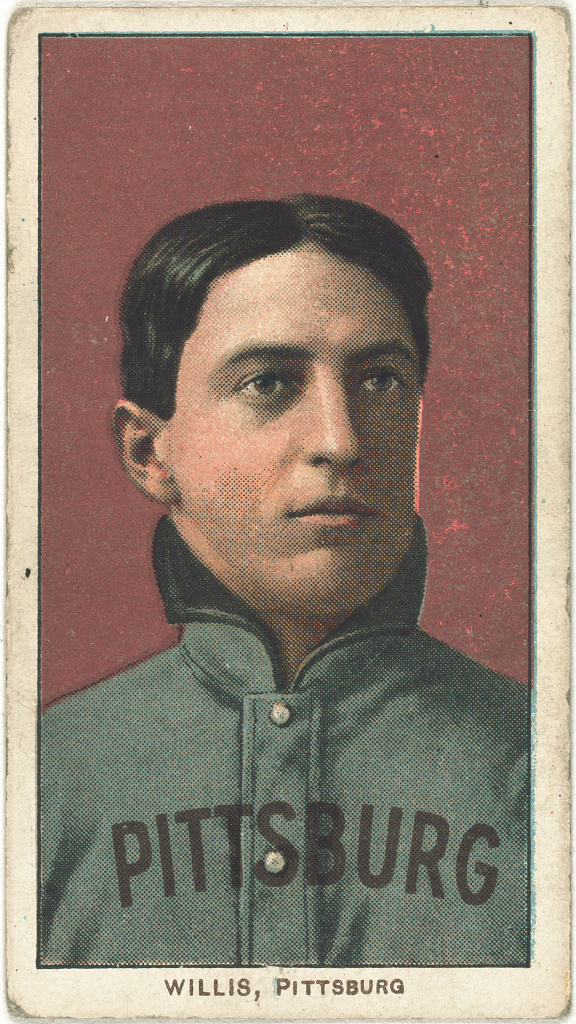

Vic Willis

As a rookie in 1898, Vic Willis won 25 games as a key member of the pennant-winning Boston Beaneaters, one of the top teams of the nineteenth century. Eleven years later in his penultimate season, Willis again won over 20 games as a member of the world champion Pittsburgh Pirates, one of the top teams of the Deadball Era. In between he pitched well enough to finish with 249 wins in only a 13-year career. A big man for his time at 6-foot-2, 205 pounds, Willis pitched with an overhand delivery and was known as a great strikeout pitcher. In 1995, nearly a century after his major-league debut, the Veterans Committee voted the hurler nicknamed the “Delaware Peach” into the Hall of Fame.

Victor Gazaway Willis was born on April 12, 1876 in Cecil County, Maryland. Soon afterward his family moved just across the state line to Newark, Delaware, where his father James supported the family as a carpenter, and his mother Mary ran the household. In Newark, Willis grew up playing baseball, starring on his school team at Newark Academy and later for Delaware College. By the time he was 18, Willis was playing semiprofessionally around the state of Delaware.

In 1895 as a 19-year-old Willis first entered organized baseball by joining the Harrisburg club in the nearby Pennsylvania State League. His workload piled up rapidly as he pitched in 16 of the team’s 37 games. The Harrisburg club folded in June, but Willis had gained some recognition and quickly caught on elsewhere—less than two weeks later he signed with Lynchburg in the Virginia League.

Overall, Willis pitched capably in 1895 despite the forced midseason relocation, and the next year he moved up to Syracuse of the Eastern League for the 1896 season. Willis battled illness nearly the entire year, but fought through it for a while to achieve a record of 10-6 by late July. Eventually the illness got the better of him, and on July 31 he left the team for the rest of the season to recuperate.

He returned to Syracuse healthy in 1897 and finished the season 21-16 as Syracuse won the league championship. Syracuse realized they had a budding star and hoped to sell him for $2,000, a fairly high price for the time. They ultimately settled for $1,000 and catcher Fred Lake from Boston. The major-league club developed its interest in Willis from the recommendations of Providence manager Billy Murray and Syracuse catcher Jack Ryan, previously a catcher in Boston.

In 1898 Willis joined the National League’s Boston Beaneaters, fresh off their fourth pennant in seven years. Willis was expected to help the team immediately, with one sportswriter commenting: “The ‘Wolf’ as he is termed ought to be a great winner for Boston,” and he further described the big right-hander as having good control, a change of pace, and a sweeping curve.1 The Boston Sunday Journal reported that “Willis has speed and the most elusive curves. His ‘drop’ is so wonderful that, if anyone hits it, it is generally considered a fluke.”2

Willis saw his first action April 20 in a mopup role in Baltimore when he entered the game in the sixth with the Beaneaters behind, 10-3. Willis showed some first-game jitters and over the final three innings he gave up eight runs while walking three and hitting two Oriole batters. Nine days later, in his first start, Willis pitched better and won 11-4 in a complete game. Willis surpassed even his high spring expectations by following up this first victory to finish 25-13 for the pennant winning Beaneaters.

The 23-year-old Willis followed up his superb rookie campaign with one of the best seasons of his career. He won 27, lost only 8 and finished second in ERA while pitching 342 innings. That year he led the league in allowing the fewest hits per game; a feat helped by hurling his only no-hitter on August 7. In the sixth inning of that game Washington pitcher Bill Dinneen hit a ball that took a bad hop and just eluded Boston third baseman Jimmy Collins. Fortunately for Willis this ball was scored an error and his no-hitter was preserved. After the season in February 1900 Willis married Mary J. Minnis, a union that would lead to two children, a girl and a boy born 15 years apart.

Years later Boston first baseman Fred Tenney recollected the team’s pitchers and fielders working in harmony, even if the outcome was not always as anticipated:

“I remember once Vic Willis was pitching for Boston and Jesse Tannehill was at the bat. Long [shortstop Herman] saw as Willis wound up that he was going to give Tannehill a low ball and Tannehill could wallop that kind. He was apt to paste them hard to right field.

“‘No, no; don’t give him that,’ cried Long, but Willis was just letting the ball go and Long darted across the diamond in front of the second baseman as fast as his legs could carry him. He knew that Tannehill was apt to slam the ball to right field, and he wanted to head it off. There were two strikes on Tannehill, and as luck would have it he missed this one and struck out. Long described a circle, came up to Willis from the direction of first base, grabbed him by the hand and exclaimed, ‘that’s the way to pitch, old boy!’”3

Despite a subpar 1900 season, Willis was still regarded as a top hurler, and in 1901 Boston paid him a $2,400 salary. At the end of the nineteenth century the National League’s magnates adopted a salary maximum of $2,400. For the top players, however, teams often supplemented this salary with additional payments, both above and below the table. Willis’ teammate, star pitcher Kid Nichols earning $2,400, held out prior to the 1899 season after winning the 1898 pennant because the team offered only $235 per man as a championship bonus.

In 1901 the American League challenged the National as a major league, and the completion between the leagues for ballplayers bid up salaries. As some of his teammates were leaving for greener pastures in the AL, Willis reportedly agreed to jump to the American League’s Philadelphia Athletics but soon changed his mind. Other star National League hurlers saw their salaries jump from the American League threat: Noodles Hahn leapt to $4,200, Christy Mathewson reportedly made $5,000, and Joe McGinnity $3,000. That year Willis turned in another good season with a 20-17 record and finished fourth in ERA while pitching over 300 innings.

In 1902 Willis responded sensationally to an incredible workload: he completed a league-high 45 games, the modern (since 1901) NL record; hurled 410 innings, the second-highest total in modern NL history; and led the league in strikeouts with 225. On May, 29 against New York Willis struck out a league-high 13 Giants; that only 450 spectators saw this game highlights how far this franchise had fallen in the new century from its recent championship days. Additionally, Willis was used in several key relief situations, and he has been retroactively credited with a league-high three saves.

The American League came calling again during the 1902 season. Detroit Tigers president Sam Angus met Willis in the Victoria Hotel and offered a large cash downpayment on a two-year contract of $4,500 per season. Naturally tempted by the cash and salary, Willis initially accepted, but again later reneged after Boston reportedly matched the offer. His services remained in dispute until after the season when he was awarded to Boston as part of the peace settlement between the two leagues.

Over the next three years Willis won only 42 games while toiling for the rapidly deteriorating Beaneaters. In 1904 when Willis finished with a league-high 25 losses, his 18 wins represented 33% of his team’s 55 victories. He also proved an excellent fielder that year and recorded 39 putouts, a modern NL record that would stand for nearly a century. Willis, who years later would complain about the team’s fielding ability, probably figured the only way to get some outs was to make them himself. His grandson remembered Willis saying: “those outfielders couldn’t catch a flyball with a peach basket.”4

Prior to the start of the 1905 season the now anemic Boston club offered a salary of only $2,400. Willis expressed displeasure with his drastic salary cut by threatening to jump to an outlaw league in Pennsylvania. He eventually rejoined the Beaneaters but may have wished he hadn’t. In 1905, with the league’s worst offense supporting him, Willis again led the league with 29 losses, the most ever in modern baseball. Not surprisingly, after this frustrating season Willis again flirted with the outlaw league.

This time, however, the Pirates rescued the Willis from the hapless Beaneaters. Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss surrendered three players in the trade for Willis: new third baseman Dave Brain, first baseman Del Howard and pitcher Vivian Lindaman. After the trade Willis sent a letter to Dreyfuss acknowledging his unhappiness on the Beaneaters and expressing his approval of the trade, and added: “Don’t believe those tales you hear about my being all-in. Wait until you see me in action for your team and then form your opinion of my worth to your team. I assure you that I am delighted to be a Pirate and that I will do my best to bring another pennant to the Smoky City.”5 Dreyfuss reportedly restored Willis’ $4,500 salary as well.

Willis started strongly for his new club pitching three straight shutouts early in the 1906 season. Now with a winning franchise again, Willis would win 21 to 23 games a year over his four years with the Pirates without ever losing more than 13 while consistently pitching around 300 innings a year. During his stint with the Pirates, Willis hurled the two one-hitters of his career.

The famous 1908 National League pennant race came down to the last game of the season for the Pirates. On Sunday October 4, the Pirates faced the Cubs in Chicago’s old West Side Park in front of 30,247 fans, the most to have ever seen a baseball game up to that point and 6,000 more than had ever previously crowded into that park. A win for the Pirates and they would win the pennant; a loss and they would, for all intents and purposes, be eliminated.

Pirates manager Fred Clarke selected the well-rested Willis to start against the Cubs’ Three-Finger Brown, another future Hall of Famer. Brown was on his way to an excellent 29-9 record but this would be his third game in six days. The Cubs jumped out to a 2-0 lead as the Pirates managed only three hits through the first five innings. The Pirates scored two in the sixth to tie the game. In the bottom of the sixth with two out Joe Tinker doubled and Willis and Clarke chose to intentionally walk catcher Johnny Kling to face Brown. Unfortunately for Willis and the Pirates, Brown singled in Tinker with the go ahead and winning run. The Cubs later added two insurance runs including another RBI from Brown and won the contest, 5-2.

In January of the following year, amid rumors of a salary dispute, Willis announced that he had decided to retire from baseball and claimed he could make more money back in his hometown of Newark, Delaware. By the time the season rolled around, however, Dreyfuss had brought Willis back into the fold

In mid-1909 Willis again pitched in one of the highest attended games to date—the grand opening of Forbes Field, one of the first concrete and steel stadiums. On June 30, amid great fanfare and the closing of many businesses at noon, 30,000 plus spectators including numerous baseball and Pennsylvania dignitaries packed the new stadium. The Reach Guide gushed on the unveiling: “Never, perhaps, in the history of the Old World or New—not excluding the assemblages in the Roman and Grecian amphitheaters and stadiums—was a scene more spectacular presented….”6 Willis started for the Pirates, once again against the Cubs, and pitched a four hitter. But the team lost 3-2 in a game Dreyfuss obviously wanted very much to win: “What a shame we had to lose that one. I’d have given my share of the gate to have won on this day.”7

Unlike the previous season, in 1909 the Pirates gave their opponents no opportunity for late season heroics by winning 110 games and outdistancing the second-place Cubs by 6½ games. Willis played a key role by winning 22 and losing only 11, winning 11 consecutive games over one stretch during the season. In the World Series against the Tigers, Willis pitched in just two games, the only World Series appearances of his career. He relieved Howie Camnitz in the third inning of Game Two, and Ty Cobb promptly stole home. Willis gave up three runs over his 6⅓ innings in relief as the Tigers won the game, 7-2.

With the Pirates up three games to two, Clarke gave Willis the Game Six start and a chance to win the Series. Despite being staked to a three run lead in the first inning, Willis could not hold the lead. Clarke pulled him after five innings with Detroit ahead, 4-3. Although the Pirates ended up losing Game Six, they came back to win Game Seven and the World Series two days later.

Despite his fine 1909 season, the Pirates waived Willis before the 1910 season amid allegations of disciplinary problems with manager Clarke during the previous summer and World Series. The chronically second-division St. Louis Cardinals claimed Willis, and The Sporting News reported that he “should have a year or two of high-class work left in him if he will behave himself.”8 Willis won only nine games for the seventh-place Cardinals, and just prior to the end of the season the team asked waivers on Willis.

During the offseason St. Louis sold Willis to the minor-league Baltimore Orioles of the Eastern League. Although some doubt existed whether Willis would report to the minors, he told the Baltimore Sun: “I feel very much satisfied to play in Baltimore.”9 Despite this apparent sale, both the Cubs and Reds put in a waiver claim for Willis. These waiver claims were ruled to be valid; St. Louis President Stanley Robison had mistakenly believed his waivers were good until the opening of the next season and consequently had to return Baltimore’s check. Willis ended up being awarded to Chicago for the $1,500 waiver price, but elected to retire rather than report to the Cubs.

With his playing career now over, Willis retired to his hometown of Newark where he purchased and operated the Washington House Hotel. Willis remained active in baseball, managing semipro and coaching at the youth and college level. He also spent time enjoying golf and raising bird dogs. Vic Willis was 71 when he died in Elkton, Maryland, on August 3, 1947, the victim of a stroke.

An updated version of this biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin. It originally was published in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

Many sources were consulted in preparing this biography. The most useful were The Sporting News (many issues), Harold Kaese’s The Boston Braves (Putnam, 1948), Fred Lieb’s The Pittsburgh Pirates (Putnam, 1948), Lois P. Nicholson’s Maryland to Cooperstown (Tidewater, 1998), Stephen Cunerd’s article, “Vic Willis: Turn of the Century Great,” from SABR’s 1989 Baseball Research Journal, several annual Reach Guides, Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria’s Honus Wagner (Henry Holt, 1996), and Vic Willis’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, February 12, 1898.

2 “Has Elusive Curves,” Boston Sunday Journal, July 2, 1899.

3 “It’s Done by Instinct,” Fort Wayne Daily News, January 28, 1911.

4 Vin Mannix, “Persistence Pays Off for Grandson,” Florida News, March 20, 1995.

5 The Sporting News, January 16, 1906.

6 “The National League’s Showplace,” The Reach Official American League Baseball Guide for 1910, (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Company, 2010), 126.

7 Frederick G. Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 133.

8 The Sporting News, February 24, 1910.

9 “Sporting News in Tablet,” Fort Wayne Daily News, January 12, 1911.

Full Name

Victor Gazaway Willis

Born

April 12, 1876 at Cecil County, MD (USA)

Died

August 3, 1947 at Elkton, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.