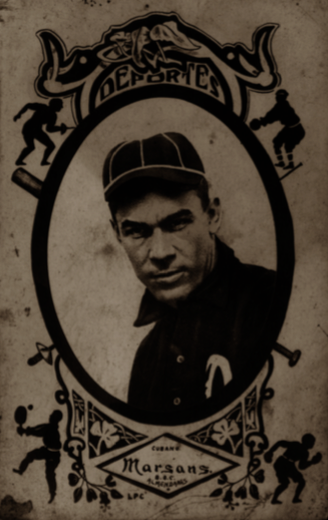

Armando Marsans

A brilliant defensive outfielder who briefly starred with the Cincinnati Reds, Armando Marsáns was the first Cuban player to make an impact in the major leagues. Dubbed “an aristocrat by birth, but a big-league outfielder by choice,”1 he was among baseball’s top stars before his career was derailed by an ill-fated attempt to challenge the reserve clause. Marsáns was known for his aggressive baserunning and was often praised for stretching singles into doubles and doubles into triples. “There is not a more intelligent player in the game than Marsans, who seems to have an uncanny knack of knowing what to do and when to do it,” wrote one reporter.2 He was also versatile. As a youngster in Cuba, Marsáns had learned to play all nine positions, and before he was through in the majors he played everywhere but pitcher and catcher.

A brilliant defensive outfielder who briefly starred with the Cincinnati Reds, Armando Marsáns was the first Cuban player to make an impact in the major leagues. Dubbed “an aristocrat by birth, but a big-league outfielder by choice,”1 he was among baseball’s top stars before his career was derailed by an ill-fated attempt to challenge the reserve clause. Marsáns was known for his aggressive baserunning and was often praised for stretching singles into doubles and doubles into triples. “There is not a more intelligent player in the game than Marsans, who seems to have an uncanny knack of knowing what to do and when to do it,” wrote one reporter.2 He was also versatile. As a youngster in Cuba, Marsáns had learned to play all nine positions, and before he was through in the majors he played everywhere but pitcher and catcher.

The son of a well-to-do Havana merchant, Marsáns reportedly participated in the Spanish-American War as a preteen, smuggling ammunition to Cuban freedom fighters who were fighting for independence from Spain.3 Marsáns came to the United States at age 11 in 1898, when, like many wealthy Cubans, his family moved to New York to escape the war.4 Marsáns picked up baseball, playing regularly in Central Park, and when his family returned to Cuba after a year and a half, he took his love of the game back with him. In 1905 he signed with Almendares, a powerful team in the professional Cuban Winter League. Marsáns and another promising youngster, Rafael Almeida, combined to lead the team to the pennant. In 1907 the team won another title, defeating a Fé team that included Negro League stars Rube Foster, Pete Hill, Charlie Grant, and Bill Monroe. In 1908 the Cincinnati Reds visited Cuba for a series of exhibition games against the best teams on the island. Marsáns’ Almendares club won four of its five games against the Reds, thanks mostly to pitcher José Méndez, but also with contributions from Marsáns, who scored the only run in a 1-0 victory on November 13.

By that time Marsáns and Almeida were both playing in the US minor leagues, having signed with New Britain of the Connecticut State League for the 1908 season. Though other teams in the league protested the Cubans’ presence on racial grounds, Marsáns was an outstanding player for New Britain, batting .285 over four seasons there, and on June 28, 1911, his and Almeida’s contracts were purchased by the Cincinnati Reds. The pair were purchased on the recommendation of Reds secretary Frank Bancroft, famed for his annual barnstorming trips to Cuba, who had been impressed by their play against the Reds in the 1908 exhibitions. At the time, the sale prices were reported as $2,500 for Marsáns and $3,500 for Almeida,5 although during Marsáns’ later legal battles with the Reds, owner Garry Herrmann would claim that he paid $6,000 for Marsáns alone.

Marsáns and Almeida were the first Cubans to reach the majors since 1873, and there were whispers around baseball that they had some “Negro” blood. The Reds rejected this at length, calling Marsáns and Almeida “two of the purest bars of Castilian soap ever floated to these shores,” and insisting that they were entirely of European descent. In Marsáns’ case, this was probably true; the surname Marsáns is of Catalán rather than Spanish origin. In the late nineteenth century about 8,000 people – Marsáns’ family likely among them – emigrated from Catalonia to Cuba. Racial mixing was fairly uncommon among the light-skinned catalanes, who ranked at the top of Cuba’s skin-color-based caste system.

Whatever their racial background, Marsáns and Almeida got along fine with their new teammates. “The gentlemanly deportment and fast work on the field of these boys have already made them popular with other members of the Reds,” the Cincinnati Enquirer reported on July 1, before the pair had even gotten into a game. Only about 15,000 Cubans lived in the United States in 1911, but the Reds acquired the Cuban players in part because, according to the Enquirer, they were “figuring on Marsáns and Almeida being good drawing cards in New York and Philadelphia, where there are thousands of Cubans.”6 Fans back in Cuba, meanwhile, were so enthusiastic that Marsáns and Almeida even had their own media escort. Victor Muñoz, sports editor of El Mundo in Havana, accompanied the Reds everywhere they went, much as the Japanese media would follow Hideo Nomo and Ichiro Suzuki nearly a century later.7

Finally on July 4, 1911, in the midst of one of the biggest heat waves ever to hit the Midwest, Marsáns and Almeida made their debuts against the Cubs at Chicago’s West Side Park. The heat was so sweltering that it caused 27 deaths in Chicago that day,8 and with the Cubs comfortably ahead in the first game of a doubleheader, Marsáns entered as a defensive replacement for exhausted right fielder Mike Mitchell. He went 1-for-2, and to the Enquirer’s Jack Ryder he “looked good at the bat and fast on his feet.”9 Marsáns spent the rest of the 1911 season as the Reds’ fourth outfielder.

Though there is no record of what their personal relationship was like, Marsáns and Almeida became inseparable in the public’s eye after spending nearly a decade as teammates with Almendares, New Britain, and Cincinnati. But Almeida failed to impress the Reds either at bat or in the field, and after three years on the bench was dispatched to the minors. Marsáns, meanwhile, became one of the brightest young stars in the National League, and one of the fastest. In 1912, his first full season, his .317 batting average and 35 stolen bases both ranked in the National League’s top 10. In 1913, despite various nagging injuries, he increased his stolen bases to 37 while batting .297, 35 points above the league average. He was adept at poking Texas Leaguers into the outfield, and was such a dead pull hitter that opposing teams employed exotic defensive shifts against him. Marsáns was known for his superior outfield defense and aggressive baserunning, and was often praised for stretching singles into doubles and doubles into triples. “There is not a more intelligent player in the game than Marsans, who seems to have an uncanny knack of knowing what to do and when to do it,” one reporter wrote.10

Marsáns made a strong impression on his first major-league manager, Clark Griffith, who left after the 1911 season to take over the Washington Senators. In the spring of 1912 Griffith offered the Reds $5,000 for Marsáns, but was refused.11 Griffith never did obtain Marsáns’ services, but he did develop an affinity for Cuban players unparalleled in baseball history. During Griffith’s 44 years in charge of the Washington club, 63 Cubans debuted in the majors – 35 of them with the Senators.

Marsáns was a genteel man who spoke and wrote excellent English, even going so far as to carry a dictionary in the hip pocket of his uniform pants. He was the very antithesis of what would later become the Latin American baseball stereotype, and was reported to have attended college in the United States, although this claim is probably false. Still, American sportswriters always emphasized that he was “of wealthy parentage and aristocratic stock.”12 In 1912 the Philadelphia Inquirer noted that Marsáns and Almeida “are both large land owners in Cuba and have independent incomes, and the fact that they continue to be ball players instead of prominent men of affairs on the island is simply because that is what they prefer to be.”13 Marsáns spent his offseasons managing a tobacco factory that he owned in Havana,14 and was well-liked enough by fans in Cincinnati to open a popular cigar store there. By 1914 his annual baseball salary, $2,100 when he joined the Reds, had more than doubled, to $4,400.15

Though almost universally well-liked,16 Marsáns was known for being headstrong and temperamental, which in 1914 led to the biggest scandal of his career. During spring training he got into a heated argument with his new manager, Buck Herzog, who accused Marsáns of lying about suffering an injury. Herzog suspended Marsáns, who then demanded to be traded, a request that was refused by Herrmann. Then on May 31, Herzog berated Marsáns for getting ejected from a game. “He is too sensitive,” Herzog said. “He should remember that baseball is a red-blooded game for rough and hardy men.” Herzog’s comments, according to one observer, were “not at all to the liking of the classy outfielder,”17 and Marsáns responded by jumping his three-year contract with Cincinnati. After being wined and dined by the owners of the St. Louis Terriers, he signed with their outlaw Federal League franchise. Marsáns was offered a three-year, $21,000 contract by the Feds,18 which he accepted after giving the Reds 10 days’ notice, the same notice a ballclub was required to give before terminating a contract with a player. Cincinnati immediately filed a lawsuit (in federal court because Marsáns was not a US citizen) claiming that its “property” had been jeopardized. After Marsáns had played only nine games with St. Louis, an injunction was issued barring him from playing in the Federal League pending the trial’s outcome. The Reds also retaliated by impounding the clothing and baseball equipment Marsáns had left in his locker in Cincinnati. Since Marsáns owned a cigar shop there, the club also tried to appeal to his business interests. “Marsans is very enthusiastic about his cigar business, and holds it close to his heart,” a correspondent wrote to Herrmann. “If he can be made to realize that his actions with the Cincinnati Baseball Club will not help the sale of his cigars, I am sure that he will act differently.”19

Marsáns’ case, along with that of Hal Chase, became a cause célèbre for supporters of the Federal League. Baseball Magazine dubbed it “the sensational Marsans case, one of the series of recent legal battles which have thrown the baseball world into an upheaval, and which threaten to wreck the entire game.”20 Unable to play while the two sides battled it out in court, Marsáns could do little but return to Havana, where he spent his days shark-fishing in the bay.21 “We are not restraining Marsáns and Chase from playing, but trying to get them to play,” Herrmann insisted. “It is the Federal League that is keeping them from playing, if any one is.”22 Bizarrely, Marsáns’ younger brother Francisco showed up in Cincinnati in September 1914, apologized to the Reds for any trouble Armando had caused them, and offered his own services to replace Armando in the outfield.23 Not surprisingly, the team declined. The Reds, who had been half a game out of first place when Marsáns jumped, finished the season dead last.

Because the National Commission had threatened to ban any player who competed against Marsáns, he was forced to play the 1914-15 Cuban Winter League season under the assumed name “Mendromedo.”24 In February 1915, with Marsáns still on the sidelines, his friend John McGraw visited him in Cuba, offering to trade for Marsáns if he would return to the National League with the Giants.25 But Marsáns would have none of it. He believed that the press, and New York writers in particular, treated him unfairly, saying they “always thought it funny to poke jokes at me.”26 Moreover, Marsáns said, the St. Louis owners “have treated me like a white man should be treated, and I am going to stick with the Feds.”27 Finally, on August 19, 1915, a federal judge in St. Louis set aside Herrmann’s injunction, ruling that Marsáns could play in the Federal League until the case was decided in appeals court. Marsáns returned to the Terriers the next day, and the team finished the season only percentage points out of first place.

But the legal battles had ruined Marsáns’ career. After the Federal League folded, his contract was assigned to the St. Louis Browns, but after being out of the majors for nearly two years, he was no longer the star he had been. Disappointed with his performance, the Browns traded him to the Yankees for Lee Magee on July 15, 1917. Baseball Magazine predicted that going to New York would revitalize Marsáns, as he was “a brilliant outfielder, once a .300 hitter and even now a most dangerous man on the bases.”28 But Marsáns had always been injury-prone, and soon after reporting to the Yankees he suffered a broken leg that ended his season. In 1918, at age 30, Marsáns gave it one more try with the Yankees, but batted only .236 in what turned out to be his final major-league season.

In 1923, after a four-year absence from American baseball, Marsáns returned to bat .319 in a brief minor-league stint with Louisville. Also in 1923, he briefly joined Martín Dihigo on the Cuban Stars of the Eastern Colored League, becoming one of the few men to play in both the major leagues and the formally organized Negro Leagues. In 1924, Marsáns’ last season in the United States, John McGraw got him a job as player-manager of the Elmira Colonels in the New York-Penn League, making him the first Latin American manager in minor-league history. He batted .280 in his farewell to American baseball. Marsáns played a few more winters in Cuba before retiring there, too, after the 1927-28 season.29

In all, Marsáns played on 10 pennant-winning teams in his 21 seasons in the Cuban Winter League, posting a lifetime average there of .261 in 455 games. He twice led the notorious pitchers’ circuit in runs scored, and in 1913 won the batting title with a .400 average. He also led the league in stolen bases three times but, playing most of his career in spacious Almendares Park, he hit only two lifetime home runs in 1,632 at-bats.30 Marsáns was also a longtime manager in the league, leading Orientales to the championship as player-manager in 1917. In the 1940s he managed Marianao, where his players included Ray Dandridge, future batting champion Roberto Ávila, and rookie outfielder Orestes Miñoso. He also managed Tampico in the Mexican League from 1945 to 1947, winning championships in 1945 and 1946.

On July 26, 1939, Marsáns became one of the first 10 men inducted into the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame. The inductees were honored with a bronze plaque placed at La Tropical stadium in Havana, where it still stands today. Little is known of Marsáns’ post-baseball life. His reaction to the Cuban Revolution of 1959 is unknown, but since the rebellion’s goal was to overthrow the wealthy aristocracy to which Marsáns belonged, it is hard to imagine him supporting the revolutionaries. Marsáns died in Havana a little over a year after Fidel Castro’s takeover, on September 3, 1960.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Washington Post, February 4, 1912.

2 The Sporting News, August 9, 1923.

3 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 28, 1912.

4 Robert Ripley, “Marsáns was Cuba’s first B.B. graduate,” unsourced news article, September 1912, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

5 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 28, 1912.

6 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 1, 1911.

7 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 8, 1911.

8 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 5, 1911.

9 Ibid.

10 The Sporting News, August 9, 1923.

11 “A Red Rebellion Makes Diversion,” unsourced news article, June 11, 1914, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

12 Philadelphia Inquirer, January 28, 1912.

13 Ibid.

14 Armando Marsáns, letter to Garry Herrmann, March 2, 1913, Garry Herrmann papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

15 Garry Herrmann papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

16 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 8, 1911.

17 Willis E. Johnson, “Marsans to Stick,” unsourced news clipping, January 16, 1915, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

18 Unsourced news article, June 8, 1914, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

19 Ben A. Hirschler, letter to Garry Herrmann, June 4, 1914, Garry Herrmann papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

20 Hugh C. Weir, “The Famous Marsans Case,” Baseball Magazine, September 1914: 54.

21 Undated news article, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

22 Sporting Life, July 11, 1914: 3.

23 Undated news article, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

24 Unsourced news article, November 25, 1914, Armando Marsáns clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

25 Telegram from John J. McGraw to Garry Herrmann, February 23, 1915, Garry Herrmann papers, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

26 Sporting Life, February 13, 1915: 9.

27 “Havana Training Trip of Terriers to Start Feb. 27,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 31, 1915: 1S.

28 Baseball Magazine, 1917, Vol. 19, Issue 5: 484.

29 Severo Nieto, Early U.S. Blackball Teams in Cuba (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

30 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003).

Full Name

Armando Marsans

Born

October 3, 1887 at Matanzas, Matanzas (Cuba)

Died

September 3, 1960 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.