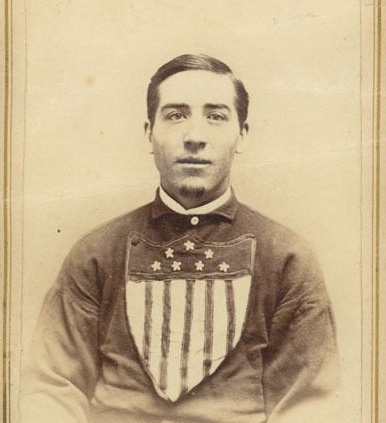

Bill Craver

Bill Craver was known as one of the best catchers of his time and an innovator at that position. He was also known as a gambler and a troublemaker — one of baseball’s early wily characters. His run-ins with fans, opponents, teammates, and umpires were noteworthy, yet the biggest impact made by this early star was his unceremonious exit from baseball, one of the first casualties of a crusade by the fledgling National League of Professional Baseball Clubs to stamp out the vice of gambling before it could take root.

Bill Craver was known as one of the best catchers of his time and an innovator at that position. He was also known as a gambler and a troublemaker — one of baseball’s early wily characters. His run-ins with fans, opponents, teammates, and umpires were noteworthy, yet the biggest impact made by this early star was his unceremonious exit from baseball, one of the first casualties of a crusade by the fledgling National League of Professional Baseball Clubs to stamp out the vice of gambling before it could take root.

Off the cusp of their first major scandal, the owners of baseball wanted to make a statement that would be everlasting. But true to form, the maverick Craver was going to challenge authority, in hope of securing the biggest victory of his career, or to at least saving it and his name and legacy.

William H. “Bill” Craver was born on June 13, 1844, in Troy, New York, the second of five children born to James and Phoebe Hawkins Craver. His father, James, was a carpenter by trade; Phoebe worked at home raising the children. By 1860, Bill was helping the family financially by peddling tin. In 1862, as the Civil War was raging, Craver enlisted in the Union Army as a private in the 23rd Light Artillery. His headstone shows that he also served in Company K, the Heavy Artillery Regiment of New York. Craver eventually mustered out in Buffalo, New York.

After the war, Craver joined his first professional baseball squad, the Lansingburgh Union, later known as the Troy Haymakers, a team originally founded in 1860.1 It was one of the most dominant teams of that time, able to hold its own with the top teams in the league. Craver was an important part of that dominance and received praises for his play at catcher. The New York Daily Herald reported that the rising star had “but few equals as a catcher in New York State.”2

A Buffalo newspaper took the praise even further: “We do not claim too much for him when we say that, in his position, he has no equal in the country. He is conceded to be, by all competent judges, the best man behind the bat now on the field, and in throwing to bases he has scarcely an equal.”3

Henry Chadwick, the early baseball pioneer known as “The Father of Baseball,” referred to Craver as “the great North American catcher,” being “safe, sure and reliable behind the bat” and “a tremendous hitter.”4

To play his position more effectively, Craver became an innovator behind the plate. His efforts did not go unnoticed. One slugger from the 1870s, outfielder Ned Cuthbert, commented on Craver’s style of play. “Craver was known as the patentee of the foul tip. He would stand so close to the bat that often he would catch the ball before the player got a chance to rap it,” said Cuthbert.5

Craver’s style did not come without sacrifice. This was in a time when catchers did not wear gloves or masks. Cuthbert continued, “Craver’s face … looked like a prize-fighter who had been through many a good fight.”6

Future Hall of Famer Cap Anson complimented the catcher further, “There are plenty of backstops today and there have been lots of them in the past, but I don’t believe any one of them was a match for Bill Craver.” Of Craver’s style, Anson stated, “Bill would stand up under the bat and scoop up everything that came along. The star play for a catcher in those days was a foul tip and Craver originated the trick of snapping his fingers. The snap fooled many an umpire into calling a foul and giving Bill a chance to earn thunderous applause.”7

The foul ball was an occasional source of controversy for Craver. In 1867, as the catcher pursued a foul pop behind home plate, a crowd of the “rough element” began to call out and heckle him. Words were exchanged and a confrontation ensued. Craver’s actions brought the ire of the press. A newspaper proclaimed that “by his disgusting action he [Craver] put himself on a level with those that insulted him.”8

Several years later at Cincinnati, Craver was unable to come up with a foul tip, and instead came up with a handful of gravel. Quickly recovering the ball, however, he tried to get the umpire to call the batter out. The official allowed the batter to continue his turn at the plate, incensing both Craver and the Lansingburgh president James McKeon, who called for the club to pack up and leave. The game was declared a winner for the home team.9

In the spring of 1870, Craver had left the confines of Troy and signed a contract with the Chicago White Stockings. “Craver is not one of the ‘revolving’ kind, and there is no doubt of his sticking to his agreement,” stated the Chicago Tribune.10 However, an injury to his hand disabled the catcher for a time.11 Unable to catch, Craver moved to other positions in the field, including shortstop and the outfield.12

By August of that year, however, the agreement was shattered by inappropriate behavior. Craver was expelled by the club “on account of a mixture of personal and financial reasons.” Though he was deemed to have had “no superior in America — perhaps no equal” when it came to his prowess as a catcher, the club’s hand was forced.13

A day later the club released a statement regarding the grievance, noting that Craver had violated his contract in a number of ways, but his most egregious sin was disregard of rule number 13 of the contract: “Gambling of any manner whatever, is prohibited at all times, and no player of the club shall change the games in which he plays or induce others to try to do so.” The catcher had “violated the confidence of the public in said nine” by “having received [money] as … inducement for aiding in winning games.”

Craver was also accused of not acting like a gentleman, not playing when ordered to do so, and seeking “to create strife and confusion in the nine,” among other things. The club moved that Craver be expelled, and his contract made null and void. To take matters further, the club moved to refuse to play any team carrying Craver. The letter was signed by Fred Erby, the team’s secretary.14 The war between the White Stockings and Craver was just beginning.

The following day, August 22, Craver fired back a letter to the editor of the Tribune defending himself against the allegations. He first addressed the accusation that he did not play when ordered to do so. He stated that he “was sick at the time set to play with the Aetnas, on Wednesday, and unable to play.” He informed “Mr. Tom Foley, who told him he would take no hour’s notice” and that Craver was “to put on [his] clothes and play.” Seeing no relief and thinking of the health of the rest of the nine, he “refused to take [his] position.” Furthermore, he denied using bad language on the field of play and smoking. He did admit to drinking liquor on the diamond, just the same as the other players on the team and only when brought to them by team officials.15

With regads to the gambling accusations, Craver took a shot at the author of the Chicago letter, Fred Erby. First, he acknowledged he was guilty of breaking Rule 13. He stated that the instance occurred at Dexter Park when the Forest Citys of Rockford came to play. He “bet Mr. Fred. Erby, then a stockholder, and now Secretary of the club, that the Chicago nine would win.” Craver then claimed the only money received from said game was $10 sent to every player by Mr. Norman T. Gassette “as a reward for having beaten the Rockford club. In three or four instances, during our Eastern trip, Major Phelps, then manager of the club, gave me $10 when the Chicago nine won, and proposed to give the same amount in other instances, but, as the Chicago nine were beaten, the money was not given.” Craver continued, “This is the extent of money received ‘as an inducement for winning games.’”16

The accused was not finished, with his concluding barb sharp and sure. “It strikes me that if the managers of the Chicago nine would talk less about conduct becoming gentlemen and put in a little more practice in that direction a vast improvement will have been made.” He referred to the accusations as being “a tissue of falsehoods and a great array of glittering generalities made to cover a chasm in which there is substantially nothing but sound; a grand crater of jealousy and rivalry between certain parties who have always wrangled, and will always wrangle, for a position to which they are not entitled either by tact or intelligence.”17 Craver was done with Chicago.

Several weeks later, the catcher looked home for his chance to play in a friendlier environment. Several clubs apparently caught wind of this idea, including the Chicagos, who had already refused to play any team using Craver’s services. In early October, the New York Mutuals and Brooklyn Atlantics threatened to follow suit.18 But Craver had signed to play for the Troy Haymakers by the end of the season, this time at second base.19

By season’s end, the White Stockings tried to banish Craver completely from the league. Their attempts at the player’s expulsion were discredited by Henry Chadwick and ignored by the other clubs within the Association.20 With Chicago’s inability to build a valid case against him, Craver played the 1871 season back in Troy. Chicago still threatened the other Association clubs with sanctions and fines, but to no avail. The accused batted .322 in 27 games that season. The team finished in sixth place in the nine-team league. Craver took his turn has manager, garnering a 12-12-1 record in 25 games following Lip Pike’s brief four-game stint as skipper.

Though he was one of the team’s leading hitters and managed them down the stretch, the pastures were not green for Craver in Troy. On his way out and on to Baltimore for the 1872 season, Craver was the recipient of criticism from his former team. Troy was relieved to be rid of Craver, and several other of its “turbulent and disagreeable spirits,” as one critic referred to them. The naysayer continued, “Bill Craver, Lip Pike, Bill Fisher, and Dick Higham would seem to be a trial to any one man, and if [Baltimore executive Nick] Young succeeds in managing them, he deserves something nice in the way of a dividend.”21

Living up to his reputation, Craver, managing and catching for the Canaries, found trouble in late April versus the Mutuals. While running for a score at home plate, Craver kicked the baseball which was in his path, allowing him to score easily. The opponents protested, but the umpire believed Craver’s claim that it was accidental and allowed the run.22

Dirty play aside, Craver led the team as manager to a 27-13 record, while batting .281. He was replaced as skipper of the club toward the end of the season by Everett Mills. The Baltimores finished 35-19, good for second, 7½ games behind Boston. One newspaper lamented, “The Baltimore nine lack both in discipline and in the want of an able Captain.”23 Craver would return to Baltimore for a second season, but not as manager.

The 1873 Canaries finished third, going 34-22. Craver played 22 games behind the plate and 18 in the infield and hit .289. If not for the mid-season expulsion from the club of pitcher Candy Cummings, claimed the Baltimore Sun, the Baltimores may have taken first. “When Cummins (sic) left the club the nine was in the lead.”24

Craver and his fellow Canaries planned to return for the 1874 season, but financial woes struck the club and the owners attempted to fold. Craver was set to make $1,200 that season25 and was now looking to sue the team for missing compensation. Along with John Radcliff, Tom Carey, Scott Hastings, and Tom York, Craver sued the Baltimore club for almost $2,000 for their services. The owners of the squad refused to pay the funds on grounds that the players broke their contracts by “drinking spirituous liquors.”26 The Canaries lasted one more season — without Craver — folding after going 9-38.

Craver had exited Baltimore following the ’73 season, having signed with the Philadelphia Whites. For Craver it was a career year. He was the starting second baseman, leading all at the position in putouts (175) and errors (75), while finishing second in double plays turned (27). At the plate he finished sixth in batting (.343), third in doubles (19), and second in triples (11).

Late in the season, Philadelphia visited one of Craver’s old haunts, Chicago. Following a 7-2 victory over the White Stockings, the star’s baserunning skills were noted. In a surprise, an article in the Chicago Tribune spoke highly of their former player. “Craver, who is fast building up a reputation as one of the most skillful and daring base-runners,” the paper stated, “played nicely, and caused much good humor by his risks to run up the score.” Craver managed two of the team’s seven runs in that game.27 For the season, the Whites finished 29-29 and in fourth place.

Sad to say, the good vibes would not last, for by early September Craver was embroiled in yet another scandal. Umpire Billy McLean stated that before a game versus Chicago he was approached by Philadelphia utilityman John Radcliff asking the official to call the game in favor of the White Stockings, “representing that he and four other members of the nine were peculiarly interested in the result.” Those other four were Craver, first baseman Denny Mack, pitcher Candy Cummings, and catcher Nat Hicks. Team officials voted to acquit the four and expel Radcliff. Their ruling stated, “they do find nothing that would justify us in censuring them, except their loose and careless playing during certain games.”28 Accused and acquitted, Craver was one and done with the Whites.

Staying in Philadelphia, Craver signed with the Centennials for the 1875 season. At the age of 31, he was the oldest player on the squad and served as shortstop and manager. With a mix of veterans and amateurs, the team’s destiny seemed unclear. Reported one newspaper, “The ‘Centennials’ will present a team of mixed quality, containing four full-fledged professionals, the balance of the amateur class. How these latter will work with their more experienced brethren remains to be seen.”29

By mid-May, rumors were swirling of the demise of the Centennials.30 They were one of three teams in Philadelphia and had not won any games at home. After a 2-12 start, the team folded. Craver was batting .277 at the time and led the team with 18 hits.

To recoup losses, the Centennials struck a deal with the Athletics in one of the first recorded “transactions” in baseball history. Craver and pitcher George Bechtel were acquired by the latter for cash considerations — the sum of $1,500 — thus financially aiding the now folded club in exchange for the players’ services.31 The Athletics already featured a young-but-established Cap Anson, along with infielder Ezra Sutton and pitcher Dick McBride. This was not a team of amateurs.

Craver played second and hit .319 with the Athletics, including two home runs, the only homers of his career. One of his most peculiar hits came in the eighth inning of a game versus New Haven in early June. According to the Times, “A singular hit was made by Craver in the eighth inning, the ball being sent way down to left field where it entered the door of a stable and flew in the stall of a horse. The hit was good for three bases really, but this hit let Craver get all around.”32

The Athletics finished the season 53-20, good for second place. By season’s end it was rumored that Craver and several others were looking to return to the club for 1876.33 However, with financial woes besetting his current team, the aging baseballist looked elsewhere the following spring.

With the birth of the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs in February 1876, baseball had been reborn and fashioned into a new product, one with rules that would hopefully retain teams, curb gambling, and prove to be a success at the gates. The following month, Craver signed with the National League’s New York Mutuals and once again found himself playing second and managing.34 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle predicted, “If this team ‘plays for the side,’ and try their best to win in all their games, they will be very close to the leading club by August.”35

Unfortunately, the Mutuals got off to a horrid start, going 3-10 in their first 13 games, including a 28-3 drubbing at the hands of the Hartford Dark Blues in mid-May. Though the team tried to recover, going 7-2 over their next nine games, they fell back into their old ways by losing eight straight and finding themselves 14½ games out of first. The club finished the season 21-35 and in sixth place. Craver batted a lowly .224, by far the worst offensive season of his career. He would not return as manager the following season.

The season was not all bad. On May 13 at the Hartford Ball Club Grounds, Dick Higham hit a scalding line drive to second base which was snared by Craver. The bases were loaded, and the runners had been on the move with the pitch. Craver quickly relayed the ball to first to double up Jack Remsen. Mutuals’ first baseman Joe Start then threw to Craver at second to double up Jack Burdock, thus completing the National League’s first triple play.

In early June versus the Cincinnati Red Stockings, an old specter returned to haunt Craver. Following a game, a “well-known member of the betting fraternity and regular frequenter of the Union Grounds” approached Craver and punched him several times. According to the report, Craver “tamely submitted” to the assault. The attacker was arrested but “neither Craver nor the proprietor of the grounds had any complaint to make.”

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle raised the suspicion that Craver was “either of a craven nature, or that the party who attacked him had some power over him which prevented his making any reprisal.”36 This act may have been odd to some, but to most in the area, the Mutuals had a checkered past with gamblers, including rumors of involvement with the corrupt New York politician, Boss Tweed. Knowing Craver’s history with gamblers as well, the event was not all that surprising.

As September arrived, the Mutuals prepared for a trip out west. However, citing financial ills, team owner William Cammeyer refused to allow the team to travel. Both Chicago and St. Louis offered money to assist, but Cammeyer would not have it. Because the team had reneged on its duty to make the road trip and complete the schedule, the Mutuals, along with the Philadelphia Athletics for a similar reason, were expelled from the league following the season.37 Once again Craver had to pack up and sign with another franchise. This time he looked west to the Louisville Grays.

Louisville was looking forward to a competitive season after new roster additions, including Craver, but the team knew to keep a watchful eye on their new star. Team vice president Charles Chase stated of Craver that “his reputation is not first class, but … we have taken him with our eyes open, and we are willing to abide the result.” Chase continued, “when [Craver] comes with us he will have to play or quit, and he fully understands this.”38

Craver played shortstop for the squad. The veteran batted .265 for the season and received praise for his play. “Speaking of steady, reliable work,” stated the Chicago Tribune, “[third baseman Bill] Hague and Craver are just about as clever as the majority of them. They make errors occasionally, but a set of nine as cool-headed as they are would prove a paying investment to someone anxious to run a nine.”39

By mid-May Craver was serving as assistant captain to teammate George Hall.40 The Grays finished 35-25 and in second place, seven games behind Boston. But where Craver set foot, trouble followed.

At the end of October, the stockholders of the Louisville nine announced the expulsion of four players who “were knaves, who sold out games.” The vote was unanimous. Bill Craver, George Hall (captain/outfielder/leading hitter), Jim Devlin (pitcher), and Al Nichols (backup infielder) were now unemployed and would soon face the wrath of league leadership.41 They had been suspected all season. Messages had been sent via telegraph to the guilty from Brooklyn, Chicago, and New York.

Soon, Nichols was held back from a road trip to St. Louis by Charles Chase. The vice president confronted the infielder about the messages, demanding to see them. According to one news article, “Several messages were thus obtained, and they were found to relate blindly to the selling of the game about to be played.” A pool seller (later identified as “McCloud”) in Brooklyn was named on a message looking to see “if a previous agreement was to be kept.”

As the investigation unfolded, George Hall confessed his guilt; Jim Devlin soon followed. 42 Both implicated themselves and Al Nichols. Though Craver was also mentioned by Devlin and Orator Shafer in testimonies, nothing was directly attached to him.

But the quality of his play and management of the players on the field helped lead some to believe he was crooked. His teammates stated of Craver “that he was the direct cause of most of the errors they made, he having purposely ‘rattled’ them.”43 Craver refused to release the telegraph messages and made no confession.44

League president and Chicago White Stockings executive William Hulbert had made the end of gambling a top priority, and now, two years into the league’s existence, a test of his sincerity to its abolition was at hand. Just over a decade before and at the tail end of the War Between the States, New York Mutuals’ catcher William Wansley and several teammates were banished from baseball for conspiring with gambler Kane McLaughlin to throw a game against the Brooklyn Eckfords. But they were allowed to return.45

At the league convention in December, the directors voted to expel for good the “Louisville four” from the National League for life, thus upholding the league constitution. The National League had faced its first test versus gamblers, and baseball won. In later years, Charley “Pop” Snyder, who served as Devlin’s catcher on the Louisville squad, claimed the players sold out the team for a mere $1,000, split between the four.46

In July 1878, it was reported that Craver had found grace from the International Association — the IA felt he had been dealt with unjustly by Louisville — which allowed him to play and manage the new Troy Haymakers club.47 Troy was not allowed to face any National League clubs. By 1879, Craver owned a pool hall48 and continued playing in the IA.49 But the disgraced star was not giving up hope of a return to the big league. Craver made several attempts in the intervening years at reinstatement, visiting each off-season’s owners meeting. In 1878 the owners refused his request for reinstatement “point-blank.”50 Craver’s request was denied once again the following year.51

His final attempt came in 1880. This time, baseball’s board of directors put a stop to any future attempts. The League stated, “Repeated applications have been made by or on behalf of George Hall, W. H. Craver, and A. H. Nichols to this board … for the removal of their disabilities resulting from their expulsion from the League for dishonest ball-playing. Resolved, that notice is hereby served on the persons … that the board of directors of this League will never remit the penalties inflicted on such persons nor will they hereafter entertain any appeal from them or in their behalf.”52

Unlike Wansley and company from a decade before, Craver and his expelled Louisville teammates were not allowed to return. The former star married his wife Catherine in 1882 and later joined the Troy police force. He died in Troy on June 17, 1901, and he was buried in Oakwood Cemetery with his family. He was 57 and had suffered heart disease. His wife Catherine followed him in death several weeks later. No children were born to the couple.

Almost 40 years before the demise of the Chicago Black Sox and 110 years before the banishment of Pete Rose, Craver and associates had tasted the ire of the owners and their intolerance of gambling. Though Craver was only alleged to have been involved in the Louisville scheme, his history of transgressions and his added stubbornness in refusing to turn over communications or admit any sort of wrongdoing helped to contribute to the label of guilt.

Bill Craver, a former star catcher, manager, and baseball innovator just hoped for forgiveness and a return to the game he loved; however, the door was slammed shut. Only time will tell if Craver and others like him, including Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson, will get their opportunity at redemption and a possible shot at the Hall of Fame. In the meantime, their tales serve as reminders that, no matter how great you might be, there is no betting on baseball.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

In addition to the sources sited within the bibliography, the author consulted the Bill Craver player file and questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball-Almanac.com, Ancestry.com, and Newspapers.com.

Notes

1 Bill Passanno, “Troy’s baseball legacy: A bunch of hicks,” Record News (Troy, New York), August 27, 2001. troyrecord.com/article/TR/20101110/NEWS/311109973, accessed July 26, 2018.

2 “The National Game: Base Ball Notes,” New York Herald, June 24, 1868: 4.

3 “Base Ball,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, August 7, 1868: 4.

4 Daniel E. Ginsburg, The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995):, 11.

5 “Cuthbert’s Reminiscences: The Crack Left-Fielder Reviews the Prominent Players of His Day,” Chicago Tribune, August 8, 1886: 14.

6 “Cuthbert’s Reminiscences.”

7 “Base Ball Notes,” The Brooklyn Eagle, June 6, 1892: 1.

8 “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” The Brooklyn Eagle, September 27, 1867: 2.

9 “The Base Ball Match at Cincinnati,” Wheeling Intelligencer (West Virginia), August 28, 1869: 4.

10 “Base Ball Matters,” Chicago Tribune, April 2, 1870: 4.

11 “Telegraph! Midnight Report: From Chicago,” Leavenworth Times (Kansas), June 17, 1870: 1.

12 “The National Game,” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1870: 4.

13 “The Sporting World,” Chicago Tribune, August 20, 1870: 3.

14 “The Sporting World,” Chicago Tribune, August 21, 1870: 3.

15 “The National Game,” Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1870: 4.

16 “The National Game,” Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1870: 4.

17 “The National Game,” Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1870: 4.

18 “The Sporting World: General Items,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1870: 4.

19 “The Sporting World: Red Stockings vs Haymakers,” Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1870: 4

20 Ginsburg, 12.

21 Bobbles, “The National Game: Jimmy Wood’s Troy Club — Interesting Gossip,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1872: 8.

22 “The Base Ball Season: Baltimore vs New York,” Baltimore Sun, April 23, 1872: 1.

23 “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 8, 1872: 3.

24 “Closing of the Base Ball Season — Baltimore Third in the List,” Baltimore Sun, November 7, 1873: 4.

25 “Foreign: Spiritualists,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 24, 1873: 1.

26 “Local Matters: Base Ball Men in Court,” Baltimore Sun, June 11, 1874: 4.

27 “Base Ball: The White Stockings Defeated by the Philadelphias,” Chicago Tribune, September 4, 1874: 8.

28 “Base Ball: An Adjourned Meeting of the Philadelphia Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1874: 2.

29 “The Professional Arena: A Review of the Coming Base-Ball Season,” Philadelphia Times, April 3, 1875: 3.

30 “Gossip of the Game,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1875: 14.

31 “Matters and Things,” Chicago Tribune, October 10, 1875: 12.

32 “The Ball-Field: The Athletic Defeats the New Haven in a Good Batting Game,” Philadelphia Times, June 5, 1875: 4.

33 “Minor Notes,” Times-Democrat (New Orleans), September 12, 1875: 10.

34 “Games and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1876: 12.

35 “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 6, 1876: 2.

36 “Sports and Pastimes: Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 7, 1876: 2.

37 Michael Haupert, “William Hulbert and the Birth of the National League,” https://sabr.org/journal/article/william-hulbert-and-birth-national-league , accessed August 8, 2018.

38 “Pastimes: Prospects in the South,” Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1877: 7.

39 “General Notes,” Courier-Journal (Louisville), May 30, 1877: 4.

40 “Amateur and General,” Chicago Tribune, May 20, 1877: 7.

41 “Ledger Lines,” Public Ledger (Memphis, Tennessee), October 31, 1877: 3.

42 “Dishonest Ball Players,” The Union Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), November 15, 1877: 4.

43 “Sporting: Further Relating to Louisville’s Base-Ball Crooks,” Chicago Tribune, November 4, 1877: 7.

44 “Dishonest Ball Players,” The Union Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), November 15, 1877: 4.

45 Rob Neyer, “Two distinct periods of gambling,” ESPN.com, January 7, 2004. espn.com/mlb/columns/story?columnist=neyer_rob&id=1702483, accessed July 5, 2022.

46 “Hurlbert’s Role: He Saved Baseball from the Gamblers/Charley Snyder Talks,” Buffalo Courier, October 3, 1898: 3.

47 “Base Ball,” Buffalo Morning Express, July 9, 1878: 4.

48 “Troy City Notes,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 13, 1879: 2.

49 “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 19, 1879: 3.

50 “Base-Ball,” Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1878: 5.

51 “Base Ball: Stormy Meeting of the League,” Boston Globe, December 4, 1879: 1.

52 “Base Ball: Meeting of the Directors of the National Base Ball League,” Boston Post, December 9, 1880: 2.

Full Name

William H. Craver

Born

June , 1844 at Troy, NY (US)

Died

June 17, 1901 at Troy, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.