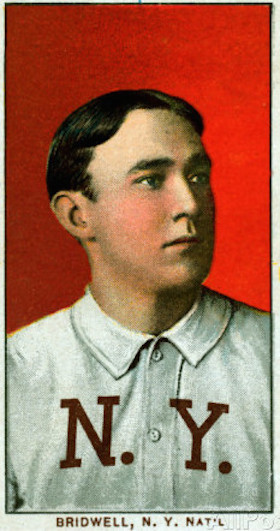

Al Bridwell

“There was never a more graceful player than Bridwell.” — Sportswriter Sam Crane, 19101

Al Bridwell was a natural in the field, one of finest defensive shortstops of the Deadball Era. Hitting did not come naturally to him, but as a member of the New York Giants, he became a solid hitter under the tutelage of manager John McGraw. In his prime, Bridwell was “regarded as being right in the Hans Wagner–Joe Tinker class of shortstops.”2

Al Bridwell was a natural in the field, one of finest defensive shortstops of the Deadball Era. Hitting did not come naturally to him, but as a member of the New York Giants, he became a solid hitter under the tutelage of manager John McGraw. In his prime, Bridwell was “regarded as being right in the Hans Wagner–Joe Tinker class of shortstops.”2

Albert Henry Bridwell was born on January 4, 1884, in Friendship, Ohio. He was the youngest of the 10 children of Samuel F. and Mary Ann (Webb) Bridwell.3 The family moved to Portsmouth, beside the Ohio River, in 1888.4 Samuel was a common laborer.5 To help make ends meet, Al quit school at the age of 13 and worked in a shoe factory.6 In his time off, he played baseball on local teams. He played against and admired Branch Rickey, who was two years older.7 A shortage of level ground in Portsmouth meant games were often played on dry riverbeds. A flash flood interrupted one game, forcing the players and umpire to swim to shore.8

As a member of the semipro Portsmouth Navies, Bridwell played against the Columbus (Ohio) Senators of the American Association in the fall of 1902. Bobby Quinn, the Senators’ business manager, was impressed and offered him a contract.9 Bridwell played 28 games at shortstop for Columbus in 1903 before going in June to the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association.10 In 81 games for Atlanta, he hit only .196. He returned to Columbus for the 1904 season and batted .264 in 151 games. His fielding caught the eye of Garry Herrmann, president of the Cincinnati Reds. “He is the fastest man on the infield I ever saw,” said Herrmann.11 The Reds acquired him in August 1904. In his major-league debut, on April 16, 1905, Bridwell smacked a pinch-hit single off Chick Robitaille of the Pittsburgh Pirates.12

Bridwell stood 5-feet-9 and weighed 170 pounds. He batted left-handed and threw right-handed. The Reds used him as a utilityman in 1905, and he hit .252 in 82 games. “For a beginner, he did well,” said Sporting Life.13 The Reds traded him, and in 1906, he was the starting shortstop on the last-place Boston Beaneaters. Bridwell showed great range in the field but was weak at the plate, with a .227 batting average and only 10 extra-base hits in 459 at-bats.

Bridwell led NL shortstops in fielding percentage in 1907. Sporting Life said, “He covers lots of ground, makes no end of hair-raising stops, following them up with fine throws, and his work is clean and finished.”14 However, he batted only .218. Manager John McGraw of the Giants felt Bridwell possessed the best throwing arm in the league15 and believed he could turn him into a hitter. The problem, McGraw said, was that Bridwell held his elbows too close to his body at the plate.16 The Giants acquired him in a trade, and McGraw worked with him on his hitting at spring training in 1908.17

The work paid off. Bridwell’s .285 batting average in 1908 ranked eighth in the league. McGraw called him “the sensation of the year in the National League.”18 On September 8 Bridwell lashed an 11th-inning walk-off single to give Christy Mathewson and the Giants a 1-0 victory over the Brooklyn Superbas.19 Against the Chicago Cubs on September 23, with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, Bridwell lined what should have been a game-winning hit, but Fred Merkle failed to advance from first base to second and was declared out. “Merkle’s boner,” one of the most infamous blunders in baseball history, was costly to the Giants in a tight pennant race. Bridwell wished he had struck out in that at-bat and spared Merkle the grief he endured for this mistake.20

After Bridwell missed a sign in a game, McGraw chewed him out and called him names. Bridwell, who was an accomplished boxer, punched McGraw, causing him to tumble down the dugout steps. Bridwell said:

“He suspended me for two weeks without pay, but once it was over he forgot about it completely. Never mentioned it again. He was a fighter, but he was also the kindest, best-hearted fellow you ever saw. I liked him and I liked playing for him.”21

On July 17, 1906, Bridwell married Margaret Lorraine McMahon,22 and the couple resided in Portsmouth. They enjoyed hunting and were said to be “crack shots.”23 Giants outfielder Fred Snodgrass related this anecdote about Bridwell and Giants pitcher Bugs Raymond:

“I remember once, in spring training, we all went to a fish fry on the final day before leaving camp. Somebody brought along a couple of target guns, and we were all shooting at targets. Bugs said, ‘Here, hit this.’ And he took out his pocket watch, a very good watch that had been given to him in the minor leagues. I remember Al Bridwell was shooting at the time. Bugs threw the watch up in the air, and Al put a bullet right through the middle of it!”24

In 1909 Bridwell batted a career-high .294, fifth best in the league, and stole a career-high 32 bases. He struck out only 15 times in 476 at-bats, the best ratio in the league. And he continued to shine at shortstop:

“His spectacular fielding has pulled many a game out of the fire, when a hit would have resulted in either a tie-up or the winning tally. … His throwing is snappy and he shoots the ball to the bases on a line as true as a rifle bullet. … He is over the entire left section of the field during a game. The stands have no terrors for him, for he will rush up to the box seats and lean over to make a catch of a foul fly.”25

Bridwell was clever. One day he outsmarted Cubs shortstop Joe Tinker:

“Bridwell was on first base when someone made a hit. The hit was short and sharp, and there was small chance for him to go to third on it. He turned second at full speed. Tinker was watching him and placed himself exactly on the route Bridwell would have to traverse to reach third, and then turned his back to make himself appear innocent of intent to interfere. His object was to make Bridwell turn wide to pass around him and lose perhaps three or four steps in distance. Bridwell saw the move. He also saw that it was hopeless to try to reach third. Instead he turned second at top speed, dashed up the line, bumped Tinker, grabbed him and fell. In an instant he scrambled to his feet and shouted to the umpire, who turned just in time to see the two men struggling to their feet. Naturally he supposed Tinker had interfered. He let Bridwell go to third – and he scored on a fly and won the game.”26

On June 13, 1910, Bridwell went 3-for-4 facing Mordecai Brown and scored both runs in the Giants’ 6-2 loss to the Cubs, and he fielded 11 chances without error. Sportswriter E.H. Simmons remarked:

“His playing on short today is unexcelled, if, indeed, it is equalled by any man in either of the two big leagues. He is the most graceful player the writer has ever seen. He is also the best natured and most gentlemanly.”27

Bridwell was not always gentlemanly. He was ejected from 12 games during his major-league career.28 The Pittsburgh Press described one of the incidents, which occurred on July 14, 1910:

“Bridwell struck out, and didn’t like [umpire Hank] O’Day’s decision on the third strike. He hurled his bat in the direction of the official, and then rushed at him as if he intended to strike him. Hank ordered him from the game, but he refused to go, and again advanced toward the umpire. [Giants third baseman Art] Devlin stepped in front of him, and shoved the irate player back.”29

In another incident, Bridwell earned a three-day suspension for throwing dirt on “O’Day’s near-bald noodle.”30

In 1911 Bridwell was slowed by leg injuries.31 McGraw thought his shortstop’s best days were behind him and traded him in July to the Boston Rustlers. The trade seemed to revive Bridwell, and he batted .291 in 51 games for Boston. The Giants went on to win the NL pennant without him, but they gave him “one-half a regular share” of the World Series proceeds.32

While working in his garage in February 1912, Bridwell stepped on a rusty nail. He contracted a serious case of blood poisoning, and it appeared he might never again play baseball, but he returned to the ball field in early August.33 His bases-loaded double gave Boston a 6-5 victory over Cincinnati on August 8.34

Young Rabbit Maranville was seen as Boston’s future shortstop,35 so Bridwell was sold to the Cubs in December 1912. The Cubs traded Joe Tinker to the Reds and counted on Bridwell to replace him. He welcomed the opportunity but left his new team in the spring of 1913 to rush home to Portsmouth. “At least 428 people died during the Flood of 1913,” the “greatest natural disaster in Ohio history.”36 After the waters subsided, Bridwell was preoccupied with “shoveling mud out of his house.”37 He and his wife were fortunate; “several of his relatives lost practically all they possessed.”38

Working alongside Johnny Evers, the Cubs’ second baseman and manager, Bridwell recorded a career-high .948 fielding percentage in 1913. In a victory over the Pirates on April 28, he made two standout plays:

“Bridwell robbed [Jack “Dots”] Miller of a hit in the third by leaping high into the air and pulling down Jack’s liner. He easily doubled [Bobby] Byrne at second. In the ninth Al ran back of the keystone sack and deprived [Arthur “Solly”] Hofman of a single by scooping Artie’s hard grounder and quickly lining the ball to [Vic] Saier [at first base].”39

On June 8 McGraw surely regretted trading Bridwell, as the Cubs defeated the Giants, 2-1, in 10 innings.

“The reason was that Al baldly stole the game from New York. … Twice in the ninth inning Al turned loose speed that would have looked fair beside a ten-second runner. He rushed in and scooped a wicked roller with his immodest hand, hurling a runner out at first. … On the next ball hit Al shagged behind second base and gloved the pill, turning quickly to peg to Saier for the third out.”40

“Bridwell is not fluking. He is pulling the same fast stuff every day, making quick pick-ups and throws from awkward positions and getting his share of bingles. Few of his hits travel for extra bases, but any of the opposing pitchers will tell you that Bridwell in a pinch is one of the most dangerous men in the National League at bat.”41

Mary Jane, the only child of Al and Lorraine Bridwell, was born in January 1914.42 Al received a 50 percent pay raise by playing for the St. Louis Terriers of the Federal League in 1914 and 1915,43 but those were his last major-league seasons. He played for the Atlanta Crackers in 1916 and 1917. He was invited to spring training in 1918 with the Columbus Senators, managed by Joe Tinker, but left after a few days and returned home to Portsmouth, where he worked as a munitions inspector during World War I.44

Bridwell managed the 1919 Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League; Branch Rickey had recommended him for the job.45 When the team needed an outfielder, “Bridwell leaped into the lineup in the left field and has been grabbing long flies, chucking men out at the plate and whacking the ball with a right good will.”46 Over the next five seasons, he managed and/or played for teams in Rocky Mount, North Carolina; Spartanburg and Charleston, South Carolina; Oneonta, New York; and Tamaqua, Pennsylvania.47 He retired from baseball in 1924, at age 40.

After his baseball career, Bridwell was sheriff of Scioto County, Ohio, and later a company policeman employed by the Wheeling Steel Corporation in Portsmouth.48

Bridwell followed major-league baseball into his 80s. In the 1960s he said:

“A lot of people will tell you that the modern player can’t compare to the old timer. Not even in the same league, they say. Well, maybe they’re right, but I don’t think so. I don’t think there’s ever been a better outfielder than [Willie] Mays, or a better left-handed pitcher than Sandy Koufax, or a better third baseman than Brooks Robinson, just to name three that are playing today.”49

Looking back on his baseball career, Bridwell said: “I don’t really think I’d change a thing. Not a thing. It was fun all the way through. A privilege, that’s what it was, a privilege, to have been there.”50 On January 23, 1969, the slick-fielding shortstop died at the age of 85, in Portsmouth.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the pioneering work of Larry Ritter, who interviewed Al Bridwell and other former ballplayers in the 1960s. Ritter’s masterpiece, The Glory of Their Times, continues to inspire the author.

Notes

1 El Paso (Texas) Herald, August 20, 1910.

2 Washington Times, August 8, 1910.

3 Ancestry.com.

4 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It (New York: Vintage Books, 1985), 125.

5 1880 and 1900 US Censuses.

6 Ritter, 128.

7 Ritter, 125.

8 Chicago Daily Herald, April 14, 1911.

9 Ritter, 126.

10 Sporting Life, June 20, 1903.

11 Sporting Life, November 5, 1904.

12 Sporting Life, April 22, 1905.

13 Sporting Life, November 11, 1905.

14 Sporting Life, June 1, 1907.

15 Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, January 30, 1908.

16 Sporting Life, January 18, 1908.

17 Altoona Tribune, March 19, 1908.

18 Sporting Life, September 12, 1908.

19 New York Times, September 9, 1908.

20 Ritter, 132.

21 Ritter, 131.

22 Ancestry.com.

23 Sporting Life, January 2, 1909.

24 Ritter, 96–97.

25 Altoona Tribune, September 1, 1909.

26 Kingston (New York) Daily Freeman, August 9, 1915.

27 Sporting Life, June 25, 1910.

28 Retrosheet.org/boxesetc/B/Pbrida101.htm.

29 Pittsburgh Press, July 15, 1910.

30 Chicago Day Book, August 20, 1913.

31 Salt Lake Tribune, August 20, 1911.

32 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 28, 1911.

33 Sporting Life, March 16, 1912; Pittsburgh Press, May 16, 1912; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 2, 1912.

34 Boston Globe, August 9, 1912.

35 East Liverpool (Ohio) Evening Review, November 13, 1912.

36 Ohiohistorycentral.org/w/1913_Ohio_Statewide_Flood?rec=497.

37 Pittsburgh Gazette Times, April 9, 1913.

38 Chicago Inter Ocean, April 11, 1913.

39 Chicago Inter Ocean, April 29, 1913.

40 Chicago Day Book, June 9, 1913.

41 Chicago Day Book, July 5, 1913.

42 Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, January 23, 1914; 1920 and 1930 US Censuses.

43 Ritter, 131.

44 Indianapolis News, May 2, 1918; World War I draft registration.

45 Houston Post, March 16, 1919.

46 Houston Post, August 16, 1919.

47 Waco (Texas) News-Tribune, July 9, 1921; Oneonta (New York) Star, February 26, 1923; Shamokin (Pennsylvania) News-Dispatch, February 16, 1924.

48 Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, July 20, 1931; World War II draft registration.

49 Ritter, 124–125.

50 Ritter, 132.

Full Name

Albert Henry Bridwell

Born

January 4, 1884 at Friendship, OH (USA)

Died

January 23, 1969 at Portsmouth, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.