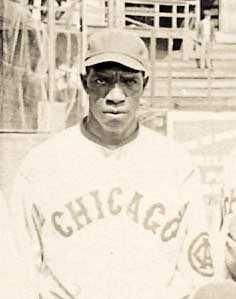

Bingo DeMoss

He was, by wide acclaim, one of the finest second basemen to play in the segregated era, as well as before the formal creation of a Negro League. Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss played alongside not only John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, but on various teams whose rosters included a figurative “Who’s-Who” of Black baseball in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

He went on to manage in the cities of Detroit, Akron, Cleveland, and Chicago, and even managed the West All-Stars in the 1936 East-West game. Historian James Riley called DeMoss “…the greatest second baseman in black baseball in the first quarter (of the twentieth) century . . . the consummate ballplayer, excelling at all phases of the game.”1

There are few known, verifiable details about DeMoss’ early life. Based on review of various official United States census documents,2 along with digitized marriage records3 and DeMoss’ draft registration for World War I, Elwood was born on September 5, 1889, in Topeka, Kansas, as the youngest of five children of Mansfield and Alie (Perkins) DeMoss. Mansfield was born in Tennessee in either 1844 or 1845. It is therefore likely that he was born a slave, and liberated by the end of the United States Civil War.

By 1910, Alie (alternatively spelled Eley in some official documents) was a widow, Mansfield having been 15 years her senior.4 She supported her family by working as a housekeeper in the Topeka area. Of note, that 1910 census lists Alie, 20-year-old Elwood, and the other children as able to read and write. Elwood achieved a seventh-grade education,5 which was a particularly impressive achievement, given the humble beginnings of the family and the challenges faced by the newly-liberated, non-White families throughout the nation.

Regardless, Elwood DeMoss was also a talented athlete, and while some accounts state that he began his baseball career in 1905 with the Topeka Giants6, it was more likely 1906.7 His first documented games as a professional came in 1910, for the Oklahoma Monarchs and the Kansas City Giants. The 20-year-old played second base for those teams that season, and displayed such prowess at bunting and defense that he returned to the Giants for the 1911 season, playing for manager “Topeka” Jack Johnson,8 who was also at the helm of the 1906 Topeka Giants. Of note, during his brief time with Oklahoma, DeMoss played alongside a young slugger, Louis Santop, the first of many future Hall-of-Famers with whom he would team.

James Riley, in his encyclopedia, summarized DeMoss’ skill set as follows: “A scientific clutch hitter with superior bat control and exceptional eye-hand coordination, he was a good contact hitter and could place the ball where he wanted. A natural right-field hitter, he was a skilled hit-and-run artist and a superb bunter . . . Jocko Conlon, who before becoming an umpire played exhibitions against the Chicago American Giants, said that DeMoss could drop a bunt on a dime.”9

While there is no definitive account of how DeMoss was anointed “Bingo,” the existing narrative is that it derived from his ability to “place a bunt anywhere he wanted on the field.”10 Kansas City Monarchs catcher Frank Duncan once observed that, “I’ve never seen a man bunt a ball like DeMoss. Looked like when you play pool and draw a ball back. How he did it, I don’t know, but he sure did it.”11

From Kansas, DeMoss joined the French Lick Plutos and then C.I. Taylor’s West Baden Sprudels in 1912. In 1913, 24-year-old DeMoss married Virgil Williams, a woman a year younger than himself. They would have no children, and she passed away in 1935 at the age of 45.

In May of 1915, DeMoss followed manager Taylor to Indianapolis, where he joined C.I.’s brother Ben Taylor, as well as Oscar Charleston and Dizzy Dismukes, in pacing the ABCs to a 37-25 record12 and a first place finish among the Western Independent Clubs. In two particular games against Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants, on June 21 and July 18, DeMoss scored three runs in eight at-bats, despite producing only one hit.13 Foster was later quoted as saying “’Bingo’ is a ballplayer at all times, and from head to foot. However, his big assets are from the shoulders up.”14

In Indianapolis, though, DeMoss ran into a bit of trouble. In one now-notorious incident during the fifth inning of a game between a White All-Star team captained by Donie Bush and Foster’s ABCs, umpire Jimmy Scanlon made a bang-bang call at second base that favored the White base runner. DeMoss, who had made the tag at second base and knew the runner should have been called out, charged the arbiter and punched him in the face.

Before the fight could really get going, right fielder Oscar Charleston raced in and hit Scanlon in the face as well, this time opening a wound and knocking the umpire to the ground. Players from both sides rushed the field, and only immediate police action prevented the potential riot. Charleston and DeMoss were both shuttled off to jail15 so the game could finish, and the maelstrom dissolved. Both players were later released on bail, and DeMoss was eventually fined five dollars after the case was tried the following December.16

Manager C.I. Taylor later said, “I am very grieved over the most unfortunate and degrading affair pulled off by DeMoss and Charleston. Umpire Scanlon was wholly blameless. His decision might have been questionable, but there is not one word that can be said justifying the perpetrators of that unfortunate and untimely happening . . . I believe that if DeMoss had any idea that things would have turned out as they did he would not have raised a hand to push the umpire. Remember we are not trying to shadow him for his actions. He needs no defense—he was wrong. But knowing him as I do, I am fully convinced that his conduct was worse than his heart.”17

Another incident occurred the following spring, in a pool hall owned and operated by DeMoss. In 1916, Judge James Collins, “ . . . of the criminal court, ordered Elwood DeMoss, colored, poolroom keeper and ball player, to the county jail because DeMoss had failed to pay a fine of twenty-five dollars and costs imposed by the court April 7 . . . members of the A.B.C baseball team began wondering where they would get a second-baseman to take DeMoss’ place . . .”. The court refused to release DeMoss early, after his conviction for allowing minors in his establishment, because the player had had the chance to pay his fine but “never set foot in the courtroom.”18

In 1917, DeMoss found himself playing for Foster’s American Giants, the team with which he would serve until 1925.During the offseasons before 1916 and 1917, “Bingo” traveled to Palm Beach, Florida, to play for Foster’s other squad, the Royal Poinciana Hotel team, one of the greatest squads ever cobbled together before the 1920 creation of the Negro National League. In addition to DeMoss at second base, the shortstop was John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, a man whom Babe Ruth called the finest player ever.19 Bruce Petway, possibly a better catcher than even Josh Gibson, was behind the plate, while Oscar Charleston and Pete Hill patrolled the outfield. It was an exhibition team that carried four future Hall of Famers on the roster, and they dominated the rival Breakers Hotel for two seasons. The latter team was no slouch-laden squad, featuring the aforementioned Louis Santop, along with Spottswood Poles, and Cyclone Joe Williams.

DeMoss had registered for the draft, but the Great War (World War I) ended before he was summoned to active duty. He replaced 35-year-old Pete Hill as Chicago’s team captain, and then helped guide the American Giants to the first three Negro National League flags (1920-1922).20

It was during the 1925 season that DeMoss, in an unusual situation, saved the first Negro National League from an even earlier demise. Paul DeBono summarized:

“On the morning of the last of the three-game series in Indianapolis, when the American Giants awoke at the boarding house of Frieda Eubanks on the near west side of Indianapolis, Rube Foster did not get up with the rest of the team. Normally Rube was one of the first ones to greet the dawn, and as the morning wore on, the players became concerned at the absence of their fearless leader and began to search the house. Finally, Bingo DeMoss, aided by some of the other players, broke down the bathroom door where they found Rube Foster passed out, lying against the gas heater, his arm badly burned, the odor of natural gas heavy in the air. Rube was rushed to the hospital. Bingo DeMoss placed a long distance call to Sarah Foster and urged her to “come at once if you want to see Rube alive.”21

Foster survived, but would be institutionalized later that year, and died in a sanitarium in 1930.

Following that incident, though, and before leaving the team for medical reasons, Foster engineered DeMoss’ transfer back to Indianapolis, along with that of George Dixon, in large part to reinforce an ABC squad whose roster had been raided by an array of eastern and southern teams.22 DeMoss left Indianapolis after the 1926 season and joined the Detroit Stars. He not only played for the Stars between 1927 and 1930, but managed the team as well. After the 1930 season, Detroit released DeMoss, who hung up his glove and retired as a player.

There remains a debate on whether “Bingo” DeMoss is worthy of enshrinement in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. He made the preliminary ballot for consideration by the 2006 Special Committee On The Negro Leagues, a committee that selected only 17 players from a group of 55, but his case has not been reviewed since.

As statistics from the Negro Leagues are considered somewhat less complete than those kept in “organized” (segregated, non-Black) baseball, it is not necessarily useful to rely only on what has been preserved, as that necessarily omits and ignores all that happened that wasn’t recorded. Modern evaluators are left with the observations of those that saw particular players in action. Dave Malarcher, a tremendous player and manager in his own right, noted that DeMoss “had the courage, confidence, and ability written all over his face and posture. He was the smartest, the coolest, the most errorless ball player I’ve ever seen.”23

Chicago Defender columnist Russ Cowans had watched baseball, Black and White, since before the 1920 establishment of the first Negro National League, and in a 1957 column wrote:

“I was talking to Halley Harding . . . the talk turned to DeMoss, and these are his words about Bingo: “He was without doubt the greatest ball player I’ve ever seen. He was playing second base when I joined the Stars, and his keen knowledge of the game made us the best double-play combination in the Negro National League. He also made me a better shortstop.”24

Cowans added, “But best of all, Bingo was always a gentleman.”25

In short, the consensus has been that “Bingo” DeMoss was fast, a brilliant bunter, and a peerless defender at second base. Eight years earlier, Cowans had asked whether or not Jackie Robinson was “the greatest Negro second sacker of all time?”26 In querying several long-time baseball observers, DeMoss was instead chosen for that honor. It was no hometown choice, as the selected team included Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Cristobal Torriente, John Henry Lloyd, Bill Francis, Ben Taylor, and Satchel Paige.27 On that list, only Francis and DeMoss have not yet been elected to the Hall of Fame.

DeMoss took that “keen” knowledge spoken of by Harding and used it in several managing stints. In 1933, the Columbus Blue Birds folded and were replaced in the league by the Cleveland Giants. That club had been put together “with Bingo DeMoss . . . in charge of the team.”28 He worked at various jobs outside baseball for a few years, and in 1935 his wife, Virgil, passed away. In 1936 he accepted the managerial spot on the Chicago American Giants, replacing Dave Malarcher. In 1937, “Candy” Jim Taylor, a younger brother of his early mentor and manager C.I. Taylor, replaced DeMoss at the Chicago helm. That year “Bingo” was accorded the honor of managing the West team, against Oscar Charleston’s East squad, in the East-West All Star game. DeMoss’ team lost, 10-2, but the reward was in being chosen. It provided a defacto credibility on the old infielder’s ability to manage at the highest levels of professional baseball.

There is not much recorded about DeMoss’ employment after he was fired, but in the 1940 U.S. Census, he listed his occupation as “Ticket seller for a Baseball park” at an annual salary of $480.00. He was living with his brother Willis and five lodgers in a home valued at $3,500. Although Virgil had died in 1935, Elwood was listed on the census as “married.”29 DeMoss’ 1965 obituary observes that he was survived by a wife, Maranda, and two daughters, Bessie Dearborn and Norma Jean Jackson.30

In 1942 and 1943, DeMoss returned to the diamond as manager of the semiprofessional Chicago Brown Bombers,31 and in 1944 was hired by Dr. J. B. Martin to again skipper the American Giants when the former could not reach a contractual agreement with Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe.32 This tour of duty lasted a year as well, and DeMoss’ final managerial shot came in 1945 with Branch Rickey’s United States Baseball League, again managing a team called the Chicago Brown Bombers.33

DeMoss walked away from organized baseball in 1946, but stayed in Chicago for the rest of his life. A popular member of the community, he served as treasurer for the “Old Ball Players Club”,34 a group dedicated to helping old, Black ballplayers that had fallen on hard times financially. On Tuesday, January 26, 1965, at the age of 75 and after what was termed a “long illness,” Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss died at Cook County Hospital in Chicago.35 He was interred at Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois, a final resting place for a number of prominent Black Chicago baseball players, including Jimmie Crutchfield, “Candy” Jim Taylor, Ted Trent, and John Donaldson.

Notes

1 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Pub; 1st edition, April 1, 1994), 228-229.

2 1910 United States Census. Accessed January 30, 2019.

3 Mansfield and Alie DeMoss certificate of marriage. Accessed January 30, 2019.

4 Ancestry.com digitized records. Accessed January 25, 2019.

5 1940 United States Census at Ancestry.com. Accessed February 1, 2019.

6 Justic B. Hill, “Bingo Was His Name,” at MLB.com. Accessed January 30, 2019.

7 There is no evidence that the team existed prior to 1906. An article from the Topeka Daily Capital, dated September 9, 1906, (page 2) discusses how the team wasn’t formed until after 1905.

8 1911 Kansas City Giants team page at Seamheads.com. Accessed January 24, 2019.

9 Riley (1994), 228.

10 2013 Shawnee County Sports Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony — Elwood ‘Bingo’ DeMoss; Online. Accessed: January 31, 2019

11 John B. Holway. Unpublished ms, BINGO, 3; cited in Leslie Heaphy, ed., Black Baseball and Chicago (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland 2006), 64-66.

12 1915 Indianapolis ABCs team page at Seamheads.com.

13 The information is culled from data collected by Larry Lester and accessed on December 28, 2018.

14 A. Monroe, “So They Say: DeMoss, Ballplayers ‘Best’ Choice Dies,” Chicago Defender, February 1, 1965.

15 Indianapolis News, October 25, 1915: 12.

16 “A.B.C. Players Are Fined,” Indianapolis News, December 9, 1915: 2.

17 “Manager Taylor Regrets A.B.C. Trouble,” Chicago Defender, November 6, 1915: 7.

18 Indianapolis News, October 14, 1916: 28.

19 Riley, 489.

20 Negro League Baseball Museum/Kansas State archives, online: Accessed: January 5, 2019.

21 Paul DeBono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., 2006), 54.

22 NLBM/KSU archives, and also corroborated by data gathered by Larry Lester, accessed December 28, 2019.

23 Larry Lester, S. J. Miller, and D. Clark Black Baseball in Chicago (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 66.

24 Russ Cowans, “Russ’ Corner: Old Ball Players To Have Their Day,” Chicago Defender, January 17, 1957: 24.

25 Cowans, “Russ’ Corner: Old Ball Players To Have Their Day.”

26 Cowans, “Russ’ Corner,” Chicago Defender, July 23, 1949: 15.

27 Cowans, “Russ’ Corner,” 1949.

28 “Columbus Drops Out of the League and Cleveland Gets Its Berth,” Chicago Defender, August 26, 1933: 8.

29 1940 United States Census. Online at Ancestry.com, accessed February 1, 2019.

30 “Old Baseball Great ‘Bingo’ DeMoss Dies,’ Chicago Daily Defender, January 27, 1965: 25.

31 “Brown Bombers Leave Today For Training Camp,” Chicago Tribune, April 5, 1942: 27, and “Leading Negro Nines Play 2 Games Today,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1943: 35.

32 DeBono, 165.

33 Lester, Miller, and Clark, Black Baseball in Chicago, 66.

34 Cowans. “Old Ball Players To Have Their Day.” 24, as well as uncredited articles “Old Ball Players Set Date for Installation,” Chicago Defender, March 7, 1964: 14; and “Old Ballplayers Honor Williams,” Chicago Defender, January 15, 1966: 17.

35 “Old Baseball Great ‘Bingo’ DeMoss Dies,” Chicago Defender, January 27, 1965.

Full Name

Elwood DeMoss

Born

September 5, 1889 at Topeka, KS (US)

Died

January 26, 1965 at Chicago, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.