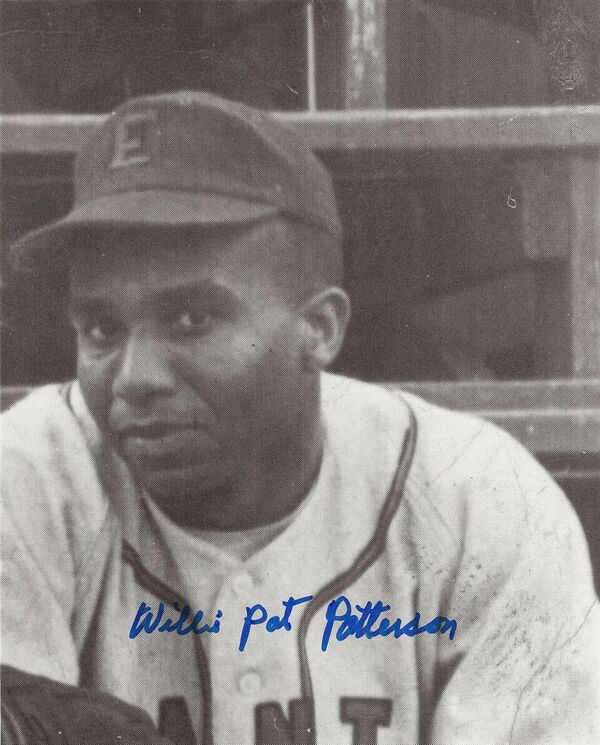

Andrew Patterson

Andrew Lawrence Patterson was born on December 19, 1911, in Chicago.1 Both of his parents died while he was extremely young, so the duty of raising the boy fell to his maternal grandparents.2 Pat, as he became known, discovered athletics early on and augmented his classroom education as a multisport athlete at integrated Washington High School in East Chicago, Indiana, just across the state line from Chicago. There he starred in football, baseball, and basketball, as well as on the track oval.

Andrew Lawrence Patterson was born on December 19, 1911, in Chicago.1 Both of his parents died while he was extremely young, so the duty of raising the boy fell to his maternal grandparents.2 Pat, as he became known, discovered athletics early on and augmented his classroom education as a multisport athlete at integrated Washington High School in East Chicago, Indiana, just across the state line from Chicago. There he starred in football, baseball, and basketball, as well as on the track oval.

After high school Patterson could have attended New York University to play football and baseball on scholarship, but he instead selected Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, just west of Shreveport, Louisiana, where he received a baseball scholarship and played all four sports as well. Patterson’s choice to move from the Chicago area to staunchly segregated East Texas was not as odd a decision as it seems. According to Negro League historian Donn Rogosin, Patterson attended Wiley College “because of the cheap tuition and the chance to play serious baseball there. … Patterson’s decision was an indication of baseball’s general preeminence at the time.”3

By 1933, the 21-year-old Patterson was a player without a team, as the Great Depression forced Wiley to cancel the entire baseball program in order to save money. In the pre-NCAA days of institutional self-governance, the school did permit players to moonlight as professionals during the summer before returning in the fall. Patterson finagled a tryout with the independent Homestead Grays. After the tryout, he returned to college and graduated with a degree in education.4

The next year, 1934, the switch-hitting Patterson earned a spot with the still-independent Grays, and also played part of the season with the Cleveland Red Sox of the Negro National League. The team posted a 4-25 record before folding. Patterson, however, proved his mettle and enjoyed fan vote selection as the sole Cleveland representative in the annual East-West All Star Game in Chicago. There, in one of the “best pitching duels in East-West All Star game history,” a game in which the sole run came in the top of the eighth inning when Jud Wilson drove in Cool Papa Bell, Patterson went 0-for-1 for the losing West squad as a late-game replacement for Sammy Hughes.5

In 1935, without a team but now with a professional reputation, Patterson caught on with Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords. There, playing alongside future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and Judy Johnson on perhaps the finest Negro League team ever assembled, Patterson held his own. In the championship series against the New York Cubans, he was 7-for-27 at the plate, but his series highlight came in Game Six. With Pittsburgh trailing three games to two and with the game tied, 6-6, in the bottom of the ninth inning, Patterson doubled off Martin Dihigo and then scored on Judy Johnson’s hit to win the game. The next day the Crawfords came all the way back in the series and won the title.

In 1935 Patterson left Pittsburgh in order to take up the nomadic baseball life with J.L. Wilkinson’s Kansas City Monarchs. The statistics for the barnstorming teams of the day are notoriously unreliable, even more than normal league numbers, yet it is generally held that Patterson was one of the best hitters in the entire Midwest. He earned his second East-West Game bid, representing Kansas City in the August 23 game, and went 2-for-3 with a double, driving in a run in the West’s 10-2 loss.6

The Monarchs often played against local white teams while on the road and, although conflict was rare during these interracial games, Patterson was involved in an unfortunate incident that presaged what black players would encounter once the integration of Organized Baseball began. In her history of the Monarchs franchise, Janet Bruce describes the incident involving Patterson:

On a barnstorming tour in Texas, infielder Pat Patterson went up in the grandstand and punched a man because of his constant name-calling. Wilkinson fined Patterson $50. “He was right for fining me,” Patterson recalled. “He explained to me, ‘That’s our policy — you just don’t bite the hand that feeds you. Those people are coming out here and see you play ball.’” And for barnstorming black teams, the paying customer could say what he pleased.7

Patterson returned briefly to Negro League play, and Pittsburgh, in 1937, but like many of his contemporaries, he fell under the spell of the money bandied about by the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo and spent most of the season playing for Águilas Cibaeñas. After the Dominican season, Patterson returned to Kansas City for another round of barnstorming and joined the Monarchs in time for an exhibition slate against a team that featured Bob Feller, Lon Warneke, Mace Brown, and Johnny Mize. Patterson went 3-for-10 in the series, but the Monarchs lost three of the four games.8

Perhaps aware that he needed a more reliable livelihood should baseball not work out, Patterson began working in the offseason as a teacher and athletic coach at Jack Yates High School in his new home city of Houston, Texas.9 As gifted Patterson was as an athlete, he was an even more talented and dedicated educator, and with the exception of three years in military service during World War II, he lived his life as an example to others of the area of the possible, even in a segregated America.

One example of Patterson’s impact on black students in segregated Texas was his role in helping to shape the Prairie View Interscholastic League into a black sports league that would provide an organizational counterpart to the white schools’ University Interscholastic League. Patterson created the organizational plan for high-school football, which he coached, and Yates principal William S. Holland met with E.B. Evans, the president of Prairie View A&M University, in the spring of 1939 in order to decide how to implement the plan the following year (1940).10 Although the days of segregation were in the past, Patterson was honored as a member of the inaugural class of the Prairie View Interscholastic Coaches Hall of Fame in 1980.11

Patterson spent the 1938-39 baseball seasons in Pennsylvania, this time with the Philadelphia Stars. After a pedestrian 1938 season, he returned the East-West game in 1939. Two East-West games were played that season, and Patterson appeared in both. He started at third base in the first iteration, on August 6 at Comiskey Park, and had a hit and stole a base in four at-bats in a 4-2 loss. In the second game, played at Yankee Stadium on August 27, Patterson went 0-for-5 but drove in a run in a 10-2 East victory.12

Patterson’s speed and ability to make contact at the plate, along with a touch of pop in his bat, were his most valuable baseball gifts, but he had intangibles as well. He “had good speed on the bases,” was considered a solid fielder, and he always hustled. While he could play every position except pitcher or catcher, he will forever be considered one of the finest third basemen in the Negro Leagues in the late 1930s and the 1940s.13

At age 28, Patterson again left the United States, this time to play with manger Ernesto Carmona’s Mexico City Diablos Rojos (Red Devils) in 1940 and 1941. He hit .341 with six home runs in 60 games in 1940, and improved to a .362 mark in 1941.14 Patterson was part of a large contingent of Negro League players who spent the season south of the border, as stars like Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, and Burniss Wright filled out Mexican rosters as well. During his time in Mexico, Patterson wed Gladys Inez Clowe, from Texas. He was such a popular player that Carmona “declared a team holiday and threw ‘a lovely party,’ according to Gladys Patterson. ‘I’d never seen a roast pig before,’ she confessed.”15 Their union produced twin sons, Andrew Jr. and Patrick, and thrived until Patterson’s death in 1984.

With his bride on his arm, Patterson rejoined the Philadelphia Stars for the 1941 Negro League season and was the team’s regular third baseman. The following season, 1942, he was moved to second base and was again selected to represent the East in both East-West games that year. Over the two contests he walked twice, stole two bases, drove in a run and scored one.16 Those proved to be the final East-West opportunities for Patterson. In six all-star games he posted four hits, including a double, drove in three runs, and stole four bases. That latter mark tied Patterson for the lead in stolen bases in East-West Games.17

With the nation at war, Patterson stepped away from baseball for three years. On December 5, 1942, he returned to Houston and enlisted in the Army Air Corps.18 Although he had earned his degree at Wiley College, he started his military career at the lowest station in the hierarchy, that of private. His official position was Athletic Instructor19 and he administered physical training at several bases in the United States. According to his family records, Patterson was awarded the American Theater Ribbon, the Good Conduct Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

After his release from active duty in 1945, Patterson returned to the classroom at Yates High School and mulled over the possibility of returning to the baseball diamond as well. Philadelphia still owed Patterson’s contract, but there was ongoing friction between Patterson and the team’s manager. Never one to miss an opportunity, Abe Manley traded for Patterson to take over third base on his Newark Eagles. “The only reason I can get Patterson,” Manley told his wife, Effa, “is because he’s not getting along with the manager. He’s one of those outstanding players that Philly wouldn’t think of giving up otherwise.”20 During the Eagles’ 1946 championship season, Patterson helped fill out an infield that included Larry Doby and Monte Irvin. In the 1946 Negro League World Series, despite leaving before the Series concluded in order to return to his primary career as a high-school teacher and coach,21 Patterson had six hits in 23 at-bats on the Eagles’ march to the title.

Patterson turned 35 in 1947 and played for three teams: Newark, the New York Black Yankees, and the Homestead Grays. His successes in baseball were coming further apart, and the demands of his persona as teacher and role model for many of Houston’s black teenagers were becoming more strident. Patterson finally chose to leave baseball, although he gave it one last go in 1949 when the Eagles relocated from Newark to Houston. After a season in which he hit only .217, he knew it was time to hang up his spikes for good.

As successful as Patterson had been as a professional baseball player, he was even better in his real profession. In 1950 he completed graduate work and earned a master’s degree in education from what was then called the Texas State University for Negroes (now Texas Southern University). In the classroom he touched countless lives, and as a coach he directly influenced several future professional athletes, including Expos outfielder Steve Henderson and Washington Redskins defensive end Leroy Brown Jr.22 Patterson continued to coach and teach at Jack Yates High School until 1967, and in 1982 became the first black coach ever named to the Texas High School Coaches Association Hall of Honor.23 After leaving Jack Yates, Patterson worked for a time as a stadium consultant for Houston’s Jeppesen (now Robertson) Stadium, and then in 1971 was appointed assistant athletic director for the Houston Independent School District.

According to his family, Patterson loved to travel with his wife, Gladys, especially after he retired from the school district, and he often said, “I just wanted to be remembered as someone who tried to help young men.”24 He exceeded that noble goal by a long measure. In the early 1980s Patterson endured a heart-valve replacement, and finally succumbed to complications from that procedure on May 16, 1984.25 He is buried alongside Gladys, who died on February 18, 2004, at the Paradise South Cemetery in Pearland, Texas, a suburb of Houston.

Limiting Patterson’s biography to only his athletic achievements would be underselling the man. He was a husband, a father, a citizen, an educator, and a role model. By coincidence, he was also a pretty darn good ballplayer.

Notes

1 Biographical data form for a reunion banquet of Negro League players, filled out by Andrew Patterson (available in the Patterson family archives).

2 Family memory; myheritage.com/person-1000001_53176192_53176192/andrew-l-patterson-sr. Accessed January 2015.

3 Donn Rogosin, Invisible Men: Life in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983), 48.

4 Ibid.

5 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 61.

6 Ibid.

7 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985), 60-61.

8 John B. Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 349.

9 Family memory; myheritage.com/person-1000001_53176192_53176192/andrew-l-patterson-sr.

10 “History of the Prairie View Interscholastic League,” pvilca.org/history.html, accessed December 29, 2018.

11 Ibid.

12 Lester, 88

13 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994), 608-609.

14 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Play Statistics 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 214.

15 Rogosin, 172.

16 Lester, 88.

17 According to Lester, 448, Patterson tied for career East-West Game steals (4) with Henry Kimbro, Artie Wilson, and Sam Jethroe. Patterson required six games to reach the mark (compared with 10 games for Kimbro, and seven for Wilson and Jethroe).

18 Army Enlistment record, online: Ancestry.com.

19 Family memory; myheritage.com/person-1000001_53176192_53176192/andrew-l-patterson-sr.

20 James Overmyer, Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1993), 198.

21 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 164; Brent Kelly, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts from the Period 1924-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005), 347.

22 northdallasgazette.com/2014/09/11/former-nfl-player-looks-back-on-college-and-professional-career/ Accessed January 2015.

23 Ibid.

24 Family memory; myheritage.com/person-1000001_53176192_53176192/andrew-l-patterson-sr.

25 Yates Times (Jack Yates High School), September 7, 1984. Article part of digital archive supplied by Andrew Patterson (son) online at: myheritage.com/search-records?action=person&siteId=53176192&indId=1000001&origin=profile.

Full Name

Andrew Lawrence Patterson

Born

December 19, 1911 at East Chicago, IL (US)

Died

May 16, 1984 at Houston, TX (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.