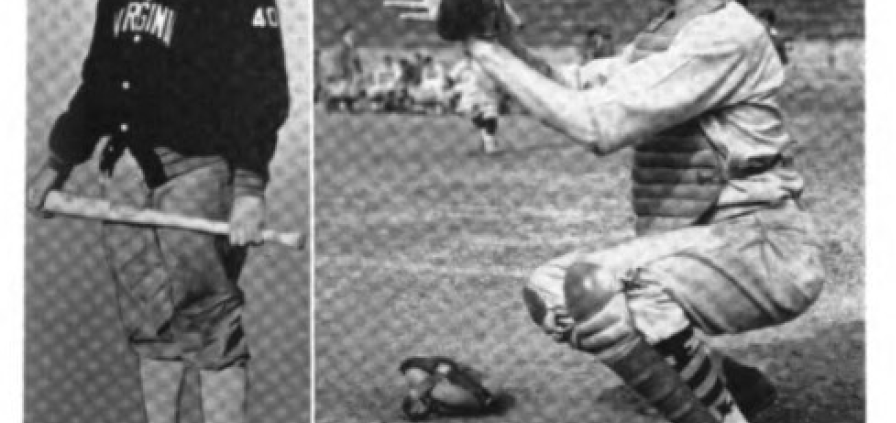

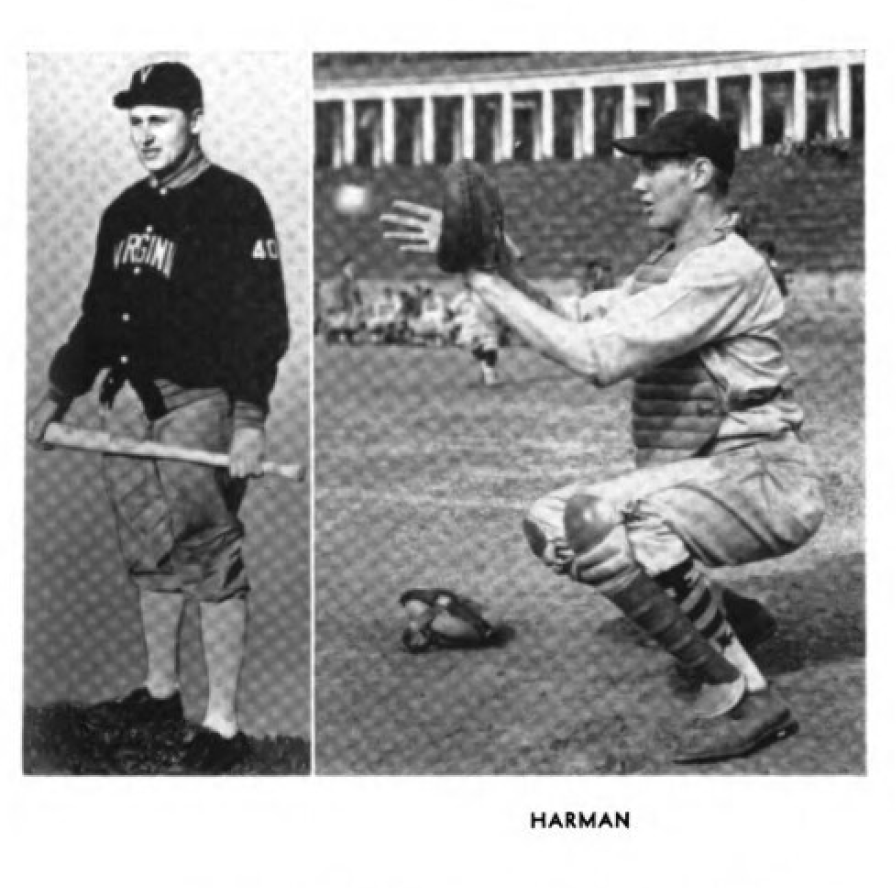

Bill Harman

Bill Harman was a shy country boy who became a leader. He was a star basketball and baseball player at the University of Virginia. As the basketball team’s captain, he led the Cavaliers into the 1941 National Invitational Tournament. And then he played one summer for the Philadelphia Phillies, collecting exactly one base hit. He was a broad-shouldered, 6-foot-4 catcher, who could also pitch. He did the dirty work, cleaning up missed shots underneath the basket and playing one of baseball’s most grueling positions, catcher. He was a leader, captain of both collegiate teams, and student body president. Regularly referred to as “cool under pressure,” he was tested in 1945 as a Marine crewman at the Battle of Okinawa.

Bill Harman was a shy country boy who became a leader. He was a star basketball and baseball player at the University of Virginia. As the basketball team’s captain, he led the Cavaliers into the 1941 National Invitational Tournament. And then he played one summer for the Philadelphia Phillies, collecting exactly one base hit. He was a broad-shouldered, 6-foot-4 catcher, who could also pitch. He did the dirty work, cleaning up missed shots underneath the basket and playing one of baseball’s most grueling positions, catcher. He was a leader, captain of both collegiate teams, and student body president. Regularly referred to as “cool under pressure,” he was tested in 1945 as a Marine crewman at the Battle of Okinawa.

William Bell Harman achieved a lot as the second of four children born to Fred and Margaret (Bell) Harman on January 2, 1919, in Bridgewater, in rural Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. His brother, Fred Jr., was born a year earlier and his sister Virginia followed two years later. Sister Anne was born just before the 1930 census. Fred and Margaret, in their mid-20s when Bill was born, were farmers, living on the farm of Margaret’s parents, Samuel and Sallie Bell, in North River, Virginia.

By 1930 Fred and Margaret and their four children were living with their mother-in-law. Fred owned a farm and they were one of the few families in the area with a radio.1 By 1940, it was college-aged Bill, his parents, and Anne on the farm. Bridgewater is located on a bend of the North River and is susceptible to floods. Fewer than 1,000 people lived in the town during Bill’s youth.

“Virginia farmers tended to fare better than farmers elsewhere, largely because of the prevalence of truck and dairy farming and the continued popularity of tobacco. Nonetheless, drought and the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s hit Virginia farmers especially hard. It would take another world war to help them recover.”2 The Harman farm was likely one of the fortunate ones, being able to send a son to boarding school and having some of life’s luxuries.

In the 1930s, the State of Virginia was sending more children to school from the country to the city. And Bill, it seems, had a thirst for knowledge. Before Bill’s arrival at Episcopal High in Alexandria, the school had 220 students.3 On his departure the the school was one of the five private schools in the state to have “outstanding records in college deans’ offices.”4

For most farmers, “money for necessities was scarce—for luxuries nonexistent,”5 so the fact that Bill’s family was able to send a son to a boarding school says the family likely produced products that for “poverty-stricken people (they) could not do without, such as food, clothing, and cigarettes.”6

Bill attended Episcopal High from 1935 to 1937 and was a member of the basketball and baseball teams. Annual tuition for the boarding school was $850 and there was a limited amount of scholarships. Bill did not receive one. Students attended from all over – New York, New Jersey, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi, and as far away as Texas, Ohio, and even Ireland. The Harman farm was about 150 miles away.

Offdays consisted of Sundays and Mondays with many of the boys venturing into the District of Columbia by train. The boys would hold “hops” with local girls schools. The curriculum was rigorous as students also took Latin, Greek, and of course, religion.

Harman attained a leadership position at the school, serving as “monitor,” an extremely high honor for students. For two years running, he was voted the school’s best basketball player, but also the “most bashful.” The yearbooks regularly said he was “cool under pressure.”

His first year in 1935 the basketball team had its “most successful season in a decade,” going 10-3. In the rivalry game against Woodbury High the newcomer, Harman, along with A.J. Wilson, led the come-from-behind victory for the first win in the series. The team’s “dark horse” averaged 10-12 points per game. The Whispers Yearbook noted it was “unusual for a new boy to make a letter” but that didn’t faze him. He was a “large boy with a few odd characteristics that made him noticeable.”7 In baseball, he was a “country boy,” who made good as a dependable catcher on a young team that won two games.

The 1936 basketball team was built around Harman and another boy. Harman was the team’s captain and was noted in the yearbook as “tall, rangy and smooth” with a “coolness under fire.” He achieved honorable mention all-state honors. Late in the year of a .500 season, Harman hit the game-winning jumper with 15 seconds left after pouring in 16 points two games prior. Harman was one of only four returning players on the 1936 baseball team. He split time with another player at catcher, but when he hit cleanup the Whispers Yearbook wrote he “broke many a pitcher’s heart … (and was) a terror to opposing runners.” He regularly had at least one hit in a game.

The 1937 team featured seven boys over 6 feet; Harman was the “sparkplug” who led them one win shy of the state championship. (A team outbreak of the mumps interrupted their season.) Harman was again one of “outstanding hitters” on the team, which finished just over .500.8

After high school, Harman went on to the University of Virginia, where he played for the freshman basketball and baseball teams, along with another talented freshman, Billy McCann. During their three years at Virginia, the Cavaliers went 49-16 on the hardwood, 28-1 at home. Rules at the time put McCann and Harman on the freshmen teams. The freshman basketball team went 9-3 and outscored opponents 440-290; Harman and McCann were regularly the leading scorers. The freshman baseball team of 1938 went undefeated and in April the “flashy Virginia catcher” homered and caught Harold Brosnan’s 14-strikeout performance of Washington and Lee.9 Harman, McCann, and Brosnan all played professional baseball.

With the two sophomores, the Cavalier basketball team went 15-5 in 1938-39, after going 6-10 the year before. They won the Big Six Virginia state championship amongst the other Virginia universities and went 10-2 against state opponents. They won their last five games of the season.

Harman, listed at 6-feet-6 (he was really a few inches shorter), began his varsity career with 13 points over the Young Italian American Progressive Club. The “big, rangy” center just missed all-state honors scoring 186 points, second to Armand Feldman.10

In his first varsity baseball game in 1939, Harman drove in four runs with a double and triple against Haverford.11 The team finished 14-6 with three of the six losses coming over the last four games. The year before, the Cavaliers were 8-8. The turnaround was in large part because of McCann and Harman.

In June 1939, coach Gus Tebell led 17 players to Cooperstown, New York, to take part in a college tournament at the new Hall of Fame’s Doubleday Field. They played two tune-up games against Rutgers and New Brunswick on the way up before taking on Ivy League champion Cornell and Illinois Wesleyan on June 15 and 17. The event ended in a three-way tie. Virginia defeated Cornell 8-1 on Thursday. Cornell won 3-2 in 10 innings over Illinois Wesleyan on Friday. Virginia lost to Illinois Wesleyan 10-9 in the Saturday finale. The Cavaliers lost in the bottom of the ninth after leading 7-2 early. With a chance to go ahead, Harman was walked to load the bases in the top of the ninth with the score tied, 9-9. Virginia did not score. Harman ended with one hit in each game.12

Back on the hardwood, the 1939-40 basketball team was even better, going 16-5. Harman was one of four starters returning and was the team’s sharpshooter. The January 13 Richmond Times-Dispatch called him “big, rangy, active and husky” as he scored half the points against Medical College (20 points), Hampden-Sydney (20), William and Mary (19), and Roanoke College (17).

After Harman scored 12 of the team’s 34 points in a win over Virginia Tech on January 29, the paper said he “rates with the State’s finest.” In early February, Harman’s 165 points and George Washington guard Red Auerbach’s 102 points were the tops in the state.13 George Washington, averaging more than 50 points a game, was slowed by a Cavalier defense in early February but still won 35-32 in overtime.

Harman bruised his leg soon after and entered the hospital, missing games to state champion Washington and Lee (loss), VMI (win), and Richmond (loss). With the state championship out of reach, the season ended with a win over Virginia and 12 points from Harman. The Associated Press named McCann and Harman all-state. Harman led the state with 217 points, just under 13 points a game.14

Back on the diamond a few weeks later, McCann and Harman were two of seven returning starters. Harman hit sixth as a junior in 1940. The team won the state title behind an 18-4 record.

Harman also began to pitch, striking out three in a perfect ninth against Pittsburgh and allowing one run on seven hits in seven relief innings in a 12-11 win over Michigan. He also had two doubles and three runs in that game. Tebell insisted that Harman only pitched “in case of need.” In mid-April he was hitting .360 with four doubles, a triple, and two homers.15 The “need” continued with five innings of two-hit ball against Virginia Tech and a tally of two runs on six hits given up over 13 relief innings.16

In the big game of the season, Virginia moved to 10-2 after Harman outpitched undefeated Richmond and top pitching prospect Porter Vaughan, 2-1. Harman allowed one run on two hits in the first and then no-hit the Spiders the rest of the way. He struck out 10 and retired the last 12 batters in a row.17

Early newspaper accounts had Harman facing off against Vaughan again before 4,000 fans in Charlottesville in the season finale. But instead, Harman caught reserve pitcher John Willey and he spotted Richmond three runs in the first. Virginia lost 5-4. Harman was 0-for-3. Porter Vaughan signed an $8,000 bonus contract with the Philadelphia Athletics after the season.18

Harman had one more year to go, a memorable 1941 that consisted of an NIT berth, his university degree, his debut with the Phillies, and his enlistment in the US Marine Corps.

For men coming of age in 1941, the time before Pearl Harbor was different. One wrote, “For me and my generation 1941 was not a year of Pearl Harbor and war, but of peace, the last year of peace, a shaky, fraying, disintegrating peace, but nonetheless peace.”19 By the end of World War II, more than 300 Virginia alumni had died in the war.20

Harman’s last year of basketball at Virginia ended at the National Invitational Tournament, then bigger than the NCCA Tournament, in March at Madison Square Garden with an 18-6 record. Harman and McCann combined for 42 points in the season opener and kept rolling. The pair and sophomore Dick Wiltshire finished in the top 10 in state scoring.21 Two years after graduation, in 1943, the Richmond Times-Dispatch conducted a fan poll of the top players in University of Virginia history, McCann was one of the top six players selected. Harman finished seventh with 59 votes.22

Harman also continued to be a school leader as team captain, a part of the Inter-Fraternal Council as a member of Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity, and as the 1940-41 student body president.

For the 1941 basketball season, the Cavaliers were known for their offense and defense, a rarity for the era. The team’s January victory over an undefeated Tennessee team, 41-30, when Harman had 18 points, propelled the Cavaliers to the NIT in mid-March.

Harman battled for the state scoring lead all season, as the Cavaliers brought in large crowds, as they cheered Harman’s 41-40 game-winner on what a newspaper described as the flight of a “snowbird” type pass from McCann at William and Mary in February.23

To finish the regular season he scored 15 points in his prep hometown of Alexandria in a win over George Washington and then before 3,000 home fans, in what was believed to be his last collegiate game, he had 27 points in a win over Washington and Lee. He finished with 351 points, a 16-point-a- game average, to win the state scoring championship.

Everyone believed the basketball season was over. Players took exams and McCann and Harman prepared for their final baseball season. Three weeks later, the NIT committee decided that the Cavaliers’ January win over Tennessee was worthy of an invite to the eight-team tournament. Virginia, without the benefit of playing for nearly a month, was invited to play CCNY in New York City.

Against 1940 NIT runner-up CCNY, the Cavaliers closed to within 23-19 at the half but soon were without their two stars. Harman fouled out five minutes into the start of the second half. McCann followed five minutes later. Virginia lost 64-35.

“There was no way we could beat a good New York team,” said McCann. “New York was so much better than we played down there. … (With the layoff) we were a long way from being organized for the NIT.”24

Virginia basketball did not make another postseason until 1972. That included six seasons under coach McCann, who went 40-106 (1957-63).25

Back on the diamond in spring 1941, Harman was listed at 205 pounds and hit cleanup behind second baseman McCann. His seven home runs remained a school single-season record until 1976.26 The team faltered, though, finishing 11-8, losing five of seven late in the season after a 5-0 start.

In late May both McCann and Harman signed professional deals. McCann to the Petersburg Rebels of the Virginia League and Harman to the last-place Philadelphia Phillies on May 28, after commencement.27

After signing, Harman remained a civilian, waiting for his draft number to be called. The Phillies, also seeing the writing on the wall, took just about anyone to get better and field a team. In a 1991 recollection, Sports Illustrated noted, “The inevitable dilution of talent eventually required team owners to make do with the oddest, and perhaps the most inept, contingent of players ever seen on major league playing fields.”28

Like a tall, rangy basketball player who could catch and pitch.

Harman was one of four catchers for the Phillies and was one of the tallest players in the majors. He also pitched. In the 1930s, 83 players pitched at least 50 innings and had at least 300 at-bats in the minors. None made the majors. A few Negro League players had done so, but again, it was rare.29

Harman made his major-league debut on June 17, 1941, making the last out as a pinch-hitter in an 11-3 loss to the Cardinals against Mort Cooper on an 84-degree day in St. Louis.30

On June 25, 1941, the day Joe DiMaggio hit in his 37th straight game, Harman was a two-way reserve. He pinch-hit in the eighth in game one of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field, fouling out, before catching the ninth. In game two, he pitched the ninth inning and gave up one run on a single, a sacrifice, and another single in a 5-1 loss.31

For the season Harman had a 4.85 ERA in five appearances and 13 innings. He did pitch a perfect eighth in a loss to the Pirates on July 23 that included retiring Vince DiMaggio. He pitched three innings on the mound against the Giants on September 23 in his last pitching appearance.

After going hitless the month of June (0-for-5) and July (without an at-bat) Harman ran for Phillies catcher Bennie Warren in the seventh inning on a 96-degree day in St. Louis on August 2. He caught the seventh and the eighth before coming to bat against Cardinals starter Howie Krist in the ninth. Harman singled to left field to lead off the ninth and scored on Jim Carlin’s home run, finishing off an 11-7 defeat. Harman played seven more games as a reserve going 1-for-14 (.071). On September 28 at Ebbets Field, he flied out to left against Bob Chipman in the ninth. It was the first of 51 career wins for Chipman over a 12-year major-league career and the last game for Harman.

Harman went to Marine boot camp in July 1941 in Parris Island, South Carolina.32 In anticipation of the United States entering the war, boot camp was reduced from eight weeks to four.33 It consisted of marching, parades, drilling, firing a rifle, and learning how to clean, disassemble and reassemble the rifle.34 The “lucky ones” lived in Quonset huts by the sandpits. Others lived in tents, in the “oppressive heat” of a South Carolina humid summer.35 After Parris Island, Harman was assigned to the officer training cadre training officer cadets in 1941-42.36 He was discharged after that but joined again prior to the 1945 Battle of Okinawa.

In late December 1941, Harman assisted McCann with the Virginia freshman basketball team while coach Tebell was away at the Rose Bowl as an official. The game had been moved from Pasadena, California, to Durham, North Carolina, because of fears of a Japanese attack on the West Coast following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.37

Harman and McCann both fought in the Pacific in 1945. McCann, a paratrooper, was hit in the neck by shrapnel at Iwo Jima and received two Purple Hearts.38 Harman was a part of the invasion of Okinawa in April 1945. In 1942 the Phillies had not heard from Harman. Reports had him enlisting in the Marines, but also undergoing treatment for an old ankle injury. He was released by the Phillies in May 1942.39

Harman was added to the faculty of the Augusta Military Academy in April 1942.40 He did, however, play at least one more pro season. As an outfielder and catcher, he played in 26 games for the Petersburg (Virginia) Rebels of the Class-C Virginia League in 1942. He hit .197 with four doubles and one home run. The Rebels were 74-52 and finished third in the Virginia League for manager Steve Mizerak.

In the fall of 1942, Harman began working as a teacher and coach in the Waynesboro (Virginia) public schools. He resigned in March 1943.41 Before resigning he married Janet Lorraine Cline in early 1943.42 In November 1943 he was a part of a group of former basketball players playing for the DuPont company. DuPont is where he spent his career after the war.43 He was listed on the roster of the Wellsville Yankees in 1944, but no statistics could be located and it is not known if he ever played.

In 1945 and 1946 he served as an assault amphibious vehicle crewman. In 1945 Harman took part in the invasion of Okinawa, serving with the 1833 3rd Amphibious Corps. “Crewmen likely rotated between ship to shore transporting casualties, casualty replacements, and supplies, working on tractors that needed repairs, and manning a machine gun in a nearby defensive position so all of the above and other things like getting sleep and eating could be accomplished,” a Marine Corps historian told the author.44 The 80-plus-day battle was the largest amphibious landing in the Pacific Theater.

The Allies faced 155,000 Japanese soldiers and another 500,000 civilians on the island of Okinawa, 350 miles from Japan. The enemy set up positions above the terrain and overlooked the terrain.45 The Allies not only had to advance over deserted terrain, of which Harman’s Amphibious Corps helped bring them forward, but also through knee need mud with little sleep, food or dry clothes.46

Some well-known fellow Marines on Okinawa who played in the majors were future Yankees All-Star outfielder Hank Bauer, Dodgers All-Star first baseman Gil Hodges, and longtime Braves announcer and pitcher Ernie Johnson Sr.47

Harman returned to the States and settled into a 41-year marketing career with DuPont’s textile fibers department, retiring in 1984 at the age of 65 but remaining as a consultant for the company. His marketing career took him to watching models strut down runways in Paris and New York as the company promoted its new Lycra product and had some of its best years.48 He died at the age of 88 on September 22, 2007, in Greenville, Delaware. He had two sons, William Bell Harman Jr. and Thomas Asher Harman. At the time of his death he had three grandsons and a great-granddaughter.49

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com. Point totals and other statistics from game reports at the University of Virginia are from the Richmond Times-Dispatch from 1938 to 1941.

Notes

1 Early family information via the 1920, 1930, and 1940 Censuses. According to the Census, in 1930 about 40 percent of the population owned a radio.

2 “Rural Life in Virginia,” Virginia Museum of History and Culture, viewed September 26, 2020. virginiahistory.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/rural-life-virginia.

3 “Large Student Enrollment in State Expected,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 22, 1933: 7.

4 “Scholarship, Books Given to Alexandria High School,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 11, 1938: 4.

5 Ron Heinemann, “The Great Depression in Virginia,” Encyclopedia Virginia, viewed September 26, 2020, encyclopediavirginia.org/great_depression_in_virginia#start_entry.

6 Heinemann.

7 Information about Episcopal High is from the 1935, 1936, and 1937 Whisper yearbooks and research done by school archivist Laura Vetter.

8 Whisper yearbooks.

9 “Brosnan Whiffs 14 as Va. Frosh Defeat W&I,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 13, 1938: 15.

10 “Four Maroons on All-State Cage Team,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 1, 1939: 15; “Virginia Star,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, December 27, 1939: 8.

11 “Haverford Nine Is Turned Back,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 31, 1939: 18.

12 “College Series Ends in Three-Way Tie,” Freeman’s Journal (Cooperstown, New York), June 21, 1939: 1-2.

13 “Virginia Risks Court Records Against G.W.,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 3, 1940: 13. Auerbach, the future Hall of Fame coach, finished with 162 points.

14 “3 Schools Contribute to All-State Quintet,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 24, 1940: 14.

15 “Spiders Risk Perfect Record Against Cavalier Nine Today,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 19, 1940: 20.

16 “Virginia Engages Tar Heel Nine This Afternoon,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 25, 1940: 17.

17 Tom Wiley, “Harman Hurls 2-Hit Game as Cavaliers Defeat Spiders,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 1, 1940: 10.

18 Tom Wiley, “Cavaliers Defeat Spiders 5-4,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 18, 1940: 12. Vaughan went 2-11 with a 5.83 ERA in 24 games in the majors (1940-41, ’46), and was also an Army captain.

19 Ron Briley, “Baseball and Other Matters in 1941,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, January 2002, abstract, researchgate.net/publication/236794782_Baseball_and_Other_Matters_in_1941_review.

20 Jennings L. Wagoner and Robert L. Baxter, Jr. “Higher Education Goes to War: The University of Virginia’s Response to World War II,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 100, no. 3 (1992): 399-428. Accessed September 6, 2020. jstor.org/stable/4249294.

21 “Cavalier Five to Meet Legion in Return Go,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 6, 1941: 14.

22 Dick Williamson, “Pinck, Knox, Spessard, McCann, Iler Make All-Time ‘Big Six,’” Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 17, 1943: 12.

23 Morris Siegel, “Cavaliers Nose Out William and Mary 41-40,” February 12, 1941: 16.

24 Chauncey Durden, “The Sportsview,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 23, 1980: 36.

25 In 1976, McCann and Wiltshire watched sixth-seeded Virginia upset North Carolina in the “Miracle in Landover” at the ACC Tournament. Virginia then lost to DePaul in their first-ever NCCA Tournament appearance and third-ever postseason.

26 In 1976 Tony Zentgraff broke the single-season record of seven homers that had been set by Harman and tied by Don Aichol (1951), Chuck Arnold (1956), and Pete Anderson (1974). “Cavalier Breaks HR Mark with 8,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 15, 1976: 58.

27 “Bill Harman Signs Contract with Phillies,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 30, 1941: 12.

28 Eventually 428 major leaguers served in the armed forces. William Jeanes, “Baseball in World War II,” Sports Illustrated, August 26, 1991, viewed September 22, 2020, vault.si.com/vault/1991/08/26/baseball-in-world-war-ii-fdr-let-baseball-continue-so-we-had-a-pastime-played-by-graybeards-no-beards-and-other-marvels.

29 Negro League and major-league Hall of Famers Martin Dihigo, Bullet Rogan, and Leon Day all were two-way stars in the 1920s and ’30s. After Ruth, another player didn’t have 50 innings and 300 at-bats until Shohei Ohtani did so in 2019.

30 “MLB Flashback: Bill Harman, Alan Knicely, Jon Rauch.” News Break. Accessed September 6, 2020. newsbreak.com/virginia/bridgewater/news/

1585330238033/mlb-flashback-bill-harman-alan-knicely-jon-rauch. The Retrosheet and Baseball-Reference play-by-plays of the game both describe the type of out as “unknown.”

31 Boxscore, June 26, 1941, National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives.

32 “William Bell Harman page,” Togetherweserved.com. Accessed September 6, 2020. marines.togetherweserved.com/usmc/servlet/

tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=ShadowBoxProfile&type=Person&ID=362425.

33 “Training for War,” US Marines website, mcrdpi.marines.mil/Portals/76/Docs/CentennialCelebrationBook/MCRDPI-history-book-4.pdf.

34 James Salerno, “Joining the Raiders,” interview by National World War II Museum, 2015, Digital Collections of the National WWII Museum, National WWII Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana. ww2online.org/view/james-salerno.

35 Don McLoud, “Parris Island in the ’40s: A Rude Awakening for One New Yorker,” Island Packet (Bluffton, South Carolina), October 15, 2015, Accessed September 20, 2020. islandpacket.com/latest-news/article39413739.html.

36 Edward Nevgloski (chief of Marine Corps History and director of Marine Corps History Division) in email with author, September 2020.

37 Bill Diehl, “Billy McCann Named Coach of Cavalier Frosh Cagers,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 31, 1941: 15.

38 Morris Siegel, “Fork Union Position Agrees with McCann,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 16, 1945: 31.

39 “Missing Phil Discovered,” April 30, 1942, National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives.

40 “Harman Joins Augusta Staff to Replace Craft,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 16, 1942: 14.

41 “Harman to Coach Waynesboro,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 27, 1942: 14.

42 Barton Pattie, “Virginia Sports Reel,” Free Lance Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), February 9, 1943: 9.

43 “Al Hawkins Coaches Du Pont Cage Team,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 12, 1943: 16.

44 Nevgloski.

45 “Battle of Okinawa: Operation Iceberg,” World War II magazine / Historynet.com, June 2005, accessed September 20, 2020. The Allies faced 155,000 Japanese soldiers and another 500,000 civilians on Okinawa, an island 350 miles from Japan. Marines sailed from the West Coast of America to Hawai’i to Guam before continuing to Okinawa. The Allies landed on the Western side of the island as the “Japanese chose to dig deep and fight on their terms,” away from the beach and overlooking terrain.

46 Seth Paridon, “The Invasion of Okinawa: One Damned Ridge After Another,” April 15, 2020, National World War II Museum, accessed September 20, 2020, nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/okinawa-invasion-1945. The Japanese were holed up in caves that dotted the Awacha Mountain range. The topography of ridge lines and lack of vegetation favored the enemy, making the caves difficult to reach. The amphibious tractors got stuck in the mud and tanks were “knee-deep in mud.” The Allies continued to advance while getting shot at by the Japanese from an elevated position. The rains allowed for no sleep, little food, or dry clothes. “Generally a Marine could take three or four steps before his boondockers, already caked in inches of mud, were literally sucked off his feet,” said Seth Paridon, who took part in the invasion. “(The Marines’) forte is amphibious landing and they took us under their wing,” said Len Lazarsrick, who was part of the invasion. The Japanese had embedded coconut logs on the beach, facing out to the sea at 45 degrees to deter amphibious vehicles from landing. Soldiers had to jump out and go on foot, he continued. In May, soldiers had to deal with monsoon season as well. “The foxholes would fill up with water and you had to bail them out when there was an air raid.” – air raids, sometimes a half dozen times a night, left little time for sleep. … If you got four hours of good sleep, you did good,” said Melvin Munch. “Your view of the warfare is not the big picture, it’s your narrow view. And part of that view is trying to stay alive,” continued Lasarick, whose 96th Division was trained by the Marines. As the battled continued the “smell of war stayed with you constantly. You hated to breathe the odor of death,” said Munch. In the end the Allies suffered 50,000 casualties and the Japanese suffered 100,000. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki essentially ended the war in the Pacific in August and avoided a much larger invasion of Japan. Len Lazasrick, “Segment 3,” interview by National World War II Museum, 2015, Digital Collections of the National WWII Museum, National WWII Museum, ww2online.org/view/len-lazarick#segment-3 and Melvin Munch, “Battle of Okinawa,” interview by National World War II Museum, 2015, Digital Collections of the National WWII Museum, National WWII Museum, ww2online.org/view/melvin-munch#boot-camp-to-okinawa.

47 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime,” accessed September 20, 2020, baseballinwartime.com/marine_corps.htm.

48 “Opening New Doors, Retiree Locks into Construction Firm,” Wilmington (Delaware) News Journal, February 4, 1995: 29.

49 Obituary, Charlottesville (Virginia) Daily Progress, September 25-27, 2007, viewed September 20, 2020 legacy.com/us/obituaries/dailyprogress/name/william-bell-harman-obituary?n=william-bell-harman&pid=95048587.

Full Name

William Bell Harman

Born

January 2, 1919 at Bridgewater, VA (USA)

Died

September 22, 2007 at Greenville, DE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.