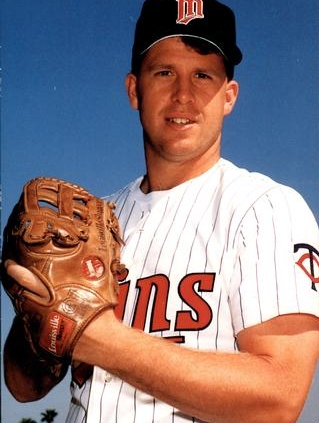

Mike Trombley

At first blush, it might appear that a kid growing up in the western Massachusetts area known as the Pioneer Valley wouldn’t be playing baseball in a hotbed of the national pastime. But for those who excel at an early age and persist, there are rewards to be reaped, and this was exactly the case for Mike Trombley, who spent 11 years in the major leagues, most of them in a Minnesota Twins uniform through much of the 1990s.

At first blush, it might appear that a kid growing up in the western Massachusetts area known as the Pioneer Valley wouldn’t be playing baseball in a hotbed of the national pastime. But for those who excel at an early age and persist, there are rewards to be reaped, and this was exactly the case for Mike Trombley, who spent 11 years in the major leagues, most of them in a Minnesota Twins uniform through much of the 1990s.

Born on April 14, 1967, in Springfield, Massachusetts, Michael Scott Trombley grew up in nearby Wilbraham as the son of a financial adviser. His talent was evident at an early age: While at Wilbraham Junior High School, he won New England honors in a pitch-hit-and-run competition held at Fenway Park, and at Minnechaug Regional High School where he played baseball and football to help the school maintain its high standard of athletic prowess in the mid-1980s. He was a jack-of-all-trades on the diamond but played catcher most frequently; taking the mound was a rarity for the right-hander, and this development only took root as he was reaching the collegiate level. Yet, serving as a backstop was crucial to Trombley’s obtaining a better overall understanding of the game and helped him make the transition from catcher to pitcher.

After graduating from Minnechaug, he moved on to Deerfield Academy in the fall of 1985 to prepare for his matriculation at Dartmouth, where his goal was to play both sports for the Big Green. Although he enjoyed his time playing football at Deerfield, the excitement of the gridiron there did not match what he experienced at Minnechaug, so the importance of football diminished greatly in his eyes. But a curious twist of fate unexpectedly pointed him in the southerly direction of Duke University rather than north to New Hampshire.

Already accepted by Dartmouth, Trombley had a meeting with his adviser at Deerfield, who suggested that playing baseball in the more comfortable climes of the Southeastern United States might be more attractive than the chill of Northern New England. “Better weather — that’s where I went,” was the adviser’s brief sales pitch, and Trombley, now curious about the possibility of a more attractive option, agreed to let him contact Duke baseball coach Larry Smith.

Informed that Trombley was now interested in casting his lot with the Blue Devils, Smith also learned that Trombley had just struck out 19 batters in game against Northfield Mount Hermon, so his most recent credentials were very impressive. After being checked out by a Duke coach and a subsequent visitation to the campus in Durham, Trombley was indeed headed to Duke. The change of collegiate destination provided an uncomfortable moment for Trombley when he had to impart the bad news to Dartmouth coach Jim Walsh, who had treated him with utmost respect during the recruiting process. Years later Trombley remained stung by how guilty he felt at reneging on his commitment to the Big Green.

Trombley found that his time at Duke was an overall worthy venture, yet he admitted to no small degree of buyer’s remorse. He found that he would be pitching against powerful Atlantic Coast Conference schools that frequently hung losses on the Blue Devils, who had far less success on the baseball field than they had on the basketball court. Trombley’s personal exploits emerged from the wreckage of a team that was simply no match against North Carolina, NC State, Georgia Tech, Clemson, and other formidable opponents. One rare thrill of victory came when Duke ended a dreadful 19-game losing streak in 1988, and he recalled that even with a personal total of three meager wins that year, he was one of the team leaders in victories. Trombley also spent that summer with the Falmouth Commodores of the Cape Cod Baseball League.

Returning for his junior season at Duke, he was given the honor of being named the Blue Devils’ captain, and Baseball America, perhaps sensing that Trombley would be taken in the following year’s amateur draft, wryly noted that he “has only one more season of punishment to endure before he is drafted.”1 Another milestone for the pitcher was in progress, as it was during this time that he met Barbara Pecht; the couple would be married in 1992, and over the next several years they welcomed two daughters and a son to their family.

Exiting Duke with statistics of a pitcher who could have been associated with the 1962 New York Mets — by the end of his junior year he had compiled an uninspiring career mark of 6-22 with an ERA of 5.11 — Trombley had nevertheless pitched well enough that he considered himself “a good pitcher on not such a great team” rather than “a big fish in a little pond.” His third year was telling in one respect and was likely the reason he attracted the attention of the Minnesota Twins: He was far and away the leader of the Blue Devils staff, a proven workhorse who claimed, “[M]y arm has never hurt me a day of my life” and was tops with 15 starts, five complete games, and 89 strikeouts in 91 innings pitched.

Selected in the 14th round of the June 1989 amateur draft, Trombley joked years later that he “signed my name before we knew what the offer was” because he was “so happy that someone wanted me.” But upon reporting to Kenosha of the Class A Midwest League, he immediately began to post numbers that belied those that might have been expected of a lower-round draft pick. By now he was filling out as a strapping 6-foot-2, 200-pound hurler possessed of a determined sense of focus.

After winning five of six decisions and fashioning a 3.12 ERA, Trombley was sent to another Class A affiliate, Visalia in the California League, where he went 2-2 while sporting an even tidier ERA of 2.14. Although Trombley admitted that he had little leverage as a newer member of the organization and a low-round draft pick, he declined the Twins’ request over the next two seasons to play in the instructional league and winter ball because he had committed himself to fulfilling a promise to his parents — completing his bachelor of arts studies in psychology and economics at Duke, which he accomplished in the fall of 1990. That year was also pivotal in his early professional career: he again pitched for Visalia and was 14-6 with a 3.43 ERA in 25 starts and two relief appearances. Trombley confessed that he was lucky to be part of a quality team that also featured future big leaguers Pat Mahomes, Rich Garces, and Denny Neagle, who taught him how to throw a changeup.

“The Twins had a tremendous minor-league system with great coaches,” Trombley said years later, because as a small-market club they had to compete against teams who had the benefit of better financial resources. “They really invested in their own [players]. … They put a lot of value in their minor-league system.” Scott Ullger and Ron Gardenhire still draw praise from Trombley as does his minor-league pitching coach Rick Anderson, who “really took me under his wing … [because] I was kind of the same type of pitcher that he was. When you were on the mound, you knew he was pulling for you. He really helped me.” Trombley also credited coach Rick Stelmaszek with providing guidance and a steady hand once he later reached the major leagues.

Trombley’s future continued to brighten when he earned a promotion to Orlando of the Double-A Southern League in 1991. As a full-time starter, he won 12 and lost seven, and his ERA was 2.54 over 191 innings in his 27 assignments. He hurled seven complete games, and led the league with 175 strikeouts while allowing only 153 hits and issuing 57 walks. This certainly was a perfect time for him to be forging heady statistics with a franchise whose major-league club had just won an exciting World Series.2

Guided by a mature mindset that allowed him to accept whatever role the Twins wished to place him in, Trombley demonstrated a respectful work ethic that curried favor with all levels of management. In the minors he didn’t see starting as significantly more important than relieving; rather, he placed more value on the number of innings pitched — period — because, in his mind, more IPs meant that the coaches had an increased opportunity to see how capably a pitcher could perform. In fact, while Trombley acknowledged that there was more exposure and better money for top-rank starters, he relished a set-up role because he anticipated going to the ballpark each day knowing that there was a good chance that he might be called to duty.

Although Trombley was an aspiring candidate to make the jump to Minnesota in the spring of 1992, he was hampered by an ankle injury in early training camp and was eventually sent to Portland of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. He reprised his starting role (10-8, 3.65, 138 strikeouts over 165 innings) and was called up to the Twins in mid-August when Paul Abbott was placed on the disabled list with a shoulder problem. Trombley debuted on the 19th with an inning of relief against the Indians in Cleveland, and over the remaining weeks of the season, in which the defending World Series champions finished six games out and in second place of the American League West, he started seven games, had two more stints out of the bullpen, and ended with a record of 3-2 and a solid ERA of 3.30 in 46⅓ innings.

Initially Trombley had a cool relationship with Twins manager Tom Kelly because, as the pitcher later confessed, some wisdom the skipper tried to impart did not register at the time. “It’s almost like your father yelling at you when you’re young. Then the older you get, you realize, ‘That’s what he’s getting at.’ He was looking out for me,” Trombley came to understand. Kelly tried to foster a spirit of camaraderie among the entire team because “he was a big ‘us’ guy, we’re all in this together.”

Trombley’s curveball was rated major-league quality, and his trial in Minnesota led him to believe that he would join the club’s rotation entering 1993. But because fellow pitcher Willie Banks was out of options, the former first-round pick was slotted as the fifth starter, thereby relegating a disappointed Trombley to the bullpen. He did manage to start 10 games in his 44 appearances, but his statistics were indicating better performances when he pitched in relief. As his desultory season played out between starting and relieving, he ended with a record of 6-6, an ERA of 4.88 in 114⅓ innings, and he surrendered an alarming 131 hits, including 15 home runs. His performance seemed to reflect the straits the Twins had fallen into: Two years removed from postseason glory, they were moribund in fifth place with a dismal 71-91 record.

Now at a crossroads going into the 1994 season, the Twins were in a newly created division, the American League Central, but their performance was not significantly different from a year earlier. For Trombley’s part, he was again hoping to land the fifth starter’s spot, but his fate was sealed after he allowed 24 earned runs in 25 innings in the club’s spring-training rotation. Again shunted to the bullpen of a team in danger of falling into also-ran status, Trombley was bombed in his first appearance of the season and never seemed to get untracked. Even though he was credited with two wins in April, he was finally sent to Salt Lake of the PCL in mid-May to work out his problems, and over the next two months he won half of eight decisions but logged a 5.49 ERA in 60⅔ innings.

After his recall to Minnesota in July, he pitched unimpressively and ultimately ended the year with a worrisome 6.33 ERA. Not only was he at risk of being bypassed by several other prospects coming through the farm system, but the whole season came crashing to an end when all major-league players went on strike on August 12, never to return until 1995. In more ways than one, it was a forgettable season.

By the time the Major League Baseball Players Association and the club owners came to terms to resolve the strike, all parties seemed to be in catch-up mode during the spring of 1995. For Mike Trombley, his crossroad season of 1994 only proved to be a harbinger of more travails to come. He began 1995 at Salt Lake, where he pitched decently: five wins, three losses, a 3.62 ERA, and, importantly, he allowed only three home runs among the 71 hits he yielded over 69⅔ innings. Seeming to have righted his listing ship, Trombley was recalled in June and used as a starter for nearly all of his 20 appearances. But his earned-run average never wavered far from 6.00, and after ending with a 4-8 record and a 5.62 ERA, he was outrighted in December. Both he and the Twins, who went 56-88 and finished an abysmal 44 games out of first place, had resoundingly bottomed out.

While the likelihood of a turnaround by the team did not seem in the offing, Trombley’s invitation to 1996 spring training as a nonroster invitee was perhaps a reflection of how desperate Minnesota was for pitching — any pitching. Confronted by the reality of a string of subpar seasons that rendered his “top-prospect” label a distant memory, Trombley developed a forkball under the tutelage of veteran Rick Aguilera, and the results were revealing. After starting the opening two months at Salt Lake — where, as a closer, he compiled a 2-2 record with a 2.45 ERA and 10 saves — a rejuvenated Trombley seemed to have at last found a role. For the remainder of 1996, he won five of six decisions for Minnesota, sported a nifty 3.01 ERA, and saved a modest total of six games, second on the team to Dave Stevens’s 11.

For Trombley, there was a financial benefit to this enlightenment in the form of a two-year contract for $775,000 that Twins general manager Terry Ryan offered as part of an effort to retain players he deemed essential to keeping the team’s nucleus intact. There would be no further trips to the Minnesota minor-league Triple-A affiliate, but neither was Trombley completely out of the wilderness. Instead of being tabbed a closer, he found himself used often in later innings as a set-up man in 1997 and 1998. Ironically, the pitcher for whom he was doing the set-up work was none other than Aguilera, Trombley’s forkball mentor.

Only once in that two-year stretch would Trombley take the mound in a starting role, as his duties were primarily in set-up situations. His cumulative statistics for 1997 and 1998 were 8-8, two saves, and a 3.97 ERA in 179 innings pitched. Come 1999, the set-up duties seemed to be his stock-in-trade, but when Aguilera was traded to the Chicago Cubs on May 21, the deal opened yet a new door for Trombley. As The Sporting News described the realignment of the Twins bullpen, “Now Trombley will be asked to fill the void [created by the trade of Aguilera]. Trombley has the composure — he has been an excellent setup man, and setup men often pitch in more difficult situations than closers. He’s a calm person well-liked by his teammates, and he has three good pitches.” But the publication also cautioned that although “Trombley describe[s] himself as ‘happy as a guy can be being a setup man,’… he remains untested under pressure” as the primary closer.3

Trombley adapted very well, saving nine games in June, four in July, six in August, and two more in September. His overall line of a 2-8 record and 4.33 ERA may not have turned heads, his total of 24 saves did. Admittedly, the supposed pressure experienced by a team that had long fallen out of contention was drastically different from that faced by a club in the heat of a pennant race, but Trombley, as always, took his job seriously and proved his value not only to the Twins but to other teams who would be in the market for a quality late-inning pitcher when the season concluded. This particular season was also Trombley’s free-agent season.

“I was lucky enough to get a lot of offers,” he recalled years later, but at the time he was confident that he could parlay his impressive 1999 season into a three-year deal. And as the Twins front office was plotting its personnel strategy for the near future, “the first item on [GM Terry] Ryan’s agenda is the Trombley equation.”4 Shortly after the season ended, Minnesota offered a $5.2 million contract for the expected three years, but the Baltimore Orioles upped the ante with a lure of $7 million, which Trombley claimed to be a record given to a set-up man at that time.5 “I never wanted to leave the Twins,” he said in a 2008 interview. “I don’t consider myself a greedy guy, but it was an opportunity for me to make a considerable amount more in Baltimore.”6

Trombley signed with the Orioles on November 18, 1999, and there was a confluence of several factors that worked in his favor: The Orioles offered better money, he was interested in pitching on the East Coast for a team closer to his home in Fort Myers, Florida, and although he was expected to slip into the set-up position behind Baltimore closer Mike Timlin, Trombley was also potential insurance for Timlin, who led the AL with nine blown saves in that year.

The Orioles began the 2000 season well but quickly dropped to fourth place in May. Team pitching was failing in all aspects, and by mid-May only three hurlers had ERAs under 5.00. Trombley was among the culprits, surrendering home runs at a frightful pace (nine in 24 innings), and as the club foundered in fourth place through August, save opportunities were few and far between. Timlin was traded at the end of July, but rather than use Trombley in his place, the Orioles entrusted those duties to a promising rookie, Ryan Kohlmeier, who emerged from the farm system as the new closer for the last two months of the year.

The 2001 season saw Trombley back in his familiar set-up role, but when Kohlmeier struggled, the versatile veteran regained the chance to serve as the closer. Yet, as the Orioles became ensconced in fourth place and Kohlmeier proved a flash-in-the-pan, Trombley (3-4, 3.46 ERA, six saves) persevered and drew the attention of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Looking to fill a demand for pitching, the contending Dodgers traded Kris Foster and Geronimo Gil to the Orioles on July 31 in exchange for Trombley. While Baltimore struggled in the standings and looked to trim its payroll, Los Angeles had just climbed to the top of the NL West and needed help both in holding its slim divisional lead and giving a break to fellow set-up reliever Matt Herges. But the Dodgers’ new acquisition was charged with four losses while posting an unproductive 6.56 ERA, and the club limped to the end of the season in third place. Trombley ended his two-team stint with a 3-8 record with an overall 4.38 ERA.

Disappointed to have left the Eastern city where he had hoped to finish his career, Trombley’s brief tour with the Dodgers provided a denouement of sorts for the right-hander. The concluding month of his time in Los Angeles was filled “with tons of distractions”: He regretted not pitching well for the Dodgers, the terrorist attacks of September 11 caused a huge degree of shock for the entire nation, and his third child was to be born days after the tragedy. On a flight home to be with his wife on the 16th, he departed Los Angeles on a plane carrying many passengers who had lost loved ones — or were presumed to have been lost — and he quickly found that being in the company of so many grieving people to be especially traumatic. “And the whole ride home, people were crying. I mean, six hours. … It was torture, it was just torture. And I’m thinking to myself, ‘I’m going home to see my baby being born. I’m playing baseball.’ And I’ll never forget flying back to LA after my daughter was born, and I’m thinking, ‘What am I doing? What’s important here?’ It was like the switch went off … and I lost my edge,” he said later, referring to his struggle to reconcile the reality of current events while trying to continue playing baseball.

Trombley would like to have played two more years, but when his competitive fire was nearly extinguished during that fateful month, he realized that a segue to a new life away from baseball was close at hand. He attended 2002 spring training in Vero Beach but pitched poorly, and though he suspected that the Dodgers might have been trying to trade him, he drew his release on April 8, which Trombley ironically found to provide a measure of relief from the pressure of struggling to remain in the game. There was a slight expression of interest in him by the Florida Marlins courtesy of Trombley’s connection with new manager Jeff Torborg, but instead he landed in Minnesota when the Twins picked him up one week later.

After a one-game refresher stint with Fort Myers of the Florida State League and nine appearances with Edmonton of the PCL, he was back with the Twins in mid-May, but the script changed little. In five outings totaling four innings, Trombley pitched to a 15.75 ERA, the nadir coming on May 17 at Yankee Stadium when he was trusted with a three-run lead going into the bottom of the 14th inning but served up a grand slam to Jason Giambi in what turned into a woeful 13-12 loss. Amazingly, the Twins wanted only to send him back to Edmonton, but Trombley instead requested his release, which the Twins granted on June 3. Thereafter he kept himself in good physical condition, yet even the desire to work out casually with other ballplayers ultimately abandoned him, and at the age of 35 he finally stepped away from the game for good.

His career record over 11 major-league seasons was 37 wins, 47 losses, 44 saves, an ERA of 4.48, and over the course of 795⅔ innings he allowed 800 hits, issued 319 walks, and struck out 672 batters. The versatility he displayed in roles as a starter, set-up man, and closer, especially in his years in Minnesota, were emblematic of manager Tom Kelly’s philosophy in doing whatever was needed to help the team.

As the balance of his baseball contract furnished a bit of short-term income, Trombley noted that “being home was not a bad thing,” since he was now able to spend time with his wife and three children. He gave back to the community by coaching youth sports while his kids were involved in those activities.

Soon moving into a new career centered on finance and real estate businesses, he and his family relocated to his hometown of Wilbraham, Massachusetts, where Mike and Barbara eventually assumed ownership of the financial services company founded in 1965 by his father. “I knew I was going to be a financial guy,” Trombley said, recalling a time when he assumed he would spend his immediate post-college days in the financial field, not on a baseball field. But he didn’t mind the interruption, saying, “It was a great life.”

Last revised: September 9, 2020

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Mike Trombley for granting the interview from which this work’s quotations were derived, unless otherwise indicated. Additional information also provided by Kim Handzel of Trombley Associates.

This biography was reviewed by James Forr and Len Levin and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

Mike Trombley, interview with author, June 11, 2020.

Baseball America

baseball-reference.com

duke_ftp.sidearmsports.com

The Sporting News

Springfield (Massachusetts) Union

twinstrivia.com

Notes

1 Baseball America clipping, Mike Trombley scrapbook.

2 The Twins won the 1991 World Series over the Atlanta Braves in seven games. They won the deciding Game Seven on a walk-off hit by Gene Larkin in the 10th inning.

3 Jim Souhan, “Minnesota Twins Notes,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1999.

4 Jim Souhan, “Minnesota Twins Notes,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1999.

5 The Sporting News; Nov. 29, 1999: 73.

6 Trombley quoted in “Mike Trombley interview,” https://twinstrivia.com/interview-archives/mike-trombley-interview/. Viewed June 27, 2020.

Full Name

Michael Scott Trombley

Born

April 14, 1967 at Springfield, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.