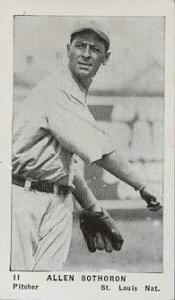

Allen Sothoron

Al Sothoron was a spitball pitcher and a master of trick deliveries. When the moist pitch was outlawed, Sothoron was one of 17 practitioners of the art who were exempted from the ban under a grandfather clause. Whether he continued to use other trick pitches, some of which were now illegal, is a matter of conjecture. For 15 years he hurled his pitches, wet or dry, in the majors and minors until he left the mound to become a coach and manager.

Al Sothoron was a spitball pitcher and a master of trick deliveries. When the moist pitch was outlawed, Sothoron was one of 17 practitioners of the art who were exempted from the ban under a grandfather clause. Whether he continued to use other trick pitches, some of which were now illegal, is a matter of conjecture. For 15 years he hurled his pitches, wet or dry, in the majors and minors until he left the mound to become a coach and manager.

Allen Sutton Sothoron was a native of Bradford, a small city in western Ohio, on the Darke side of the line which splits Bradford between Darke and Miami counties, north of Dayton and about 20 miles east of the Indiana state line. He was born on April 27, 1893, a son of Ida and Bernard Sothoron, a tinner employed by a local hardware store. In 1912, Allen played baseball for Juniata College in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania.1

The young man started his professional career as an outfielder, playing for both Troy and Binghamton in the Class B New York State League in 1912. The following season he played for York in the Tri-State League and Columbus in the South Atlantic, before taking the mound for Fall River in the New England League. He split the 1914 and 1915 seasons between the St. Louis Browns and two minor league clubs.

Sothoron made his major league debut for the St. Louis Browns on September 17, 1914. He entered the game in the top of the fourth inning with the Washington Nationals leading the Browns 8 to 2. The Washington Post reported: “Rickey introduced young Southern [sic] just up from the bushes. He just arrived yesterday. Southern went along well enough for five of the six innings that he slabbed. But in the seventh the Nationals took a sudden and fond liking for his offerings and hammered out four more runs.”2 In all Sothoron gave up six hits and four runs. He walked four and struck out three in his only appearance of the season, as the Browns went down to a 12-2 defeat.

(The New York Times also spelled Allen’s name Southern in its report of the game. Some sources still misspell his first name as Allan, although he himself consistently spelled it as Allen in documents, such as his draft registration, passport application, and marriage license.) In 1915 Al appeared in three major league games, losing his only decision.

After two brief, unproductive major league trials, Al was assigned by the Browns to the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League in 1916. Out west for the first time, he had his first winning season, and it was a dandy. A sportswriter for the Los Angeles Times was impressed by Al’s pitching. After one game in June he wrote: “Sothoron, running true to a peculiar habit which he has, allowed only three hits and was strongly opposed to anybody getting further than second base. He believes that base-runners should be confined to the southwest side of the diamond.”3

By August 1916 he had a 15-15 record; then he reeled off win after win. On October 21 he shut out Los Angeles 6-0 for his 15th consecutive victory and his 30th win of the season. He was just one game short of the league record for consecutive wins, but he lost his last two games and did not break the record. However, he led the league in wins and in shutouts, and was second in strikeouts, just one behind the league leader.4

This fine performance earned him another shot at the majors, and this time he made good. During spring training he told manager Fielder Jones, “Mr. Jones, I’m going to give you the correct dope on me right at the start. I’m not like Groom and others who get into shape in a few days. I need three weeks at least and I like that sun”5 However, the other pitchers did not get in shape. On the opening day of the season, Sothoron again approached his manager: “Mr. Jones, my arm isn’t as good as it’s going to be in May and June, but I’m ready to go out and do the best I can right now with the other boys sitting. Call upon me any time.”6

Jones called on Sothoron twice during the first week of the season. In his first appearance he relieved Ernie Koob in the sixth inning and preserved a 3-1 win over the Chicago White Sox. A few days later he rookie pitched a complete game masterpiece. Only a fourth inning single by Ray Chapman prevented a no-hitter, as Allen set the Cleveland Indians down on one hit. He struck out one, walked two, and saw one Clevelander reach base on an error, as he shut out the Tribe 4-0.

Suddenly, the rookie was a sensation. Newspapers reported the young man is “22 years old, 5 feet 11 inches tall, weighs 172 pounds, and has an assortment of stuff that will make him a star. He uses a fast ball, a curve, a show ball, a side arm, an underarm and then he mixes this stuff with a spitter. The wet delivery is used only in the tight places when someone is close to scoring.”7

By July his manager was singing the young man’s praises: “Sothoron is going to surprise a lot of people before the year is out, because he is going to be the champion pitcher of the American League. In my mind he is the nearest thing to Ed Walsh I have seen since Ed dropped out. For his age he is a remarkable pitcher. That right arm of his is as strong as a piece of steel. He is a cool-headed chap, which is saying a great deal for a pitcher. He has good control of the spitter and he doesn’t waste many. Give him a few months of active work and you can take it from me that he will reach the great heights once held by Big Ed. He has it in him to make good. He’s a natural-born player. Nothing vexes him in action. They can kid and josh him all they want. He comes back for more.”8

For the remainder of 1917, Al pitched reasonably well, as attested by his 2.83 earned run average, but received little support from his teammates. He and fellow Brownie pitcher Bob Groom tied for the league lead with 19 losses each as the St. Louis club finished seventh in the American League. The United States entered the World War in 1917. Soon baseball players were volunteering or being drafted into the armed services. Although he was a single man, Sothoron was placed in the deferred class by his draft board.9

In 1918 Sothoron improved his ERA to 1.94, third best in the league, and broke even in the won-lost column. Dixie, as he was called because his frequently mispronounced name led people to think he was from the South, held opponents to a .205 batting average, lowest in the league. Among American League pitchers he held opponents to the second lowest on-base percentage and allowed the third fewest base runners per nine innings. When Secretary of War Newton Baker issued his “work or fight” order, Sothoron chose work. He got a job in a plant in Dayton and played in that city’s Triangle Factory League.10 In September George Ketchner, a former major league scout, approached Sothoron with an offer of a job with the Bethlehem Steel Company if he would play for the company’s team in the Steel League. However, Al elected to remain in Dayton.

In 1919 Al had his most successful season ever in the major leagues, winning 20 games and posting a fine 2.20 earned run average. He tied for fifth in the number of wins and had the fifth best ERA in the league. He had the third best weighted rating and tied for fifth in the Faber System rankings. It appeared that he was on his way to fulfilling Fielder Jones’s expectations.

However, actions of the joint rules committee of the major leagues knocked Sothoron’s express off the tracks. On February 9, 1920, the committee banned the spitball and other so-called “freak deliveries.” Each American League club was allowed an exemption from the spitball ban for not more than two hurlers for the 1920 season. The Browns had three spitballers—Sothoron, Urban Shocker, and Bert Gallia. General manager Bob Quinn and the new field manager, Jimmy Burke, chose to use the St. Louis exemptions for Shocker and Gallia. Quinn thought Sothoron impaired his real value to the team by monkeying around with the spitter.11 Al’s catcher, Josh Billings, suggested Sothoron would be a better pitcher because of the ban on trick deliveries. Al was described as an inventive genius, always perfecting some new freak pitch, much to the distress of his catchers, who had to be the butt end of his experiments.12

Sportswriter Fred Turbyville joined those thinking Sothoron could survive the rule change. Writing that you can’t keep a good man down, the scribe penned, “They’ve taken all his tricks away from him, but he’ll come back with something else. He is young and his arm is as good as it ever was. His brain is better. So just watch for Allan Sothoron to wind up the season of 1920 with another good record.”13

The man himself thought he could survive without the spitter. He opined that the new rule prohibiting freak deliveries would not prevent him from throwing pitches that sailed. He said that as soon as the ball is hit, the bat leaves a mark on the smooth cover of the ball, and this one bruise will enable the pitcher to use the spot in throwing a ball that comes up so mysteriously that the batters imagine it is floating up to them. He thinks he will be able to throw the shine ball without rubbing it on his uniform. If the batsmen think they are going to have an easier time making base hits this year, they are mistaken, he said.14

As it turned out, Sothoron had a very bad year in 1920. After he got off to a poor start his manager got permission from American League president Ban Johnson to substitute Al for Bert Gallia on the exempt list. Regaining use of the spitter did not salvage the season for the pitcher. The other freak deliveries were still banned. Perhaps Al had depended on other shenanigans more than on the spitter. For example, umpires discovered that balls used by Sothoron in the final game of the 1919 season had been cut about the seams.15 Years later, Rogers Hornsby recalled that Al used to cut the seams on the bias with a razor blade and raise a wing on the ball whenever he got in a tight spot.16 A reasonable conclusion was that enhanced inspection of the baseballs in 1920 and thereafter inhibited Al from using some trick delivery that he had previously utilized successfully.

In 1920 Sothoron won only eight games, while losing 15. This was not entirely his fault. In his four full seasons with the Browns, the club never had a winning record, making it difficult for Sothoron to compile the record that his ability seemed to warrant. Another reason Al did not enjoy greater success in the majors may have been his inability to field bunts.

Charles F. Faber and Richard B. Faber wrote: “Although he was recognized by his peers as one of the smartest pitchers in all of baseball, the name of the veteran spitballer was not a household word to the fans of America. For his entire career he had pitched in relative obscurity, toiling for the lowly St. Louis Browns on the west side of the Mississippi River, far from the population centers of the East, where ballplayers gained national renown. In 1921 he got off to a poor start with the Browns. After losing two of three decisions, he was waived to the Boston Red Sox, for whom he lost both of his starts.

Then he found new life with the Cleveland Indians. What a break it was to be picked up by the defending world champions! The spitballer took full advantage of the opportunity. With the Tribe he won 12 games and lost only four, keeping the Indians in first place much of the season. It appeared he would finally get to a World Series and receive the recognition that was his due. Alas; it was not to be. The surging New York Yankees caught and then passed Cleveland to take the American League pennant. The spitballer never again enjoyed a season such as 1921. He is destined to be remembered mainly for a one-liner penned by Bugs Baer: “Allen S. Sothoron pitched his initials off yesterday.”17

One of Sothoron’s best efforts of 1921 was a three-hit shutout over the New York Yankees on July 23, which temporarily stopped the Yanks from taking over first place in their drive to their first American League pennant. Knowing of Al’s reputation for throwing freak pitches, the Yankees challenged almost every one of Sothoron’s offerings, claiming he was throwing illegal pitches, including an emery ball.18 However, umpire Brick Owens found nothing wrong with the balls.

Sothoron faced the Yanks three more times as the two teams battled for the American League pennant. On July 31, Al was knocked out of the box in the sixth inning of a 12-2 loss. On August 8, he made amends by pitching a masterful 11 2/3 innings of relief and holding the Yankees scoreless in the final nine innings of a 13-inning Tribe victory. On August 25 Al defeated the Yankees 15-1. Again the Yanks repeatedly, but to no avail, accused him of tampering with the ball.

New York was not the only club to accuse Al of doctoring the ball. There were more complaints in 1921 about Sothoron than about any other pitcher.19 Among the tricks of this master trickster was one worked by raising a corrugation on the side of the ball without the aid of any foreign substance. By the use of a strong forefinger and thumb Sothoron would work up the seam of the ball until it stood out. Then the pitch would act much like the outlawed emery ball that Russell Ford had used.20

Sportswriter Hugh Fullerton expressed some grudging admiration for Sothoron’s deeds: “If Sotheron [sic] has been nicking the ball he is a smart pitcher, smarter than most of us have given him credit for being….If now the pitchers are getting smart enough to cheat only when it counts, it seems a move toward the good, no matter how immoral.”21

Al’s .750 winning percentage for the Indians was not bested by any pitcher in the junior circuit that year, but his earlier losses with St. Louis and Boston brought his overall percentage down to a more modest .619. Perhaps his most outstanding accomplishment that season was pitching 178 innings without giving up a home run. No other pitcher in the post-Dead Ball Era has pitched that many innings while allowing no homers.22

After getting off to a poor start in 1922, Sothoron was released by the Indians. He pitched for Louisville of the American Association in 1923 and returned to the majors with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1924. Upon his purchase by the Cardinals, a sportswriter for the Washington Post reviewed his career, putting special emphasis on his difficulty fielding bunts.

The article stated: “Al Sothoron, bunted out of the American League in 1922, is headed back for the big time again, and irrespective of his ultimate fate, the psychology students in the ranks of fandom will have something to mull over, for Sothoron, once one of the best right-handers in the business, was the victim of nothing more or less than a mental hazard, or at least, so it seemed. Four years ago when freak pitching was in its glory, Sothoron, a spitballer and master trickster, ranked with the greats of the flinging fraternity….Then, around the half-way mark of the 1920 campaign in the closing innings of a tight game at Cleveland…the pitcher, fielding a bunt, chucked the ball into the stands, for the Indians’ margin of victory. From then on it became a habit, and Sothoron’s appearance in the box was the signal for a concerted bunting attack by the enemy that always wound up in the same way—wild heave and early exit.23

According to the Post article, Sothoron’s difficulty fielding bunts led to a temporary end to his major league career and even plagued him at Louisville. The writer thought that Branch Branch Rickey’s mastery of psychology might enable him to get the spitballer back on the track even after three other managers had failed. Perhaps Rickey’s magic worked for a while. Al made no errors in 1924. However, his fielding average plummeted to .864 in 1925 and a mind-boggling .778 in 1926. His career fielding average of .871 was by far the worst of any of the spitball grandfathers.

Sothoron won ten games for the Redbirds in both the 1924 and 1925 seasons. In 1926 he won only three games for the Cardinals, but one of his victories was crucial to the Redbirds winning their first National League pennant. In late August the Cards were locked in a tight race with Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. On the morning of August 31 the world champion Pittsburgh Pirates were in first place, Cincinnati was second, and St. Louis third, only a few percentage points behind the leaders. In the day’s action the Reds lost to the Cubs, and St. Louis moved into first place by sweeping the Pirates in a doubleheader. Sothoron won the nightcap 2-1 with a masterful performance, holding the champs to only three hits. Al went the route for his only complete game of the season. For the first time in their history the Cardinals entered September in first place. They held on, of course, to cop their first National League flag. However, Sothoron did not get a chance to pitch in the Cards’ World Series triumph over the Yankees that October. Apparently, he remained on the bench or in the bullpen throughout the series. Al wound up his major league pitching career at the end of the 1926 season, but he was not through with baseball yet.

Following the end of his playing career Al stayed with the Cardinals as a coach for two years. In 1928 he signed as a coach with the Boston Braves under manager Rogers Hornsby. In 1929 Sothoron became the manager of a second division Louisville club in the American Association. The very next season he led them to the league crown.

Sothoron had been regarded as one of the cleverest pitchers in the majors. He proved to be a very intelligent manager as well. In 1930 outfielder Johnny Marcum was leading Louisville in hitting with a .395 average, but toward the end of the season the Colonels needed pitching help. Knowing that Marcum had once been a pitcher, Sothoron asked Johnny to try pitching again.24 The young Kentuckian responded with four straight wins to help the Colonels win the pennant. Marcum went on to play in the majors for seven years—as a pitcher. At Louisville Sothoron earned a reputation as a great teacher of young players. Although Louisville did not repeat as league champion, Al had shown enough managerial acumen to earn another chance in the major leagues. In 1932 he became a coach for the St. Louis Browns.

On July 19, 1933, with the Browns in last place and in financial difficulty brought on by the Great Depression and aggravated by their own lack of competitiveness, Bill Killefer resigned as St. Louis manager. His good friend and coach Al Sothoron was appointed acting manager in his stead. Al knew the limitations of the team: “We have a small squad, well below the limit of 23, and there is little I can do with respect to making any changes at this time. I’ll simply try to get the most out of the material at hand and see if I can’t get the Browns in the winning habit.”25

Sothoron did not have much of a chance to instill a winning habit in the Browns. Under his tutelage the cellar-dwellers won only one of four games before Al was replaced as manager by Rogers Hornsby. The Browns had never intended for Sothoron to be a long-term manager. They employed him only as a stopgap until they could complete arrangements for Hornsby to take over. The Rajah was unable to get the Browns out of last place. The club never finished higher than sixth place during his five years at the helm.

In 1934 Sothoron became manager of the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association. He enjoyed considerable success with the Brew Crew, finishing in the first division in four of his five years as skipper. One of the problems with being a minor league manager is that your best players are likely to be promoted to a higher league. The champion 1936 Brewers were led by two powerful sluggers, Chet Laabs and Rudy York, who hit .324 and .334, respectively, and between them had 79 home runs and 299 runs batted in. Both were in the major leagues in 1937. Two of Al’s 19-game winning pitchers, Luke Hamlin and Joe Heving, were also called up, as was Clyde Hatter who went 16-6 and led the Association with 190 strikeouts. Also promoted to the majors from the 1936 team was a third baseman whom Sothoron had discovered as a teenager playing on the sandlots of Milwaukee the previous season. Ken Keltner went on to have a distinguished major league career, mostly with the Cleveland Indians. After his Brewers finished third in the 1938 season, Sothoron was released as manager, and his career in professional baseball was over.

Sothoron was married three times, but none of the unions produced any issue. His first marriage was to Madge Barlow of St. Louis. The wedding took place in Webster Groves, on October 28, 1920, the same day that Al applied for a passport to go to Cuba “on baseball business.” The couple separated on January 15, 1927, and Madge was granted an uncontested divorce on March 23 on the grounds that her husband refused to let her bring her friends into their home.26 In 1928 Sothoron married a young woman from Kansas named Harriett. The couple were living in Louisville at the time of the 1930 census. By 1937 that marriage had ended, and Al wed a St. Louis socialite, Dorothy Clemens, at St. Bartholomew’s Church in the Mound City in October of that year. The daughter of a prominent physician, Dorothy was a member of the Colony Club and the Junior League

On June 17, 1939, the former spitballer died at St. John’s Hospital in St. Louis from a complication of diseases after a three-week illness. According to Bill Lee, Al died from heart trouble, acute hepatitis, and alcoholism.27 He was buried in New York. Sothoron was only 46 years old. He was survived by his third wife, Dorothy.

This article is expanded from a chapter on Allen Sothoron in Charles F. Faber and Richard B. Faber, “Spitballers: The Last Legal Hurlers of the Wet One” (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006).

Notes

1 There is some dispute about Sothoron’s college experience. John Spalding wrote that he had attended Albion College. Baseball Almanac lists him as pitching for Albright College in 1913-14, which seems unlikely. Extensive research by Rick Benner indicated that Sothoron has played baseball only for Juniata.

Rick Benner, personal correspondence to Charles F. Faber, September 2004.

2 Washington Post, September 18, 1914.

3 Los Angeles Times, June 5, 1916.

4 John E. Spalding, Pacific Coast League Stars, Vol. 2: Ninety Who Made it in the Majors, 1903-1957., San Jose, CA: John E. Spalding, 1997, pp. 33-34.

5 Piqua (Ohio) Daily Leader Dispatch, May 9, 1917.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Fielder Jones, quoted in the Galveston Daily News, July 2, 1917.

9 Postville (Iowa) Review.

10 The Capital Times (Columbus, Ohio), August 3, 1918.

11 Olean (New York) Daily Herald, February 27, 1920.

12 Lethbridge (Alberta) Daily Herald, March 10, 1920.

13 Lowell Sun, April 21, 1920.

14 Muscatine (Iowa) Journal and News Tribune, May 5, 1920.

15 Daily Courier, Connelsville, Pa. October 17, 1919.

16 Galveston News, February 2, 1961.

17 Faber and Faber, op. cit., p. 145.

18 Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg. 1921: The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2010., p. 200.

19 Ibid.., p. 220.

20 Ty Cobb, Memoirs of Twenty Years in Baseball, p. 69.

21 Hugh Fullerton, New York Evening Mail, September 12, 1921, cited by Spatz and Steinberg, op. cit., pp. 220-21.

22 www.BaseballLibrary.com, July 3, 2004..

23 Washington Post, January 7, 1924.

24 Los Angeles Times, September 24, 1933.

25 Washington Post, July 20, 1933.

26 Iola (Kansas) Daily Register, March 22, 1927.

27 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology: The Post-Baseball Lives and Deaths of Over 7,600 MajorLeague Players and Others. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003, p. 375.

Full Name

Allen Sutton Sothoron

Born

April 27, 1893 at Bradford, OH (USA)

Died

June 17, 1939 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.