.16 That commenced a streak of five consecutive complete-game victories, including a 12-inning outing against the league-leading New York Giants.

While the Cubs got as close as 3½ games to the Giants’ lead in August, they faded down the stretch, in part because of Aldridge’s sudden ineffectiveness. He went 1-6 over the last six weeks of the season and seemed fatigued. One reason for his struggles might have been his appetite. “Vic liked his victuals and was indiscreet about eating,” write the Chicago Daily News. The paper noted that he was “given to corpulency and piles on weight so thickly around his shoulders that he is not free and loose when pitching.”17 Aldridge struggled with his weight (typically in the 175-180 range) the rest of his career.

The Cubs posted a winning record for the first time since 1919, but finished in fifth place while the Hoosier Schoolmaster emerged as the club’s best hurler, tying Pete Alexander for the team lead with 16 wins and 20 complete games, and paced the staff in innings (258⅓), starts (34), and ERA (3.52).

Emboldened by his success, Aldridge rejected the Cubs’ contract offer in 1923 and was left in Chicago as pitchers and catchers departed for Catalina Island. He eventually reported about 10 days later. Aldridge tossed a complete game to beat the Pirates in his season debut, 10-5, and then whitewashed the Cardinals on two hits in his next start. While the Cubs struggled to play .500 ball, Aldridge emerged victorious over the New York Giants and Mother Nature on June 6 at Cubs Park, located a mile west of Lake Michigan. According to the New York Times, “fog lowered and raised itself off the field, at times making it difficult for the fans and players and impossible for the teams to see the ball.”18 Aldridge curved his way to a three-hitter, winning 6-1.

Four days later Aldridge once again proved impervious to the Windy City elements – natural and unnatural – in his next start, overcoming what Frank Schreiber of the Tribune called “rain and mud and the weird, shrill whistling of a kiltie bagpipe band” to blank the Boston Braves on six hits.19 Aldridge won five straight starts and a career-best eight consecutive decisions. However, that stretch was interrupted by a sore arm that caused him to miss about three weeks in July, and he was sidelined again for three weeks in August. Propelled by 36-year-old Pete Alexander (22-12, 3.19), Aldridge (16-9, 3.48), and 22-year-old Tony Kaufman (14-10, 3.10), the Cubs (83-71) were back in the first division, albeit in fourth place.

Killefer was none too happy when Aldridge arrived overweight for spring training in 1924. Described by the Tribune’s Irving Vaughan as the “man who despises work,” Aldridge was forced to wear a rubber shirt and sent hiking in the mountains of Catalina Island to get into shape.20 Named Opening Day starter, Aldridge was whacked around and dropped four of his first five decisions. He turned things around beginning on May 17, when he won the first of seven straight starts while the Cubs briefly flirted with first place, holding a half-game lead on a few occasions.

But the North Siders, still a few years away from their ascent to pennant-contending status, came back to earth. On September 18 Aldridge won his last game of the season, providing the game-winning single to drive in Gabby Hartnett in the 11th inning to beat the Braves in Boston, 4-3. He concluded the season with two more extra-inning affairs, but was victimized by walk-off hits both times. The workhorse of the staff, Aldridge (15-12) paced the club in starts (32) and innings (244⅓), tied his career high with 20 complete games, and posted a robust 3.50 ERA for the fifth-place Cubs (81-72).

On October 27 the Cubs and Pirates executed one of the blockbuster trades of the decade. The Bucs had contended for the NL pennant, finishing runner-up in 1921 and then in third place the next three seasons. Skipper Bill McKechnie sought to rid his club of what he perceived as negative influences. Consequently, he dealt away disgruntled veteran Wilbur Cooper, widely considered the NL’s premier southpaw, coming off his fourth season with 20 or more wins in the last five years, and two hard-drinking rabble-rousers, first baseman and five-year starter Charlie Grimm and future Hall of Famer veteran Rabbit Maranville.

In return the Cubs sent Aldridge, 24-year-old first baseman George Grantham, coming off his first of eight seasons with a batting average of at least .300, and prospect Al Niehaus. Pittsburgh newspapers lambasted the trade, which on paper seemed lopsided and a veritable fleecing. Unbeknownst to anyone, however, was that one of the most exciting seasons in Pirates history was less than five months away.

Aldridge was set to join the majors’ most rugged staff, one that had featured primarily five pitchers the previous season: Ray Kremer (18-10), Johnny Morrison (11-16), Lee Meadows (13-12), Emil Yde (16-3), and the since departed (Cooper (20-14). They had combined for 142 starts and 1,189 innings. Already considered a downgrade from Cooper, Aldridge engaged Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss in a bitter contact dispute and missed all of spring training and the ensuing exhibition season. “When he is in form,” opined the Pittsburgh Post about the missing hurler just a week before the season opener in Chicago, “he is one of the greatest twirlers in the game.”21

Aldridge finally showed up in Chicago on April 14 just hours before the Pirates were scheduled to play the Cubs. After rejecting the Pirates’ salary offer yet again, Aldridge worked out at Cubs Park with the team. He finally signed the deal after the game to conclude the majors’ longest holdout of the season.22 According to the Gazette Times, Aldridge’s contract called for a $10,000 salary, about eight times what the average industrial worker earned at the time.

As could be expected from missing spring training, the stocky twirler struggled getting into pitching form. In his first two starts, he yielded 13 earned runs in 9⅓ innings as the Pirates slumbered through early-season doldrums, in late May falling as many as nine games behind the Giants, seeking their fifth straight pennant. As the Pirates heated up in June, Aldridge was hit-or-miss. After failing to complete the fifth inning in three of his last four starts, he tossed a complete game to beat the Brooklyn Robins, 4-2, at Ebbets Field on July 13, giving the surging Pirates their 33rd win in 46 games to maintain a one-game lead on John McGraw’s squad. With the teams trading the top spot in July, the Bucs took the lead for good on August 3 when Aldridge stroked a walk-off single in the 11th to beat the Philadelphia Phillies, 3-2, completing a doubleheader sweep at Forbes Field.

The Pirates dismantled opposition the rest of the season, winning almost two-thirds of their games (39-20). They captured their first pennant since they won the World Series in 1909. Aldridge finally hit his stride over the last six weeks of the season. From August 18 to September 19, he won eight straight decisions to resurrect an inconsistent campaign. Against the lowly Phillies in the bandbox Baker Bowl on September 1, the schoolmaster tied his career best with nine punchouts and also blasted the first of his career two round-trippers. (Aldridge was a .229 lifetime hitter.)

The Pirates (95-58) were a complete team. An offensive powerhouse, the squad led the majors in scoring (6.0 runs per game) and batted an NL-best .307. However, their pitchers set them apart from other teams. The staff lacked an overpowering superstar, like the Robins’ Dazzy Vance, but featured a durable quintet, each of whom logged at least 200 innings: Aldridge (15-7), Kremer (17-8), Meadows (19-10), Morrison (17-14), and Yde (17-9). The 43-year-old Babe Adams, who had won 12 games for the Pirates’ last championship team, chipped in with 101⅓ innings. It was essentially a six-man staff.

Nominal favorites against the Washington Senators (90-61), the Pirates lost the opener to Walter Johnson, 4-1. Aldridge took the mound in Game Two, facing spitballer Stan Coveleski, coming off his fifth season with 20 or more victories. Lauded for his “cool hand, a steady arm and calm nerves,” Aldridge emerged victorious, 3-2.23 In an instant classic, Aldridge overcame a bases-loaded jam in the fifth without permitting a run. After Kiki Cuyler whacked the game-winning two-run home run to give the Pirates a 3-1 lead in the eighth, Aldridge loaded the bases with no outs in the ninth and escaped with just one run for the route-going win. “When the final story of this game is written,” noted New York Times columnist James R. Harrison, “they might call it ‘The Heart of a Pitcher.’”24

The Pirates lost the next two contests as the series moved to D.C. Aldridge and Coveleski, “the schoolmaster against the coal miner,” had a rematch in Game Five at Griffith Stadium with the series on the line.25 Cuyler’s seventh-inning single gave the Bucs a 3-2 lead and Coveleski didn’t finish the inning. Aldridge followed up his Game Two seven-hitter with an eight-hitter for his second complete-game victory. “Walter Johnson may be the best pitcher in this world’s series,” gushed Harrison, “but the palm of coolness should go to Aldridge.”26 Nationally syndicated columnist Damon Runyon called Aldridge the “bulldog of baseball” and praised his tenacity and courage under fire.27

Kremer’s six-hitter in Game Six made for a dramatic climax of what many considered one of the greatest World Series in history. McKechnie tabbed Aldridge on two days’ rest to start Game Seven against the Big Train on a rainy, cold day in Pittsburgh. It was a near-disastrous decision. Aldridge faced only six batters, yielding two singles, walking three, unleashing two wild pitches, and recording only one out. Two runs scored, and he was charged with two more that reliever Johnny Morrison permitted to score. It was one of the biggest meltdowns in World Series history, but Aldridge was saved by his resilient teammates. The Pirates mounted a furious comeback against Johnson, with Cuyler striking the decisive blow again, a two-out, two-run ground-rule double in the eighth to give the Pirates a 9-7 victory for the title.

Widely expected to capture another pennant in 1926, the Pirates had a season as disappointing as their previous season was exhilarating. The team fought with management and ultimately imploded, leading to the ouster of McKechnie at the end of the season. Everything looked rosy, however, at spring training in Paso Robles, California, where Aldridge reported on time. The Bucs’ Opening Day starter, Aldridge was bombed for six runs in as many innings in a loss to the Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park on April 13, but turned around to post three consecutive complete-game victories in 10 days in what proved to be the high point of his season. He soon came down with arm woes and struggled with his control.

Just as the Pirates were heating up in July and moved into first place near the end of the month, the team seemed to be on the edge of mutiny. Johnny Morrison, who had already been disciplined for his unannounced leaves from the team, went AWOL again and was suspended indefinitely. On July 21 Aldridge failed to retire a batter and was pulled in the first inning of the first game of a twin bill against the Robins. He showered, dressed, and left the ballpark, and was ultimately fined for insubordination.28 Coincidental or not, he didn’t pitch for two weeks thereafter. Sportswriter Lou Wollen of the Pittsburgh Press reported about the hurler’s “strained arm,” which surely could have been the case.

However, McKechnie could also have been trying to tamp down the insurrection around him. Around the same time, a trio of veteran players — Babe Adams, Carson Bigbee, and Max Carey — voiced their displeasure with club vice president and former skipper Fred Clarke’s presence on the dugout bench and what they considered meddling in the team’s affairs. This eventually became known as the ABC affair, and resulted in the release of all three players on August 13. Aldridge returned from his arm problem but was ineffective. On September 12 he won for the first time in two months, but it proved to be his last appearance of the season — he returned home to Indiana after the death of his father. The Pirates finished in third place (84-69), while Aldridge (10-13) completed 12 of 26 starts with a worse than league average ERA (4.07) in 190 innings.

The Pirates weren’t sure what to expect from Aldridge in 1927. Throughout spring training he nursed what was described in the Pittsburgh Press as a “kinked elbow.” It required medical attention from team physician Dr. Charles Spencer and sidelined him for the first 10 days of the season.29 Steel City sportswriter Lou Wollen, noting the “frequent run ins” the player had with McKechnie, wasn’t sure how he’d get along with new skipper Donie Bush, a disciplinarian. It led to a harsh judgment that the “temperamental Aldridge will be of questionable value to the Corsairs.”30

Much like the Pirates, Aldridge had a streaky season. He won his first game more than a month into the season, but then strung together five complete-game victories in 17 days from May 18 to June 3, propelling the Bucs from three down to four up in the pennant race. In the final of those wins, Aldridge was “broken out in a rash of heroics,” gushed beat reporter Charles J. Doyle, as the 33-year-old fanned three straight batters with the bases filled against the Phillies.31 [In an era of few strikeouts, teams averaged 2.79 punchouts per game; in 2018 that average had increased to 8.48.] Winless for a month, Aldridge copped five consecutive complete-game decisions in July, including a two-hitter against his former team, to record his last of eight career shutouts.

The Pirates played sluggishly in August, falling as many as six games behind the upstart Cubs, but roared back at the end of the month. Aldridge won his first four starts in September, the last of which was a duel with the Robins’ Jesse Petty in the first game of a twin bill at Forbes Field on September 17. Kremer completed the afternoon sweep to give the Pirates their 11th straight win and increase their lead over the New York Giants to 4½ games.

Three straight losses to the New Yorkers evoked memories of 1921 club’s late-season collapse, but Aldridge came through with his biggest victory of the season. Taking treatment from Dr. Spencer prior to the game, Aldridge tossed a four-hitter against the Cubs to win his fourth straight decision by one run, 2-1.32 Kremer, as he did eight days earlier, completed the twin-bill sweep, to increase the Pirates lead to two games over the Cardinals and 2½ over the Giants. The Bucs held on to win the pennant on the last weekend of the season.

Once again the NL’s highest-scoring team, the Pirates had a durable quartet of hurlers, each of whom logged more than 200 innings: Carmen Hill, who had won just nine games since 1915, seemingly came out of nowhere to pace the club with 22 victories; fellow spectacles-wearer Meadows (19-10), Kremer (19-8), and Aldridge (15-10) rounded out the staff.

The Pirates (94-60) were overwhelming underdogs facing what many historians have considered the best team in baseball history: the New York Yankees (110-44). The Bronx Bombers, featuring Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, led the majors in scoring and had the best team ERA. They swept the Pirates in four games, but the Series was not as one-sided as expected — Games One and Four were close one-run victories. Aldridge started Game Two and was routed, 6-2, giving up 10 hits (all singles and a double) and walking four, leading to six runs in 7⅓ innings.

About a week before pitchers and catchers were scheduled to report to spring training in 1928, the Pirates traded Aldridge to the Giants in exchange for spitballer Burleigh Grimes on February 11. Ol’ Stubblebeard went on to top the NL with 25 wins for the Pirates in 1928 and won 42 in two seasons. Aldridge, however, had a rocky relationship with the Giants. He refused to sign his contract, enraging skipper John McGraw. Aldridge’s battle with Little Napoleon made his contract squabble with McKechnie in 1925 look like child’s play. Still a holdout on Opening Day, Aldridge was suspended for 30 days on April 21.33 He finally signed on May 6, but was ineffective once in uniform.34 With a 4-7 slate and 4.83 ERA in 119⅓ innings, Aldridge was optioned to the Newark Bears of the International League on September 2.35 The Schoolmaster never made it back to the big leagues.

Aldridge played out September in Newark and was back with the Bears for a few months in 1929 before calling it quits. Two year later, he attempted a brief comeback, lasting five games with Newark. Yet his baseball days were far from over. Aldridge continued playing semipro ball in the Terre Haute area for the next decade.

In parts of nine seasons in the majors, Aldridge compiled a record of 97-80, completed 102 of 205 starts among his 248 appearances, and logged 1600⅔ innings with a 3.76 ERA. He also won 96 games in the minors, logging 1,426⅔ innings.

Aldridge and his wife, Cleta, lived the rest of their lives in Terre Haute, where Vic had purchased a bungalow on 2412 South 8th Street with his World Series earnings from 1925. The Schoolmaster went back to school in 1933, earning his law degree in 1935 at Voorhees Law School in Terre Haute. He was admitted to the bar in 1937. The Aldridges had one child, Victor Jr., born in 1919. Aldridge followed his successful baseball career with an equally successful, though less glamorous, one as an attorney and politician. He served as a Democrat in the Indiana State Senate for 12 years, from 1937 to 1948.

Aldridge died on April 17, 1973, at the age of 79 and was buried at Trinity Springs cemetery in Martin County.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Aldridge’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, SABR.org, extensive use of the archives of the Chicago Tribune, Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh Post, and Pittsburgh Gazette Times, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 In an interview with baseball historian Lee Allen, Aldridge said that he did not have a middle name, just the initial E. Given his mother’s maiden name (Eddington), one can surmise that that was his middle name. Other records show that he had neither a middle name nor a middle initial. Player’s Hall of Fame questionnaire.

2 Player’s Hall of Fame questionnaire.

3 “Hoosier Is Cubs Marvel,” El Paso (Texas) Herald, February 26, 1917: 10.

4 “Aldridge May Be With Peru Club,” Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, March 4, 1916: 21.

5 “Indians Pitcher Is Real Bear in Box and Bat in Central,” Indianapolis News, June 12, 1915: 8.

6 “Big Series With Omaha if Indians Win Flag,” Indianapolis News, August 28, 1926: 10.

7 Hoosier Is Cubs Marvel.”

8 “No-Hit Game Is Credited to Aldridge,” Indianapolis Star, September 3, 1916: 53.

9 John H. Gruber, “No Hits in 19 Consecutive Innings Was Pitching Feat of Aldridge While Wearing Uniform of the Hoosier, Pittsburgh Post, November 9, 1924: 30.

10 Jams Crusinberry, “Nine Straight for Cubs, With More to Come,” Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1917: 12.

11 “Schoolmaster Back in Game,” Indianapolis News, May 16, 1918: 18.

12 “Fine Naval Base Sports, Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times Leader, November 7, 1918: 16.

13 Gruber. The players were Charlie Deal, Tom Daly, John L. Sullivan, Babe Twombly, Elmer Ponder, and Lefty York.

14 Frank Smith, “Ump Cleans bench of Cubs; Mates Make Reds Suffer,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1922: 25.

15 Charles J. Doyle, “Chilly Sauce,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, May 7, 1922: 32.

16 Charles J. Doyle, “Bucs Drop Doubleheader to Cubs, 8-4, 8-0,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 5, 1922:

17 Chicago Daily News reprinted in “Eating May Cause Vic Aldridge to Lose One,” Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, November 10, 1922: 8.

18 “Giants Get 3 Hits, Beaten by Cubs,” New York Times, June 6, 1923: 16.

19 Fran Schreiber, “Mud, Rain, and Bagpipe Band, But Cubs Win,” Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1923: 25.

20 Irving Vaughan, “Killefer’s Cubs Find Avalon Far From Paradise,” Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1924: 23.

21 Pittsburgh Post, April 7, 1925: 13.

22 “Holdout Star Accepts Terms After Work Out Before Opener,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, April 15, 1925: 11.

23 Hugh Jennings, “Hugh Jennings Is Stirred by Thrills of Game,” New York Times, October 9, 1925. 19.

24 James R. Harrison, “Pirate Victory Ends Myth of Faint Hearts,” New York Times, October 9, 1925: 18.

25 Stanley R. “Bucky” Harris, “Vic Aldridge Proves Mettle Under Fire; Wright Is Lauded,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, October 9, 1925: 12.

26 James R. Harrison, “Pirates Hit Stride; Give Best of Series,” New York Times, October 13, 1925: 26.

27 Damon Runyon (Universal Service), “Aldridge, Bulldog of Baseball’s Ne’er Quits,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, October 13, 1925: 11.

28 “Vic Aldridge Fined,” Pittsburgh Press, July 21, 1926: 30.

29 Lou Wollen, “Aldridge’s Arm Ailing,” Pittsburgh Press, April 7, 1927: 34.

30 Lou Wollen, “Several Vets Are Slipping,” Pittsburgh Press, January 30, 1927: 23.

31 Charles J. Doyle, “Vic Aldridge Strikes Out Three With Bases Full,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, June 4, 1927: 11.

32 Lou Wollen, “Flag Chances Are Enhanced,” Pittsburgh Press, September 26, 1927: 22.

33 “Aldridge, Holdout, Suspended for Thirty Days, by McGraw,” New York Times, April 22, 1928: 152.

34 AP, “Vic Aldridge to Play for Giant Outfit,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), May 7, 1928: 7.

35 AP, Aldridge Goes to Newark on Option for Rest of Year,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), September 3, 1928: 17.

Full Name

Victor Aldridge

Born

October 25, 1893 at Crane, IN (USA)

Died

April 17, 1973 at Terre Haute, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.