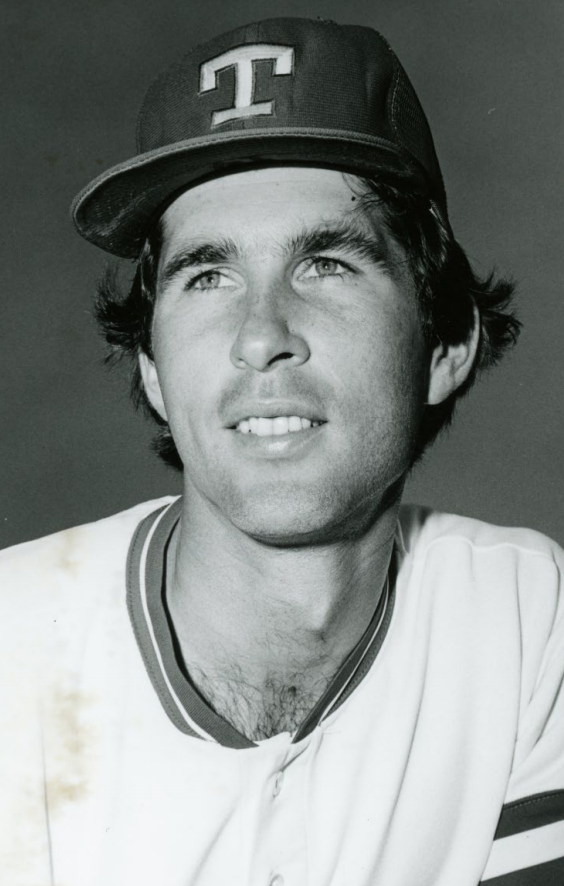

Bill Fahey

When the Washington Senators arrived in Pompano Beach, Florida, for spring training in 1971, manager Ted Williams couldn’t help but gush over his first overall pick in the January draft a year earlier. “That kid has major leaguer written all over him,” the Hall of Famer said of 20-year-old Detroit native William Roger “Bill” Fahey. “He can catch in the big leagues right now. But he’ll need more hitting experience in the minors.” Then Williams doubled down on his prediction for the future of the Senators catcher. “He’ll be the American League All-Star catcher in 1975.”1

When the Washington Senators arrived in Pompano Beach, Florida, for spring training in 1971, manager Ted Williams couldn’t help but gush over his first overall pick in the January draft a year earlier. “That kid has major leaguer written all over him,” the Hall of Famer said of 20-year-old Detroit native William Roger “Bill” Fahey. “He can catch in the big leagues right now. But he’ll need more hitting experience in the minors.” Then Williams doubled down on his prediction for the future of the Senators catcher. “He’ll be the American League All-Star catcher in 1975.”1

Bill Fahey was born on June 14, 1950, and grew up a fan of his hometown Detroit Tigers, idolizing the likes of Al Kaline and Bill Freehan.2 Like most kids in the ’50s, Fahey played Little League baseball before moving through the ranks to the Connie Mack level, for players of high-school age, the highest youth baseball classification in Michigan. Playing Connie Mack ball, Fahey showed the flashes of talent that led to his status as a five-sport high-school athlete at Union High in Redford, Michigan, a few miles northwest of downtown Detroit. At Union High, Fahey played both offense and defense in football (quarterback and linebacker), was co-captain of the basketball team, wrestled in the heavyweight division, was a member of the golf team, and played baseball.3 Regardless of the sport, Fahey’s 6-foot, 200-pound frame was an imposing sight, and when opponents realized he had speed other kids his size lacked, he became the type of player game plans are built to avoid.

While Fahey was successful at all sports, he concentrated on baseball, playing at the All-American Amateur Association level after the Connie Mack league and very nearly leading his team to a regional championship in 1969.4 By that point, Fahey was already a hot commodity in professional scouting circles, catching batting practice for Detroit and having been Baltimore’s 13th-round selection in the 1968 amateur draft.

“I might catch one ball during batting practice because they hit everything (in batting practice),” Fahey later said of his time behind the plate at Tiger Stadium. “The coach is just throwing it in there. But, heck, I was just a kid. My heart was pumping out of my chest.”5

Like many players drafted in the lower rounds straight out of high school, Fahey rolled the dice, passed on the Orioles’ offer, and enrolled in the University of Detroit, where he played the 1969 collegiate season. In the fall of 1969, he transferred to St. Clair Junior College.6 St. Clair, unlike the University of Detroit, was a two-year institution, and under the rules of the baseball draft, the transfer made Fahey eligible for the secondary draft in January 1970.7 The Washington Senators chose him with the first overall selection in the draft. After eight dreadful seasons in the nation’s capital, Ted Williams’s Senators were coming off their first winning season but felt slowed by the catching staff of Paul Casanova and Jim French. Fahey’s signing bonus has been reported in different publications over the years as ranging from “an undisclosed substantial bonus”8 to $40,000.9 Based on Williams’s rave reviews several weeks later, Fahey looked to be on the fast track to the big leagues.

The Sporting News commented on Fahey’s selection: “Senators farm department feels they plucked a plum in the special phase of the free agent draft in the selection of Bill Fahey, 19-year-old catcher from suburban Detroit.” The publication said Fahey would have been the top pick of any number of teams in the draft and opined that the Senators “apparently drafted a phenom.”10 In spite of the rave reviews of the media and Ted Williams, Fahey and most of the Senators’ other “can’t miss” rookies were assigned to Class-A ball. Fahey spent 1970 with the Burlington (North Carolina) Senators of the Carolina League.

While Fahey didn’t tear up the Carolina League in his first professional season, he did catch 118 games for the third-place Senators, batting .244 with 3 home runs and 36 RBIs. But as Ted Williams’s comments the following February indicated, Fahey wasn’t drafted for his bat but for his defense. He posted a .988 fielding percentage, placing him second among everyday catchers in the eight-team circuit, and he led the league in putouts and chances accepted.11 With one professional season under his belt, the prognosticators began to weigh in on Fahey’s future, with one writer offering the comments, “…as much raw talent as any catcher in Senators’ system,”12 “…best of the crop,”13 and “…likely to be Senators’ everyday catcher in a couple of years.”14

Fahey made the jump to the Double-A Eastern League in 1971, catching 99 games for the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Senators and posting a .990 fielding percentage. His offensive output increased dramatically: His batting average improved to .286, and he showed flashes of the speed that had made him such a high-school standout, stealing 13 bases without being thrown out. No other Eastern League catcher even attempted to steal more than seven bases. After being named to the Eastern League All-Star team15 late in the season, Fahey was briefly promoted to Triple-A Denver, where he got four hits in four games and fielded to perfection. Before the season ended, Ted Williams called his catcher of the future to Washington for his first major-league appearance. His two appearances, against the Red Sox and Yankees in late September, yielded no hits in eight plate appearances and even a rare error in the field. That short would be his only one in a Senators uniform. During the offseason the franchise relocated to Arlington, Texas, and prepared to begin play in 1972 as the Texas Rangers.

Team owner Bob Short, notorious in Washington for promoting young players to draw fan interest,16 continued the pattern in Texas, often rushing players to the majors before they were ready. Fahey was among the rush jobs in 1972.17 He spent the first half of the season with Denver, continuing his stellar defensive play. The Rangers called Fahey up in late July, and he stayed with them the remainder of the season,18 playing in 39 games. Fahey’s defensive prowess shined brightly with a fielding percentage of .992, and he threw out 44 percent of would-be basestealers, five points above the league average. Offensively, Fahey was dreadful, batting just .168 with three extra-base hits and 10 RBIs in 119 at-bats. His first major-league hit and RBI came off California Angels pitcher Clyde Wright as a pinch-hitter in the eighth inning of a 3-2 Texas loss on July 28. On September 4, Fahey slammed his first home run, a two-run shot off Kansas City’s Ted Abernathy in front of 3,710 fans at Arlington Stadium. Despite Fahey’s lack of offensive punch, statistically he outplayed Hal King and Ken Suarez, who also auditioned for the new label “Texas’s catcher of the future.”

In 1973 new Rangers manager Whitey Herzog elected to go with experience at catcher, keeping Dick Billings and Suarez on the roster. Fahey was assigned to Spokane of the Pacific Coast League and remained in Triple A all season. He was the starting catcher for the PCL West All-Star team, and had two RBIs in his squad’s 9-6 win. Fahey lived up to Herzog’s praise for his ability to block the plate, a skill he’d shown off at Pittsfield in 1971 when the burly catcher held onto the ball in a violent home-plate collision.19 On August 9, 1973, Fahey again blocked the plate, only this time the result became a turning point in his career.

With the Hawaii Islanders visiting Spokane, Hawaii outfielder Chris Coletta sped toward home on a single to the outfield. As Fahey reached for the approaching throw, Coletta’s knee struck him in the side of his torso. This time Fahey didn’t hold onto the ball for the out, and he didn’t stand up. Instead, he was carried from the field to the hospital, where he remained for 10 days. With five broken ribs and a punctured lung, the collision led to a string of injuries that plagued Fahey for three seasons. Just two weeks later, after Spokane swept Tucson for the PCL championship, Indians fans named the injured Fahey the team’s most valuable player.20

Despite the Rangers trainers and team doctors questioning whether Fahey would be ready for spring training, in early January the team declared him fully healed. No doubt Fahey was eager to get back on the field. Whitey Herzog hadn’t lasted the season as the Texas manager before being replaced by Billy Martin. With a new skipper, Fahey expected a better shot at making the Rangers roster. He headed for camp as one of seven catchers, a group that included Jim Sundberg, a second-year professional who had burst onto the scene with an outstanding 1973 season at Double-A Pittsfield. It didn’t take long for Fahey to lose traction in his bid for a roster spot. On the first day of spring training, a thrown ball hit him directly in the face, breaking his nose, and because of complications, landing him in the hospital for another extended stay.21 While the remaining six catchers auditioned for Billy Martin, Fahey lost valuable playing time, and no doubt Martin began to wonder if the player previously called the catcher of the future wasn’t injury-prone. When Sundberg grabbed the starting catcher’s slot and Duke Sims beat out the contenders for the backup position, once again Fahey opened the season in Spokane. He remained with the Indians for all but six games.

Fahey had another excellent season at the Triple-A level, but talk of him as the future catcher of the Texas Rangers faded. Jim Sundberg developed more quickly than Fahey, matched his ability defensively, and added more to the lineup as a hitter. In November 1974, The Sporting News noted that Fahey, “once rated as the Rangers’ future catcher, must be considered in trade talks.”22 Two weeks later, TSN called him “expendable” due to Sundberg’s development, although it said he might hang on as the Rangers’ backup catcher.23 That is exactly what Bill Fahey did.

With most teams, Fahey’s status as backup catcher would have earned him a decent amount of playing time. Unfortunately for him, the 1975 Rangers had a catching machine in Sundberg. The budding star started 148 games, with the remainder split between Fahey and Ron Pruitt. Fahey played in 21 games with only 39 plate appearances, although he did bat .297, the best batting average of his professional career. He might have gained more playing time if not for another injury, a broken hand suffered from a foul tip that landed him on the 21-day disabled list.24 For the third time in three seasons, Fahey lost significant playing time because of an injury. He also endured another managerial change as Robert Short fired Billy Martin midway through the season in spite of the Rangers’ finishing just five games behind Oakland in the American League West and drawing over a million fans in 1974.

In 1976, Billy Martin’s replacement, Frank Lucchesi, chose Fahey as the Rangers’ regular backup catcher. He played in 38 games, his most in a major-league season to date, and batted .250 in 94 plate appearances. Again, he was stellar in the field with a .993 fielding percentage while throwing out a respectable 32 percent of runners attempting to steal a base. Fahey maintained his position and posted similar numbers in 1977, but when 1978 arrived, he once again found himself playing Triple-A ball, this time with Tucson in the PCL. John Ellis, a former Yankee and a three-year starting catcher for the Cleveland Indians, beat Fahey out as Sundberg’s backup. For Fahey, the writing was on the wall. In December 1978, he was traded along with Mike Hargrove and Kurt Bevacqua to San Diego in exchange for Oscar Gamble and Dave Roberts. Many considered Fahey the player “thrown in” by the Rangers to make the trade for Gamble and Roberts equal.25 At the time, an argument could definitely be made that Texas needed to rid itself of Fahey to clear the way to develop new catching prospects.

For San Diego, Gene Tenace held down the catcher’s position, and veteran Fred Kendall, in his second stint with the team, was a serviceable backup. But when speaking of Fahey, San Diego manager Roger Craig commented, “I like his attitude. He has great desire. … Maybe all he’s needed was to be healthy and have a chance to play every day.”26 Of course, Craig also pointed out how much he liked the way his new catcher blocked the plate, a primary source of Fahey’s injuries. When Gene Tenace moved to first base in August of 1979, Craig offered Fahey his first chance to be an everyday catcher. Fahey responded to the challenge, batting .287 in 73 games, with a career-high 3 home runs and 19 RBIs. He maintained a.994 fielding percentage and threw out 36 percent of would-be basestealers.

In 1980, although his batting average and fielding percentage fell, Fahey had finally become a somewhat regular player, appearing in 93 games for the Padres. Late in the season, teams like the Red Sox showed interest in obtaining Fahey for a pennant run, but it wasn’t until March 1981 that the Padres turned their backup catcher loose. For Fahey, his dream came true with the change in scenery.27

In December 1980, San Diego sent Gene Tenace, Rollie Fingers, Bob Shirley, and a player to be named to St. Louis in return for seven players including backstops Terry Kennedy and veteran Steve Swisher. Two weeks before Opening Day, the Padres sold Fahey to Detroit for $90,000 cash. After a decade bouncing between the minors, Texas, and San Diego, Fahey headed home to where he’d caught batting practice his senior year in high school. Now he would be a backup to Lance Parrish, the Tigers’ regular catcher.

From 1981 through most of 1983, Fahey played sparingly, as utilityman John Wockenfuss caught a good share of the games Parrish sat out. By 1982, Roger Craig had arrived in Detroit as the Tigers’ pitching coach and began working with Fahey. On August 24, Craig and Fahey were involved in what may have been the most notorious moment of Fahey’s career.

Craig called Fahey that morning and told him he’d be playing in Oakland in place of Parrish, who had flown home for the birth of his child. The Athletics, managed by Fahey’s old Texas manager Billy Martin, were simply playing out the string in the midst of a horrible season. The A’s Rickey Henderson was pursuing Lou Brock’s single-season record of 118 stolen bases. Henderson entered the August 24 game needing just three to tie Brock’s record, and after getting on base early and stealing second and third off Fahey’s normally powerful arm, only one stolen base remained for the tie. Henderson had a chance to break the record in front of the home crowd.

Henderson was on deck for the bottom of the eighth inning, when Fred Stanley drew a walk. Stanley, who in 17 professional seasons stole only 48 bases and only 11 of those at the major-league level, was what baseball coaches often call a “base clogger.” When Rickey Henderson hit what he called a “seed” to left field, Stanley hadn’t touched second before the ball was back in the infield.28 So, Henderson stood on first, blocked from even attempting to tie Lou Brock’s record by one of the Tigers’ slowest baserunners. When Stanley received the steal sign from third-base coach Clete Boyer, he knew his odds were slim. Indeed they were, as Stanley was caught in a rundown that Detroit third baseman Enos Cabell considered merely an attempt to open a base for Henderson and he didn’t even run to tag Stanley out.

Fahey said Craig came to the mound and told pitcher Jerry Ujdur to toss over to first base three times, then throw Fahey a pitchout. All went as planned, and on the pitchout Henderson took off like lightning for second base. It took everything Fahey had in his arm to make it a close play even on a pitchout, but when Henderson arrived at second base in a head-first slide, umpire Durwood Merrill, a native of Hooks, Texas, emphatically called him out. Bedlam ensued. Before it was over, Billy Martin, Oakland coach Charlie Metro, third baseman Wayne Gross, and Dwayne Murphy were all tossed from the game. Henderson claimed Merrill told him that if he was to break Lou Brock’s record, he’d have to earn it. Merrill denied making the comment. In any case, as C.W. Nevius wrote, “Henderson tied and broke the record in two games in Milwaukee, and hardly anyone remembers … the catcher. …”29 There’s no telling how many remember Bill Fahey’s role in preventing Henderson from granting the home fans a little pleasure in an otherwise forgettable Oakland season.

Fahey began the 1983 season in Detroit, but with 1980 11th-round draft choice Dwight Lowry set for his major-league debut soon after the All-Star break, the Tigers released Fahey on August 5. After 11 major-league seasons and just 383 games played, the one-time catcher of the future for the Washington Senators and Texas Rangers retired as a player just a season before his hometown Tigers rolled through the American League on the way to a World Series title.

Fahey did not completely cut ties with Detroit. In 1984 he managed the Tigers’ Lakeland team in the Class-A Florida State League. Lakeland’s .319 winning percentage fell quite a bit short of the parent club’s success. It was the last team Fahey managed.

In 1985, Fahey remained with the Detroit organization, serving as an aide to pitching coach Roger Craig. A year later, when Craig was named manager of the San Francisco Giants, he took Fahey along, eventually making him third-base coach. The move bred success for everyone involved, and in 1989, after nearly 20 years in baseball, Fahey got his first taste of the postseason and the World Series when San Francisco faced off against Oakland in what has become known as the Loma Prieta Earthquake Series. Oakland swept the Giants in a four-game Series that took 14 days to complete.

In 1991, while still coaching with Roger Craig, Fahey decided it was time he returned to the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where he and his wife, the former Carla Matthews, raised their sons, Scott and Brandon. Fahey believed that with the Rangers having parted ways with manager Bobby Valentine, coaching slots would be open on the club. He asked Craig for permission to speak with the Rangers, a request to which Craig responded by firing Fahey with three days left in the season.30

Fahey did return home, but no position with the Rangers was in the offing. Eventually, Texas offered a minor-league position that Fahey turned down. Other offers came from Cleveland, the White Sox, and the Mets, the most tempting an offer to manage the Mets’ Triple-A team. Fahey turned down all the offers, having found coaching Little League and Duncanville High School totally satisfying as he watched his sons grow up.31 He also served many years in leadership positions with the Duncanville Baseball Booster Club. In 2015, the Duncanville Independent School District inducted Fahey into its Hall of Honor.32

Scott, Bill and Carla’s oldest son, graduated from Duncanville High in 1997 and played four years of college baseball before returning to his high-school alma mater as a teacher and head baseball coach.33 Brandon, two years younger than Scott, also graduated from Duncanville and was drafted in the 17th round by San Diego. Like his father, Brandon passed on signing a contract, instead attending Grayson Community College in North Texas. A season later Baltimore, the team that had chosen his father over 30 years earlier, drafted him in the 32nd round. Again, Brandon Fahey passed up the opportunity to turn professional and transferred to the University of Texas, where he played for the 2002 College World Series champion Longhorns. Baltimore again chose him in the 12th round. This time Brandon signed and made his debut with the Orioles in 2006. After three seasons bouncing between Triple A and the Orioles, Brandon retired from baseball.

Looking back on his career and what might have been, Bill Fahey took it all in stride. He even gloated a little. After all, he said, he proved that Ted Williams, among the greatest baseball players ever to take the field, didn’t know as much about baseball as he thought he did.

“I proved him wrong,” Fahey said. “Williams said I’d be an All-Star catcher. I proved him wrong.”34

This biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

All statistical information, transactions, seasons various teammates played, and comparisons of statistical data are based on information from Baseball-Reference.com. The author thanks Paul Geisler for supplying a number of sources used in this article.

Notes

1 “Almost Skipper Fahey Picked for Stardom,” Port Huron Times Herald, February 19, 1971.

2 Paul Post, “Fahey’s Ultimate Dream Was Playing for Hometown Team,” Sports Collectors Digest, October 13, 1990.

3 Merrell Whittlesey, “Nats’ Coleman Second Half Bearcat,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1970.

4 “Redford Whipped in Final, 12-9,” Detroit Free Press, August 19, 1969.

5 Paul Post.

6 Bill Fahey player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

7 Jeff Brazier, “The Truth About Junior College Baseball,” baseballcoaches.org, accessed, February 7, 2018.

8 “Fahey Is Signed by Senators,” Port Huron Times Herald, February 17, 1970.

9 “Almost Skipper,” February 19, 1971.

10 Merrell Whittlesey, “Nats’ Coleman.”

11 Bill Fahey player file.

12 Merrell Whittlesey, “Southworth Sleeper on Nat Hill List,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1971.

13 Ibid.

14 Merrell Whittlesey, “Will Nats Prima Donnas Ruffle Ted?” The Sporting News, February 27, 1971.

15 Bill Fahey player file.

16 Merrell Whittlesey, “Will Nats.” February 27, 1971.

17 Merrell Whittlesey, “Lefty Starter Tops Nat Shopping List,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1971.

18 “Tigers Drop 3-1 Game to Lowly Texas Rangers,” Sault Saint Marie Evening News, July 24, 1972.

19 “Eastern League,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1971.

20 “Fahey Recuperates From Injuries to Ribs, Lung,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1973. See also “Coast Toasties,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1973.

21 “Ranger Ramblings,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1974.

22 Merle Heryford, “Rangers Put Two Infielders on Trade Saddles,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1974.

23 Jim Hawkins, “Tigers Willing to Gamble in Their Quest for a Catcher,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1974.

24 Randy Galloway, “Gaylord Reduced to Sad Serf Role as Ranger,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1975.

25 Phil Collier, “Throw-In Fahey Now Padre Prize,” San Diego Union, September 15, 1979.

26 Ibid.

27 Paul Post.

28C.W. Nevius, “Return of the Okey Dokey,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 22, 1990.

29 Ibid.

30 Paul Post.

31 Ibid.

32 Duncanville Independent School District, “Duncanville Athletics Hall of Honor.” duncanvilleisd.org/Page/254, accessed, February 13, 2018.

33 Ibid.

34 Paul Post.

Full Name

William Roger Fahey

Born

June 14, 1950 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.