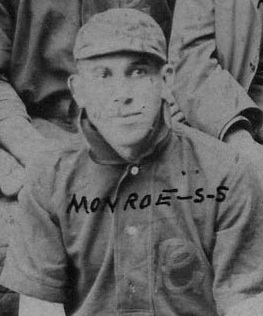

Bill Monroe

One of the most charismatic players of his era, Bill Monroe starred for several leading African-American professional teams from 1899 until his untimely death in 1915. In the field, he excelled at third, short, and second. At the plate, his speed and power enabled him to shine either as a lead-off man or in the middle of the order. From the coach’s box, his showmanship endeared him to a generation of fans. “He courted attention from the moment he entered the ground until the close of the game,” Sol White recalled of Monroe.1 Teammates Andrew “Rube” Foster and Dan McClellan considered him the greatest ballplayer they ever saw.2

One of the most charismatic players of his era, Bill Monroe starred for several leading African-American professional teams from 1899 until his untimely death in 1915. In the field, he excelled at third, short, and second. At the plate, his speed and power enabled him to shine either as a lead-off man or in the middle of the order. From the coach’s box, his showmanship endeared him to a generation of fans. “He courted attention from the moment he entered the ground until the close of the game,” Sol White recalled of Monroe.1 Teammates Andrew “Rube” Foster and Dan McClellan considered him the greatest ballplayer they ever saw.2

William S. Monroe was born on March 16, 1878, in Knoxville, Tennessee.3 He was the youngest of Archie and Rosa (née Lattimore) Monroe’s five children. His father was a Tennessee native; his mother was born in Mississippi. Archie served in the U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery during the Civil War. After the conflict, he served as a minister in the AME Zion Church. The family relocated to Chattanooga during William’s teenage years.4 In his father’s church choir, he developed a notable bass voice.5

While his earliest baseball days are seemingly lost to time, a Monroe played third and led off for Nashville’s Rock City Unions as they journeyed north to battle the Chicago Unions for a “colored championship” on June 26, 1898.6 That offseason, Chicago Unions manager William Peters signed “Monroe of Nashville, Tenn.”7

He immediately made a “great hit” with the Unions.8 On June 11, as Chicago hammered the visiting Cuban X-Giants, 16-6, Monroe homered and singled, and scored three runs. Two weeks later, the teams met again. Although the Unions lost, 7-5, he again homered and singled, scored two runs, and earned praise for “his magnificent fielding.” 9

“Short, chunky, and plucky looking,” the righthanded Monroe stood 5-foot-7 and weighed 151 pounds.10 He moved to second for the 1900 season and batted cleanup. Beginning in late June, the Unions and X-Giants barnstormed together for a week through Illinois and Indiana.11 When the series concluded, Monroe left with the X-Giants. On July 2 he debuted with his new team in Greenville, Pennsylvania, playing second and producing two hits from the cleanup spot.12 He soon took over shortstop and the leadoff role.

Monroe began the 1901 campaign at the hot corner, with a New Haven correspondent calling him “one of the best third basemen seen here in years.”13 Soon he was back at short, and a Philadelphia sportswriter reviewing the region’s thriving amateur scene proclaimed, “There is not a short stop around this vicinity who has anything on Monroe, the Cuban X-Giants’ husky player.”14 He battled injuries but otherwise effectively alternated between leadoff and cleanup slots in the batting order.

In 1902, Monroe again started at third before moving to short. He fell in the batting order, often hitting sixth, seventh, or eighth. On July 20 he broke his left ankle making a play in the field.15 Less than three weeks later, he was back, before again drifting out the lineup that September.

Perhaps seeking a fresh start, Monroe signed with the Philadelphia Giants before the 1903 season. He joined many former “Cubes” already with the “Phillies,” including pitcher-outfielder Kid Carter and infielder-manager Sol White. Playing short and batting leadoff, he impressed onlookers as “one of the slickest fielders in the business” and “the best player on the Philadelphia Giants’ team.”16 Yet a healthy season again eluded him. On August 7, playing in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, he broke one rib and tore muscles from another colliding with a baserunner while covering second base.17 Monroe returned on September 12 as the Phillies opened a seven-game “colored baseball championship of the world” with the Cubes.18 He banged out two hits against Rube Foster but, playing first, “made no effort to reach” for a throw, enabling a key run to score.19 The Phillies lost the game, 4-2. Monroe was shelved for the rest of the series, eventually won by the Cubes.

Finally, in 1904 he enjoyed a healthy campaign. With Johnny Hill at third, Monroe at short, Charlie Grant at second, and White at first, the Phillies possessed “the fastest infield of any club that comes here,” a Wilmington sportswriter opined.20 On June 6, Monroe hit for the cycle off Ralph Caldwell as the Giants shut out Trenton’s Roebling team, 9-0.21 That September, the Phillies again squared off against the Cubes. Monroe went hitless in the three-game series.22 But behind Foster, who had jumped teams after the 1903 campaign, the Phillies triumphed.

Although the always-versatile Monroe caught one game with Philadelphia and pitched another, he mostly manned the hot corner in 1905.23 He usually batted third or fourth in the order. Per baseball historian Phil S. Dixon’s research, he stole 37 bases while accumulating 49 extra-base hits (26 doubles, a team-leading 15 triples, and eight home runs).24 Among the Phillies, only outfielder Pete Hill likely also reached this statistical plateau. Among major leaguers, only Honus Wagner and Sam Mertes did so in 1905.25 Monroe accomplished these feats despite missing several weeks after being hit by a pitch in early July.26

The Phillies stayed in continuous motion as they barnstormed. Showdowns against other black professional teams, although memorable, were limited. In 1905 the Phillies played 23 such games. The remainder of their schedule was against white squads: 19 against minor-league teams, the rest against semi-pros. In either case, these opponents often featured past or future major leaguers. The Phillies made several sweeps through New England and into the hinterlands of New York and Pennsylvania. But mostly they hugged the Mid-Atlantic Seaboard; Atlantic City, Wilmington, Chester, Philadelphia, and New York were common stops. Per Dixon’s research, the squad amassed a 128-23-3 record.27

By 1905, Monroe’s showmanship was already renowned. In the late 19th century, “coachers” of both races, especially Arlie Latham and Clarence Williams (later one of Monroe’s X-Giants teammates), refined trash-talking the opposition and clever sparring with the fans. Monroe may have been its greatest practitioner, although his running in-game chatter was hardly confined to the coaching lines.

He was at once droll and vivacious, with a “foghorn voice” broadcasting his commentary throughout the cozy parks.28 Before a rally: “Oh! Lord, have mercy on us for what we are about to do. Farewell! Goodbye.”29 As he snapped up grounders: “You’re out, chile.”30 Singing as he approached the plate: “The ball is going out and a run is coming in.”31 Towards the grandstand, after defeating their local nine: “This picnic will be repeated on Wednesday and Thursday of this week.”32

On occasion, Monroe echoed what baseball historian Lawrence D. Hogan terms the “racist societal influence on entertainment” still common in America in this era and reflected in its minstrel shows and coon songs.33 In 1908, for example, a teammate playing left field survived a tumble chasing a foul fly. “If dat coon in de left pasture got hurt we puts anoder man in his place,” Monroe told the grandstand, “If I gets hurt, de game stops.”34 Hogan notes of such clowning: “Making a fool of oneself on the diamond was part and parcel of taking admission money from as many white folks as possible. While doing so, the ‘fool’ as artist might of course transcend the clown role in the enthusiasm, fun, and creative expressiveness of what came to be viewed as baseball art.”35

Contemporary accounts often acknowledged Monroe’s artistry. “Thursday’s game was really an entertainment,” a Pottsville, Pennsylvania, scribe reported in 1900, “the bitterness of defeat having been softened by Cuban X-Giant wit, so much so that the audience gave its applause equally to visitors and home club.”36 Five years later: “[Monroe] kept the grandstand in a continual roar with his funny sayings, and although Allentown lost he kept the local fans in good humor throughout the entire game.”37 From Buffalo in 1908: “Third Baseman Monroe was a big part of the show. Where he found so many things to talk about no one knows, but he was just bubbling over all the time, and livened the game with his innocent fun.”38

Monroe’s wit helped to sooth the pain his teams commonly administered to their opponents. Yet it did not always obscure his competitiveness — nor that of his teammates — that occasionally exposed underlying racial tensions. At the plate against a Wilmington team on May 15, 1903, he was ruled out for interfering with catcher Harry Barton. Monroe “became very angry and used some bad language” beefing with the umpire before Barton called two policemen to quell the controversy.39 A Wilmington sportswriter editorialized after the incident, “There are plenty of white teams that play ball and the better class of baseball followers would rather see them.”40 A year later, in Camden, a dispute between Grant and an umpire led to black and white fans confronting each other on the field with “every indication of a bloody battle, when the police, with drawn clubs, charged the crowd and prevented any further clash.”41 In 1905, again in Wilmington, Monroe claimed baserunner Red Hinton struck him. “The players crowded on the field and the argument became warm, but luckily no blows were struck.”42 Local newspapers again argued for a color line to be drawn.

Negotiating a segregated time as the primary public face of a dominant African-American team, all the while starring in the field, was no mean feat. Yet the team’s management was stingy. Foster later stated, “The whole team was making only $100 out of Sunday games and a proportionate amount for other games. In spite of the fact that we were the best colored team in baseball, that was all Walter Schlichter, the owner, could or would do for us.”43 Monroe began the 1906 season with the Phillies but soon joined Foster in signing with the upstart Philadelphia Quaker Giants.44 Schlichter and powerful New York booking agent Nat Strong leaned on Foster and he returned to the Phillies’ fold.45 Monroe stayed with the Quakers, leading off, and playing either third or short.

By August, the Quakers’ financial backing evaporated.46 Monroe and several teammates joined the Brooklyn Royal Giants, founded two years earlier by African-American restaurateur John Connor. That September, the Royals fought the Phillies to a draw in a four-game series, with Monroe contributing five hits, five runs, and four stolen bases from the leadoff spot.47

In 1907 newspapers prominently featured Monroe as Royals visits neared, and sometimes labeled him the team captain.48 He manned third base and batted first or third in the order. The Royals fell short of the Phillies in the National Association of Colored Baseball Clubs’ inaugural season, but a three-cornered doubleheader on Sunday, August 25, suggested the team’s growing appeal. “More than 8,000 people crowded the stands and surrounded the field” including some “1,500 ladies, their pretty attire and vari-colored parasols adding color to the background.” Those in attendance included “President Harry Pulliam of the National League, Manager Billy Murray of the Phillies, Barney Dreyfuss of the Pittsburg Club, Ned Hanlon of the Cincinnati Reds, [Orval] Overall of the Chicagos … and others famous in baseball and politics.”49 The Royals lost the first game to the Phillies, who then edged the Hoboken team, 6-5.

“There is no mistaking it, Monroe is a ball player from head to heels,” wrote a correspondent as the 1908 campaign opened.50 Seamheads’ Negro League database documents a BA/OBP/SLG line of .337/.388/.505, 26 runs, 13 RBIs, and 10 extra-base hits over 24 games. From present-day newspaper databases, box scores with fielding statistics (outs, assists, and errors) are readily available for 52 of the Royals’ 1908 games.51 Of this sample, Monroe started 35 games at third, 14 at short, and one each at first, second, and in left field. Across all positions, he amassed 95 putouts, 139 assists, and nine errors — for a fielding percentage of .963. For his 35 games at third: 51 putouts, 87 assists, and four errors — a fielding percentage of .972 and a range factor per game of 3.94. For the second season in a row, Monroe then participated in the Cuban Winter League, playing 15 games at third. Baseball historian Gary Ashwill, in his analysis of these games, assigns him a fielding percentage of .973 and a range factor per game of 4.87.52 In 1908 major-league leaders among third basemen were Hobe Ferris with a fielding percentage of .952 and Bill Sweeney with a range factor per game of 3.67.

“There is no mistaking it, Monroe is a ball player from head to heels,” wrote a correspondent as the 1908 campaign opened.50 Seamheads’ Negro League database documents a BA/OBP/SLG line of .337/.388/.505, 26 runs, 13 RBIs, and 10 extra-base hits over 24 games. From present-day newspaper databases, box scores with fielding statistics (outs, assists, and errors) are readily available for 52 of the Royals’ 1908 games.51 Of this sample, Monroe started 35 games at third, 14 at short, and one each at first, second, and in left field. Across all positions, he amassed 95 putouts, 139 assists, and nine errors — for a fielding percentage of .963. For his 35 games at third: 51 putouts, 87 assists, and four errors — a fielding percentage of .972 and a range factor per game of 3.94. For the second season in a row, Monroe then participated in the Cuban Winter League, playing 15 games at third. Baseball historian Gary Ashwill, in his analysis of these games, assigns him a fielding percentage of .973 and a range factor per game of 4.87.52 In 1908 major-league leaders among third basemen were Hobe Ferris with a fielding percentage of .952 and Bill Sweeney with a range factor per game of 3.67.

The Royals posted the National Association’s best record in both 1908 and 1909 then, after the Association’s demise, the best winning percentage among eastern independent black teams in 1910. One game not in these ledgers: an October 8, 1909, match with the New York Highlanders. It seems to have been Monroe’s only appearance against a major-league team. While a box score is elusive, an onlooker reported that “the heavy hitting of [Harry] Buckner and Monroe were the features of the game.” The Royals played errorless ball, and triumphed, 9-6.53

Prior to the 1910 season, veteran infielder Grant “Home Run” Johnson left Brooklyn for Chicago, to join the powerful Leland Giants squad that Rube Foster managed and starred for. Royals owner Connor promptly accused Johnson of inducing his ex-teammates to break their contracts and follow him.54 Johnson was unsuccessful in these endeavors but, by mid-season, the Royals held a secret meeting over whether to “jump the team and form a club to be backed by a certain New York baseball fan, who is also interested in theatricals.”55 Connor was soon “informed of the meeting and gave notice that all the dissatisfied ones could go and that he would get new players.”56 The mutiny ended.

Foster, partnering with John C. Schorling, took the core of the Leland Giants into his next team, the Chicago American Giants. Catcher Bruce Petway handled a rotation of Charles Dougherty, Frank Wickware, Bill Lindsay, and Foster. Leroy Grant and Fred Hutchinson starred in the infield, while Frank Duncan, Pete Hill, and Andrew Payne manned the outfield. Monroe witnessed this lineup in March 1911, when the Royals battled the American Giants in a three-game series in Jacksonville.57 Two months later, he joined Foster’s squad, replacing Fred Goliah at second base and batting cleanup.58

The American Giants were likely the country’s finest black baseball team in this era. They regularly claimed the best record of the competitive Chicago semipro circuit and outpaced other regional black teams. By 1913, thanks to lengthy wintertime swings along the West Coast, they played over 200 games a season. Complimenting their teamwork, a Portland sports editor stated, “Those fellows are the greatest baseball machine I ever saw. They work together automatically.”59 Weeks later, a Seattle scribe noted the team was “so fast on the bases that they hit and run most of the time, for it is practically impossible to double them.”60

Seamheads identifies Monroe’s 1911 BA/OBP/SLG line with the American Giants as .322/.358/.411 and assigns him an OPS+ of 124. Yet in 1912, Monroe produced only one documented extra-base hit and an OPS+ of 51. He rebounded slightly in 1913 and 1914 but remained a below-average offensive player. After 1911, he moved down in the order, batting fifth, sixth, or seventh. Conjecture suggests he effectively executed the American Giants’ brand of “inside baseball” as he aged. Certainly, he remained a heady, aggressive baserunner. In a May 15, 1913, match versus the Nebraska Indians, “Black Bear, the Indian catcher, allowed a ball to get through him in the sixth inning, and Monroe went home from second base with the winning run.”61 Defensively, per Seamheads, his range factor slid over his four years with the American Giants, although his fielding percentage remained well above average. Among other black second basemen in this span, likely only Bingo DeMoss and Dick Wallace rivaled Monroe’s play at the position.

Monroe remained “a scream when he gets to cutting up” with his in-game commentary, and “one of Chicago’s most popular players” for his fieldwork.62 A decade earlier, either as a take on his name or as an appreciation for his clutch play, he was nicknamed “Money.”63 With the American Giants, possibly as he “has some nice stones on and some put away,” fans called him “Diamond.”64 An “idol with all the ladies,” Monroe never married, although he confessed to curbing the “late hours” of his youth.65

On March 16, 1915, at his parents’ home in Chattanooga, Bill Monroe died of tuberculosis. An Oregon newspaper reported that he “contracted the cold that later caused his death while touring the Pacific Northwest last spring” but still held down second base during the 1914 season.66 Monroe was buried in Chattanooga’s Forest Hills Cemetery. Soon after his death, playing on the West Coast, the Chicago American Giants honored him by wearing black crepe on their arms.67 The Sporting News, generally unconcerned with black baseball during this era, nonetheless relayed “the death of one of the greatest ball players the game has known. His skin happened to be black and he never shone in the majors, however. He was Monroe … those who have seen him play say he was a Lajoie and a Wagner, combined.”68

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Monroe’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, and the following sites:

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/

Notes

1 Sol White, “Sol White’s Column of Baseball Dope,” Cleveland Advocate, March 22, 1919. (Clipping within Monroe’s Hall of Fame file.)

2 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 16, 1926; W. Rollo Wilson, “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 3, 1931; W. Rollo Wilson, “Sports Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 11, 1931.

3 The only apparent source for his birth date is from his 1915 Tennessee Death Certificate. There his date of birth is typed as March 16, along with his age (at death) as 37, with his year of birth not completed. One could then derive his year of birth as 1878. Yet March 16 was also his date of death, as handwritten on the form. It is possible that whoever filled out the form mistakenly entered the same death date—once typed, once written—in two different locations. However, the 1880 census shows “Willie” as being two years old. March 16, 1878, therefore seems as reasonable a date as any.

4 For Archie Monroe’s background, see U.S. Colored Troops Military Service Records and City Directories available via Ancestry.com.

5 “Lloyd Was Greatest Infielder — Dismukes,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 15, 1930.

6 “Chicago Unions, 13; Rock City, 5,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1898.

7 “Chicago Unions Sign Contracts,” Chicago Tribune, January 1, 1899.

8 “Unions Play Mandel Bros. Sunday,” Chicago Inter Ocean, April 25, 1899.

9 “Unions Defeat Cuban Giants,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1899; “Unions Are Defeated Again,” Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1899.

10 “Colored Team Beat Allentown,” Allentown Morning Call, September 13, 1905; Billy Lewis, “Put A Crimp in the Tail,” Indianapolis Freeman, May 31, 1913.

11 “Chicago Unions, 10; Cuban X Giants, 5,” Chicago Inter Ocean, June 25, 1900; “Unions, 6; Cuban Giants, 3,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1900.

12 “Done Up by the Giants,” Greenville (Pennsylvania) Record-Argus, July 3, 1900.

13 “A Fourteen Inning Draw,” New Haven Morning Journal and Courier, April 30, 1901.

14 “Here’s the Gossip of all the Crack Amateurs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 28, 1901. As neither the Athletics’ shortstop tandem of Joe Dolan and Bones Ely nor the Phillies’ Monte Cross produced impressive campaigns in 1901, the correspondent may well have included the major leagues in his assessment.

15 “Hot Game with the Giants is Played,” Delaware County (Pennsylvania) Daily Times, July 21, 1902.

16 “Henry’s Fumble Lost the Game,” Camden Courier-Post, August 3, 1903; “General Sporting Notes,” Harrisburg Telegraph, August 20, 1903.

17 “Monroe Knocked Senseless,” Harrisburg Daily Independent, August 8, 1903; “Some Live Gossip About Future Stars on the Ball Field,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 16, 1903.

18 “Cuban X-Giants Win First Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 13, 1903.

19 Philadelphia Item, September 13, 1903.

20 “Hard Schedule for This Week,” Wilmington Evening Journal, May 23, 1904.

21 “Whitewash Brush for the Roeblings,” Trenton Evening Times, June 7, 1904.

22 “Phila. Giants Trim Cuban X-Giants, Foster Fanning 18 Men at Plate,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1904; “Cuban X Giants Land 2D Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 3, 1904; “Phila. Giants Win Championship,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1904.

23 Monroe caught Foster in a 4-3 victory over Haddington on May 13: see “Lost in Eleventh Inning, Philadelphia Inquirer, May 14, 1905. On September 1, allowing one earned run, he pitched the Giants to a 7-3 win over Atlantic City. See “Poor Fielding Lost Game, Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1905.

24 Phil S. Dixon, Phil Dixon’s American Baseball Chronicles – Great Teams: The 1905 Philadelphia Giants Volume III (Xlibris, 2010): 21, 34, 190-191, 241-242. Note Dixon could not unearth box scores for “nearly twenty games” while finding “a half-dozen additional games that have incomplete box score summaries.” Very reasonably, then, one might assume Monroe’s 37 SB, 49 XBH counts were considerably higher.

25 Per Baseball-Reference’s play index.

26 Dixon, The 1905 Philadelphia Giants, 147.

27 Ibid., 21-26.

28 “Giants Take First 3 to 0 and Now Lead League,” San Diego Union, December 7, 1912.

29 “Fast Colored Team Wins in Easy Style,” Anaconda (Montana) Standard, April 23, 1914.

30 “Quaker Giants Will Be Here Saturday,” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier-News, July 17, 1906.

31 “Altoona Won the Game,” Altoona Tribune, September 10, 1903.

32 “A Picnic, Eh,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Daily News, July 6, 1904.

33 Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2006): 35.

34 “Blacks Beat Stars,” Syracuse Herald, April 27, 1908.

35 Hogan, Shades of Glory Hogan, Shades of Glory, 35.

36 “Defeated by the Darkies,” Pottsville Miners’ Journal, September 14, 1900.

37 “Base Ball,” Allentown Leader, September 13, 1905.

38 “Dry Docks Down Mencos; Giants Defeat Pine Ridge,” Buffalo Courier, May 18, 1908.

39 “Victory for the Athletics,” Wilmington News Journal, May 15, 1903; “Defeated the Giants,” Wilmington Evening Journal, May 15, 1903.

40 “Defeated the Giants.”

41 “Row Kicked Up Over in Camden,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 1904; “Scenes of Rowdyism at Saturday’s Game,” Camden Courier-Post, May 16, 1904.

42 “Fight at Ball Game Was Narrowly Averted,” Wilmington Evening Journal, May 17, 1905.

43 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 16, 1926.

44 “Philadelphia Giants Win,” New York Press, April 2, 1906; “Monroe Played with Phila. Quaker Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, April 11, 1906.

45 “Rube Foster Jumps to the Philadelphia Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, April 18, 1906.

46 “Wanted Money Badly,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 10, 1906; “Baseball Is Ended for Keeps,” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier News, August 20, 1906.

47 “Philly Giants Win in First,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 11, 1906; “Royals Smother Philly Giants,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 12, 1906; “Philly Giants Give Royals a Trimming,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 14, 1906; “Royal Giants Have Fun with the Phila. Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, September 16, 1906.

48 For mentions of Monroe as captain, see “Royal Giants Attraction in Hoboken,” Jersey Journal, May 11, 1907; “Owego’s Game,” Waverly (New York) Free Press and Tioga County Record, July 26, 1907. Note the latter source identifies Monroe as the team’s manager too.

49 “Hoboken Loses Its First Game,” Jersey Journal, August 26, 1907.

50 “Tri-Staters Outbat and Outplay Giants,” Reading Times, April 21, 1908.

51 The 52 games: 4/20 vs Reading; 4/21 vs Reading; 4/26 vs Syracuse; 4/28 vs Scranton; 4/29 vs Scranton; 5/17 vs Pine Ridge; 5/30 vs Hoboken; 6/6 vs Howards; 6/7 vs Ridgewoods; 6/19 vs Benton; 6/20 vs Lansford; 6/25 vs Phila Giants; 6/26 vs Millville; 6/28 vs Loughlin Lycceum; 7/1 vs Naugatuck FD; 7/4 vs Howards; 7/4 vs Howards; 7/7 vs Pittsfield; 7/9 vs Pittsfield; 7/10 vs Stockbridge; 7/13 vs Phila Giants; 7/15 vs Millville; 7/16 vs Atlantic City; 7/17 vs Atlantic City; 7/18 vs Atlantic City; 7/19 vs Cuban Stars; 7/22 vs Pittsfield; 7/30 vs Hagerstown; 8/2 vs Cuban Stars; 8/2 vs Ridgewoods; 8/5 vs Bridgeton; 8/7 vs Atlantic City; 8/8 vs Atlantic City; 8/15 vs Howards; 8/20 vs Cuban Giants; 8/23 vs Phila Giants; 8/23 vs Ridgewoods; 9/2 vs Phila Giants; 9/3 vs Phila Giants; 9/4 vs Phila Giants; 9/5 vs Phila Giants; 9/8 vs Phila Giants; 9/9 vs Phila Giants; 9/10 vs Cuban Giants; 9/12 vs Cuban Giants; 9/14 vs Cuban Stars; 9/14 vs Newport; 9/20 vs Cuban Stars; 9/20 vs Ridgewoods; 9/27 vs Cuban Giants; 9/27 vs Ridgewoods; 9/29 vs Phila Giants.

52 Gary Ashwill, “Brooklyn Royal Giants in Cuba, 1908,” Agate Type, https://tinyurl.com/yaj893zu, accessed December 20, 2018.

53 Lester A. Walton, “In the Sporting World,” New York Age, October 14, 1909.

54 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, April 14, 1910.

55 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, August 18, 1910.

56 Ibid.

57 Lester A. Walton, “In the World of Sport,” New York Age, March 30, 1911.

58 For his debut, see “Giants Trounce Cuban Stars,” Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1911.

59 “Here’s a Hot One from the Southern Wilds,” San Francisco Call, March 20, 1913.

60 “Negroes Beat Seattle in First Game by Playing Big League Ball,” Seattle Daily Times, April 5, 1913.

61 “Giants Trounce Indians, 2-1,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1913.

62 “The American Giants,” Indianapolis Freeman, April 19, 1913; Cary B. Lewis, “Lewisisms,” Indianapolis Freeman, May 10, 1913.

63 The earliest reference to “Monny” noted by the author: “Won from Giants by Close Margin,” Camden Post-Telegram, April 24, 1904.

64 Cary B. Lewis, “Lewisisms,” Indianapolis Freeman, May 16, 1914; Cary B. Lewis, “American Giants Win with Ease,” Indianapolis Freeman, June 20, 1914.

65 Cary B. Lewis, “Americans Lose First Game,” Indianapolis Freeman, August 22, 1914; “Lewisisms,” May 16, 1914.

66 Roscoe Fawcett, “Evans’ Kick Costs Trip to Federals,” Portland Oregonian, March 24, 1915.

67 “Recruit Pitchers Beat Black Team,” Portland Oregonian, March 22, 1915.

68 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1915: 4.

Full Name

William S. Monroe

Born

March 16, 1878 at Knoxville, TN (US)

Died

March 16, 1915 at Chattanooga, TN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.