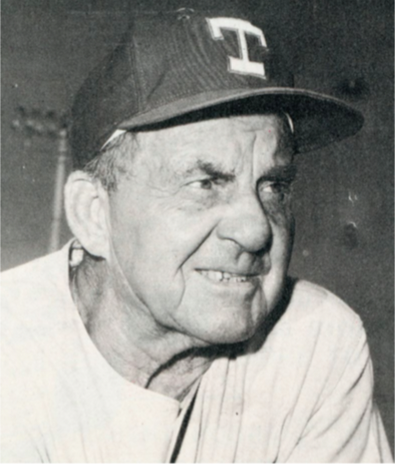

George Susce

In 1955 Cleveland News sportswriter Ed McAuley noted that “[George] Susce is a man of many admirable qualities, but the ability to hit a baseball frequently was not among his assets.”1 At the time this was offered, Susce was 11 years removed from his last major-league appearance and well along into a coaching career that extended into the 1970s. Remembered with the rather incongruous moniker of “Good Kid” – a reputation seemingly earned only after he retired – Susce (pronounced SUE-see) reportedly engaged in over 37 fights – losing 36 of them – during the first six years of his career. Despite the terrible won-lost record, he continued throwing fists, often at his own teammates. (This was possibly due to another nickname ascribed to him by his mates: “Sweet Susie.”) This combative behavior eventually hampered his career, something Susce readily acknowledged years later when he said, “I guess I was too aggressive in those days.”2

In 1955 Cleveland News sportswriter Ed McAuley noted that “[George] Susce is a man of many admirable qualities, but the ability to hit a baseball frequently was not among his assets.”1 At the time this was offered, Susce was 11 years removed from his last major-league appearance and well along into a coaching career that extended into the 1970s. Remembered with the rather incongruous moniker of “Good Kid” – a reputation seemingly earned only after he retired – Susce (pronounced SUE-see) reportedly engaged in over 37 fights – losing 36 of them – during the first six years of his career. Despite the terrible won-lost record, he continued throwing fists, often at his own teammates. (This was possibly due to another nickname ascribed to him by his mates: “Sweet Susie.”) This combative behavior eventually hampered his career, something Susce readily acknowledged years later when he said, “I guess I was too aggressive in those days.”2

George Cyril Methodius Susce was born in Pittsburgh on August 13, 1907, the youngest of two sons of Paul and Mary V. (Yager) Susce. His Slavic ancestry helps to explain his middle names – the ninth-century brothers Cyril and Methodius were the patron saints of the Slavs. Susce’s parents were born in Austria-Hungary in the second half of the nineteenth century and emigrated from the crumbling empire to the United States in 1902. (They married that same year.) Paul went to work in Pittsburgh’s thriving steel mills, where he labored for more than 40 years. The family lived three miles east of the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers, and one mile south of Forbes Field, home of the Pittsburgh Pirates. The ballpark opened two years after George was born and he passed it every day on his way to Schenley High School in Pittsburgh’s North Oakland neighborhood. The industrious child owned a year-round morning and evening newspaper route and, during the baseball season, was a batboy for a semipro team while hawking peanuts and soft drinks at Forbes Field.

Susce was a gridiron star in prep school3 and went on to play one season at St. Bonaventure University in Allegheny, New York. Playing on offense and defense as a fullback and defensive back, he received honorable mention as an All American.4 But football paled in comparison to his true passion, baseball. Blessed with a strong arm, Susce spurned attempts by the Schenley Spartan coaches to move him from his preferred catching spot to the mound. His exploits on the high-school diamonds attracted major-league scouts – most notably St. Louis Cardinals executive Branch Rickey – but Susce chose college instead. (His ambition was to become a dentist.) But in early 1929, after just one year at St. Bonaventure, he had a change of heart. Discovered on the semipro sandlots in Pittsburgh, Susce was invited to a tryout with the Philadelphia Phillies, where he quickly caught the attention of manager Burt Shotton. Having sold the contract of reserve catcher Johnny Schulte in January, the Phillies were in need of a replacement. Susce was signed by Joe O’Rourke and immediately assigned to the parent club. It took little time for Susce to engage in his first altercation. During an at-bat against Philadelphia Athletics righty Eddie Rommel in a Florida exhibition, the youngster charged the mound when he thought the veteran hurler was intentionally throwing at him. Innings later the A’s mild-tempered outfielder Bing Miller tried to choke Susce after a hard collision at the plate.

On April 23, 1929, Susce made his major-league debut, against the New York Giants in the Polo Grounds, as an extra-inning defensive replacement for starting catcher Walt Lerian. He got his first plate appearance the next day, striking out as a pinch-hitter against future Hall of Fame lefty Carl Hubbell. Susce played in just 15 more games the rest of the season. Except for a June 25 starting assignment against the Boston Braves in the nightcap of a doubleheader at Braves Field – a game in which Susce connected for his first major-league home run, a solo shot against Braves lefty Bunny Hearn – he was used solely as a defensive replacement or pinch-hitter. A .294 average in limited play may have warranted additional play, but his belligerent disposition, which Philadelphia fans took to be colorful, was less welcome among his teammates. During the offseason – presumably after the Phillies acquired catcher Harry McCurdy – Susce was assigned to the Buffalo Bisons in the International League.

It is unclear how much playing time, if any, Susce got in Buffalo. The 1930 Bisons used as many as five catchers with the lion’s share of play devoted to future AL backstop Frank Grube. Midway into the season Susce was returned to the Phillies, who released him on July 30. Immediately signed by the Giants, Susce was assigned to the Kansas City Blues in the American Association.5 The 22-year-old demonstrated an aptitude at the plate – .304 in 125 at-bats – but drew considerable criticism behind it, both in his handling of pitchers and with his strong but inaccurate arm. The next year Susce reported to the Blues spring training as, at best, the club’s number-three catcher. In June he was demoted to the Springfield (Illinois) Senators in the Three-I League, where he handled the bulk of the catching responsibilities for the Class-B club. During the offseason he was obtained by the Beaumont Exporters, the Detroit Tigers affiliate in the Class-A Texas League.

That same offseason saw the departure of catchers Johnny Grabowski and Wally Schang from the Tigers roster around the time the club was also engaged in negotiations that would have sent a third backstop, Ray Hayworth, to the Washington Senators. Though Hayworth remained with the club, eventually wrestling the starting job from 36-year-old Muddy Ruel, the unsettled and ever-changing developments prompted the club to break its 1932 spring camp with Susce as insurance. He made two late-inning defensive appearances through May 13 before being assigned to the Montreal Royals in the International League. There he shared the catching responsibilities with Grabowski and veteran backstop Lee Head through the remainder of the season.

In 1933 Susce narrowly missed an opportunity to make the parent club before the Tigers opted for minor-league catching prospect Frank Reiber instead. Demoted to Beaumont, Susce suffered a broken shoulder, which sidelined him through most of the year. He torpedoed his chances the following spring after telling Tigers third baseman Marv Owen, “[y]ou’ll soon be in the sticks where you belong.”6 When Mickey Cochrane got wind of the remark, the rookie manager immediately optioned Susce to the Milwaukee Brewers in the American Association. Though he hit very well – .370-1-30 in 154 at-bats – Susce’s stay in Milwaukee proved short-lived after he nearly came to blows with outfield teammate Tony Kubek. He split the rest of the season between Beaumont and the Hollywood Stars in the Pacific Coast League.

By 1935 Susce had built a reputation as overly “spirited … to the point of militancy”7 to the extent that when the Tigers offered Brewers manager Allan Sothoron the option of taking the 27-year-old catcher back, the offer was declined. Susce was sold to the Toledo Mud Hens in the American Association, where, despite an all-star campaign, he again wore out his welcome after refusing a pinch-hit assignment. Toledo manager Fred Haney immediately suspended him for the rest of the season.

Susce earned all-star honors in each of the next three seasons while moving among five clubs (mostly in the Texas League). More importantly, over this time he developed into a fine defensive catcher. “Susce is one of the best receivers in the minors,” said The Sporting News contributor Charles J. Doyle. “[F]or some reason the scouts pass him up … [yet] yell about the shortage of catchers.”8 After the 1938 season Susce arranged his release from the Tulsa Oilers in order to negotiate directly with the major-league clubs.

Susce found a quick welcome from his hometown. After the Pirates traded veteran backstop Al Todd to the Boston Bees in December 1938, their roster consisted of two catchers who had averaged fewer than 60 games per season over the preceding three years. On February 15, 1939, Susce signed with the Bucs. Given an opportunity to compete for the starting job, he ended up serving behind the catching platoon of Ray Berres and Ray Mueller and did not get into a game until August, when the pair were sidelined by injury and illness. He had just one hit in his first 16 at-bats and barely climbed above .200 with a 3-for-3 day at the plate on the last day of the season.

Though Susce reported to Pirates spring training in 1940, his fate was likely sealed by the club’s October 1939 acquisition of Spud Davis. Susce was released by the Bucs on March 20. He was picked up by the St. Louis Browns the next day. The move was a surprise to many observers; the Browns skipper was Fred Haney, the manager who had suspended Susce five years earlier. But coming off a 111-loss season in 1939, the club seemingly had few options. Moreover, Susce’s improved work behind the plate included the ability to handle the knuckleball – a much-needed skill after the club acquired 36-year-old knuckler Johnny Niggeling. In 1940 Susce made a career-high 61 appearances for the Browns before being released at the end of the season.

Parallel events unfurling more than 500 miles to the northeast would have a major effect on Susce’s future. After Cleveland Indians manager Ossie Vitt resigned following the 1940 season, the Indians were in the hunt for a new skipper and coaching staff. In January 1941 they hired Susce as their bullpen coach and, if necessary, spare receiver. Over the next four years Susce appeared behind the plate 35 times, briefly holding down the starting job in 1944 before he was sidelined by injury. But his full-time responsibilities were aiding in the development of his younger assigns and he took this job very seriously. Susce also provided the club with “a top-flight bench jockey,”9 and even with his advanced age he was still quite capable of picking a fight. In 1943 he suffered a broken nose and damaged eye, the likely result of this very propensity, and years later reportedly threatened to take on an entire team singlehandedly. Susce also had an amusing reputation among the men in blue. In 1942 he capably filled in as an emergency spring-training umpire and did a fine job. “I don’t know why he wouldn’t,” cracked umpire John Quinn. “He umpired from the catcher’s position for 19 [actually up to that time just 13] years.”10

In 1942 Susce was reunited with his first professional manager, Burt Shotton, in guiding 24-year-old player-manager Lou Boudreau through Boudreau’s inaugural season as a skipper. With the exception of 1948, when Susce spent one season as manager of the Indians’ Class-D affiliate in the Pennsylvania-Ohio-New York League, he remained in Cleveland through most of Boudreau’s tenure as the Indians manager, later reuniting with the future Hall of Famer in Boston and Kansas City as well. “Susce was a force in the formation of the Boudreau dynasty,” said Cleveland Press sports editor Franklin Lewis.11 Arguably Susce might have relished the opportunity to remain in Cleveland throughout his entire coaching career had a dustup not developed regarding one of his many athletically inclined children.

Shortly before launching his professional career Susce had married Pennsylvania native Anna Theresa Pendro. A year his senior, Anna worked for the National Biscuit Company (now Nabisco) which sponsored a semipro club in Pittsburgh. They met while both attended one of its games. The union produced two daughters and four sons, with three of the boys eventually surfacing among baseball’s professional ranks.12 George Daniel, Susce’s eldest son (a/k/a “Junior”), was a standout baseball player at his father’s alma mater, Schenley High School. A superb pitcher and hitter, Junior was invited to work out at Cleveland Stadium on numerous occasions as the Indians aggressively pursued him. But in January 1950, after graduating from high school the previous June, Junior instead signed with the Boston Red Sox. Shortly after the signing, Susce was released by Cleveland. “[W]e should have received better treatment than that from a fellow who had been part of our Indian family as long as George had,” complained Indians GM Hank Greenberg.13

Susce followed his son into the Red Sox fold and was appointed manager of the club’s Marion (Ohio) affiliate in the Class-D Ohio-Indiana League. On June 30, 1950, one week after Steve O’Neill replaced Red Sox manager Joe McCarthy, Susce was advanced to the parent club as Boston’s bullpen coach (he and O’Neill had developed a close friendship as fellow coaches in Cleveland). Susce was reunited with Boudreau when the latter replaced O’Neill in 1952 and followed the future Hall of Famer to Kansas City after a dismal 69-85 Red Sox finish in 1954. (Ironically Susce’s dismissal came shortly after the Red Sox purchased his son’s contract from their Triple-A affiliate.) Susce spent two years in Kansas City, only to be released under circumstances eerily similar to his Cleveland departure. In 1956 Susce’s second oldest son, Paul, was an All-American pitcher at Auburn University. After his graduation that spring, the Athletics aggressively pursued the youngster. When Susce insisted that the club offer his son a three-year contract, management balked and Paul signed with the Pirates. Susce was released shortly thereafter.

Susce returned to the major leagues on April 6, 1958, replacing Milwaukee Braves bullpen coach Bob Keely (who had resigned a month earlier). He remained with the Braves through the 1959 season and stayed with the organization the following year as a coach with the Triple-A Louisville Colonels. In 1961 he was hired by the expansion Washington Senators. Except for 1968, when he signed for one season with the Jacksonville Suns in the Triple-A International League, Susce continued with the franchise through its 1972 move to Texas.

Susce’s longevity as a major-league coach stemmed in part from the friendships he forged with Boudreau, O’Neill, and, later, Ted Williams. But Susce’s credentials extended far beyond mere friendship. A tireless worker, he lived and breathed baseball. “He forced [me] to think baseball constantly,” said Cleveland catching prospect Hank Ruszkowski. “‘Make every second count,’ Susce would say. ‘If you were behind the plate right now, what pitch would you call?’ It would go on like that all day.”14 Despite a mere .228 major-league batting average, Susce was well respected for the batting tips he offered. Moreover, he was credited for his work with pitchers, particularly Art Ditmar and Bennie Daniels, who praised him in learning to throw a slider.

But above all Susce was known as a stickler for conditioning. A disciple of calisthenics, he drew commendations from slugger Frank Howard and lefty hurler Jim Kaat for his ability to keep them in top shape. In 1964, when the Senators were on a West Coast swing, Sandy Koufax sought Susce out during a period when the future Hall of Fame southpaw was suffering from a sore arm. Not everyone was on-board with Susce’s strict exercise regimen. Future Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Gordon and lefty hurler Mel Parnell were among his skeptics, and Boston manager Steve O’Neill once cracked, “Okay, George, you take the calisthenics while we watch.”15 But Susce would not be dissuaded. When he was close to 60 he could put his hands flat on the ground and touch his ankle with his nose without bending a knee. He could, it was reported, “out-exercise any fellow half his age.”16 He took his conditioning zeal outside of baseball by conducting calisthenics classes for the University of Pittsburgh track team in 1958, and the Pompano Beach Ladies Recreation Department exercise class nine years later.

After the 1972 season, Susce was released by the Texas Rangers after Ted Williams begged out of the final year of his managerial contract. The agile 65-year-old tried to secure another major-league coaching job, to no avail. In 1974 Susce helped in the conditioning of the Chicago White Sox during spring training. Observing his regimen, manager Chuck Tanner remarked, “[W]atching him go through exercises every day, I have to believe this man’s never going to die.”17 In September of that year Susce worked as an instructor at the Ted Williams Baseball Camp in Lakeville, Massachusetts.

In 1950 Susce had moved his family from Pittsburgh to Sarasota, Florida. He spent many an offseason in construction and on at least two occasions barnstormed with the famed all-star squads of Dizzy Dean (1934) and Bob Feller (1946). He had always made time for youth baseball programs but, after his wife died of cancer in 1973, Susce immersed himself deeper into these programs. “I get a bang out of it,” he said. “I’ve always enjoyed seeing somebody improve. All my life, I’ve been trying to help people. … [The] busier I am the better.”18 In 1977 Susce married a divorcee, Brooklyn, New York, native Jean Eva (Urbanowicz) Percy, but the union ended in divorce seven years later.

A strong family man, in the early morning of February 12, 1947, Susce had to rush his wife and children out of their Pittsburgh home when the house caught fire. Caused by an overheated furnace, the fire was quickly contained. Eight years later the importance he placed in family became even more clear when Susce listed them as his hobby for the Athletics’ press programs. “I figure a hobby is what you like to do most in your spare time. There’s nothing I’d rather do with it than to spend it with my family. So that must be my hobby,” he explained.19

Susce established a wide network of friends both in and out of baseball. With a keen sense of humor, he was much prized on the rubber-chicken circuit in both western Pennsylvania (where he shared podiums with Hall of Famers Stan Musial and Honus Wagner) and Florida. Susce was also very generous with his time. In 1946 he accompanied his Indians teammates to Cleveland’s Crile Veterans Administration Hospital to cheer the veterans. In the years following he participated in countless old timer’s games – often accompanied by his sons – that benefited the Hospitalized Veterans Fund, the March of Dimes, and many youth baseball programs. In 1966 Bob Addie wrote in The Sporting News that Susce was the genuine article, the “ ‘Good Kid,’ as generations of ball players from Abner Doubleday’s time have called [him].”20

Susce contracted a lung ailment that led to his passing in Sarasota on February 25, 1986. Despite his advanced age (78) his death came as a shock to his immediate family because Susce never smoked or drank and remained in top physical shape. He was buried at Sarasota Memorial Park. Two decades later his son Paul, then a baseball coach and teacher at George Wythe High School in Richmond, Virginia, helped coordinate with local police and parks and recreation departments the establishment of a youth baseball program for at-risk children. Paul played a pivotal role in renaming the program, formerly known as Strike Out Substance Abuse, in honor of his father: The George Susce “Good Kid” Clinics and Camps.

In 1940 Susce had nearly half of his 268 major-league at-bats playing for the lowly St. Louis Browns. Considered at best a third-string catcher, as a young man Susce negated his chances of a longer career with his firebrand nature. He eventually mellowed to become one of the most endeared and longest-serving coaches in baseball.

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com, and conducted two interviews:

George Susce interview with Dr. Eugene Murdock, January 4, 1980 (bit.ly/29Hs4mn).

Paul F. Susce interview, July 8, 2016.

The author wishes to thank SABR member Bill Mortell for his valuable research.

Notes

1 “Strategy – Sometimes It’s Smart, Sometimes It’s Senseless,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1955: 14.

2 Ed Pollock, “Playing the Game – George Susce Is a Family Man Now,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1955: 20.

3 Dan Rooney, the brother of future Pittsburgh Steelers owner Art Rooney, was among Susce’s high-school teammates.

4 “George Susce … There Was Only One Way to Play the Game,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, May 29, 1974: 35.

5 Baseball-Reference suggests Susce split the remainder of the 1930 season between Kansas City and Newark, New Jersey, a matter the author was unable to verify.

6 Edgar G. Brands, “Between Innings,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1934: 4.

7 “Ginger Snap for the Tigers,” The Sporting News, November 17, 1932: 1.

8 Charles J. Doyle, “Buc Fan Consensus Supports Traynor,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1937: 3.

9 “Publications,” The Sporting News, May 15, 1941: 6.

10 “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1942: 8.

11 Franklin Lewis, “Susce’s Departure Marks Conclusion of Another Era,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1950: 5.

12 The sports bloodline did not end there. In 1968 Susce’s grandson appeared in the College World Series before launching a three-year professional pitching career. In the 1950s Susce’s daughter Helene did promotional work for KDKA-Pittsburgh, the broadcast station for the Pirates; she was briefly engaged to a grandson of Connie Mack before marrying Boston College fullback and Detroit Lions draftee Emidio “Turk” Petrarca. The author discovered a Larry Susce pitching for the Palestine Pals in the East Texas League in 1938 but was unable to make a familial connection.

13 Ed McAuley, “Indians Release Coach Susce; Accepted Red Sox’ Bid for Son,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1950: 5.

14 Hal Lebovitz, “Embree Acts on Top by His Ex-Roomie,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1948: 14.

15 Stan Baumgartner, “Knicknacks Nixed for Phils’ Training,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1953: 15.

16 Bob Addie, “Pilot Gil Lauds Work of Nat Tutors – Rehires All Five,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1964: 24.

17 “George Susce … There Was Only One Way.”

18 Ibid.

19 Ed Pollock.

20 Bob Addie, “Capital Coaches Earn Repeat Engagement,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1966: 22.

Full Name

George Cyril Methodius Susce

Born

August 13, 1907 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

February 25, 1986 at Sarasota, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.