Beans Reardon

“When Mr. Reardon speaks you are under the impression that he has just spit out a hand grenade.” — Harry A. Williams, Los Angeles Times1

Beans Reardon learned a lot about umpiring at the age of 16 when he worked as a riveter’s assistant. “Riveting was good education for umpiring,” he recalled. “If I didn’t make the rivet hot enough the riveter would cuff me over the face with his leather glove and cuss me out. As a result, I was pretty good with those cuss words and rough work when I decided to try umpiring.”2

Beans Reardon learned a lot about umpiring at the age of 16 when he worked as a riveter’s assistant. “Riveting was good education for umpiring,” he recalled. “If I didn’t make the rivet hot enough the riveter would cuff me over the face with his leather glove and cuss me out. As a result, I was pretty good with those cuss words and rough work when I decided to try umpiring.”2

The self-proclaimed “last of the cussin’ umpires,” Beans Reardon led a remarkable life both inside and outside of the baseball diamond. He was a small but scrappy Irish kid from the Boston area who learned never to back down from a fight. His grittiness carried him through the tough neighborhoods of Los Angeles and his days constructing boilers and swinging a pickaxe. He found his place in the sandlots around Los Angeles, where his tough but fair demeanor was discovered as the stuff umpires were made of. Reardon had a right arm that would call players out, or throw a fist when needed in the days when donnybrooks were common. With his distinctive polka-dot bow tie, he became one of the most visible and respected umpires over his 24-year National League career. Reardon also had cameo appearances in the early years of Hollywood, befriended celebrities, and was featured in a Norman Rockwell painting that placed him on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. He left umpiring at an early age because he could make more money selling beer, but treasured his surplus of umpiring stories, which he was delighted to share for the rest of his life. He followed his own advice: “Hustle, be on top of plays, know the rules, and be honest with yourself.”3

John Edward Reardon was born on November 23, 1897, in Taunton, Massachusetts, the son of William F. and Margaret (Ennis) Reardon. Both paternal and maternal grandparents had emigrated from Ireland. William Reardon was a dyer and foreman in a cotton mill, and the part-owner of a saloon. William was injured as a catcher in a 1910 semipro game when, not wearing a chest protector, was hit by a foul ball above his heart. His injuries led to his death from a “tumor of mediastinum” in 1913 when John was a child.4 John’s older brother, Bill, attended college, but John did not. “I never graduated from any place but grammar school. … I wasn’t the best scholar who ever lived,” Reardon said.5

Reardon learned his brute honesty from his mother, who impressed upon him not to tell a lie. “I’ve always been a little thickheaded and quick to tell somebody to go to hell. I got sent home from school one time for calling a nun an SOB. I don’t know why I’m like that. Maybe I’m just honest,” Reardon said.6 At 14 he worked at the Reed & Barton silversmith shop in Taunton.7 He loved baseball, but was undersized. “I had to stand twice in the same spot to make a shadow,” he wisecracked.8 He attended baseball games in Boston, and played for the Young Red Wings youth team in Taunton, which won the 1912 city championship. Squeaky, as he was called, played right field.9 Reardon made up for his small size by being a solid, speedy fielder. He was not content playing in games with kids his own age, so he played on semipro teams when he was 15. Reardon’s mother remarried and the family moved to Los Angeles when he was 16.10 By the time he was 17, he had thrown his arm out, and from then on concentrated on being an umpire.11

“We lived in Boyle Heights, which was a pretty rough section of the city,” Reardon said. “I went to work as a messenger boy, riding a bicycle. When I turned 18, I went to work as a boilermaker’s apprentice in the Southern Pacific Railroad shops.”12 This neighborhood toughened Reardon even more for a future umpiring career. “It was on the East Side and there was a mixed population of Irish and Jews … and it was plenty tough. … You had to either fight or at least be willing to fight. If you didn’t you’d just have to move, that’s all.”13 He started umpiring games for his church team at St. Benedict’s. Soon, he was umpiring in sandlots all over Los Angeles. He would umpire and play in the railroad league games held over the noon lunch break.14 This was where he acquired his nickname of Beans.

“Whenever people asked me where I was from, I told them Boston because I figured nobody in California knew where Taunton was. So one day, when I came up to bat, Lee Allen, a fancy Pullman car painter, yelled, ‘Come on, Baked Beans, old boy, hit one now!’ The crowd picked it up, and from then on everybody called me Beans.”15

Reardon was befriended by Harry Hammer, a blacksmith who was a catcher on a semipro team, and soon Reardon was traveling with the team, helping wherever needed. One Sunday in Pasadena, California, an umpire was needed. Hammer suggested Reardon, saying, “That kid can umpire.” Reardon umpired the game, and then was offered a job umpiring every Sunday for $3 per game. Reardon demanded another quarter for carfare. “Every Sunday he’d put six half-dollars right in the middle of my locker, and I’d say, ‘Another quarter,’” Reardon recalled. “I always had to battle him for the other quarter.”16

Players often found Reardon jobs in the semipro leagues, saying, “Take care of the kid; the little SOB can umpire.”17 Eventually, he was making more money as an umpire than as a boilermaker. During World War I, Reardon went to the San Pedro shipyards as a boilermaker’s apprentice, and also umpired games there. In 1918 he umpired in the War Service League for $7.50 per game, with an $11 outfit, his first umpire uniform.18

Reardon moved to Bisbee, Arizona, in 1919, being promised he could find umpiring jobs while working a “soft” job in the copper mines. “Soft job, hell!” he recalled. “They put me to work ‘mucking’ on a ‘slope’ 1,400 feet underground. We’d dig out the ore with a pickaxe and shovel it into a big shaft close by. The boss told us to be careful not to step in that hole because it was 200 feet deep. It was damned hard work. … Had to string our lunches over a beam in the shaft to keep the rats from eating them. The rats were big as tomcats. … After three or four days I wondered what the hell I was doing there.”19 The Sporting News mentions Reardon umpiring in Bisbee for a weekend old-timers’ league.20 Reardon returned to Los Angeles shortly thereafter.

Reardon was umpiring a game in Pasadena involving the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. Angels manager Wade “Red” Killefer encouraged him to think about a career in umpiring. “You’ve got the ability and if you’ve got the courage, you don’t need anything else,” Killefer said.21 They contacted Sammy Beer, a former Angels pitcher who was in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Beer found Reardon an umpiring job in the Class-B Western Canada League, making $250 a month plus expenses. “But that was better than swinging a 16-pound sledgehammer in the boiler shop 54 hours a week for 25 cents an hour.”22 Reardon was 22, and now a professional umpire. Reardon was extremely frugal, and saved $750 out of his total $1,000 salary for the four months. The league president asked him what he had been living on. Reardon winked and said, “On my good looks.”23

Reardon’s Calgary days were tough, with few amenities. “You had to dress in the groundkeeper’s shack, where he kept his equipment,” he recalled. “There was no shower, either. You just put your good clothes on over the dirt and sweat till you got back to the hotel. … In my day, you got no cab money. You had to wrestle your bag on a streetcar, dress in a shack that looked like an outhouse, umpire yourself with probably only a six-inch flag as a foul marker 450 feet from the plate.”24 There was also the rowdiness of the fans who “would follow you down the street and yell at you. … I had several street fights because I couldn’t tolerate the names they were calling me.”25

“You didn’t have enough money for food, so you just hustled, that’s all,” Reardon said. “I stayed in a place in Moose Jaw across the street from the railroad station; had to run down the hallway to the bathroom. Umpires didn’t get enough money in those leagues to rent a place with a toilet in your room. … You had to be tough to survive.”26 Because many umpires quit after just a few games, Reardon’s fare home was guaranteed only if he lasted the entire season. After one game, policemen offered to escort him through a back way in the park to avoid the ferocious fans waiting for him at the gate. Reardon rejected the offer, saying, “I didn’t sneak in, and I won’t sneak out.”27 “I came in the front gate and that’s the way I’m going out, and if one of those fresh thugs makes a move at me, I’ll flatten him. If you want to come with me, all right. But I don’t need you,” Reardon told the gendarmes.28

Reardon never backed down from a fight. Back in California, he umpired a Winter League game on November 21, 1920, between the Los Angeles White Sox and an all-star team. “Umpire Beans Reardon put down a slight demonstration of Bolshevism in the first of the sixth inning, when he called Tony Boeckel out at the plate on Charley Moore’s throw to Ray,” the Los Angeles Times reported. “Irish Meusel dissented, whereupon Beans pulled off his mask and chest protector and did a Jack Dempsey that made Irish wince with envy. About 25 cops intervened and pressed all the bellicose disposition out of both Meusel and Reardon and the game went merrily on.”29

Reardon returned to Canada in 1921, and met New York Yankees scout Bob Connery, who was traveling through Canada looking for prospects. Connery recommended Reardon to PCL President William H. McCarthy, who hired him in 1922, telling him, “Now, I’m going to tell you something, Beans. We want umpires in this league, we don’t want fighters.”30 Reardon did have a fistfight in San Francisco with player Paddy Siglin,31 and newspapers carried pictures of the encounter. He also fought with manager Charlie Pick of Sacramento, who, after Reardon had thrown a player out, “came charging out of the dugout after me,” Reardon recalled. “He threw a punch at me, but I was ready for him and we tangled. … It was a better fight than many a one I’ve paid money to see since. We both got in some pretty good licks.”32 “Yes, I had a reputation as a fighter. But I really wasn’t a fighter. I had some fights, but I didn’t enjoy them. They just couldn’t be avoided.”33

In Portland, Oregon, fans would regularly throw seat cushions at Reardon at the end of the game. When asked if they ever threw the cushions before the game, Reardon joked, “Naw. Those fans up there wouldn’t throw away a cushion they paid a nickel for until they had gotten their money’s worth out of it.”34

Reardon befriended major-league umpire Hank O’Day, and they would travel to the racetrack in Tijuana, Mexico, on Sundays in Reardon’s Hudson Speedster. O’Day recommended Reardon to National League President John Heydler, and Beans was hired in November of 1925, after four years in the PCL.35 Heydler warned him to never be in any fights. Reardon objected, saying that being about 5-feet-6 and 130 pounds, you have to be prepared. Heydler responded, “Okay, but promise me you won’t throw the first punch.”36

At the train station on April 9, 1926, Reardon waved to the crowd that came to see him off. “I’ll sure do my darnedest to make good back there,” he yelled. The train was heading to St. Louis, and Reardon’s major-league umpiring career had begun.37

“Reardon has curly brown hair, blue eyes, and a square cut chin. He speaks with a nasal twang, which is his birthright. He comes from Massachusetts – from Taunton,” wrote Damon Runyon.38 Reardon’s career could have ended early when a play in Pittsburgh led to Brooklyn’s Chick Fewster having some unkind words for him. The umpire spun him around and would have hit him if Rabbit Maranville hadn’t grabbed his arm. “Rab probably saved my job,” Reardon gratefully acknowledged.39 On a return trip to Boston, a delegation from Taunton came to Braves Field to welcome “Squeaky” home, including Mayor Andrew J. McGraw, Police Chief John P. Duffy, and former teammates from the Young Red Wings, who made a presentation on “Reardon Day.”40

One memorable game in Reardon’s rookie year occurred on August 15, 1926. Brooklyn loaded the bases when Babe Herman hit a fly ball off the fence in right field. One run scored, but runners Dazzy Vance, Chick Fewster, and Herman all wound up on third base. “Damn it, wait a minute. I got to figure this out,” Reardon yelled. He awarded the base to Vance and called Fewster and Herman out. “That’s it. The side’s out. Let’s play ball, fellas.” Herman doubled into a double play.41

Reardon never got along with Bill Klem, chief of the National League umpires. He disregarded Klem’s order for NL umpires to wear a chest protector under their coat. Reardon wore the outside inflated protector used by American League umpires. Reardon said he promised his mother he would never get hurt or suffer an injury due to a lack of protection.42 National League umpires were also asked to wear a four-in-hand tie, but Reardon wore a blue and white polka-dot bow tie for his entire career.43

In 1927 Reardon had a cameo in the MGM silent film Slide, Kelly, Slide, along with players Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri.44 In 1928 he was cast as an umpire in the Richard Dix film Warming Up, which included several major leaguers. Warming Up was Paramount’s first film with sound. In the transition between silent films and talkies, production companies were experimenting with synchronizing sound into the film. While there was no dialogue in the film, post-production editing added the crack of the bat and the roar of the crowd to the action on the field.45 This film is in the category of “goat-gland films.”46 No copy of the film is known to exist.

In August 1929 Reardon had surgery for appendicitis. Under spinal anesthesia, he was able to watch the operation as it took place. Before it concluded, Reardon wisecracked, “Doc, you’d better take a good look around in there and if you see anything else I don’t need, take it out, too.”47 Reardon missed the rest of the season and a chance to umpire in the 1929 World Series.48 He recovered, and got married in Los Angeles on November 23, 1929, to Marie Lillian Schofield.49 The couple settled in Los Angeles.50

Reardon umpired in the 1930 World Series, and considered it his biggest thrill in baseball. It was the first World Series he had ever seen, and he wore the commemorative ring for the rest of his life.51 He joined a group of major leaguers in a tour of Japan in October of 1931.52 “No Japanese player ever talks back, none ever disputes a decision and not even the spectators razz the umpire,” he said.53 Reardon lost 10 pounds, however, not stomaching the raw fish and eels.54

Reardon umpired the 1934 World Series as “a man with the poise of a Supreme Court judge. … He will jerk his thumb with the austere finality of a Nero.”55 He felt anxiety before a World Series game. “I don’t say I never called a wrong one – maybe plenty of ’em wrong. But I’d hate to call one in the Series when so much is riding on every pitch and every slide. … The night before the big game always gives me the jitters.”56 Reardon was umpiring first base in Game Seven when Ducky Medwick’s hard slide into Marv Owen at third base led to a brawl and fans throwing debris on the field. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis removed Medwick from the game.

Reardon was also remembered for his wit and humor. Philadelphia Phillies manager Jimmie Wilson argued with him on a caught-stealing call, yelling, “You know something, Beans. There are fifty thousand people in the ballpark and you’re the only SOB who thinks he’s out.” Reardon replied, “Yes, but I’m the only SOB who counts.” Wilson returned to the dugout laughing.57 A disgusted Hack Wilson once threw his bat up into the air after striking out. “If that bat comes down, Hack, you’re outta the game,” Reardon bellowed.58 National League players often referred to Reardon as having “rabbit ears,” claiming that you could whisper something at the Polo Grounds in New York and he would hear it while working a game in Boston.59 Casey Stengel was managing in Boston and took exception to Reardon’s ball-and-strike calls. Making his way up two of the three dugout steps, Stengel debated whether to come out and argue. Reardon warned him to stay right where he was. Finally, Stengel remarked, “I quit. You’re the only bloke I’ve ever seen who can umpire and argue at the same time.”60

Reardon was being accosted by a loudmouth fan one day, and looked into the crowd to identify him. As fate would have it, the fan was Reardon’s waiter at a restaurant that night. He sheepishly took his order, and was extremely courteous to the umpire. Reardon asked the man why he, a total stranger, had been called such terrible names. “Well,” the fan muttered, “I am an old man and I have slaved all my life. My bunions burn my feet. I am browbeat 12 hours a day. The chef curses me at one end; the customers throw scorched eggs in my face at the other. I go crazy. My only relief is to go to the ballpark and holler at you.”61

Reardon’s reputation for a no-nonsense, profanity-laced style became legendary. A player once asked NL President Ford Frick, “Mr. Frick, a ballplayer gets fined $50 for swearing at an umpire, right?” Ford concurred, and when the player said Reardon had sworn at him, Frick remarked, “Don’t be mad. Consider it a compliment. That’s like having anyone else say ‘hello’ to you.”62

Reardon enjoyed the conflicts. “I never liked to toss ’em out of the game. If I had, there wouldn’t have been anybody left to cuss at.”63 “If a player swore at me, I’d swear back at him. It was either that or chase him out of the game. And if I did that, I had to make out a report, and I’d rather leave him in.”64 Bob Broeg wrote in The Sporting News that Reardon would “rather exchange sulphuric insults than pull his rank. Reardon’s four-letter forensics were never more eloquent than when he and Frank Frisch were raising their penetrating pipes in cheek-to-jowl arguments which were classical.”65 Frisch was once ejected by Reardon and fined $50. Later that night, Frisch phoned Reardon and invited him to the bar. Reardon recalled, “It not only cost him $50 and five rounds of beer, but I borrowed his car for the evening and then told him to phone the garage and tell ’em to fill ’er up.”66

Reardon appeared in the 1935 Mae West film Goin’ to Town,67 and also received $50 a day “as technical advisor when they were shooting baseball films.”68

Fans in Cincinnati showered Reardon with pop bottles after he made a call against the home team on July 17, 1935. “The shower of glassware from the right field pavillion furnished the most exciting interlude in the long game which was marked by much bickering on both sides. The missiles were aimed at Umpire Beans Reardon because of his ruling in the seventh inning…” wrote the Associated Press.69 NL President Ford Frick fined umpires Reardon and John “Ziggy” Sears for inciting the crowd.70

Still, Reardon was grateful he hadn’t been working in the copper mines all those years. “Pretty soft job you have at that, Beans,” someone yelled to him on the New York subway. “Yeah!” Reardon hollered back. “Let ’em yell at me for two hours every day, and I have the rest of the time to myself.”71

Reardon was behind the plate for Babe Ruth’s “last hurrah” on May 25, 1935, when the Bambino, now with the Boston Braves, hit his final three home runs in a game at Pittsburgh. He also ejected Ruth in 1938, when he was coaching at first base for Brooklyn.72

Reardon would attend horse-racing events at Santa Anita, California, with celebrity friend Al Jolson, who could rarely match Reardon’s knack for betting on the photo-finish winner. “I love to bet on what the photo will show on a photo-finish horse race,” Reardon boasted. “I’ll give any odds to any takers. But I don’t get many takers. Guess people know I spent a lot of years calling quick decisions on fast action. … I can pick the winner by a whisker!”73 However, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis prohibited Reardon from gambling.

Reardon stayed busy in the 1935 offseason. “Now I had two weeks’ work with Mae West on that new one that’s coming out, Klondike Lou, or something like that. I had another two weeks in that grand opera thing with Gladys Swarthout and Jan Kiepura, acting like a stagehand or an electrician. It was easy for me.”74 The Mae West feature was eventually titled Klondike Annie, and also included an appearance by Jim Thorpe.75

“You would have been a fine asset to baseball if you had stayed in the movies,” Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel remarked to Reardon in 1936.76

Reardon suffered two sunstrokes during the 1936 season, and was ordered by doctors to take the rest of the year off. “I wasn’t feeling very good about it,” he remembered, “until I saw the paper the next day. There I read that the same day I collapsed a camel of Barnum and Bailey’s circus passed out while they were taking it to a train. … It died two days later. I knew then that if the heat killed off a camel, maybe I could take it better than I thought.”77

Reardon appeared in the 1937 film Internes Can’t Take Money, starring Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea.78

Apparently Reardon was also a landlord in the Los Angeles area; The Sporting News wrote that tenants of his apartment building were suffering from the unusually cold winter and “have demanded that Beans install bathtubs before another winter rolls around. They say they have no place to store their coal.”79

Reardon umpired in the 1943 World Series. On a train trip from New York to St. Louis, a thief reached under the pillow on his Pullman berth and swiped his wallet, containing $300. Reardon saw the intruder slipping away and cornered him, leading to a scuffle in which he sprained his finger, but got his wallet back. The man locked himself into a lavatory, and then jumped out a window while the train sped along. “I had a heck of a time,” Reardon recalled. “I was trying to get my money back and hold up my pajamas at the same time.”80

In late 1944 Reardon joined a USO baseball tour to the South Pacific to entertain servicemen in World War II. “We’d put in 16 hours a day talking baseball to servicemen and answering questions. They just couldn’t get enough,” Reardon said. He stole the show with his tales of umpiring.81 He returned in January of 1945 and traveled to Chicago to speak to owners of major war plants in the city.82 “Before I started on the trip (to the Pacific) I thought I was tough,” Reardon told his audience. “Now I know I’m not tough at all. How anybody can think he is tough, after seeing what those kids in the South Pacific are going through every day, stops me. I have seen kids without eyes, without arms, without legs – and without life. Just looking in on their courage makes me blush that I ever thought I was tough, but mighty proud that I was born in the same country from which they sprang.”83

Reardon was an alternate umpire for the 1946 World Series, which paid him $750 plus expenses. He arrived mere moments before Game Six in St. Louis as his train was either delayed or broke down (according to two different reports) and he took a 100-mile cab ride from Effingham, Illinois, which cost him $25.84

Reardon loved to have a good beer, and would walk out of a bar if they didn’t have Budweiser. His brand loyalty led to a second career for him. Budweiser offered him a job making advertisements and sharing his baseball stories in talks. In 1946, Reardon bought the Budweiser distributorship in Long Beach, California.85

On July 20, 1947, at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, St. Louis led Brooklyn 2-0 entering the ninth inning. Ron Northey of the Cardinals hit a long fly ball to center field that hit the top of the wall. As Northey approached third base, Reardon signaled home run, which slowed Northey’s pace and led to his being thrown out at the plate. The Cardinals protested the game, claiming deception by Reardon.86 Brooklyn scored three in the bottom of the ninth to win the game, 3-2, but NL President Frick ruled the game a tie, despite the fact there was only one out recorded in the bottom of the ninth, “in the name of common sense and sportsmanship.” Brooklyn won the makeup game on August 18.87

A fight broke out on Opening Day in Cincinnati, April 19, 1948, after a play at second base. A fan tussled with Reardon, while fellow umpire Jocko Conlan wrestled with a photographer.88 In October of 1948, Reardon’s souvenir warehouse was robbed – the burglar stealing five autographed baseballs. “The only baseballs they didn’t take were the ones with my autograph,” he reported.89

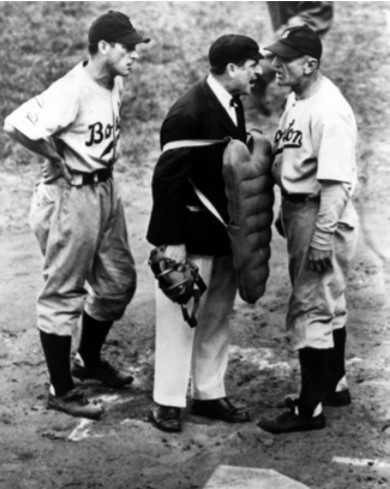

Also in 1948 a photographer appeared at Ebbets Field and took pictures of Reardon and fellow umpires Larry Goetz and Lou Jorda, as well as Brooklyn coach Clyde Sukeforth and Pittsburgh manager Bill Meyer. These were reference photographs Norman Rockwell would use to paint the cover of the Saturday Evening Post for April 23, 1949.90 The painting, named Tough Call, Game Called Because of Rain, or Bottom of the Sixth Inning, depicts three umpires eyeing the rainfall. Lauren Applebaum writes, “Rockwell pays tribute to baseball’s uncelebrated heroes, the umpires, who dwarf the ballplayers during a game. …”91 Reardon stands in the center, holding his chest protector and mask in one hand, and holding his other hand palm-up, catching raindrops.

In July of 1949, Marie Reardon was robbed in their home in Long Beach, California. She was bound and gagged in a closet while the robbers made off with $4,200 in jewelry. She was able to keep her wedding band when she pleaded, “It has never been off my finger.”92

The 1949 season was Reardon’s last as an umpire and he would now devote himself totally to his beer distributorship. “I’m getting out of umpiring. …Umpiring is a good job and I’d do it again if I had my life to live over. I have to get up at 7 A.M. to take care of my business here. When I’m umpiring, I get out of bed at 10 A.M. and work a couple of hours a day. You can’t beat those hours. And my salary comes in five figures.”93 Reardon retired after the 1949 World Series, but umpired at the Latin Olympics in Guatemala in late 1949 and some spring training games in the spring of 1950.94

Reardon appeared on NBC Radio in an episode of Ralph Edwards’ This Is Your Life on April 19, 1950.95 In his post-umpiring years he also wrote a column called “The Umpire” for the Newspaper Enterprise Association, which was carried in newspapers across the country. The Q&A style included random baseball trivia and umpiring questions sent in by readers.96

Marie Reardon died of a heart attack on March 9, 1953, at the age of 57. The couple had no children, but Marie had a grown son, Stanley Schofield, from a previous marriage.97 Reardon continued to run his beer-distribution business, which was reported to be profiting $2 million yearly in 1953.98 On July 31, 1953, Twentieth Century-Fox Films released the motion picture The Kid From Left Field,” starring Dan Dailey and Anne Bancroft. Reardon portrayed an umpire.99

On June 28, 1954, Reardon married Nell Eugenia Schooler, who owned an aluminum-window business that provided windows for the United Nations building. She was an avid painter who had studied art in the Netherlands, and she painted a portrait of Nancy Reagan that hung in the White House.100 Along with her paintings, the Reardons’ den included Beans’ whiskbroom, polka-dot bow ties, the Rockwell painting, and pictures with Gary Cooper and other movie stars. There was also a large picture of a nude Mae West. “She always sent him a copy of that picture every Christmas,” Eugenia said. “No, I was never jealous.”101

Reardon appeared on the November 14, 1954, episode of The Jack Benny Show entitled “The Giant Mutiny.” The episode was a spoof on The Caine Mutiny and also included baseball managers Leo Durocher, Fred Haney, and Chuck Dressen, and pitcher Bob Lemon.102 Reardon sponsored a youth baseball team in the Long Beach Police League called the “Little Beans.”103 He sold the Budweiser distributorship in 1967 to Frank Sinatra for around $1 million but continued to work for Budweiser, making speaking appearances around the country. “Everyplace I go I run into someone I’ve known in baseball,” Reardon said.104

One of his stories involved the time he called baserunner Granny Hamner safe, but inadvertently gave the out sign. He asked Hamner if he had heard him call safe, and Hamner said yes. “I know,” Reardon told him, “but only you and the second baseman heard it and 8,000 people saw me call you out. Granny, it’s 8,000 to 3, and you’re out.” Another favorite story included a baserunning blunder by Tommy Henrich, who was tagged out. Henrich asked Reardon to let him stand there pointing his finger at the ump for a couple of minutes so fans would boo Reardon and forget Henrich’s boneheaded play.105

Eugenia Reardon traveled with her husband, calling on customers at the local taverns. “The people loved to see Beans,” she recalled. “He never tired of going out. He loved to talk. He was very witty about this funny business called baseball.”106 Beans and Eugenia frequently attended Dodgers and Angels home games. The Reardons loved art, and would often visit Paris, Eugenia’s birthplace, and she would point out historic buildings to him. The very vocal Reardon would be humbled watching his favorite artist. “He’d come out and sit three or four hours in the studio and watch me paint. He never talked at all, just watched me,” Eugenia fondly remembered.107

In 1970 Reardon was presented the Bill Klem Award for meritorious service to baseball. In response he said, ”I’m very glad to receive the Klem Award, but I’ll tell you the truth. Klem hated my guts and I hated his.”108 Reardon also sent a get-well card to old nemesis Frankie Frisch, who was hospitalized after a car accident. “When you get prayers from the bottom of the cold heart of an umpire, you should have quick results and a speedy recovery,” Reardon wrote.109

Reardon died on July 31, 1984, at the age of 86, at his home in Long Beach, after suffering from arteriosclerosis and two strokes. He is buried with his first wife, Marie, at Calvary Cemetery in Los Angeles. While he has never been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, there is a part of him there. “I loved my little blue and white polka-dot bow tie,” Reardon said. “That tie is more famous than I am; it’s in the Hall of Fame.”110

That tie could tell a lot of stories, too.

This biography was originally published in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin. It also appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Besides the references cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following sources:

Ancestry.com

Beans Reardon file at the Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Familysearch.org

Gerlach, Larry R. “Reardon, John Edward ‘Jack,’ ‘Beans,’” in David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Q-Z (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000), 1257-1258.

Notes

1 Harry A. Williams, “Bengals Belt Bees Blithely,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1921: 19.

2 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Beans Calls Himself Out as Umpire,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1949: 8.

3 Frank Graham, “Beans – the Vet Bluecoat Who Never Grew Up,” The Sporting News, December 20, 1945: 2.

4 Tom Wall, Augusta Chronicle, May 16, 1941, notes that this information was contained in a Cincinnati baseball publication.

5 Larry R. Gerlach, The Men in Blue: Conversations With Umpires (New York: Viking Press, 1980), 4.

6 Ibid.

7 Gerlach, 23. The Reed & Barton silversmith shop began in Taunton in 1824. Taunton was nicknamed the Silver City because of its many silver-industry businesses. Reed & Barton, the last remaining silversmith company in Taunton, filed for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy in February of 2015. Charles Winokoor, “Silver City No More? Taunton’s Reed & Barton Files for Bankruptcy,” Taunton Gazette, February 19, 2015, tauntongazette.com/article/20150219/NEWS/150216074/13406/NEWS/?Start=1. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

8 Gerlach, 5.

9 Kerry Keene, “Taunton Native Donned Ump’s Mask in Majors for 24 Years,” Taunton Gazette, May 21, 1994: 7.

10 Some accounts say age 14 or 15. Reardon stated 16.

11 Graham.

12 Gerlach, 5.

13 Jack Diamond, “Play ’Em Safe, Call ’Em Safe, Says ‘Beans,’” San Francisco Chronicle, January 14, 1936: 21.

14 Ibid.

15 Gerlach, 5.

16 Gerlach, 6.

17 Ibid.

18 Ralph S. Davis, “Reardon Became Ump, Without Being Player,” article of unknown origin dated April 21, 1932, in Reardon’s Hall of Fame file; “Beans’ First Job Behind Plate Paid Him Just $3,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1949: 8.

19 Gerlach, 6.

20 Edgar Munzel, “25 Years Lower Beans’ Boiling Point,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1944: 7.

21 Gerlach, 6-7.

22 Gerlach, 7.

23 Spink.

24 Munzel.

25 Ibid.

26 Gerlach, 7.

27 Gerlach, 8.

28 Graham,

29 Ed O’Malley, “Walter Mails Gets Jarring,” Los Angeles Times, November 22, 1920: 119.

30 Gerlach, 8.

31 “Paddy Siglin Loses to ‘Beans’ Reardon,” Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1922: 112.

32 Munzel.

33 Gerlach, 9.

34 “Baseball Pick-Ups Gathered From Hither and Thither,” Los Angeles Times, November 30, 1924: A6.

35 “ ‘Beans’ Reardon Goes to National League,” Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1925: B1.

36 Gerlach, 9. Reardon’s Sporting News umpire card on the Retrosheet website lists him as 5-feet-9 and 190 pounds. Other sources, including Baseball-Reference.com, and the Internet Movie Database list him as 6 feet tall.

37 “Gene Tunney Arrives; Dempsey’s Challenger Blows in as Kearns, Dorvall, and ‘Beans’ Reardon Pull Out for East,” Los Angeles Times, April 10, 1926: 11.

38 Damon Runyon, “Runyon Says,” International Feature Service, in the Harrisburg Evening News, April 29, 1926: 19.

39 Gerlach, 9.

40 “Taunton Fans Coming Tomorrow to Do Honor to Reardon, Umpire in National League,” article of unknown origin dated May 26 in Reardon’s Hall of Fame file. The Braves hosted the Giants on May 28, 1926, in Reardon’s first year, and he is listed in the box scores as umpiring that series.

41 Gerlach, 21; “Three Men on Third,” research.sabr.org/journals/online/39-brj-1977/197-three-men-on-third.

42 Michael Gavin, “Wind Bags Again Vogue With NL Umps,” Boston Record American, August 31, 1952, 18.

43 Associated Press, “Reardon to Retire as Umpire,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), October 4, 1949: 14.

44 Dan Thomas, “Big League Players in Hollywood,” Springfield (Missouri) Leader, January 30, 1927: 28.

45 “Paramount’s First Sound Film: A Newspaper Picture,” New York Times, July 22, 1928: 93. Richard Dix, the male lead, portrayed Bert Tulliver, a baseball pitcher who tries out for the Yankees. He doesn’t win a job in spring training, and endures the wrath of the team’s star hitter and villain. He works at a carnival and draws the attention of Mary Post, daughter of the Yankees’ owner, portrayed by Jean Arthur. She gets him another tryout with the Yankees, and he winds up in the “world’s series.” When the Yankees’ starting pitcher is injured, Tulliver comes on to pitch, predictably with the bases loaded and no outs. Tulliver is also distressed in believing Mary will wed someone else. But then Mary nods to Tulliver that she will marry him, which is all the motivation he needs to strike out the side, the last of which was the villain who was now playing for Pittsburgh. Tulliver was the hero and Reardon was the home-plate umpire who called the villain out on strikes. The reviewer for the New York Times, however, was not impressed. “Paramount’s first synchronized picture – ‘Warming Up’ – appears to have been done in a little too much of a hurry. The synchronization is faulty in spots, the acting is not particularly good, and the plot reads like a success story from one of the lesser magazines.” Another review from the New York Times concluded, “The synchronizing is such, however, that the smack of a ball against a bat is heard some time before Lucas (the pitcher) has finished winding up. … There is plenty of noise in the exciting parts, and music when it isn’t so exciting.” (“The Screen: The Great American Game,” New York Times, July 16, 1928: 27).

46 Goat-gland films were attempts to add sound to already completed silent films. The term came from a surgical technique developed by John R. Brinkley in which he transplanted testicles from male goats into men suffering from low libido. Movie critics used the term for describing desperate attempts to bring new life into dead films. Despite the poor review, Warming Up was popular with the public, and New York’s Paramount Theater broke existing house records. See “Grift, Goats, and Gonads: Historians Ponder the Colorful Career of John Brinkley, American Quack,” The Chronicle of Higher Education No. 16 (2002), accessed March 13, 2015; Debra Ann Pawlak, Bringing Up Oscar: The Story of the Men and Women Who Founded the Academy (New York: Pegasus Books), 2011, Anthony Slide, Silent Topics: Essays on Undocumented Areas of Silent Film (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press (2005), 79.

47 From an article of unknown origin in Reardon’s Hall of Fame file.

48 “Umpire ‘Beans’ Reardon Must Go Under Knife,” Boston Herald, August 11, 1929: 13; “Augie Walsh Sold to Chicago,” Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1929: 9.

49 “Did You Know That,” State Times Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), December 7, 1929: 10.

50 “Umpire Reardon Weds Coast Girl,” article of unknown origin in Reardon’s Hall of Fame file.

51 Keene.

52 “1931 Tour of Japan,” vintageball.com/1931Tour.html, retrieved April 12, 2015.

53 Japan Umpire’s Eden, Says ‘Beans’ Reardon,” Evening Tribune, San Diego, January 6, 1932: 16.

54 L.H. Gregory, “Gregory’s Sports Gossip,” The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), January 6, 1932: 18.

55 Henry McLemore, United Press, “Night Before the Series Plain Hell on the Umps,” Omaha World Herald, October 3, 1934: 18.

56 McLemore, 19.

57 Gerlach, 17.

58 Bob Broeg, “Beans Reardon Makes Himself Heard,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1973: 40.

59 Boston Herald, May 21, 1931: 29.

60 Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Interference of Owners Blamed for Poor Umpiring,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), October 4, 1953: 21.

61 Jimmy Powers, “Rassle Riots Beneficial,” Omaha World Herald, October 17, 1934: 13.

62 Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Reardon Still the Ump,” State Times Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), May 18, 1967: 39.

63 Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Interference of Owners Blamed for Poor Umpiring,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), October 4, 1953: 21.

64 Jeane Hoffman, “Reardon Was Cussinest Ump in National Loop,” Los Angeles Times, May 3, 1957: C3.

65 Broeg, “Beans Reardon Makes Himself Heard,” 40.

66 Ibid.

67 “ ‘Beans’ in West Film,” San Diego Union, January 20, 1935: 32.

68 “Umps Reardon in Movies,” Richmond Times Dispatch, May 26, 1935: 22.

69 “Fans Throw Pop Bottles as Giants Defeat Redlegs: Umpire Angers Paying Guests,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, July 18, 1935: 6.

70 “Umpires Given Fines by League President for Cincinnati Row,” Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, August 24, 1935: 10; Wilbur Fogleman, “On the Rebound,” Riverside (California) Daily Press, July 30, 1935: 11. Reardon challenged “the grandstand, bleachers and box-seat holders to come out collectively or in a single line of march to face him following that pop bottle shower…”

71 Harold Parrott, “Beans on the Pan!” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 25, 1935.

72 “Ruth and Grimes Put Out of Game,” Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, August 8, 1938: 6.

73 Tex McCrary and Jinx Falkenburg, “It’s Toughest Behind the Plate, Says Beans Reardon, on Last Job,” Boston Globe, October 8, 1949: 13.

74 Jack Diamond.

75“Mae West as ‘Klondike Annie’ at Roosevelt,” Seattle Daily Times, May 18, 1936, 4; “Klondike Annie,” Turner Classic Movies. tcm.com/tcmdb/title/80451/Klondike-Annie. Also in the film were boxers Ellsworth “Hank” Hankinson and Billy McGowan, as well as football player Dink Templeton.

76 Eddie Brietz, Associated Press, “Stengel and Ump Swap Fire Throughout Series,” Washington Evening Star, April 17, 1936: 49.

77 Munzel.

78 imdb.com/title/tt0029050/?ref_=ttfc_fc_tt, retrieved April 12, 2015.

79 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Three and One,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1937: 4.

80 Associated Press, “Beans Reardon ‘Pins’ Thief, Sprains Finger, but Gets $300 Back,” Boston Globe, October 9, 1943: 5.

81 Charles C. Spink, “Beans Steals the Show at Base in New Guinea,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1945: 4.

82 “Servicemen Want Major Baseball,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, January 13, 1945: 6; Walter Byers, “Aid of Sports is Sought to Speed Up War Production,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), January 19, 1945: 10.

83 Ed Burns, “Umpire Stirs Workers with Tearful Profanity,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1945.

84 Will Cloney, “Sox ‘Baby’ Set for Big Test,” Boston Herald, October 15, 1946: 17; “World Series Notes,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, October 15, 1946: 12. Reardon was seated next to NL President Ford Frick in the stadium for Game Seven in St. Louis. As Enos Slaughter scampered home from first base on a single in the eighth inning, sealing the championship for the Cardinals, Reardon began yelling, “Stop! Stop! Stop!” He later explained, “I didn’t think he had a chance to score.” Daniel W. Scism, “Sew It Seems,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, October 17, 1946: 14.

85 L.H. Gregory, “Greg’s Gossip,” The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), December 9, 1946: 2. Some even claimed Reardon told Northey to slow down, to which he responded “I was umpiring on third and when Northey thought it had gone into the stands for a home run … I was waving my arms in a circle, signaling a home run. However, I did not speak to Northey. … I want to get one thing clear and that is I didn’t tell him to slow down.”

86 Some even claimed Reardon told Northey to slow down, to which he responded “I was waving my arms in a circle, signaling a home run. However, I did not speak to Northey…I want to get one thing clear and that is I didn’t tell him to slow down.” Associated Press, Reardon Denies ‘Slow Down,’ Yell,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, July 27, 1947: 20.

87 Associated Press, “Frick Orders Replay of Card-Dodger Game,” Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1947: 10. See also David W. Smith, “The Protested Game of July 20, 1947,” in Lyle Spatz, ed., The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America: the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 201-202.

88 Associated Press, “Scuffle Spices Reds’ Win,” Boston Herald, April 20, 1948: 18. Later in the season, the umpiring crew of Conlan and Reardon had to be broken up due to the two arbiters not getting along with each other, “Umpires Troubles Increase,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), July 11, 1948: 18.

89 International News Service, “Nobody Wants His Autograph,” The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), October 16, 1948: 16.

90 “Game Called Because of Rain,” Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies.

rockwell-center.org/exploring-illustration/game-called-because-of-rain/. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

91 Lauren Applebaum, “Rockwell, Norman (1894-1978),” in Murray R. Nelson, ed., American Sports: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas (Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, 2013), 1093-1094. Applebaum writes, “(W)hile the scenario depicted in Tough Call is just a game, the uncertainty of the outcome between these opponents relates to more serious political and economic uncertainties in America at the dawn of the Cold War. As weather is an uncontrollable force that can determine the future of the game, the image is juxtaposed with a headline on the magazine cover, which reads, ‘What of Our Future?’ by American financier and political consultant Bernard Baruch. … Thus, baseball performs in a covert fashion the conflicts of our world, providing an outlet to collectively confront tension under the guise of participating in an American tradition.”

92 Associated Press, “Mrs. Beans Reardon Robbed of $4200,” Boston Traveler, July 18, 1949: 21.

93 United Press, “Reardon Undecided Whether to Quit,” Riverside (California) Daily Press, February 11, 1949: 12.

94 “Reardon, Although Retired, Goes on Emergency Duty,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1950: 9.

95 UCLA Film & Television Archive – Ralph Edwards Collection. cinema.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/REmasterlist.pdf. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

96 For instance, in one such column Reardon answered questions on how many at-bats a batting champion needs to have, how an earned run is determined, and what constitutes a wild pitch and sacrifice hit. Canton (Ohio) Repository, July 12, 1952: 7.

97 Associated Press, “Umpire’s Wife Dies,” San Diego Union, March 11, 1953: 16; “Beans Reardon’s Wife Dies in Long Beach,” Fresno Bee, March 11, 1953: 7C.

98 Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Interference of Owners Blamed for Poor Umpiring,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), October 4, 1953: 21.

99 “The Kid From Left Field” overview. tcm.com/tcmdb/title/80194/The-Kid-from-Left-Field/. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

100 Dick Wagner, “Umpire’s Wife Lives With Memories of Beans and Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, January 14, 1988: SE10.

101 Wagner.

102 Jack Benny Program Season Five, Episode Four. tv.com/shows/the-jack-benny-program/the-giant-mutiny-126554. Retrieved March 30, 2015. William Buchanan of the Boston Herald was less than awed by the episode, writing, “Benny, Durocher, and Umpire Beans Reardon hit singles, but not enough runs were scored to call this show a real winner.” William Buchanan, “Benny Scores Too Few Runs,” Boston Herald, November 15, 1954: 27. Benny enjoyed the episode and praised the performances of Durocher and Reardon, saying that “Beans Reardon is another good one who would make a good actor.” Wayne Oliver, Associated Press, “Benny Enthuses Over Durocher’s TV Skit,” Aberdeen (South Dakota) Daily News, November 19, 1954: 9.

103 Bob Van Scotter, “ ‘Miss Game?’ ‘No,’ Answers Former Ump,” Rockford Morning Star (Rockford, Illinois), April 15, 1959: C1.

104 Earl Gustkey, “Beans Reardon Still Calls ’Em as He Sees ’Em,” Los Angeles Times, August 3, 1973: D14. Reardon claimed the $1 million selling price, although other accounts vary. Gerlach, 23.

105 Lynn Mucken, “Beans’ Story String Relates Funny Side of Gentlemen in Blue,” The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), July 26, 1972: 6.

106 Wagner.

107 Wagner.

108 Chauncey Durden, “Sportview,” Richmond Times Dispatch, February 18, 1970: 24; Sports Illustrated, November 15, 1989. si.com/vault/1989/11/15/121035/1970. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

109 Bob Broeg, “An Old Friend’s Letter to Frisch,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1973: 34.

110 Gerlach, 13.

Full Name

John Edward Reardon

Born

November 23, 1897 at Taunton, MA (US)

Died

July 31, 1984 at Long Beach, CA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.