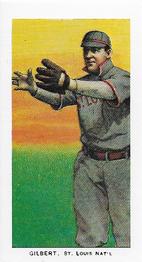

Billy Gilbert

How do you work through tragedy? Billy Gilbert, a man often praised for his work ethic,1 likely dealt with it by getting back to what he knew best: putting his nose to the grindstone in the familiar routine of baseball. On April 23, 1904, in front of one of the largest crowds at the Polo Grounds that season, the second baseman rejoined the New York Giants after a week’s absence due to a death in the family. He went 2-for-3 with a double, an RBI, and a stolen base. Gilbert also cleanly handled all six of his chances in the field. The Giants were up, 10-0, through six innings and cruised to a blowout win against the Phillies. Late in the game, Giants manager John McGraw — Gilbert’s manager for five straight seasons — pinch-hit for Billy. Maybe it was a strategic move. But perhaps it was McGraw’s way of saying, “You’ve had a terrible week. Welcome back and let’s call it a day.”

How do you work through tragedy? Billy Gilbert, a man often praised for his work ethic,1 likely dealt with it by getting back to what he knew best: putting his nose to the grindstone in the familiar routine of baseball. On April 23, 1904, in front of one of the largest crowds at the Polo Grounds that season, the second baseman rejoined the New York Giants after a week’s absence due to a death in the family. He went 2-for-3 with a double, an RBI, and a stolen base. Gilbert also cleanly handled all six of his chances in the field. The Giants were up, 10-0, through six innings and cruised to a blowout win against the Phillies. Late in the game, Giants manager John McGraw — Gilbert’s manager for five straight seasons — pinch-hit for Billy. Maybe it was a strategic move. But perhaps it was McGraw’s way of saying, “You’ve had a terrible week. Welcome back and let’s call it a day.”

Six days prior, Annie Gough Gilbert, Billy’s wife of six years, had passed away in their hometown of Trenton, New Jersey.2 The Trenton Times gave no cause of death in her obituary.3 Despite his loss, Gilbert’s two-hit game against Philadelphia started the first of his 140 straight appearances for New York that season. The undersized infielder — Gilbert was listed as 5-feet-4 and 153 pounds — did not get a day off until late September, long after the Giants juggernaut had clinched the National League pennant.

Many popular sources list William Oliver Gilbert’s birthdate as June 21, 1876, in Tullytown, Pennsylvania. Yet U.S. Census Records show Billy’s birth year as 1875. Billy was the second of four children born to Charles and Anna Gilbert (née Dunham). He had an older brother, Alpheus, and two younger sisters named Clara and Sadie.4 By the time Billy was a toddler, his father, a wheelwright, had moved the family to the larger town of Langhorne, Pennsylvania.5 Sometime in Gilbert’s childhood and by 1894 at the latest, the family moved across the Delaware River from Lower Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to Trenton, New Jersey.6 The loss of Annie was not the only tragedy that the second baseman had to face: the 1900 Census shows that of eight children in the Gilbert family, only two others besides Billy had survived.7

A city whose motto is “Trenton Makes, the World Takes” had plenty of industrial plants in the late 19th century. This, in turn, fueled a very competitive Trades Baseball League. The League ran from 1887 to 1895, with factory teams playing three games a week. Trade league play was supplemented by Trenton’s YMCA circuit, which lasted from 1895 to 1905 and “resulted in the development of one of the strongest semi-professional teams in the United States, according to the judgment of visiting experts.”8 Since both Charles and Alpheus Gilbert were tradesmen, it is likely that young Billy followed in their footsteps and played in the Trades League. He certainly played in the YMCA League and used it as a springboard to professional baseball.

Gilbert made his professional debut in 1897 with the Fall River Indians of the Class B New England League.9 There Gilbert teamed with former New York Giants star Roger Connor, who was winding down his professional career close to the latter’s Waterbury, Connecticut, home. Gilbert logged 50 games, batted just .210, but legged out extra-base hits in nearly one-third of his knocks.

Gilbert spent his next two seasons in the Class C New York State League. He split time between the Palmyra and Lyons clubs in 1898 and became a member of the Utica Pent-Ups in 1899. On a very good (70-43) Utica ballclub, the speedster 10 distinguished himself by stealing 78 bases, batting .300, and hitting ten triples to rank among NYSL leaders.11 That performance was good enough for Gilbert to be drafted by the Milwaukee Brewers of the Western League — soon to be renamed the American League — and farmed out to Class A Syracuse for the 1900 season.12

Perhaps the Eastern League’s 1900 Syracuse Stars kept it loose in the clubhouse — their leading pitcher, Nick Altrock, later teamed with Al Schacht as part of the “Clown Prince of Baseball” comedy routine. Nonetheless, there was little that year for the dreadful Stars to laugh about. They finished 44-84, dead last in the EL. But Gilbert was a bright spot. He led the team with 77 runs, and his 45 steals were fifth in the league.

In 1901, Gilbert went back to Milwaukee and played second base for the Brewers in the American League’s inaugural year.13 The team’s performance on Opening Day was memorable for all the wrong reasons: the Brewers, who led 13-3 midway through the eighth, blew the lead and fell to host Detroit, 14-13,14 in the biggest Opening Day collapse in history.

For the second year in a row, Gilbert was a rare highlight on a dreadful team. Skipper Hugh Duffy’s squad lost their first five games en route to a 48-89 finish. Nonetheless, the rookie set career highs in average (.270), extra-base hits (21), and slugging percentage (.327). His .936 fielding percentage was in line with other American League second basemen. Gilbert led Milwaukee in sacrifice hits.

Gilbert’s partnership with McGraw began the next season, at the beginning of 1902, when McGraw “bought Gilbert’s release from the Milwaukee team and assigned him” to Baltimore. 15 Like the 5’7” “Little Napoleon,” Gilbert was a small, hard-working infielder. Gilbert’s old club was moving on too. Milwaukee relocated to St. Louis in 1902 to become the Browns.

Playing shortstop for the only time in his career, Gilbert committed a brutal 78 errors in 129 games for Baltimore. Yet offensively, he hit .245, slammed two of his four career homers, and led the Orioles in both steals (38) and sacrifice hits (20). In what was becoming a theme, Gilbert shone on a last place ball club. The ’02 Orioles dropped 43 of their final 56 games.

Gilbert’s Orioles were a respectable 26-29 after a June 26 win over Philadelphia when the wheels started to come off the franchise. McGraw, sitting out a 15-day suspension for abuse of an umpire, covertly accepted the general managership of the New York Giants. When McGraw returned, he demanded and received his release from the Orioles as an alternative for cash-strapped Baltimore’s inability to pay McGraw an IOU. Baltimore’s cash situation was so bad that Oriole owners were forced to sell their stock to interests controlled by Giants owner Andrew Freedman. 16

Bill Lamb writes:

“As Ban Johnson watched helplessly, his enemy Freedman set about dismantling the Orioles, granting the team’s star players their unconditional release. Joe McGinnity, Roger Bresnahan, Dan McGann, and Jack Cronin seized the opportunity presented, leaving the Orioles to sign with the N.Y. Giants… The rapid departure of so many players had left the Orioles without the manpower needed for a game against the Browns and obliged to forfeit. That forfeit triggered a clause in the American League Constitution that empowered A.L. President Ban Johnson to strip the Baltimore club from delinquent owner Freedman and place the Orioles in A.L. receivership. Using players contributed from other A.L. clubs, Johnson then cobbled together the roster needed for Baltimore to complete the 1902 season.”17

His poor fielding percentage aside, Gilbert impressed McGraw enough to be part of the exodus from Charm City to the Big Apple.18 While the 1902 Giants struggled as badly as their Oriole counterparts, a loaded 1903 version finished 84-55, second to Honus Wagner’s Pittsburgh Pirates in the race for the National League pennant. A 7-4 win at Philadelphia on June 17 put New York temporarily in first place. But returning home to Coogan’s Bluff did not do them any favors: the Giants closed June losing six of eight while the Pirates rattled off a 14-game win streak. Pittsburgh consistently kept the Giants at arm’s-length for the rest of the season even though the Pirates lost to the Boston Americans, five games to three, in that October’s first modern World Series.

Gilbert hit .252 and had a .348 on-base percentage (OBP) as the Giants everyday second baseman in 1903. For the second straight year, he ranked in his league’s top ten in steals (37), sacrifice hits (26), and times hit-by-pitch (20). His .935 fielding percentage was in line with league second basemen. It was the last full season he fielded below .940.

While 1904 was a devastating year for Gilbert personally due to the loss of his wife, it was a banner year for his baseball team. The Giants, Cubs, and Reds were all bunched together at the top of the National League standings on the morning of June 15. But while New York and Chicago both lost only one game that day, the Reds lost two. The Giants quickly and decisively put the rest of the National League in their rearview mirror. Starting with a 4-3 win over the Cardinals on the 16th, in which Gilbert had an RBI double, McGraw’s charges rang off 18 wins in a row to take a commanding hold of first place, which they would never relinquish. Gilbert hit a blistering .364 with 13 steals and 14 RBI in 74 at-bats during the streak. He struck out only three times.

But despite clinching the pennant, there was no World Series for the Giants in 1904. The Giants refused to give any sort of spotlight to the rival and perceived “inferior” American League.19 20

New York’s first World Series came in 1905. The Giants did not lead from wire-to-wire that season, but after a 5-4 win at Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl on April 24, in which Gilbert singled and scored a run, New York improved to 5-1 and climbed into first plac

Gilbert started the 1905 season by playing some of his best offensive baseball. He batted .329 (23-for-70) in New York’s first 19 games, scoring 20 runs and walking nine times. The Giants, who began the year 21-5, finished the season with an impressive 105-48 record. New York had the National League’s most potent offense, and behind aces McGinnity and Christy Mathewson, one of the best pitching staffs. Gilbert contributed significantly, recording both a .331 OBP and his best fielding percentage as a Giant. Gilbert missed nearly five weeks of action in August and September but returned to the lineup on September 22. He had been playing great baseball just before his injury, batting .571 with a pair of walks in the four games before getting hurt. In his place, McGraw inserted Sammy Strang, an excellent role player, but Strang struggled as a regular and hit just .167 in his 29 starts.

Gilbert was healthy by the time the World Series started on October 9. He had an excellent post-season, hitting .294 to rank second on New York, tied for the Giants’ lead in hits (5), and played errorless defense in New York’s four-games-to- one victory over the Philadelphia Athletics in a World Series dominated by pitching. (All five games were shutouts). Facing future Hall of Famer Eddie Plank with two out in the bottom of the fourth inning of Game Four, Gilbert singled home Sam Mertes for the only run of the game. Gilbert ended the sixth inning by assisting on Danny Murphy’s ground out to help preserve McGinnity’s shutout.

The next day in Game Five, Gilbert drove in Mertes again with the winning run, this time on a fifth-inning sacrifice fly, to give the Giants a 1-0 lead. Defensively, the busy Gilbert handled eight chances cleanly, recording five assists and three putouts, to preserve Christy Mathewson’s 2-0 shutout and, more importantly, give the Giants the World Series title. Gilbert deservedly received praise for his batting prowess during the Series. But perhaps more importantly, he had recorded nine putouts and 15 assists, handling every chance cleanly.

However, 1906 was an up and down year for Gilbert. He got off to a dreadful start — batting .152 in his first 11 games. Yet after getting eight hits in a five-game series at Boston, Gilbert’s batting average soared to .288. Off the diamond, Gilbert married Blanche Morrison, ten years his junior, on June 25 in Manhattan.21 Amazingly by modern standards, Gilbert played on his wedding day – a Monday 12-3 pasting of the Phillies. But in mid-July, Gilbert went into a bad slump, and by mid-August, he was benched for the hot-hitting Strang when it was clear that New York was out of pennant contention.22 Gilbert’s last game as a Giant was as a defensive replacement in a September 24 loss to the eventual pennant-winning Cubs.

Billy Gilbert was released by the team in January 1907. “Gilbert enjoys the distinction of being one of the best behaved and most popular of New York players, but he deteriorated so much in batting last year that McGraw concluded that if the team was ever to get the championship back its batting power must be improved,” wrote the New York Times. “He was loath to consider a proposition to part with Gilbert, who, according to the Giants leader, is one of the best fielding second basemen in the country.”23 But New York’s offseason acquisition of Reds second baseman Tommy Corcoran sealed Gilbert’s fate.

“A year ago, he was considered second only to (Nap) Lajoie as a second baseman,” the New London (Connecticut) Day reported of Gilbert soon after his release. “Never a strong hitter, he furnished the surprise of the world’s series of 1905 by outhitting any player on either team.”24 Gilbert’s age, his inability to “rid himself of superfluous flesh,” and his “pronounced slump” led to the move, it concluded.25 “He attended to his own business on the field and acted the part of a gentleman elsewhere,” the Day continued. “Seldom has there been a more popular ball player. He has thousands of friends in New York for he usually winters here.”26 The article mentioned that Gilbert had announced his “permanent retirement” and that he would run a café in which he had a partial interest.27 But evidently, the café would have to wait. Gilbert found himself playing the 1907 season back home, suiting up for the Class B Trenton Tigers of the Tri-State League. He batted .226 as the Tigers’ everyday second baseman. Trenton must have pitched, not hit, their way to a respectable 70-54 mark because Gilbert’s 13 extra-base hits ranked fourth on the team. 28

Gilbert returned to the big leagues and served as the St. Louis Cardinals’ Opening Day second baseman in 1908. He reached base in 11 of his first 15 Cardinal games, achieving an OBP as high as .405 after a May 3 loss to the Cubs. But St. Louis, already 3-12 at that point, would only get worse and Gilbert did little to stop the team’s slide, finishing with a .214 batting average on a team that finished 50 games out of first place. His six steals and eight sacrifice hits were far and away career lows of his seven full big league seasons. For most of 1908, Gilbert started at second base, but after the Cards were swept at Boston in an August 8 doubleheader, manager John McCloskey inserted Chappy Charles at second for the rest of the season.

Multiple media outlets in the fall of 1908 reported that Gilbert would manage the St. Louis Cardinals.29 Instead, St. Louis hired Gilbert’s former Giant teammate Roger Bresnahan to skipper the Cards for 1909. Gilbert played in 12 games under Bresnahan, with 11 of them coming in June.

Gilbert’s June 11 performance was disappointing — he went 0-for-3 in a shutout loss to the Phillies. But that same day, Blanche gave birth to his only child: a daughter named Althea.30 In his final big league game on June 27, Gilbert singled off Hall of Famer Vic Willis. By August, the Redbirds had moved Gilbert from player to scout He remained with the club “scouring the country for likely-looking young ball tossers” for the rest of the season.31

But Gilbert still had three more seasons of professional baseball left in him. He batted .216 in 63 games for the Class B Albany Senators in 1910. For the next two seasons, he was a player-manager for the Erie Sailors, who played in the Class C Ohio-Pennsylvania League in 1911 and jumped to the Class B Central League in 1912. “After observing the work done in practice, I can truthfully say that I do not fear the majority of our rivals,” Gilbert told the Mansfield (Ohio) Shield in April 1911, even though he was inheriting a 55-69 ballclub from the 1910 campaign. “Erie is going to finish in the first division if hard work and fast play count for anything.” 32

Gilbert’s team fulfilled his expectations. The Sailors went 152-109 during the two seasons, finishing third in their league during both summers. Although he was now in his mid-30s, Gilbert still hit .249 with 21 steals and a team-leading 36 sacrifice hits during the ’11 campaign. Despite the success, Gilbert was fired after the 1912 season. He had suffered several on-field injuries, which limited his usefulness as a player. The team wanted a more active manager. It did not help Gilbert’s cause that he was both highly paid relative to his peers, and he had a “dynamite” temper that rankled opponents and writers.33

The 1920 U.S. Census shows Billy, Blanche, and Althea living in Manhattan. Gilbert’s listed employment was a clerk with a steamship company.34 It listed his age as 44.35 But baseball, not clerking, was in Gilbert’s blood. In 1921, Gilbert found himself back in minor league baseball, managing the Waterbury Brasscos in the Class A Eastern League for the first of two seasons after he “spent the last few years managing several independent clubs in New York.”36 Waterbury went 64-85 in ’21 and remarkably improved to 84-66 in 1922, finishing second. One of his promising pitchers in 1922 was a 19-year-old Pat Malone, who despite frequently clashing with Gilbert, would eventually win 134 major league games and a World Series ring with the 1936 Yankees. 37 Gilbert managed the Denver Bears of the Class A Western League in 1923, but Denver went a dreadful 59-107. Available statistics are limited, but it seems that the club was plagued by woeful pitching.38

Gilbert returned to the Eastern League in 1924, skippering the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Hillies to a 70-81 record and a fifth-place finish. The Hillies were not without prospects. Young Mule Haas hit .299 for Pittsfield. He made his big league debut the next year and later won two World Series titles as Connie Mack’s center fielder on the Philadelphia Athletics. Pittsfield’s doubles leader — and best hitter — was Earl Webb. Webb banged out 42 two-baggers in his season under Gilbert. Like Haas, Webb also made his big league debut the next season and in 1931 crushed 67 doubles for the Boston Red Sox. That major league single-season record still stands.

On Sunday, August 7, 1927, Gilbert attended a Newark Bears doubleheader. By all accounts, his health was excellent. The next morning, at his Riverside Drive home, Gilbert died from a stroke.39 He was laid to rest at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York.40 His death certificate printed his occupation as “Secretary,” but at least two obituaries listed him as a scout for Newark. 41 Billy Gilbert was a true baseball man to the very end.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information provided in this bio are set forth in the endnotes below. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Trenton True American, August 25, 1908.

2 Annie Gilbert, FindAGrave.com, accessed June 29, 2020, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/27033238/annie-may-gilbert.

3 Annie Gilbert, FindAGrave.com.

4 1880 US Census, FamilySearch.org. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MWXH-HM9.

5 The Gilbert family lived close to present day Neshaminy High School, the alma mater of Len Barker, who pitched modern major league baseball’s eighth perfect game on May 15, 1981.

6 Interview with Larry Langhans, Archivist of Historic Langhorne Association, in March 2020.

7 1900 US Census, FamilySearch.org. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DZ1R-93?i=16&cc=1325221&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AM9FL-8HV.

8 Trenton Historical Society. http://www.trentonhistory.org/His/Recreation.html.

9 https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/t-fi11494/y-1897.

10 Stephen V. Rice, “Sammy Strang,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/09c30bed.

11 https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/leaders/l-NYSL/y-1899.

12 Pittsburgh Press, September 2, 1904.

13 Pittsburgh Press, September 2, 1904.

14 Dennis Pajot, “Tigers stage 9th-inning comeback in AL opener,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-25-1901-tigers-stage-9th-inning-comeback-al-opener

15 Pittsburgh Press, September 2, 1904.

16 The Machinations of Brush, Freedman and McGraw in 1902,” note to writer by Bill Lamb, 2020.

17 Lamb

18 Kevin Reichard, “Yankees roots don’t extend to Baltimore: historian,” Ballpark Digest, August 15, 2014, https://ballparkdigest.com/201408157555/major-league-baseball/features/yankees-roots-dont-extend-to-baltimore-experts.

19 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1904_World_Series.

20 It would be 90 years before a fall without a World Series. The World Series was played continuously from 1905 until the 1994 players strike.

21 Marriage record of William Gilbert and Blanche Morrison, FamilySearch.org. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:249Z-H3N

22 New London Day, January 19, 1907.

23 New York Times, January 13, 1907. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1907/01/13/104979766.pdf

24 New London Day, January 19, 1907.

25 New London Day, January 19, 1907.

26 New London Day, January 19, 1907.

27 New London Day, January 19, 1907.

28 https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/t-tt15030/y-1907.

29 Toledo News-Bee, September 14, 1908.

30 Althea Morrison Gilbert’s birth certificate, FamilySearch.org. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2W8L-1XP.

31 Trenton True American, August 10, 1909.

32 Mansfield (Ohio) Shield, April 25, 1911.

33 Youngstown (Ohio) Vindicator, November 25, 1912.

34 1920 U.S. Census, FamilySearch.org. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRJN-NW4?i=31&cc=1488411&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AMJ1N-41P.

35 Since the census was compiled in January 1920, that is further evidence that he was born in June 1875.

36 Warsaw (Indiana) Times, February 11, 1912.

37 Gregory H. Wolf, “Pat Malone,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/89ac07ec.

38 https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/t-db11229/y-1923.

39 Meriden (Connecticut) Record, August 9, 1927.

40 William Gilbert’s tombstone, FindAGrave.com, accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/13033846/william-oliver-gilbert

41 William Gilbert’s death certificate, FamilySearch.org. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2W52-ZZL?from=lynx1UIV8&treeref=MR6M-3KG

Full Name

William Oliver Gilbert

Born

June 21, 1875 at Tullytown, PA (USA)

Died

August 8, 1927 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.