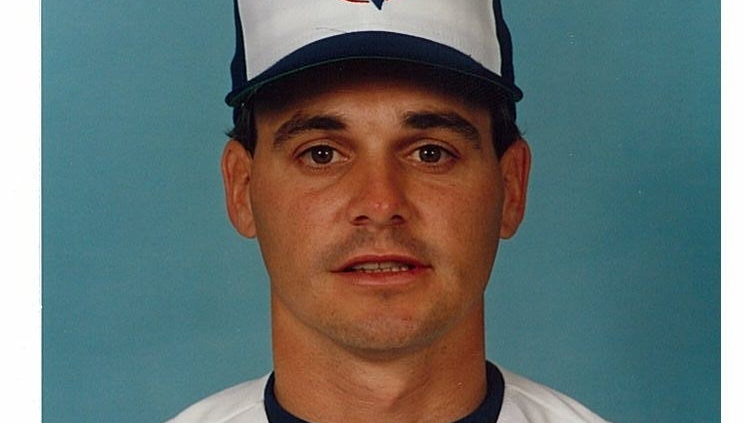

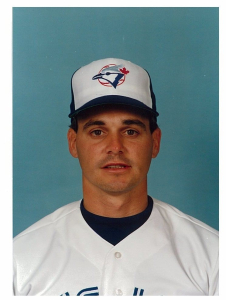

Jimmy Key

When you ask people to name Blue Jays starting pitchers of the 1980s and ’90s, they might answer with Jack Morris, Dave Stieb, Roger Clemens, and David Cone. Big arms accompanied by prominent personalities, pitchers who threw hard and had secondary wipeout pitches. Pitchers who were expressive on the mound, often showed emotion and, in some cases, had a fiery personality. Those attributes described what we defined as “aces.” However, one pitcher who won The Sporting News Pitcher of the Year twice (second only to Roger Clemens during that era) and won the final clinching game for two World Series champions, is frequently forgotten. Why? Maybe it was because his fastball wasn’t very speedy, his backdoor slider was fine but not flashy, and he had a quiet presence, an unassuming personality instead of the big-name starters of that era. Whatever the reason, his name may be forgotten, but his performance over those two decades cannot be.

James Edward Key was born on April 22, 1961, in Huntsville, Alabama, to Carol and Ray Key. Carol was a secretary who worked 30 years for NASA, while Ray was an engineer for the US Army for 35 years. Jimmy had two brothers, Richard and Mark, and a sister, Linda.

Ray was both father and coach and helped Jimmy develop his skills in baseball. When Jimmy practiced baseball, his father did not permit him to play catch like other kids his age. He wouldn’t be encouraged to throw it as hard as he could. If he tossed or pitched a ball, it had to be precisely located in the catcher’s glove. Ray preached that no pitch should be wasted; you should precisely locate the pitch every time.1

The control Key learned from his father never waned and led to success in his senior season at S.R. Butler High School. He went 10-0 with nine shutouts and a 0.30 ERA. Jimmy was also good on the other side of the field, hitting .410 with 11 home runs and 35 RBIs. His performance captured the attention of the Chicago White Sox, who drafted him in the 10th round of the 1979 amateur draft.2

The White Sox scouts weren’t the only ones to notice Key. Bill Wilhelm, head coach of the Clemson University Tigers, watched Key pitch in the state quarterfinal game, where he struck out 19 batters in 11 innings. “I was so impressed that I went up to him after the game and offered him a full scholarship,” said Wilhelm. “Without any hesitation and ever seeing Clemson, he (Key) said, ‘I’ll take it.’ He was certainly one of the easiest to recruit.”3

Heading to Clemson University and turning down the White Sox was an excellent decision for Key. He pitched in the 1980 College World Series. In 1982 he became the first Clemson baseball player to be named first-team All Atlantic Coast Conference at two positions in the same season – pitcher and designated hitter. Key won a league-best nine games (seven complete games) in 116 innings while hitting .359 with a school-record 21 doubles. In 1982 he was again drafted, by the Toronto Blue Jays, in the third round, and Key this time signed.4

At Clemson, Key majored in recreation and park administration. He met a young woman on a swimming scholarship, Cindy, who became his first wife and they had a daughter, Jordan.

Key’s success continued once he reached pro ball. The 6-foot-1, 185-pound left-hander pitched (14 games) in 1982 for the rookie-level Medicine Hat Blue Jays and the Florence (South Carolina) Blue Jays in the low Class-A South Atlantic League. In 1983 he split the season between Double-A Knoxville and Triple-A Syracuse. Having pitched in only 44 minor-league games, he made the major-league team in spring training 1984 and made his debut with Toronto on April 6, 1984. The Blue Jays manager, Bobby Cox, frequently liked to have rookie pitchers start in the bullpen. Key pitched in 63 games and led the Blue Jays with 10 saves in 1984, tied with right-hander Roy Lee Jackson.

In 1984 Baseball America described Key as “having a good assortment of pitches; he has the knowledge of how to use them to set up hitters.”5 This potential was seen by the Blue Jays, who moved him to the starting rotation to start the 1985 season. Key was part of the dominant rotation that helped lead the team to its first playoff appearance, finishing the season with a 3.00 ERA, 1.119 WHIP, and 5.0 WAR, and made his first All-Star Game appearance.6

In 1985 Key started 32 of his 35 games and posted a record of 14-6. Over the next couple of years, he became known for his control, a good sinker and curve, ability to change speeds on pitches, durability, and an excellent pickoff move. He won 14 games again in 1986.

Al Widmar, his pitching coach in Toronto, described Key as a pitcher, not a thrower. In a Baseball Digest interview in 1988, Widmar said, “He also throws a cut fastball with good movement on it. And his control is outstanding.”7

In 1987 Key took his performance to the next level and delivered what management saw when he was selected in the third round in the 1982 draft. With a record of 17-8, he led the American League in ERA (2.76), WHIP (1.057), and fewest hits per nine innings (7.2) by a starting pitcher. He won The Sporting News Pitcher of the Year honors and finished second to Boston Red Sox ace Roger Clemens for the American League Cy Young Award. Key’s achievements were tremendous but were overshadowed by the devastating collapse of the Blue Jays during the final week of the season. A seven-game losing streak to end the season cost the team the American League East title to the rival Detroit Tigers. Key pitched in the final game with the season on the line and was masterful, going eight innings and giving up three hits with eight strikeouts. The problem was that one of those hits was a home run by Tigers outfielder Larry Herndon to help beat the Blue Jays 1-0.8

From 1988 to 1990, Key continued to be an essential piece of the Blue Jays’ starting rotation, but he began to battle injuries that required him to miss time. During the 1988 season, Dr. James Andrews performed surgery to remove bone chips. This cost him several months, and Key regularly pitched through injuries during the 1989 and 1990 seasons.

As the Blue Jays pushed for a playoff spot in 1991, ace Dave Stieb suffered a season-ending injury in May when a herniated disk was aggravated by a collision.9 However, a fully healthy Key was able to step up and deliver a season that was more in line with his breakout 1987 season. He had 33 starts, 16 wins, and a 3.05 ERA and was selected to his second All-Star Game. The game was played in Toronto and Key got the win, pitching a scoreless top of the third inning after which his teammates scored three runs in a 4-2 victory. His success didn’t translate into the Blue Jays winning the American League pennant. In Game Three of the Championship Series, with the Series tied at one win apiece, Key allowed two earned runs in six innings; however, the Twins won in extra innings, 3-2. The Jays lost the next two games and the Series, four games to one.

After another disappointing playoff performance, the Blue Jays used the offseason to acquire multiple pieces to solidify an already strong team. One of those acquisitions was 1991 World Series MVP Jack Morris, who had beat Toronto twice in the ALCS. The addition of Morris, the emergence of young right-hander Juan Guzman, and the late-season acquisition of New York Mets ace David Cone seemed to push Jimmy Key to the back end of the rotation. He started a full complement of 33 games, though, finishing 13-13. The Blue Jays repeated as American League East champions and faced the Oakland Athletics in the ALCS.

The Blue Jays exorcised past playoff demons and won the ALCS. However, the durable and most successful left-handed starting pitcher in Blue Jays history was not part of the rotation. Key provided three scoreless innings out of the bullpen. After Toronto clinched the ALCS, Key told TSN broadcaster and former teammate Buck Martinez, “You know me, Buck, I want to be there; it is tough for me to watch, as I told them before, as long as we win, I don’t care what we do. Never been to a World Series, and I would love to pitch; I hope they give me a chance.”10

Key would get his wish. Manager Cito Gaston named Key his starter for Game Four of the World Series vs. the Atlanta Braves with the Blue Jays up 2-1 in the Series. Key faced Braves left-hander Tom Glavine. He would also face the team managed by his first manager, Bobby Cox. After giving up a leadoff single to Otis Nixon, Key showcased his excellent pickoff move that electrified the crowd and settled down the longtime pitcher. Key pitched his best playoff start as a Blue Jay, going 7⅔ innings and allowing five hits and one run, with six strikeouts. As he left the mound, Key tipped his cap to a sold-out SkyDome. “I didn’t think much about it when I was pitching. But when I was walking off with the crowd cheering and stuff, that’s why I tipped my hat, because it might be the last time I pitch here,” he said.11 The Blue Jays won this game and took a commanding 3-1 lead in the Series.

Key wasn’t finished. He entered Game Six in relief with the game tied 2-2 in the bottom of the 10th. He induced two groundouts and got out of the inning. Dave Winfield doubled in two Blue Jays runs in the top of the 11th. Key gave up a leadoff single and saw the second batter reach on an error. With runners on first and third with nobody out, Rafael Belliard sacrificed to put two in scoring position. Brian Hunter pinch-hit for the opposing pitcher, grounding out to first base unassisted and one run scored. Mike Timlin took over for Key and secured the final out. Key was the winning pitcher for the World Series-clinching game. The longtime Blue Jay, who was part of the previous playoff collapses, said, “I’ve been through everything here. This is special. This meant a lot”12

Key entered the offseason as a free agent for the first time. Several highly regarded pitchers were free agents, including teammate David Cone, Greg Maddux, Doug Drabek, and Greg Swindell. Typically, Key wasn’t the flashiest free agent and was overshadowed by the others. He remained interested in returning to the Blue Jays, but the club had a policy of not signing a pitcher beyond three years.

The New York Yankees, who were turned down by other top names, turned their attention to Key, who was a favorite of the Yankees owner, George Steinbrenner. “I think Key is a guy I would have wanted as much as anybody,” Steinbrenner said.13 New York offered a fourth year, but Key wanted to let Blue Jays general manager Pat Gillick have a final opportunity to negotiate the deal. However, Gillick never called back and, while on a cruise to Hawaii, Key decided to sign the agreement with the Yankees. His career with the Blue Jays was over.14

Key negotiated a four-year, $17 million deal with the Yankees (and four years later another contract with Baltimore Orioles). At the time, it was reported that his wife, Cindy, who had a business administration degree from Clemson, had helped negotiate the deal.15 In 2022, Key said he had negotiated the deal himself but that Cindy had been an agent “on paper” in order to save an any agent fee.16

Key always wanted to play for the Yankees or Dodgers and had his opportunity with the Yankees for the next four years. Some people wondered how he would adjust to the pressure of New York. Cindy Key believed his makeup as a pitcher and person made the fit perfect: “Because he doesn’t have an overpowering fastball and isn’t intimidating in that way, he compensates with location. In order to have great location, he can’t be overly excited, or he’ll lose it. A long time ago, he learned the only way he’d make it to the major leagues is by control. That really made him into the player he is.”17 Key’s even-keel approach on the mound and personality was a perfect fit for the stress and bright lights of the big city.

Key proved his wife right with his dominant performance over the 1993-1994 seasons. He won his second Sporting News Pitcher of the Year Award (1994), was selected to both All-Star squads (and was the starter in 1994), and finished in the top five in Cy Young Award voting each year and received MVP votes, placing 11th in 1993 and sixth in 1994. Key was enjoying some of the best seasons in his career. However, everything changed in 1995.

In May 1995 Key was placed on the disabled list with a bout of tendinitis that ultimately required season-ending left rotator cuff surgery. There was some concern about how he would bounce back the next season.18 Key struggled to regain his form, going 2-6 with a 7.06 ERA in 10 starts to open the 1996 season. The Yankees sent him to Florida to rehab, and Key was placed on the disabled list again, this time with a strained calf. He returned from the disabled list and from June 26 to the end of the season he was 9-5 with a 3.67 ERA. Key pitched for the Yankees in the 1996 World Series, his first since leaving the Blue Jays. Again, he was tasked with facing the Atlanta Braves, a team he cheered for as a child,19 and facing Greg Maddux in both his starts. After losing Game Two, 4-0, in six innings of work, Key was given the ball in Game Six, and his grittiness was on full display. He didn’t dominate the Braves but pitched 5⅓ innings of one-run ball to help the Yankees win their first World Series in 18 years.

Just as he did after winning his first World Series with the Blue Jays, Key became a free agent again after the 1996 World Series, and signed a two-year deal with the Baltimore Orioles. He had a successful 1997, winning 16 games and helping the Orioles to an American League East title, but again experienced injuries and ineffectiveness in 1998. Key announced his retirement after the 1998 season.20

In 2009 Key was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, joining other former major-league players like Ozzie Smith, Hank Aaron, Don Sutton, Willie McCovey, and Willie Mays.21 Having retired to Florida, he joined the amateur golfing circuit. During the PB Kennel Club County Amateur Championship in Palm Beach in July 2014, Key explained his transition to golf: “The nerves and stuff helps a little bit having pitched in big games with some big crowds. Golf is a different animal; you are out there by yourself, you have got nobody to help you if have bad shots, you just have to find it and go hit it again. A lot of it is just believing in yourself and knowing you can do it. Whether it is baseball or golf, you have to have that belief.”22

Key played in amateur golf tournaments for 15 years. In April 2022 he said, “I have been spending family time with my wife of 15 years, Karin (second wife) and our two children, Jenna

and James. With Karin’s help, I have been focused on getting them started in their life’s journey.”23

Jimmy Key remains one of the most successful Blue Jays pitchers. He won between 12 and 17 games for the Blue Jays for eight consecutive years, from 1985 to 1992. His 3.42 ERA as a Blue Jay is tied with Dave Stieb for the best by a starter, and he – with 116 wins to his credit – is the winningest left-hander in Toronto history.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the following:

Mopupduty.com

Pinstripealley.com

Bluebirdbanter.com

Blue Jays 1986 Program Book

Bluejays.com

Cooperstownersincanada.com

Notes

1 Jack Curry, “Jimmy Key: The Man in Control,” New York Times, June 26, 1994: A12.

2 Brian Hennessy, “Nine Former Greats to Be Inducted into Clemson Hall of Fame,” clemsontigers.com, September 10, 1999. https://clemsontigers.com/nine-former-greats-to-be-inducted-into-clemson-hall-of-fame-2/.

3 Hennessy.

4 Hennessy.

5 Baseball America, https://www.baseballamerica.com/players/19721/jimmy-key/.

6 He pitched a third of an inning, facing one batter in the top of the third – Graig Nettles – who fouled out to the third baseman.

7 Al Widmar, Baseball Digest, March 1988, Quoted at BaseballAlmanac.com, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/trades.php?p=keyji01.

8 Gare Joyce, “The Fall of ’87,” Sportsnet Big Reads, sportsnet.ca. https://www.sportsnet.ca/baseball/mlb/big-read-inside-biggest-collapse-toronto-blue-jays-history/.

9 Graham Womack, “Dave Stieb on Hall of Fame: ‘I surely Did Not Deserve to Be Just Wiped Off the Map,’” The Sporting News, February 21, 2017. https://www.sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/dave-stieb-stats-hall-of-fame-case-interview-toronto-blue-jays-jmlb/15lhsyein7hj116xw137h58urx.

10 Buck Martinez interview with Jimmy Key, “Classic TSN: Blue Jays Post Game 1992 ALCS,” YouTube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xPLqiGUGG-Q&t=307s.

11 Thomas Boswell, “The Key to Toronto,” Washington Post, October 22, 1992: D1.

12 Boswell.

13 Jack Curry, “Yankees Finally Get It Right and Land a Lefty,” New York Times, December 11, 1992: B7.

14 Jack Curry, “Jimmy and Cindy Key Are Co-stars in ‘Honey, I Blew Up Your Salary,’” New York Times, January 24, 1993: A4.

15 “Jimmy and Cindy Key Are Co-stars in ‘Honey, I Blew Up Your Salary.’”

16 Jimmy Key email to Bill Nowlin, April 7, 2022.

17 Jon Heyman. “While Key Pitches, His Wife Controls Money in the Family,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1993: 3.

18 Jack Curry, “Key Is Out for the Season, and Possibly Longer,” New York Times, July 4, 1995: A39.

19 Jerry Felts, “Huntsville Native Gets Good News,” Huntsville (Alabama) Times Daily, October 18, 1992: 6B. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=4E4eAAAAIBAJ&sjid=TMcEAAAAIBAJ&pg=4377,2626345.

20 “Key Retires After 15 Seasons,” CBSNews.com, January 29, 1999. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/key-retires-after-15-seasons/.

21 “James Edward ‘Jimmy’ Key,” Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. https://www.ashof.org/inductees/jimmy-key/.

22 “Jimmy Key Mastering Game of Golf,” WPTV News, July 12, 2014. YouTube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4yX07ziB9U.

23 Jimmy Key email to Bill Nowlin, April 7, 2022.

Full Name

James Edward Key

Born

April 22, 1961 at Huntsville, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.