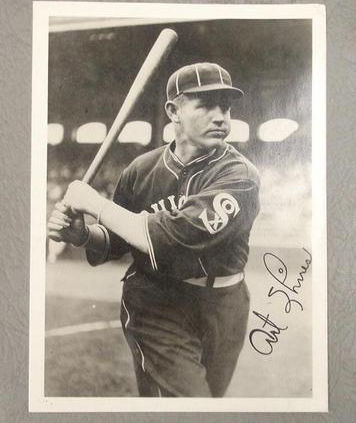

Art Shires

Art Shires arrived on the major league scene in 1928 with much fanfare, almost all of it of his own making. The Italy, Texas native nicknamed himself “Art The Great,” once boasted that, next to Babe Ruth, he was the biggest drawing card in the American League, and frequently stopped passersby on the sidewalk to ask them if they were going to that day’s ballgame to watch the outstanding first baseman, referring to himself, of course. The cocky first sacker also came with a ton of baggage and a hair-trigger temper that hampered his career and landed him in hot water on and off the field.

Art Shires arrived on the major league scene in 1928 with much fanfare, almost all of it of his own making. The Italy, Texas native nicknamed himself “Art The Great,” once boasted that, next to Babe Ruth, he was the biggest drawing card in the American League, and frequently stopped passersby on the sidewalk to ask them if they were going to that day’s ballgame to watch the outstanding first baseman, referring to himself, of course. The cocky first sacker also came with a ton of baggage and a hair-trigger temper that hampered his career and landed him in hot water on and off the field.

Alcoholism, insubordination, and a serious knee injury limited his time in the Major Leagues to only four years, but had he taken the game more seriously, he most likely would have had a more successful career. He batted .291 over those four seasons, hitting .349, .312, and .302 in his first three seasons before his injury-plagued 1932 season effectively ended his stint in the majors. Shires also dabbled in boxing, going 5-2 with five knockouts during his brief career, and wrestling; ran for a seat on the Texas House of Representatives; and was twice accused of killing a man, including his long-time friend, Hi Erwin, a former minor league player and umpire.

Charles Arthur Shires was born on August 13, 1907 in Italy, Texas to Josh and Sallie Shires. He was the third of nine children, six boys and three girls, and was two years older than his brother Leonard, who also went on to play professional ball, spending nine seasons in the minor leagues before retiring from the game in 1936. As a teenager, Shires played for the Waxahachie High School baseball team with future major leaguers Paul Richards and Jimmy Adair, and then attempted to catch on with the Washington Senators in 1925, trying out as a pitcher and going by the name of Robert Lowe in order to maintain his college eligibility. The Nats passed. Instead he began his career in 1926 with Waco of the Texas League, and the 18-year-old was impressive, hitting .280 and fielding at a .991 clip. He was even better in 1927, batting .305 with a .410 slugging percentage, then enjoyed his finest season to date in 1928, batting .317, slugging .478, and committing only five errors in 105 games.

He so impressed the Chicago White Sox that they purchased his contract, along with those of Johnny Watwood and George Blackerby, on July 31, 1928. It didn’t take long for Shires to show the Pale Hose how audacious he could be; only two days after the sale was announced, Shires balked at the purchase price, insisting that Waco had received a better offer from the Cleveland Indians, which would have brought him a “liberal cut.” In protest, Shires joined a semi-pro team called the Baytown Oilers. It was merely the beginning of a long list of problems Shires would bring to the teams that employed him.

Shires eventually relented and joined the White Sox in mid-August. On August 20, the Chicago Tribune announced that Shires, “the first basing sensation of the minors,” would make his debut against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Fenway Park. “Bud Clancy has played every inning of every game and will start on a rest if Shires seems all he’s cracked up to be,” wrote the Trib. Shires began his major league career with a bang, rapping out four hits against Hall of Famer Red Ruffing, including a triple in his first at-bat, described by sportswriter Edward Burns as a “mighty swat that went to the farthest point of center field.” He rapped out three more hits and helped the White Sox defeat Boston by a score of 6-4. So cocky was the 21-year-old that he boasted after the game, “So this is the great American League I’ve heard so much about? I’ll hit .400!”

He ended up batting “only” .341 in his short rookie season and so impressed White Sox brass that he was named team captain. For a franchise still reeling from the Black Sox scandal—the Sox had only two winning seasons since and finished no higher than fifth place in their eight previous campaigns—it was a curious decision, akin to giving Hal Chase the responsibility of stamping out gambling, or putting Babe Ruth in charge of curfew. It didn’t take long for Shires to prove that he had as much business being the captain of a baseball team as Ty Cobb had of being Pope.

In what Shires would later call his “ego racket,” he drew immediate attention to himself. Two days after the first sacker’s debut, sportswriter Frank Young named Shires a “keen contender for the crown as the tobacco chewing champion,” which was held by Tigers catcher Pinky Hargrave. “Now there is considerable doubt as to leadership,” wrote Young, “the cud which Shires masters being heavy enough to make him lean slightly toward the left side.” Umpire Tommy Connolly took the hyperbole a step further and called Shires, “the chewingest player I’ve seen in forty years of baseball.”

Shires also had a taste for fine clothing and reportedly owned dozens of suits, hats, spats, tuxedos, and attire for golfing, horse riding, and yachting. John Kieran wrote about Shires, “He wore his fancy suitings and he sported his glittering canes. His haberdashery was chosen with infinite taste, rich but not gaudy. In the evenings he ventured forth in correct evening dress, braving the taunts and insults of his team-mates who had no proper appreciation of the finer things in life.” Westbrook Pegler called Shires “a sartorial sunburst.” (Legend has it that when Shires was traded to the Washington Senators in 1930, he reported to the clubhouse wearing a green jacket with pearl buttons, white trousers with green stripes, and a Roman candle necktie. He immediately accosted Al Schacht and said, “I understand you’re a pretty well-dressed fellow. Well, when you see me, hide.” Schacht didn’t take kindly to the insult and, when asked by a reporter if Shires was the best dressed player on the team, Schacht replied, “No, he’s the most dressed”).

But Shires’ natty attire couldn’t contain the demons within, and he soon found himself in trouble, first with the law, then with the White Sox. On December 28, 1928 a 53-year-old Shreveport, Louisiana man named Walter Lawson died from an injury he suffered to his spinal chord at the base of his brain. The man’s death, though unfortunate, probably wouldn’t have garnered much national attention, except that his injuries came when Shires angrily threw a baseball at a group of disapproving fans during a game between Waco and Shreveport on May 30. The ball hit Lawson in the head and he died seven months later. The fact that Lawson was a “Negro” made the incident even more controversial (although one can only imagine the public’s “outrage” in 1928 had the roles been reversed).

Lawson’s wife, Ida, sued Shires for $25,411, but only a day after the lawsuit was reported in the papers, Shires was exonerated by a grand jury on March 29, 1929. The suit was dropped from the court’s docket after an agreed judgment for $500 on January 11, 1930.

That was not the last of his troubles, however. Though he was considered one of baseball’s future stars—one reporter called him “a talented guardian of the front door…destined to lead in the first basing art before the conclusion of another year”—his off-the-field antics were becoming a problem. A day after being cleared by the grand jury in Lawson’s death, Shires arrived at the team’s spring training hotel long after curfew and so drunk that he walked right past White Sox manager Lena Blackburne without recognizing him, went out into the courtyard and began howling at the moon. Blackburne immediately stripped Shires of his captaincy and warned that further infractions would result in a long suspension without pay and a $100 fine.

White Sox owner Charles Comiskey ordered Shires back to his home in Italy, Texas until he was in playing condition, and the Washington Post dubbed him, “the freshest busher in baseball.” Shires charged Blackburne with being “incompetent and tyrannical” and the Post partially sided with Shires, placing much of the blame on Comiskey, who had gone through six different managers since the Black Sox scandal. “It may be that the White Sox have gotten the idea that a manager of their team is never more than a straw boss,” wrote the Post.

“Straw boss” or not, Blackburne vowed to “weed out the bad element” on the team; Shires, Ted Blankenship, Sarge Connally, Bill Hunnefield, and Bill Barrett were expected to be playing elsewhere in 1929. Pegler reminded his readers that Comiskey was “mulish, old, crotchety, and ill” and warned that the White Sox owner had the power, as did all baseball magnates, to blacklist players, dooming them to a “state of suspended business animation, bound to a job, but forbidden to work at it.”

The recalcitrant first baseman remained on the roster, but was planted firmly on the bench while Bud Clancy played first base and played it well. Shires was used as a pinch hitter a handful of times and made it known to everyone that he wasn’t happy about his new role and that he hadn’t been given a fair chance to show his worth as a ballplayer. Finally on May 15, everything came to a head. The White Sox got off to a .500 start, winning six and losing six by the end of April, but they went into a funk and lost eight of their first nine games in May, putting them at 7-14 on May 11. They won three of their next four, however, and sat in a sixth-place tie with the Senators on May 15, 5 ½ games out of first place.

Prior to that day’s game against the Red Sox at Comiskey Park, Shires was admonished by Blackburne for wearing a red felt hat during batting practice; Blackburne felt Shires was trying to “burlesque the game” and wasn’t taking his job seriously. Shires countered with a “number of large words not suited to household purposes” and threatened to run Blackburne out of his job. Blackburne suspended Shires on the spot and fined him $100. Shires left the park, but returned before the end of the game to confront the White Sox manager. Words were exchanged before the two men came to blows, each landing a punch to the other’s face before they were separated.

The next day Blackburne declared that he was through with Shires and it was up to Comiskey to decide what to do with the first baseman. The Chicago Tribune felt the best option would be to trade him for a heavy hitter. Shires insisted he was through with baseball and planned to go back to school to get his law degree.

Neither happened. Shires apologized and was reinstated less than two weeks after his fight with Blackburne. He finally made it into the starting lineup on June 4 and went 2-for-4 with a double and a run scored, but the White Sox lost to the Yankees, 4-2, dropping their record to 16-30. They were only at the quarter mark of the season but were already 17 ½ games behind the first-place Athletics. Although there was still plenty of time for Chicago to make up ground, their already slim chance of copping the pennant was now non-existent and they’d be lucky to finish north of seventh place.

The team’s dismal record didn’t temper Shires’ lofty opinion of himself, however. During a radio interview later that month, he told listeners, “No use of a great hitter like me getting a flock of skimpy singles. You never get your name in the headlines with singles. It’s distance the public wants. From now on I’m aiming for the next county. I’m going out for home runs. Come on out and razz me; you’ll go away cheering me when I slam them against the bleachers. I sure can hit that ball and I’m not so bad around first base either.”

He was right on both counts. Shires hit .312 and led the team with a .370 on-base percentage, and set career highs in doubles with 20, triples with seven, and home runs with three, and slugged a career-best .433. He also fielded at a career-best .991 clip. Unfortunately he couldn’t keep his temper in check and was suspended again in mid-September after getting into another fight with Blackburne in a Philadelphia hotel room. Blackburne was passing by Shires’ room and heard a commotion, and when he peeked into the room, he found Shires using empty liquor bottles as “indian clubs and shouting for more liquor.” Blackburne accused Shires of being drunk (again); Shires responded by knocking Blackburne down and bouncing his head off the floor repeatedly. Shires not only gave Blackburne a pretty good beating, but he turned his ire towards White Sox Traveling Secretary Lou Barbour as well when Barbour tried to intervene. According to reports, Shires almost bit off Barbour’s right index finger during the fracas (other reports claimed that it was Blackburne who accidentally bit Barbour, and one report had Barbour accidentally biting himself). Police took Shires into custody, but incredibly Blackburne and Barbour refused to press charges.

As far as Blackburne was concerned, however, Shires was persona non grata. “Shires is out, gone, through, busted forever. And I’m not kidding. He’ll never get back into organized baseball after this.” Shires countered by explaining that he was tired of being spied on by Blackburne and Barbour, who would wire reports of the players’ activities to Comiskey. “They have cooperated to wreck what might have been a fair ball club, and I’m glad to have had the opportunity to thrash the pair of them together when they came gumshoeing into my room tonight.” Later on he was more succinct: “Barbour and Blackburne walked into my room with their chests sticking out. Can you imagine those two stool pigeons trying to scare me? I just started swinging.”

Shires was suspended for the rest of the season, then did what only Art Shires had the audacity to do; he held out for more money, demanding $25,000 while insisting that he was as big a “drawing card” as anyone in the American League with the exception of Babe Ruth.

It was a ridiculous claim for someone who wasn’t even assured a roster spot after spending a good portion of the 1929 season under suspension for routinely pummeling his manager, both physically and verbally. In fact, Comiskey hadn’t even reinstated him to the team yet, and he was so taken aback by Shires’ demands that he began calling him “Art the Peculiar” and the “Peculiar One.” The Old Roman countered with an offer of $7,000, insisting Shires was lucky to be getting even that much.

“As a major league ball player Shires didn’t show he was anything out of the ordinary last year,” said Comiskey. “He will have to be a little better than the ordinary player now to overcome his peculiarities. And you must remember the White Sox are trying to employ ball players and are not in the market for any wild men from Borneo.”

Shires eventually agreed to terms and signed for $7,500, far less than he was demanding, but slightly more than Comiskey wanted to pay. Though Shires may have been nothing out of the ordinary, he was still one of the better hitters on the team and, despite all his bluster to the contrary, Comiskey appeared to be willing to overlook Shires’ petulance to get his bat in the lineup.

But Comiskey was courting disaster by keeping Shires in a White Sox uniform. In the winter of 1929, Shires, buoyed by his pugilistic victories over the much smaller Blackburne, decided to try his hand at boxing. He enjoyed brief success, knocking out “Dangerous Dan” Daly in 21 seconds in front of the biggest fight crowd in the history of White City amusement park in Chicago (Daly was actually Jim Gerry, also identified as Jim Gary, a friend of Blackburne’s from Columbus, Ohio), which earned him a fight against George Trafton, a professional football player who played center for the Chicago Bears. Meanwhile, Shires demanded a bout with Cubs center fielder Hack Wilson, who had gained a reputation of his own for decisively settling arguments with his fists.

While Wilson was mulling over Shires’ challenge, Trafton beat the “Great One” to a pulp and knocked him down three times in a fight that lasted only five rounds because neither man had the strength to continue (Trafton later said, “I couldn’t get my hands up. They weighed 100 pounds apiece.”) The fight was dubbed by one sportswriter as the “Laugh of the Century,” while another scribe called it the “Battle of the Clowns.” Trafton’s teammate, Bill Fleckenstein, was so offended by sportscaster Pat Flanagan’s description of the debacle that he punched him in the nose. Soon after, Wilson decided against fighting Shires because the White Sox first sacker had already been beaten and Wilson had nothing to gain by fighting a man with a tainted record.

Undaunted, Shires applied for a New York boxing license. But not long into his “career,” he was suspended by the Michigan Boxing Commission after it was learned that his next scheduled opponent, “Battling” Criss, was offered money to “take a dive.” Only two days later, Gerry admitted that he, too, took a dive after being threatened that he’d be “taken for a ride” if he refused (Shires was alleged to have been suspended in Illinois and New York as well, and one report had him suspended in as many as 32 states).

The boxing commission eventually cleared Shires after failing to find any evidence that he or anyone associated with him fixed his fights. But before Shires could step back into the ring, Commissioner Landis kayoed Shires’ boxing career by issuing an ultimatum, “quit the prize ring or quit baseball.” In fact, he issued an edict that impacted all baseball players who considered following in Shires’ footsteps: “Hereafter any person connected with any club in this organization who engages in professional boxing will be regarded by this office as having permanently retired from baseball. The two activities do not mix.”

That Comiskey would retain a player accused of fixing fights underscores how desperate he was to restore his team to its former glory. But he finally tired of Shires’ act and sent him to Washington for southpaw Garland Braxton and catcher Bennie Tate on June 16, 1930. Shires was batting only .258 with little power, and had reached base at a .298 clip, and the White Sox’s catching situation was in such a shambles that the team would eventually use seven different men behind the plate that season.

Shires responded well to the trade and even tried a more humble approach with his new team, although he failed miserably. “You’re a made man now,” he told Senators skipper Walter Johnson, “and I don’t want this club to stand in awe of me. Just call me Shires.” He then explained that his troubles were over because Washington “appreciated his [alcohol] problem.”

“Gin is not good for an athlete,” Shires explained. “Walter Johnson told me so. Did Lena Blackburne tell me so when I was with the White Sox? No. He just told me I couldn’t drink it. He didn’t appeal to my reason.”

Shires was terrific for the Senators, batting .369 and slugging a career-best .464 in 38 games, but despite a 94-60 record, Washington finished in second place, eight games behind Connie Mack’s powerful Athletics. The Senators had three very good first basemen in Shires, 16-year veteran Joe Judge, and Joe Kuhel, whom the Senators purchased from Kansas City for $65,000. Judge was coming off one of his best seasons but would turn 37 early in the 1931 season; Shires had just turned 23 and Kuhel was only 24. Even if Judge stuck around for a couple more seasons, it looked like the first base job would eventually be inherited by either Shires or Kuhel.

But reports surfaced that Shires detested sitting on the bench behind Judge and “lost interest” in his work when he wasn’t starting. There were also rumors that Shires had violated team training rules during the season and wasn’t keeping himself in shape. Johnson was willing to overlook those things to keep Shires’ bat in the lineup and tried Shires out in the outfield, but according to reports, he “failed to impress” in that capacity. His days in Washington were numbered.

The offseason between 1930 and 1931 proved to be extremely busy for Shires and he appeared to love every minute of it. He was named to a major league All-Star team that played a series of games against the Negro League’s Chicago American Giants in October 1930, and though the team included future Hall of Famers Harry Heilmann and Charlie Gehringer, the Chicago Tribune gave Art “Whataman” Shires top billing. The Giants took three of four games from the All-Stars; Shires went 5-for-6 in Saturday’s game, then he and Walter “Steel Arm” Davis “kept the stands in an uproar by their clowning” in Sunday’s 6-1 affair, won by Giants hurler Willie Foster.

Shires joined a second All-Star team, featuring A’s stars Lefty Grove and Bing Miller, and headed to Los Angeles to play a series of exhibition games at Wrigley Field. He was also slated to appear in films that winter and had agreed to get married on camera when a studio producer offered him $1,000 for the right to film the ceremony. But when the money failed to arrive, Shires married his bride, 18-year-old University of Wisconsin co-ed Elizabeth “Betty” Greenabaum, at the county courthouse instead. “Now, I’ve got a wife, and I’ll need more money. Guess I’ll have to be a hold-out next spring,” Shires joked with reporters after the ceremony. “This is just batting practice,” Shires continued. “There will have to be a church wedding later, although I’d rather face that great pitcher ‘Lefty’ Groves [sic] than do this over again.”

Shires got married on November 10 and his comments about possibly holding out for more money appeared in newspapers the next morning. A little more than two weeks later, the Senators sold the first baseman to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association for $10,000. His comments probably had little to do with his sale to Milwaukee; in fact, he most likely sealed his own fate during the 1930 season when he told Senators owner Clark Griffith that he was “too good a ballplayer to be sitting around on a major league bench.” Griffith apparently agreed and placed him on waivers. When every other major league team passed up on the opportunity to claim him, Griffith sent Shires to Milwaukee.

“Shires is the best ballplayer I have ever sent back to the minors,” Griffith told reporters after the deal was struck, “and I must confess that, in asking waivers, I simply wanted to find out what clubs were interested in Art so that I might work up a trade of some kind. As none wanted him, I decided to accept the bid of the Milwaukee club.”

Sportswriter Frank Young blamed the demotion on Shires’ “bad boy” reputation and thought the humbling experience would teach Shires a lesson. “The knowledge that big league clubs do not want ‘bad boys’ on their roster may do him a lot of good, however, and this, together with the fact that he has just taken unto himself a wife, may bring him the sense of responsibility which appears to be all that he needs to make him a success as a diamonder.”

Surprisingly, Shires was thrilled with the move, calling it “one of the greatest breaks I ever got.” “I won’t be any trouble to anybody. I just want to play baseball and earn my way back to the big show. I’ll give the town a pennant winner sure.” Before he was to join the Brewers, though, Shires had plenty to keep him busy—in late November he was signed by Universal Studios to play opposite Kane Richmond in episodes nine and ten of “The Leather Pushers.” While he was in Hollywood, the brash first baseman decided to take on the city’s finest. Clearly intoxicated and cocky as ever, he waltzed into a police station and challenged the officers to throw him out of the building. Instead they tossed him in jail for drunkenness, then tacked on a concealed weapons charge when they found a set of brass knuckles in his pocket.

After his release, he took time to write a letter to Johnson, in which he called his former skipper, “the best manager and greatest fellow I ever played for.” He admitted that he didn’t behave as he should have while sitting on the Senators’ bench, and that he was going to take Johnson’s advice and “hustle my way back to the big show.”

Shires caused a stir with his new team when he failed to show up for spring training in 1931 as scheduled, but it turned out his departure from Chicago was delayed by a snowstorm and he arrived only a few days late. He promptly displayed the antics for which he was famous by refusing to shave until the Brewers won their first exhibition game. When they finally defeated Little Rock on March 23, Shires shaved, an event that was covered by the Chicago Tribune. Clearly it was a slow news day in the Windy City.

Shires got off to a hot start with Milwaukee and was batting .443 at the end of May. By mid-July major league teams began to show interest in him again—the Boston Braves, Cleveland Indians, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Philadelphia Phillies reportedly inquired about his services, prompting Brewers president Louis Nahin to announce that Shires would be going to the highest bidder at the end of the American Association’s season. When the Chicago Cubs showed interest as well, it was reported that the Brewers were demanding $100,000, but were hoping to get $75,000. The Cubs were reportedly ready to offer Milwaukee $50,000 and were just waiting for a scouting report to arrive before pulling the trigger.

But the next few weeks came and went and Shires was still a Brewer. The Cubs announced on August 3 that the Brewers’ new asking price of $35,000 and two players was too steep and that they’d “virtually given up the idea” of acquiring Shires. Another two weeks went by and Shires decided to stump for himself, but not in his typical way. “We all learn. I decided to bear down and play ball. That’s what I’ve been doing and the record speaks for itself. The sport writers wanted color and I was it. But I don’t blame them—they’re all fine boys. But my ambition now is to be the best first baseman in baseball.” In fact, Shires had been so well-behaved during the ‘31 season, that writers began referring to him as “Art The Silent.”

Another month came and went and, rumors to the contrary, Shires was still a minor leaguer. Not only that, but Milwaukee’s price had dropped considerably. On August 30, it was reported that the Philadelphia A’s had purchased Shires for $20,000 and two players, but both Connie Mack and L.C. McEvoy, president of the St. Louis Browns, who were affiliated with the Brewers, denied a deal had been struck. That didn’t stop writers from speculating about a move to Philadelphia—one report had A’s first baseman Jimmie Foxx moving to third base to accommodate Shires. But any deal involving Shires was quashed when the A’s purchased St. Paul’s star first baseman Oscar Roettger on September 10.

Roettger was having a fine season, hitting .357 and slugging .516 with 38 doubles, seven triples, and 15 homers. But Shires’ campaign was better—he led the American Association in batting with a .385 average, hits with 240, and total bases with 334, and slugged .536 with 45 doubles, eight triples, and 11 homers. At the end of September when no major league team claimed him, Shires expressed disappointment that he might have to spend another season in the minors in 1932, and seemed to recognize that his drinking and past transgressions made him undesirable to most big league clubs.

“I admit that I lifted a stein or two on occasion,” he told reporters, “but I was always out there the next day to play or produce. I thought I was entitled to another shot in the big show, and I was disappointed when no one put in a bid for me…If I’m not drafted, and I don’t expect to be, I’ll come back here [Milwaukee] and play just as hard as I did this year. I’ll show ‘em. I’m young, only 24, and I’ll be back up [in the majors] yet.”

Shires received a reprieve on October 9 when the Boston Braves acquired him from Milwaukee for $10,000 and catcher Al Bool, who batted only .188 for the Braves in 1931 and boasted a career average of .237 in parts of three seasons. It was a far cry from the $100,000 and two players the Brewers had originally asked for. He wasn’t with the Braves long before announcing he’d been signed to a one-year deal worth $11,000, and that he was bent on becoming the “best first baseman in the senior circuit.” But it looked like Shires was up to his old tricks. Braves owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, refuted the signing, insisting that none of the team’s contracts had even been mailed out yet. Sportswriter Shirley Povich found this particularly amusing and wrote, “In signing a contract before he received one, Shires must have performed a miracle. Perhaps he’s psychic. Figuratively, he stole first base.”

A week later, Albert Keane, sports editor of the Hartford Courant, reported that a deal was in the works that would send Shires to the New York Giants for first baseman Bill Terry, who was in the midst of a contract holdout. But Terry eventually signed and remained with the Giants (had that deal happened, it would have been a horrible trade for the Giants; Terry enjoyed his best season in 1932 and played four more seasons, batting .340 from 1932-1936 with three 200-hit seasons.)

As if his tenure with the Braves hadn’t started off on an odd enough foot, things got even weirder when it was announced that not only would Shires be teammates with Al Spohrer, but that the Braves backstop would be Shires’ roommate. It was an interesting combination considering Shires scored a TKO against Spohrer in the boxing ring in front of more than 18,000 spectators on January 10, 1930. After the fight, Shires shouted at the Boston Garden crowd, “I didn’t want Al Spohrer, I wanted ‘Hack’ Wilson!” Eight days later, Commissioner Landis issued his “baseball or boxing” edict. Now two years later, the wannabe pugilists were expected to share the same living quarters. In fact, the two had been friends all along. Shires agreed to fight Spohrer because the latter was in desperate need of money and could benefit from the purse. After the fight, Shires sent Spohrer’s ill wife a bushel of flowers, and the friendship between the ballplayers blossomed.

Heading into the 1932 season, it appeared the 24-year-old Shires had finally started to mature. Four days before the Braves were scheduled to open the 1932 season in Brooklyn, the Washington Post wrote, “Art (Whataman) Shires appeared to be quite subdued while with the Braves here yesterday. He seemed to have his mind on the game rather than on verbally impressing the cash customers with his greatness…The veteran, Rabbit Maranville, seems to be the cut-up on the team, while catcher Pinky Hargrave yesterday chewed a much larger cud of tobacco than did Art.”

Both Shires and Spohrer contributed greatly to Boston’s 8-3 victory over the Dodgers on Opening Day, going a combined 5-for-8 with three runs scored. In fact, Shires helped the Braves jump out to a 5-2 record in their first seven games by going 10-for-27 (.370) with five RBIs and four runs in the season’s first “week.” But things took a turn for the worse on April 22 when Shires suffered two injuries, the second of which knocked him out of action for almost a month. In the first inning of a game against Brooklyn, Dodgers outfielder Johnny Frederick smashed a grounder that took a wicked hop and hit Shires in the face, knocking him out and breaking his nose. Shires, no doubt used to taking shots to the face, stayed in the game. But in the ninth, he was knocked down for the count and wouldn’t return until May 15. Joe Stripp laid down a bunt towards third baseman Fritz Knothe, who made a strong throw that beat the runner. But Shires was in Stripp’s path and the two men collided head-on. Stripp was down for three or four minutes, but Shires had to be carried off the field and into the clubhouse. X-Rays later revealed a torn ligament in his left knee.

Shires returned to the lineup on May 15 in an 8-3 win over the Cardinals, but he wasn’t the same hitter who’d started strong in April. Regardless, Braves manager Bill McKechnie was happy to have his first baseman back, and in early June told reporters that the other players “missed his inspiration and the team missed his playing.” But as June unfolded into July and July into August, McKechnie soured on Shires, who’d batted only .228 since his knee injury, and benched him in favor of Randy Moore. McKechnie accused Shires of the same things the Senators accused him of—”failure to keep in condition, and a lack of esprit de corps and whole-hearted diligence.”

McKechnie then tried to trade Shires to Chattanooga of the Southern Association, but Shires blocked the deal by producing a doctor’s note that claimed he was out of condition, so McKechnie gave him his unconditional release. When Judge Fuchs learned of the release, he ordered it rescinded, and advised Shires to retire instead, offering to pay him his full salary while covering all medical expenses required to repair his knee. Shires accepted the offer and underwent surgery on his knee on August 25.

With no job, a depleted bank account, and a bum knee, things began to look bleak for Shires. It would have been easy to feel sorry for him. In a candid interview with John Kieran, he revealed some information that made him out to be a somewhat sympathetic figure. “Listen, I kidded others but I never kidded myself,” he told Kieran. “I’m not the smartest fellow in the world but I know a few things in a small way. Sure, I lost my job in the American league. Shucks, that’s only an incident in my career. I went to Hollywood once and made two movie shorts and got $7,500 for it. Took $500 of it and spent it and put $7,000 in the bank. The next day the bank shut up and never has opened since. From vaudeville, baseball, and fighting in the ring and one thing and another, I had $30,000 in cash at one time. Lost every nickel of it in a real estate venture…I had just $85 in the world left.” But Shires seemed to take it all in stride. “Times are tough but it’s a pretty good world at that. I have no regrets and no complaints. I’ll just do the best I can and let it go at that.”

And despite his brief stay in the National League, Shires made a positive impression on many of the circuit’s umpires. “There isn’t a National League umpire who wouldn’t go through hell and high water for Art Shires,” agreed N.L. umps, “Dolly” Stark, George Barr, and “Ziggy” Sears. They recounted how Shires would threaten to punch a teammate in the nose if he got out of hand with the umpires, and once stood up for arbiter George Magerkurth during an argument with Braves shortstop Rabbit Maranville. “Magerkurth, still on trial as a big league umpire then, has regarded Shires as a prince ever since that day, and Magerkurth’s sentiment is one shared by all of us,” concluded Barr.

In private, however, things were very different. Shires began to physically abuse his wife Betty, punching and slapping her in November. Not surprisingly, Art announced only two months later, in January 1933, that he and Betty had separated. He cited his frequent traveling for the rift and insisted that he and his wife were still friends. Curiously, Betty refused to comment. But the world according to Shires was often volatile and muddled; two days later he announced that he and Betty had reconciled and the separation was off.

Only a week before, Commissioner Landis had reinstated Shires from the voluntarily retired list. And on the same day that Shires announced he and his wife were back together, McKechnie announced that Shires would be given a second chance with the Braves, but that he’d have to beat out Baxter “Buck” Jordan for the first base job. Shires had his work cut out for him—the 25-year-old Jordan tore up the International League, batting .357 and slugging .576, then hit .321 and slugged .434 for the Braves. No one on the Braves hit better, and only Red Worthington and Wally Berger posted higher slugging percentages than the rookie first sacker.

But Shires proved worthy of the challenge, at least early on, and impressed Shirley Povich enough in mid-March 1933 for Povich to aver that Shires was “making himself extremely useful once more.” But when Judge Fuchs offered Shires a reduced salary to serve as Jordan’s backup in early April, Shires refused and left the team to see if he could catch on with a strong minor league or semi-pro club. With almost anyone else, that might have been the end of the story, but with Shires, it was just the beginning. A week later he appeared in Braves camp wearing a Braves uniform and working out at first base in place of a mysteriously absent Jordan. It was speculated that Jordan hadn’t been living up to his promise, but McKechnie insisted that Jordan was just ill and would be fine. Any questions about Shires’ role with the team were answered three days later when he was sold to Toronto of the International League.

In true form, Shires balked at the move, announced that he would “never play minor league ball again,” and began mulling over an offer of $25,000 a year to return to boxing. He appeared to be serious about the switch and even told German heavyweight Max Schmelling that he’d be ready to fight him within a few months. Shires received a brief reprieve when Fuchs canceled the deal with Toronto and sold him to the St. Louis Cardinals instead. But Cardinals manager Gabby Street made it clear from the beginning that Shires was unwanted. “I’m sure Shires is not coming to the Cardinals. We don’t need him. We have two first basemen now. He’s probably to be sent to some other club.”

Sure enough, a week later the Cards sent Shires and three others to Columbus of the American Association for second baseman Burgess Whitehead. This time Shires accepted the deal, although he insisted the Cardinals had erred just as the Senators had. “The major leagues will realize once again, just as they did two years ago, that they made a mistake in waiving the great Shires out of the big show. I am a major league ballplayer and I’ll prove it before I hang up my glove at the end of the season.”

Shires did well for Columbus, hitting .313 and slugging .477 in 44 games, but again, he couldn’t keep himself out of trouble. On May 23 he was ordered by Judge Joseph Cordes to pay his former attorney, William Timlin, the $119.33 he owed him for defending Shires in a breach of contract suit. Two days later, Shires was involved in a fight with a 32-year-old Louisville, Kentucky man named Jack Deacon, who broke his leg and suffered numerous lacerations when Shires picked him up and threw him down a staircase. Shires was defending Louisville Colonels second baseman and former high school teammate Jimmy Adair, who started the fracas when he accused a woman of trying to “roll” him for $125. Deacon took exception to Adair’s accusations; Shires stood up for Adair because he was a “small guy,” and pitched Deacon down the stairs.

Shires and Adair were charged with malicious assault and sued for $50,000. Deacon was charged with the same crime, as well as “conducting a disorderly house.” Two others were charged with malicious assault, and one was charged with disorderly conduct. Deacon’s attorney argued that his injuries were so severe that his leg may have to be amputated and that he could possibly die. The hospital where Deacon was laid up during the hearing claimed Deacon was in no immediate danger of either. Charges were eventually dismissed against everyone when Deacon decided not to pursue prosecution, but Shires was allegedly forced to pay Deacon’s hospital bills.

Shires found himself in the news again on June 15 when American Association president Thomas J. Hickey barred Shires and three other members of the Columbus club from playing for the Red Birds for the rest of the season on the basis that they were being paid more than the maximum allowed by the league. Columbus exceeded the monthly payroll of $6,500 agreed upon by members of the Association and was fined $500. They also lost three of their best hitters and one of their better pitchers. Charlie Wilson was hitting .356 and slugging .575, Gordon Slade was hitting .353 and slugging .540, Shires was hitting .313 and slugging .477, and Jim Lindsey was 7-2 with a 3.69 ERA.

The Red Birds sat in first place with a 2 1/2 game lead over Indianapolis at the time of the decision. The decree had no effect on them, however, as they went on to finish 15 1/2 games ahead of the field en route to a pennant. In the wake of the Association’s decision, Columbus traded Shires, Wilson, Lindsey, and pitcher Sheriff Blake to Rochester of the International League. Slade was recalled to the Cardinals.

Shires’ troubles were far from over, though. On August 14, he was charged with signing a false affidavit in connection with his 1933 contract and fined $200. Slade was also fined $200, while Wilson and Lindsey were assessed $100 penalties. Apparently the Cardinals had agreed to “remunerations in excess of that designated in their contracts.” The three men appealed the decision and won; the fines assessed against them were ordered remitted.

The move to Rochester proved to be somewhat fortuitous as they also qualified for a pennant before losing to Buffalo in the playoffs. Shires batted .277 but slugged only .390 for the Red Wings, and was eventually replaced by future Hall of Famer Johnny Mize. He wouldn’t stay in Rochester long. On November 16, 1933, Shires was dealt to Toledo for Bill Weeney. He wouldn’t stay in Toledo long, either—he was sold to Fort Worth of the Texas League prior to the 1934 season. Not only was he no closer to rejoining the major leagues, but he was getting further away—Fort Worth wasn’t affiliated with a major league team in 1934.

Shires spent a full season with Fort Worth and batted .287 with an anemic .377 slugging percentage. He also made 17 errors at first base, after committing only three in 1933. With his baseball career flagging, Shires decided it was time to step back into the boxing ring. “I figure I’m the Texas heavyweight champ now, but I guess I’ll have to go through the formality of winning it.” In reality, Shires was in desperate need of money and looking for ways to obtain it. He was matched up against Sid Hunter on January 31, 1935 and was knocked out in the second round when Hunter caught him with a hard right cross to the chin.

Less than two weeks later, Shires fought a palooka named Joe Daley and knocked him out in the third round. It would prove to be Shires’ final professional fight and he finished his career with a 5-2 record and five knockouts. Then the absurd happened—he was hired to manage the Harrisburg Senators of the New York-Pennsylvania League at a salary of $3,500. He also played a little first base and batted a career-low .243, although he was nifty in the field, committing only four errors in 59 games. That was his last and only stint as a manager.

Shires was rumored to have been offered the job of piloting the Springfield, Illinois team in the Three-I league in 1936, but the league shut down that year and didn’t reform until 1937. Instead, he made his living refereeing wrestling matches and playing semi-pro baseball. When asked if he had considered playing ball at the professional level, he admitted that he could no longer afford to live on a minor league baseball salary. “This salary limit in the minor leagues makes it hard for a fellow to get along,” he explained. “I’ve got a family to support and I’m afraid I can’t afford to play baseball in the minors.” But he did express interest in landing a job in the Pacific Coast League, not so much for his own career, but because he wanted to get his young son, three-year-old Charles Jr., a job in the movies.

In the meantime, Shires played semi-pro ball in Chicago for the Mills team, which also featured former major leaguers Hippo Vaughn, Bert Atkinson, and Charlie Uhlir. Shires played mostly in the outfield and batted over .600 but, according to Frank Finch of the Los Angeles Times, the Mills team released “Art The Great” because they didn’t like that he was playing ball during the day and singing in cabarets at night. Shires then joined Bob Fothergill’s Detroit semi-pro team.

In September 1936, some troubling news was made public when Shires’ wife Betty filed for divorce and charged that Art had struck her again. She cited “cruelty” as her reason for seeking the divorce. She and Shires had been separated for more than a year. The divorce was finalized on November 23. From there, Shires’ life deteriorated even further—he made money refereeing wrestling matches, then became a wrestler himself in 1937, but he was virtually broke. When he was ordered to pay $5 a week to support his three-year-old son, he argued his own case. “When a man’s slipping, people want to step on him,” he lamented. “I’m trying to find work now, but, because of my knee, I can’t play through a full season. For five nights I’ve slept in a chair, unable to pay for a hotel room.”

Though Shires was in the news on a regular basis, newspapers were printing “whatever happened to Art Shires?” stories on an equally regular basis. He signed with the Springfield Empires, another Chicago-area semi-pro team, and played with Hall of Fame pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, who was 50 at the time, and former Reds and White Sox outfielder Evar Swanson. After the season, he was doing business in Los Angeles when he found himself in trouble again, crashing his car into a telephone pole and suffering a dislocated vertebra.

In May 1938, Shires was recruited to play softball for a team of boxers, including Henry Armstrong, against a team of wrestlers that included “Man Mountain” Dean. Shires belted three home runs in the fighters’ 15-14 victory over the grapplers. He continued playing softball, but began to fade from view as sportswriters stopped their “whatever happened to…” queries.

Before his light dimmed completely, though, an article appeared in the Hartford Courant, linking Shires to Chicago gangster Al Capone, the most notorious mobster in American history. The article in question detailed a fairly innocuous incident in which Shires was photographed shaking Capone’s hand at Comiskey Park before a White Sox game. When American League president Will Harridge saw the photo he was apoplectic and warned that players caught fraternizing with fans before a ballgame would be fined.

But further investigation shows that the incident may not have been banal after all. When Commissioner Landis forbade Shires (and others) from boxing while he was still a major leaguer, it wasn’t just because “boxing and baseball don’t mix,” it was also because Landis was aware of rumors that Capone and his men had a hand in the Shires-Trafton bout. It’s not a stretch to believe Capone’s thugs also fixed the fight against Jim Gerry and offered “Battling” Criss money to take a dive against Shires. At the time of Landis’ decree, the Black Sox scandal was still less than a decade old; the last thing major league baseball needed was a fresh scandal involving fixed fights and gangsters.

After the July 1938 article about Capone, Shires received little press. In 1941, reporter Harold Ratliff of the Dallas Morning News interviewed scouts Bessie and Roy Largent, who expressed sorrow for Shires. Bessie, the only female major league scout in the country, was especially heartbroken. “What a pity,” she said. “After all these years we can’t help but shed tears when we think of Art and the great opportunity the [White] Sox lost in not having someone who knew how to handle him. He would have been a million-dollar drawing card and a great player but success went to his head.”

Shires was mentioned sporadically in brief snippets of wrestling news, then more or less disappeared from the papers until May 18, 1948 when the Chicago Tribune reported that Shires, who’d operated a shrimp house and bar in Dallas since 1943, was running for a seat in the Texas House of Representatives. “I’m going to fight the battle of the little man,” the 41-year-old Shires told reporters. “The little man really gets pushed around in Texas.” He was confident that he’d get the support he’d need for a victory, “Labor’s going to be for me and so will all the people in sports. And the sports writers all ought to back me,” he joked, “I’ve furnished them enough copy.” Apparently no one backed him; he was defeated and went back to his restaurant.

He didn’t stay out of the news long, though. On December 8, 1948 newspapers across the country greeted readers with disturbing news:

SHIRES CHARGED WITH MURDER OF HI ERWIN, EX-BALL PLAYER

Dallas, Tex., Dec. 7 (AP).—Art Shires, former major league first baseman, was charged with murder today in the death of W.H. (Hi) Erwin, 56, former professional baseball player.

Erwin died in a hospital here Saturday. Officers quoted Shires as saying he had a fight with Erwin October 3. Shires was questioned last night and released on a $5000 bond in a habeas corpus writ.

Shires and Erwin had been friends for 25 years. Erwin had played for Dallas of the Texas League and umpired in the American and Western Associations. According to Shires he went to Erwin’s cleaning and pressing shop to give him a steak, but things went horribly wrong. “He hit me across the face with a telephone receiver and I knocked him down without thinking,” Shires told detectives. “I had to rough him up a good deal because he grabbed a knife and started whittling on my legs.” According to the charges, Shires “willfully and with malice forethought killed William Hiram Erwin by beating him with his fists…and stomping him with his…feet.”

Erwin’s physician reported that the victim died of internal injuries suffered in a fight. That’s when police got involved. But Dr. P.A. Rogers, who treated Erwin after the fight, reported that Erwin died from hypostatic pneumonia and cirrhosis of the liver “with contributing causes being blows to the head, chest and abdomen.” A hearing revealed that Dr. E.E. Muirhead, who supervised Erwin’s autopsy and conducted microscopic examination of the deceased’s tissue, agreed with Rogers that Erwin died of cirrhosis of the liver and pneumonia. Both testimonies would eventually work in Shires’ favor.

W.L. Sterrett referred a murder charge against Shires to the Dallas County grand jury on December 16. Though the grand jury found that Shires “did inflict serious bodily injuries” to Erwin, the charge of murder was reduced to aggravated assault on January 31, 1949. A little more than a year later on February 11, 1950, Shires was charged with simple assault and fined $25. He had been involved in the deaths of two men in 20 years and got off with slaps on the wrist both times.

Curiously, six years later, the White Sox invited Shires to participate in an Old Timers’ game at Yankee Stadium in August 1956; apparently they felt he could still pull a crowd, even in New York. The White Sox’s roster boasted some fine ballplayers like Red Faber, Ed Walsh, Ray Schalk, Muddy Ruel, Jimmie Dykes, Johnny Mostil, and Bibb Falk. The Yankees loaded up with some all-time greats—Joe DiMaggio, Lefty Gomez, Bill Dickey, Home Run Baker—and All-Stars like Charlie Keller, Tommy Henrich, and Allie Reynolds, and won the game, 4-1. Shires spent some time in right field, but failed to record an official at-bat.

As the Washington Post put it once upon a time, Shires returned to “obscurity as a sports figure” and wasn’t heard from again until July 13, 1967 when he died from lung cancer at his home in Italy, Texas. He was 60 years old.

Author’s Note

Shires’ birth date is alternately listed as both August 13, 1906 and August 13, 1907 by multiple sources, and therefore the age at which he died was alternately reported as both 59 and 60 by multiple sources. The Ellis County, Texas census record of January 30, 1920 lists his age as 13, making the 1906 birth date most likely.

Sources

Heritage Quest, 1920 Census/Texas/Ellis County/Justice Precinct No. 8. Supervisor’s District No. 329; Enumeration District No. 154.

Chicago Defender, 1928

Chicago Tribune, 1928-1956

Dallas Morning News, 1936-1967

Hartford Courant, 1933-1948

Los Angeles Times, 1928-1950

New Orleans Times-Picayune, 1929

New York Times, 1933-1935

Springfield Sunday Union And Republican, 1934

Washington Post, 1928-1935

www.retrosheet.org

www.baseball-reference.com

Full Name

Charles Arthur Shires

Born

August 13, 1906 at Italy, TX (USA)

Died

July 13, 1967 at Italy, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.