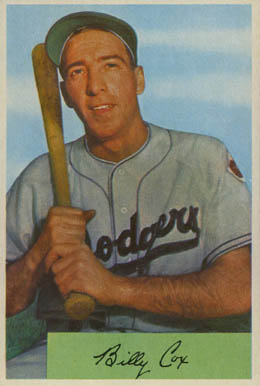

Billy Cox

Imagine an infielder who played his last game more than half a century ago, who appeared in 1,058 games and batted .262 lifetime. Probably only his family and his most diehard fans would know his name. But that’s not so in the case of William Richard “Billy” Cox. Anchoring the infield on three Brooklyn pennant winners assured Cox of lasting fame — but his immortality was guaranteed when Roger Kahn featured him along with many of his teammates in The Boys of Summer, one of the most enduring baseball books of the 20th century.

Imagine an infielder who played his last game more than half a century ago, who appeared in 1,058 games and batted .262 lifetime. Probably only his family and his most diehard fans would know his name. But that’s not so in the case of William Richard “Billy” Cox. Anchoring the infield on three Brooklyn pennant winners assured Cox of lasting fame — but his immortality was guaranteed when Roger Kahn featured him along with many of his teammates in The Boys of Summer, one of the most enduring baseball books of the 20th century.

During his time with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Cox was hailed by many of his contemporaries as the finest fielding third baseman of his era. “He’s not a third baseman, he’s a blankety-blank acrobat,” Casey Stengel said after witnessing Cox in action in the World Series.1 And after seeing Cox’s steady glove and powerful arm in the 1952 Fall Classic, future Hall of Fame third baseman George Kell declared, “I never dreamed third base could be played with such artistry until I saw Cox in that series.”2

When the Dodgers sold Cox to Baltimore in 1954, owner Walter O’Malley said, “We regard Cox as the greatest glove man we have ever had.”3 Teammate Carl Erskine had this to say: “There’s never been anybody with quicker hands than Billy Cox.”4

Cox was born August 29, 1919, in the central Pennsylvania town of Newport, an industrial community situated alongside the Juniata River. The town’s population was just under 2,000 at the time of his birth. Cox was part of a family of nine, including two brothers and four sisters. Billy’s mother, the former Mary Toomey, died at age 32; Billy had turned eight years old just a few days earlier. Cox’s father, Fred, worked in the local tannery (one of the town’s largest employers) and played semi-pro ball. His son showed a passion for the game early. Billy recalled playing with other local children at about age seven, using a broomstick and tennis ball.

One Newporter who spoke with Roger Kahn remembered Cox standing by the local railroad tracks. “If there was nobody to play with, he’d pick up stones and hit ’em with a stick,” Jack Heisey said. “When he was ten, he fielded like a man.”5

Billy’s childhood was a difficult one. His widowed father struggled to make ends meet for his large family. Things got especially difficult during the Great Depression when the tannery closed, but Fred Cox found employment through the federal Works Progress Administration and later worked for the state highway department.

The younger Cox starred on the Newport High School baseball team, which won 21 of 24 games his last two years. After his graduation he played semi-pro ball. The independent Newport club played strong competition from the Pennsylvania coal and steel regions.

Cox’s first shot at professional baseball came in 1938, when a Pirates scout convinced the team to send him to their Class D club at Valdosta, Georgia for a tryout. “He didn’t have no clothes. I ran the town collection,” Heisey told Kahn. ”We gave him clothing and a send off. (But) a month later he come home. He got too goddamn lonely.”6 The Pirates scout, John Brackenridge, said later that Cox was impressive in the audition, but he became homesick overnight and returned home before he could sign a contract. The Pirates forgot about him, but Brackenridge did not. He tried to interest the Phillies in his services, and when they passed, Brackenridge got his name on a contract for Harrisburg, which had reentered the Class B Interstate League for 1940 as an independent club after having dropped out following the 1935 season.

The 20-year-old batted a solid .288 in his first campaign with the Harrisburg Senators. With a year’s seasoning, he tore up the league the next summer, winning the batting title with a .363 average, 27 points higher than the runner-up. He also had a 22-game hitting streak; led the league in hits, doubles and total bases; and set a league record for most assists by a shortstop. His performance that summer drew the attention of recently-retired Pittsburgh third baseman Pie Traynor, who was scouting for the Bucs.

Harrisburg manager Lester Bell, a former Cardinal third baseman, had several conversations with Traynor about Cox. Bell said, “He seems to have it. Looks like a kid who could go into the majors on one bounce.”7 Traynor responded, “Yes, he’s a great prospect, but your club is asking a lot of money for a Class B player.”8 But once other clubs started showing interest, the Pirates were ready to make a deal. In August 1941 they agreed to pay $20,000, reported at the time to be one of the largest sums ever paid for a player at that level, for Cox’s services.

Cox’s time in Harrisburg was memorable for another reason: he met his future wife, Anna Radle. Her father was a baseball fan who regularly took her to Senators’ games. Details of their courtship have been lost to memory, but Cox’s eldest daughter is reasonably certain her mother was the one pursuing the taciturn shortstop.

During a September call-up to Forbes Field, Cox managed a .270 average and turned eight double plays in a ten-game trial during which he was auditioning to be Arky Vaughan’s successor. Vaughan moved over to third base, and manager Frank Frisch said he expected this lineup to continue into the next season. Pirates President Bill Benswanger said Cox looked like the best Pirates shortstop since Glenn Wright. “Every baseball man I’ve talked to says the boy simply can’t miss.”9

But Billy’s life and career took a detour, as did millions of other young men’s, when the United States entered World War II a few months later.

The Sporting News reported that Cox received a 1-A rating from his draft board and passed his Army physical on January 14. The paper said he had been staying in shape by playing basketball with a local team, and had scored 19 points in a recent game. Cox was inducted into the Army on February 9, 1942, and was initially stationed at the New Cumberland Reception Center, just outside Harrisburg, where he was able to play for an army team. During the war years, the center would process approximately half a million Pennsylvanians who entered the service.

With Cox on hand, the base commander looked forward to a successful baseball team. In late May, the paper reported Cox had received special permission from the Army to play in an exhibition game between Harrisburg and the Pirates. Cox had a hit and two walks against his former teammates, and the paper said his presence in the lineup was a big reason the game drew 3,500 fans.

In June of 1943 Cox headed overseas as a member of the 814th Signal Corps. The Signal Corps followed right behind front-line Army troops in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. Cox and his fellow soldiers were tasked with laying wire and setting up communication centers for the advancing troops, which put them in the thick of the action. He had little opportunity to pick up a glove and bat in Europe, though he did play for an Army All-Star team against Navy All-Stars in Sicily in August, 1944.

Corporal Billy Cox was discharged from the Army on November 14, 1945. He married Anna Radle 12 days later.

When Cox showed up for spring training in 1946, he found himself in the spotlight. Manager Frisch declared: “We have a couple of the hottest youngsters in baseball today in shortstop Billy Cox and outfielder Ralph Kiner.”10

Pirates coach and Hall of Fame shortstop Honus Wagner watched his latest successor with approval, telling writer Fred Lieb, “He moves around pretty nice, doesn’t he? I think I’ve given him a few pointers.”11 Cox credited both Wagner and Frisch with helping him learn the position.

Cox was grateful to be home and to have the opportunity to resume his baseball career. Although he had lost four prime years, he said, “I’m not kicking. I went through four years of the war, and came out whole, so I guess I am lucky.”12 Cox may not have suffered physical wounds, but his malaria flared up several times during his career. He never carried more than 150 pounds on his lean 5-foot, 10-inch frame, and his weight would sometimes drop into the 130s amid a recurrence of the illness, leaving him looking emaciated. His teammates sometimes called him “Horse” or “Hoss” because of his long, narrow face.

Before the war, Pirates officials expressed hope that Cox could gain 20 pounds as he matured. His struggles to maintain his weight left him injury-prone; he appeared in more than 132 games in a season only once and surpassed 500 plate appearances just twice.

He also carried emotional scars. But like so many men of his generation, he did his best to repress them. Harold Burr of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote about one incident, though, when the Pirates were playing in Boston, and a ballpark fireworks display sent Cox plunging for cover in the dugout.13 The roar of the crowd could also trigger a moment of terror. Cox told his teammates he was never wounded in action, though his helmet was once blown off by an explosion.

Cox’s glove was the foundation of his fame, but he showed surprising power at times for someone so slightly built. On August 16, 1947, he slammed two home runs in a game in which the Pirates hit ten overall. Teammate Ralph Kiner hit three while Hank Greenberg also had two. It was the first time in major league history that three teammates had two or more home runs in the same game.

Just when it looked like Cox had found a home in Pittsburgh, he was packaged with his friend, pitcher Preacher Roe, in a trade to Brooklyn. The deal, made on December 8, 1947, is often called the best in Dodgers history. The Dodgers sent Dixie Walker, Hal Gregg, and Vic Lombardi to the Pirates for Roe, Cox, and Gene Mauch. Walker, who had starred in right field for Brooklyn for nine seasons, had become expendable at the beginning of the year because of his role in a petition opposing the promotion of Jackie Robinson to the major leagues.

Cox was moving from a club that had finished eighth and seventh in his two seasons with them to the defending pennant winners. However, despite their recent success the 1948 Dodgers would be a team in transition. During spring training, Branch Rickey unloaded starting second baseman Eddie Stanky in a deal with the Boston Braves, allowing Jackie Robinson to move to second, where he had played in Montreal. Gil Hodges began to stake his claim to first base. The only 1947 infield starter assured of his job was the shortstop, Dodger captain Pee Wee Reese. All this left Cox to battle incumbent Spider Jorgensen for the third base job.

Cox’s fight to win the position in 1948 set a pattern that was to remain consistent throughout his Brooklyn tenure. There was never a shortage of hopefuls for third. At different times Jorgensen, Eddie Miksis, Bobby Morgan, and Rocky Bridges were among those expected to dislodge Cox, but Cox always emerged as the regular at some point during the season.

Cox wore a tiny, three-fingered black Whelan glove that he took off and put back on before every pitch. When his roomie was pitching, Cox reassured Roe: “Old Hoss has got ’em” or “Let ’em hit it to old Hoss, Preach. I’ll snip it for ya.”14

After his retirement from the game, Roe admitted to throwing a spitball. Part of Roe’s routine to keep the spitter from being discovered involved his roommate; if a suspicious umpire asked to examine the ball, Roe would toss it to Cox, who would then roll it in to the umpire. By then, of course, any traces of the Beech-Nut gum Roe used to moisten it were long gone. Yet Cox wasn’t beyond bedeviling his friend when the mood struck him; on routine grounders he would hold onto the ball seemingly forever before firing it to Hodges at first. He trusted his arm and his knowledge of the runner’s speed.

Duke Snider said that on hard-hit balls, Cox would “flick that little glove like a serpent’s tongue and snatch the hot shot. Then he’d hold the ball and look at it, as if he were counting the stitches, and then he’d gun the ball to first base and just nip the runner by half a step.”15 A fan remembered a member of the Dodger announcing team describing Cox’s hesitation with the ball: “He checks to see if it’s broken, and throws to first for the out.”16 Reese would shout, “Throw the damn ball, Billy.”17 In the postgame clubhouse Roe would grumble at his friend.

Erskine admired Cox’s bravery in playing in on hitters, something particularly dangerous for a third baseman who would be vulnerable to injury from a hard smash. “‘We said, ‘Get back, Billy,’” Erskine recalled.18 Yet Cox held his ground, and as a result he could pick off line drives that would get by an average third sacker.

Cox’s legendary glove skills briefly deserted him in the eighth inning of an August 6, 1949 against the Reds in Cincinnati, when he tied a National League record by making three errors in one inning. He started off with a rare high throw to Hodges at first, then fumbled a grounder on a force play, then dropped another throw for a force.

Ironically for someone who made his reputation with his glove, Cox was a victim of one of Willie Mays’ finest catches. The Dodgers were playing at the Polo Grounds on August 15, 1951, and Cox was the runner at third with one out in the top of the eighth inning. The game was a 1-1 tie. Carl Furillo hit a hard liner to right center that looked like a sure extra-base hit. Carl Erskine and the rest of the Dodgers watched in disbelief as Mays made a diving catch, rolled, sprang to his feet and threw blindly toward home, which was 350 feet away. It was a perfect strike. Erskine remembered: “Cox, who had tagged, was such an easy out that he didn’t even bother sliding. He just stared in disbelief as Wes Westrum tagged him to complete the astonishing double play.”19

There’s little doubt that Cox was grateful that he and Roe had come over together from the Pirates. The pair roomed together throughout their time in Brooklyn. In his memoir, Roe recalled that Cox was self-conscious about his comparatively poor education, but the two shared a passion for crossword puzzles. “He would take them and do all the three and four-letter words in the book then pass it on to me to finish. I got to where I had to have two books going at one time because he was always in the one I had started.”20

Cox did build friendships with other Dodgers. Duke Snider remembered: “Billy and I got to be good friends after we became teammates, but it didn’t start out that way. When he was with the Pirates, he got a hit to center field one day and tried to stretch it into a double. I threw to second base, and the ball hit him on the head. They had to carry him off the field.”21

Snider recalled that Roe and Cox were avid poker players, and he remembered one lengthy game where, out of cash, Cox wrote a $200 check and dropped it into the pot. As soon as Cox won the hand, he tore up the check, saying, “If my wife had seen a cancelled check for that much money, she would have killed me.”22

Cox earned the appreciation of his teammates for his range and strong, accurate arm. Erskine said, “He had such quick hands that it seemed as though he had four gloves instead of one.”23 Clem Labine said Cox had the arms of a blacksmith.

Before Cox put on Dodger blue the team had fallen to the Yankees in two World Series (1941 and 1947). They lost to the Bronx Bombers three more times during his tenure (1949, 1952, and 1953). Cox, however, didn’t have to shoulder the blame for those defeats. He batted a combined .302 in the three Fall Classics. He saved his best offensive performance for last, leading the Dodgers with six RBIs in as many games in the 1953 series, knocking out three doubles and a home run.

Despite these heroics, Cox always had to battle to hold onto his job. The Dodgers had 11 potential third basemen in camp one year thanks to their huge farm system. The situation flared into controversy in the spring of 1953. Manager Charlie Dressen, wanting to bring rookie second baseman Jim Gilliam into the everyday lineup, decided to move Jackie Robinson over to third, leaving Cox a utility man. Dressen announced the move to reporters but never spoke directly to Cox, angering him and wounding his pride. Roger Kahn began a story in the New York Herald Tribune: “While Charlie Dressen fiddles with his infield, Billy Cox burns.”24

The controversy faded; Robinson proved to be more comfortable in left field than at third base, and Cox still got into 100 games. He batted .291, the highest single-season average of his career. He also set a Dodger single-season record for the highest fielding average by a third baseman, .974.

The Dodger squad won 105 games, but Dressen’s own bid for a multi-year contract led to his postseason departure, and Walter Alston was promoted from Montreal to take over as manager.

After a disappointing second-place finish in 1954, the Dodgers embarked on a youth movement. One outcome was that, seven years after Cox and Roe arrived in Brooklyn together, they departed together. The Dodgers sold Cox, 34, and Roe, 38, to the Baltimore Orioles on December 13 for a reported $60,000 in cash. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that it was no secret that neither player got along with rookie manager Alston. In addition, Cox was frustrated over being reduced to part-time status. Unloading the veterans also opened space on the major-league roster to allow the signing of bonus baby Sandy Koufax the day after the deal was made.

Roe retired instead of going to Baltimore — but Cox pronounced himself happy to have the opportunity to play regularly. He told The Sporting News he harbored no hard feelings toward the Dodgers.25

Cox won a regular job in his first American League season, and while his steady glove work continued, the spark in his bat was gone. After the first 53 games of the 1955 season, he was batting a career-low .211 and the Orioles were mired in last place with a 17-37 record, 20 games behind the league-leading Yankees.

An opportunity for a fresh start arrived at the June 15 trading deadline, but instead Cox walked away from the game. Cleveland was the defending American League champion, but the Indians were struggling in third place and made a deal to acquire Cox and outfielder Gene Woodling in exchange for Dave Pope and Wally Westlake. Cleveland General Manager Hank Greenberg thought the two veterans could help them in their quest to overtake the Yankees, who had reclaimed their familiar spot atop the standings. But Cox stunned the Tribe by announcing that he was considering retirement.

Even a personal plea from manager Al Lopez couldn’t sway Cox. He told Lopez, “I know you and Hank and I like you both. I don’t want to fool you or myself. My leg is bad. It buckled under me the other day.”26 When the pleas continued, Cox finally admitted something he had been hiding from everyone, including Orioles manager and GM Paul Richards and his wife: he was also suffering from a hernia in his groin that would require surgical repair. Cleveland relented, accepting a cash settlement in lieu of Cox’s services on June 22. Cox went home, showed friends his swollen and battered legs, and said goodbye to the game he had loved for so long.

After the 1957 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers fled to California, but the bonds among the Boys of Summer remained. Cox’s son-in-law recalls Roe and George “Shotgun” Shuba joining Billy on a post-retirement deer hunting trip.

Although Cox largely stayed away from the spotlight, his reputation endured in the game. Years after Cox’s retirement, Casey Stengel greeted Brooks Robinson during spring training as the second-best third baseman he’d ever seen. When Robinson asked who the best was, Stengel answered: “Number three, over there in Brooklyn.”27 And when a statue of Robinson was unveiled at Camden Yards in 2012, Robinson told the Baltimore Sun that he was sorry he never got to meet Cox in person; he was signed the same summer Cox retired, and the former Dodger was one of only four or five men to wear the Orioles uniform whom Robinson never met.

According to his surviving family members, Cox had no interest in a post-playing job in baseball. He had an offer to put his name on a Brooklyn restaurant, but that didn’t appeal to him. He was part-owner of a gas station in Harrisburg for a time, and then spent the rest of his life tending bar at a variety of places in Newport. He and Anna raised three children (two daughters, Shawn and Cindy, and a son, Billy Jr.), and Anna taught at local schools. Cox was working at a local private club, the Owls, when Roger Kahn found him.

It took some prodding on Kahn’s part to get Cox reminiscing, but once he did, his memories took him back to his days alongside his friend the Preacher. “Hey, there was this day Preach was pitching. I put on a catcher’s mask and shin guards and a chest protector and I said, ‘Okay, I’m ready.’ Preach said, ‘wear anything you want, long as you’re there.’ It wasn’t trouble to make the joke. Campy [Roy Campanella]’s locker was right near mine.’”28

Like Gil Hodges and so many other men who served in World War II, Cox had become a smoker while overseas. Although he had kicked the habit years earlier, the cigarettes took their toll, and he contracted esophageal cancer. Billy Cox died at a Harrisburg hospital on March 30, 1978. He was 58 years old.

When Preacher Roe heard from a teammate that Cox had passed away, he phoned Anna Cox, asking why she hadn’t let him know. She told him that he was the one person Billy didn’t want to see the ravages his illness had worked on his body.29

Billy Cox was laid to rest in his hometown, and his name lives on there. Newport’s youth baseball complex, which is on the site where the tannery that employed his father once stood, is known as Billy Cox Field.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Joe DeSantis and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Interviews

Cox family members, December 2016

Carl Erskine, January 2017

Newspapers

The Sporting News

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

The New York Times

The Baltimore Sun

The Harrisburg Telegraph

Internet resources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-fever.com

Bedingfield, Gary: Baseball in Wartime http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/cox_billy.htm

Uhlman, Harold: “Ole Hoss Has Got ’Em.” Think Blue LA. http://www.thinkbluela.com/2016/12/billy-cox-ole-hoss-has-got-em/

Books

Carl Erskine, Tales From the Dodgers Dugout, New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004

Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer. New York: Harper and Row, 1972.

Andrew Paul Mele, Tearin’ Up the Pea Patch, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2015.

William McNeil, The Dodgers Encyclopedia, New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003.

Preacher Roe and Sarah Preslar, Sarah, When Baseball Was Still a Game, Hardy, Arkansas: Catalyst Apex Publishing, 2005.

Duke Snider and Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen: Defining Dodger Greatness Across Eras, Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006.

Notes

1 Duke Snider and Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen: Defining Dodger Greatness Across Eras, Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006: 71.

2 John S. Radosta, “Billy Cox, 58, a Dodger Standout as Third Baseman in Early 50’s,” The New York Times, April 1, 1978.

3 Dave Anderson, “Baltimore Shells Out $60,000 for Cox and Roe,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1954, 18.

4 Carl Erskine, telephone interview, January 2017 (hereafter Erskine interview).

5 Roger Kahn, The Boys of Summer, New York: Harper and Row, 1972: 418.

6 Ibid., 419.

7 Frederick G. Lieb, “‘Can’t Miss’ Cox Back as Bucco after Missing Four Campaigns,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1946, 7.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Harold C. Burr, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 26, 1954.

14 Harold Uhlman, “Old Hoss Has Got ’Em.” Think Blue LA, http://www.thinkbluela.com/2016/12/billy-cox-ole-hoss-has-got-em/, accessed December 12, 2016.

15 Snider and Pepe, Few and Chosen, 72.

16 Baseball-fever.com, “Billy Cox,” March 31, 2011.

17 Andrew Paul Mele, Tearin’ Up the Pea Patch, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2015: 106

18 Erskine interview.

19 Carl Erskine, Tales From the Dodger Dugout , New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004: 62.

20 Preacher Roe and Sarah Preslar, When Baseball Was Still a Game, Hardy, Arkansas: Catalyst Apex Publishing, 2005.

21 Snider and Phil Pepe, Few and Chosen, 72.

22 Ibid.

23 Erskine, Tales From the Dodger Dugout, 37.

24 Kahn, The Boys of Summer, 420

25 Hugh Trader, “‘Faster Than Turley’ Tag on Orioles’ Rookie Moore,” The Sporting News, February 23, 1955, 17.

26 Hal Lebovitz, “Pope, Woodling Swapped, but Cox Talks of Quitting,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1955, 9.

27 Uhlman, “Old Hoss Has Got ’Em.”

28 Kahn, The Boys of Summer, 420.

29 Roe and Presslar, When Baseball Was Still a Game.

Full Name

William Richard Cox

Born

August 29, 1919 at Newport, PA (USA)

Died

March 30, 1978 at Harrisburg, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.