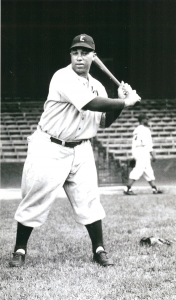

Bob Harvey

Bob Harvey was a menacing hitter, who reliably anchored right field for the Newark, Houston, and New Orleans Eagles from 1943 to 1951. Harvey was a large man, who stood 6-feet tall and weighed 220 pounds but was a capable fielder and possessed a deadly throwing arm.1 He threw right-handed but was a left-handed hitter, and consistently batted over .300 during his professional career.

Bob Harvey was a menacing hitter, who reliably anchored right field for the Newark, Houston, and New Orleans Eagles from 1943 to 1951. Harvey was a large man, who stood 6-feet tall and weighed 220 pounds but was a capable fielder and possessed a deadly throwing arm.1 He threw right-handed but was a left-handed hitter, and consistently batted over .300 during his professional career.

Robert Alexander Harvey was born on May 28, 1918, in Saint Michael’s, Maryland, a town of less than 1,500 residents along the Miles River on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. There is some uncertainty about his lineage. A 1930 Census record from St. Michael’s says his mother may have been a widow named Dacurcy Harvey and that he had three siblings, George, Lillian, and Lafayette.2 However, his death record from Archives.com suggests that his parents may have actually been John Hall and Lillian Harvey.

Harvey attended the Julius Rosenwald School3 in St. Michael’s, where he quickly developed beyond his peers as an athlete.4 As a teenager, he joined the St. Michael’s Red Sox, a local men’s baseball team, and was one of the club’s best players.5 After graduating from high school, Harvey enrolled at a teacher’s college across Chesapeake Bay, the Maryland Normal and Industrial School at Bowie, in 1936;6 he attended the school until 1938, when he left because of finances.7

At Bowie, Harvey played on the baseball, football, and basketball teams. Photographs show him wearing catching gear for the Bulls baseball team.8 He also starred in basketball; in the winter of 1937, Harvey scored 18 points as Bowie defeated Storer, 41-6.9

But it was in football that Harvey’s skills shone the greatest. On Thanksgiving Day 1936, in a game against rival Princess Anne, Harvey intercepted a pass on defense early in the game. On offense, he was a bruising running back. On one running play, “[l]ike a powerful machine Harvey went across for first touchdown of the game”; then he “smashed the line like a steam roller and went over for the second touchdown.”10 In the second half, Harvey caught a long reception and carried the ball to the goal line to set up the final score as the Bulls won 18-0, but failed to convert a single extra point.11 Harvey’s duties expanded the next year as he also became the Bulls’ place-kicker and performed well.12 In 1939, the school named Harvey to its Hall of Fame for football.13

After leaving college, Harvey moved back to the Eastern Shore and took up residence in Cambridge, Maryland, less than 30 miles from his hometown of St. Michael’s.14 He “took a job in the shipping department of Phillips Packing Co., a canned goods processor,” and played catcher for the company’s baseball team.15 By 1943, Harvey’s performance on the diamond attracted the attention of Webster McDonald, a manager and part-time scout for Abe and Effa Manley, the owners of the Newark Eagles.16

After receiving McDonald’s report, the Eagles invited Harvey to audition. He slammed two home runs in the 1943 tryout and the Manleys eagerly signed the 25-year-old slugger to a contract for $135 a month.17 The team was already deep at catcher, so Harvey moved to right field.18 He joined a talented squad, which included five future Hall of Famers including second basemen Larry Doby, center fielder Monte Irvin, catcher Biz Mackey, and player-manager Mule Suttles. The club played its home games at Ruppert Stadium when the Newark Bears of the International League were on the road. For Harvey, Ruppert’s right-field fence, which was just 305 feet down the line, must have been an enticing sight, although he could hit to all fields.19

The Negro leagues presented a chance for young black men to make a living playing baseball, although Harvey recalled life on the road was often hard:

“The traveling was really rough, says Harvey, who recalls having to board the team bus immediately after games and travel all night – often hundreds of miles –to get to the next game on time. “All our traveling was done by bus.”20

“Sometimes we played tripleheaders, where we’d play a pair (of games) at Yankee Stadium, keep our uniforms on and then drive to Trenton (New Jersey) for a night game.”21

The Eagles finished fourth in the NNL in 1943 behind the eventual Negro League World Series champions, the Homestead Grays. Harvey batted .323 with one homer and 10 RBIs in 17 games,22 as sportswriters were already recognizing him as a key run producer.23 In 1944, while Doby and Irvin served in the military, Newark added another future Hall of Famer, Ray Dandridge, but fell further in the standings to fifth place. Harvey again performed well, hitting .307 with 25 RBIs and a team-leading five home runs.24

After Suttles’ departure, future Hall of Famer Willie Wells became player-manager for 1945, although his tenure did not last long. After a dispute with owner Abe Manley over his use of pitcher Terris McDuffie, Wells resigned; Manley later traded him to the New York Black Yankees.25 Biz Mackey replaced Wells and was player-manager until the end of 1947. Under Mackey, Newark improved to finish third in the NNL, despite Doby’s absence. The 1945 campaign also proved to be memorable for Harvey. He married Catherine “Kay” Lewis, who would be his wife for 47 years until he died in 1992; the couple had a daughter named Cynthia.26 Now 27, Harvey had arguably his finest performance as a Negro Leaguer in 1945. According to the Howe News Bureau’s official statistics for the NNL, he led the Eagles with a .389 average, which was his career high, and finished behind only Josh Gibson (.393) among everyday players in the league.27 He struck 3 home runs and 12 doubles, and drove in 29 runs.28

In late September, New York’s Polo Grounds hosted a doubleheader showcasing four Negro League clubs closing out their schedules. In the first game, the Eagles played the Baltimore Elite Giants and won, 5-2, behind the strong pitching of teenage phenom Don Newcombe.29 The Birmingham Black Barons faced the New York Cubans in the second game. The game was unremarkable, except for the name Harvey in the box score as the center fielder for the Black Barons.30 “Bill Harvey [had already] pitched for the Elite Giants” and it appears the Eagles loaned Bob Harvey – who occasionally played center field31 – to Birmingham, as the Black Barons did not have another player on the roster with that surname.32 Harvey went 0-for-3 and recorded one putout in the loss.33

Later that fall, Harvey played for the Negro National League All-Stars with Mackey, Irvin, Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and Sam Bankhead, among others, in a five-game exhibition series against an all-white National League all-star team managed by Chuck Dressen.34 The results were expected to be presented to the New York State Committee Against Discrimination as part of a coming debate about whether to compel the major leagues to integrate.35 Dressen’s All-Stars opened with a sweep of a twin bill in tight contests at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, 5-4 and 2-1.36 After scoring a 10-0 victory in Ruppert Stadium behind the pitching of Ralph Branca, who matched his major-league teammates’ run production with 10 strikeouts, the series returned to Flatbush for a doubleheader. The major leaguers won the fourth game, 4-1, as Virgil Trucks cruised.37 In the final game, Johnny Wright – pitching under the alias Leroy Leafwich (because he was still in the Navy) – held the major leaguers scoreless for those five innings, but the game ended in a scoreless tie.38 Despite losing the series, Bob Harvey believed Negro League players could compete with their white counterparts, maintaining, “I don’t think they were any better than us.”39

At the start of 1946, the Eagles had high hopes as Doby returned, and Mackey believed they were ready to compete for a pennant.40 On Opening Day, Leon Day threw a no-hitter against the Philadelphia Stars.41 Newark streaked to wins in its next two games, and a double by Harvey punctuated an 8-2 win against the New York Black Yankees.42 The defending NNL champions, the Homestead Grays, were next; the Grays featured stars Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell.43 After falling behind 3-0, Mackey’s men battled back to tie the score, thanks in part to a sacrifice bunt by the versatile Harvey, before the umpire declared the game a tie at dusk.44

Despite the fast start, the Eagles lost four games in a row and sank to fourth place by the end of May.45 Monte Irvin and Bob Harvey suffered hitting slumps and were blamed for the sudden downturn.46 Mackey was reportedly frustrated with Harvey’s performance:

Another player who has also been in a slump is Bob Harvey, who was the second-best hitter in the league last year. Bob has been woefully weak at the plate and may be benched in an effort to get more batting punch in the lineup and give Harvey a chance to regain his batting eye, Bob is also overweight and may be forced to undergo a serious siege of reducing by Manager Mackey.47

However, the slide ended as quickly as it began; by June 9 the Eagles nested into first place.48 They played well and claimed the first-half league title by the end of June after sweeping a doubleheader from Philadelphia; Harvey’s three-run triple against the Stars proved to be the championship-clinching hit.49

In the second half, the Eagles avoided any inconsistency, flew to a 17-4 start, which included a 14-game winning streak, and easily won the league championship again.50 Newark finished with a combined record of 56-24-3.51 For his part, Harvey saw his batting average plummet to .284.52

Harvey played an immediate role in deciding the Negro League World Series against the formidable Kansas City Monarchs, champions of the Negro American League. He is remembered more for his glove and baserunning than his bat in the series, however. At the Polo Grounds, in Game One of the Series, Satchel Paige relieved Hilton Smith for the Monarchs and shut down the Eagles’ bats for four innings, as Kansas City won 2-1. Kansas City had taken an early 1-0 lead after Harvey allowed a ball to roll between his legs to the right-field wall in the first inning.53 After Harvey led off the fifth inning with a single, Leon Ruffin grounded out. Harvey slid hard into second and “blocked [shortstop Jim] Hamilton on the double play throw and the contact with the heavy Newark outfielder broke Hamilton’s leg in two places.”54

The Series was a back-and-forth affair that went a full seven games with the Eagles claiming their first and only Negro League World Series championship after a 3-2 victory at Ruppert Stadium in the finale. Based on the box scores, which are available for five of the contests, Harvey collected six hits in the Series, but was not mentioned in the summaries after Game One. Harvey fondly remembered the 1946 championship as “one of the best times of my life.”55

The following summer one of Harvey’s most memorable moments occurred in a doubleheader in Yankee Stadium against the Black Yankees, although his own memory of the game was probably fuzzy:

A freak play in the first game put the officials at a test for a rare ruling that drew a “protested game” beef from the Yankee manager, Marvin Barker. Dick Seay, Yank third sacker, walked to lead off the fourth inning. Bud Barbee poled a long fly over the right field barrier. Bob Harvey galloped over fast, snared the ball and crashed waist high into the stands. Seay tagged up and went all the way home.

Dusty Rhodes, plate umpire, ruled the hitter out and the runner safe, but Barker maintained Harvey took the ball out of the playing field and Barbee was entitled to a home run.56

Harvey did not attempt a throw home on the play after being knocked unconscious when he smashed into the stands, but he held onto the ball, and Newark won the game, 9-8.57 By July 4 Harvey had shaken off any aftereffects from the play as he and Doby homered in a win over the Philadelphia Stars in Doby’s final NNL game before he joined the Cleveland Indians.58

With the loss of Doby’s offensive production, the Eagles’ championship reign quietly ended.59 They finished 1947 with a respectable record of 50-38-1, including the best record in the first half, but in the second half the Birds fell behind their rivals, the New York Cubans, who were declared the NNL champions without a playoff series.60 There was bad blood with the Cubans as the players brawled in early May during a 10-2 Newark win.61 Harvey rebounded, batting .335 (seventh among qualifiers) with 17 doubles and 3 home runs.62 He spent the winter playing baseball in Puerto Rico for a monthly salary of $1,500, which was his highest ever.63

Change was in the air in 1948. It would be the last season the Eagles played in Newark, the end of the NNL, and the final Negro League World Series, although it is unlikely anyone realized what was happening as the campaign got underway. The transition began in the winter, as the Manleys released Mackey, who they believed lacked discipline, and installed William Bell as the manager.64 The move did not help their fortunes, however, as the Eagles tumbled to a disappointing third-place finish.65

Despite the decline in the standings, columnist Dan Burley noted “dependable Bob Harvey, who while rather portly, can still wallop the ball and manage to get under flies.”66 Now 30, Harvey led the Eagles with a .363 batting average, fourth among the league’s hitters;67 and for the first time in his career, he was chosen for the East-West All-Star Game.68 In the game, played at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Harvey had one plate appearance for the East, but failed to reach safely, as the West won, 3-0.69

The Eagles played their final game at Ruppert Stadium on September 8, 1948, and their last league games as the Newark franchise four days later in Yankee Stadium.70 The Manleys lost their interest in continuing and sold the club to “Dr. W.H. Young, a Memphis dentist, and Hugh Cherry of Blytheville, Arkansas, for a reported $15,000. That was a fraction of the $100,000 often reported as the sum Abe had invested in the team.”71 By late fall, the NNL dissolved as a result of declining attendance; the Eagles joined the Negro American League and relocated to Houston, Texas.72 During the winter, the new owners sold Monte Irvin to the New York Giants.73

Harvey brought his steady bat to Houston as he hit .299 in 1949.74 Goose Curry invited him to be an instructor for Curry’s Delta Negro Baseball School the following February.75 In two seasons in Houston, the Eagles, who played their home games at Buffalo Stadium, suffered back-to-back fourth-place finishes.76 The 1949 squad finished just under .500. The next year was a disaster as Houston crashed to 23-41-1.77 Harvey performed well, hitting a team-leading .367 in 1950, sixth in the NAL batting race.78 He was an All-Star again, this time as a member of the West squad.79 Harvey batted twice in the contest, drawing a walk and scoring a run on an error “when Ben Littles of Philadelphia lost [a] lazy fly ball in the sun.”80 Later in the game, Harvey returned the favor as he also lost a ball in the sun, which led to a run for the East. The West won, 5-3.81 Harvey barnstormed against a group of black major leaguers in the offseason.

The 1951 season was Harvey’s last in the Negro leagues. Before the season, the Eagles moved to New Orleans.82 The change of venue did not improve the results, however, as they started 9-17.83 The 33-year-old Harvey hit at a furious pace, however, and posted a .474 batting average into June.84 He abruptly left the club to join the Elmwood Giants in the semipro Manitoba-Dakota Baseball League.85 Harvey led the Man-Dak League with nine home runs and batted .306 with 43 RBIs.86

Back in New Orleans, the Eagles were in last place of the NAL’s Western Division with a 13-22 record on July 4,87 and management soon began to cut its losses. Jehosie Heard and Curley Williams were sold to the St. Louis Browns in late August.88 In January the end finally came as the Eagles withdrew entirely from the league.89 Owners Martin and Young offered to sell the contracts of the remaining players to other NAL franchises and announced Harvey’s availability.90

In February 1952, the Birmingham Black Barons purchased Harvey’s contract.91 Throughout the early spring, the Birmingham World published reports of the Black Barons’ expectation of Harvey reporting for spring training.92 However, his name never appeared in a box score or game story for the Black Barons in 1952. In Canada the newspapers also anticipated Harvey’s return to the Man-Dak League for the Winnipeg Giants.93 However, it appears he never actually reported. Barry Swanton and Jay Dell-Mah concluded that “(h)e retired after the ’51 campaign”94 and Harvey told Ross Forman, “I played in Canada for a year.” 95

Based on the incomplete statistics available from the Howe News Bureau, Harvey had a lifetime batting average of .338 during his career in the Negro Leagues. Seamheads.com assesses him as having an OPS+ of 119, although the calculation is based solely on his performance in the NNL.96 Although he did not face Harvey often, pitcher Bill Greason remembered him as a dangerous left-handed slugger.97

After his baseball career, Harvey and his wife, Kay, settled in Montclair, New Jersey, where the couple liked to entertain in their home.98 He spent 32 years working in the shipping department for Hoffmann-LaRoche, a pharmaceutical company, before retiring in 1983.99 Despite his retirement, he worked part-time as a crossing guard at an elementary school.100 Late in his life, Harvey’s baseball accomplishments were remembered by the public as he regularly appeared at autograph signings, reunions, and Negro League appreciation days at major-league ballparks, including Memorial Stadium, Veterans Stadium, and Shea Stadium.101 On one occasion, Harvey remarked, “Society must have had a guilt trip because it’s taken close to 40 years for them to recognize the former players of the Negro League.”102 However, he denied any bitterness over not playing Organized Baseball, adding, “Baseball gave me the opportunity to see the world and I wouldn’t have traded it for anything.”103

Harvey died from a blood disorder on June 27, 1992, at the age of 74.104 He is buried at the Rosedale Cemetery in Montclair, New Jersey.

Acknowledgements

Like a pitcher with a collection of all-star defenders behind him, the author is grateful for all the help he received on this project. Everett “Ev” Cope of Bozeman, Montana, provided a copy of Ross Forman’s Sports Collectors Digest article on Bob Harvey. Thomas Zocco and Larry Lester provided Jonathan Welsh’s excellent 1991 feature on Harvey from the Montclair Times. John Zinn even offered to drive to the Montclair Public Library to search for the same article. Paul Brennan, a staff member of the library, provided the author with a copy of Harvey’s obituary. Gary Ashwill of Seamheads.com helped explain Harvey’s 1945 appearance for the Birmingham Black Barons. Jay-Dell Mah and Rick Bush provided research on Harvey’s time in Canada. Charles Ruberson, a volunteer in the Maryland Room of the Talbot County Library, provided useful information about Harvey’s education in St. Michael’s. Finally, Katherine Hayes and Arlene Creek of Bowie State University provided invaluable help with Harvey’s college years, including photographs, which have not been seen for decades.

Notes

1 “Two Big League Negro Baseball Teams Here Soon,” Daily Standard (Sikeston, Missouri), June 25, 1951.

2 Maryland. Talbot County. 1920 U.S. Census.

3 Julius Rosenwald Schools were established by Rosenwald, an early owner of Sears Roebuck & Co., to serve African-American children in the South.

4 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 368.

5 Dr. Carole Marks, Lift Every Voice: Echoes from the Black Community (Wyes Mill, Maryland: Chesapeake College Press, 1999, Kindle Edition), 84-85.

6 In 1938 the school changed its name to the Maryland Teachers College at Bowie and later became Bowie State University. “The Eye Salutes President James,” The College Eye, Vol. 6, No. 1, September-October, 1938: 1 accessed at bowiestate.edu/academics-research/library/departments/archives-and-special-collectio/the-college-eye-1935-1967/.

7 Katherine A. Hayes, archivist, Department of Archives & Special Collections, Thurgood Marshall Library, Bowie State University, email correspondence with author, October 10, 2018; Jonathan D. Welsh, “Bob Harvey Recalls: Race Line Clouded His Season in Sun,” Montclair (New Jersey) Times, May 23, 1991: A1. There is some speculation that Harvey may have attended Bowie in 1939, but in a preview of the coming basketball season The College Eye reported the loss of Harvey. Thelma Hawkins, “Outlook for Basketball,” The College Eye, Vol. 6, No. 2, November-December, 1938: 12. Additionally, Harvey’s name was absent on the roster of the baseball team in 1939. Robert “Pope” Mack, “Sports Review,” The College Eye, Vol. 6, No. 4, June 1938: 10.

8 Today Bowie State’s athletic teams are nicknamed the Bulldogs, but the contemporaneous student newspaper during Bob Harvey’s playing days – The Normal Eye, later renamed The College Eye – referred to all athletic teams as the Bulls.

9 “Storer Topples to Bowie,” The Normal Eye, Vol. 4, No. 4, March 1937: 7.

10 Francis Nool, “Bulls Top Princess Anne,” The Normal Eye, Vol. 4, No. 3, December 1936: 4, 6.

11 Ibid.

12 Charles Frisby, “Cheyney Traps Bowie Bulls 48-0,” The Normal Eye, Vol. 5, No. 2, December 1937: 8.

13 Arlene Creeke, associate athletic director for internal affairs/senior woman administrator, email correspondence with author, November 1, 2018; Ross Forman, “Bob Harvey Recalls Negro League Days,” Sports Collectors Digest, June 21, 1991: 108; Riley. Harvey is not listed as a member of the Bowie State Athletic Hall of Fame on the school’s website. Nevertheless, the university has a plaque identifying him as a member of the Hall of Fame for football in 1939.

14 Welsh.

15 Ibid; James Overmyer, Queen of the Negro Leagues: Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1998), 195.

16 Overmyer, 195.

17 Riley, 368; Welsh; Forman, 108.

18 Overmyer, 195.

19 Alfred M. Martin, The Negro Leagues in New Jersey (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 63.

20 Welsh.

21 Forman, 108.

22 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=harve01bob.

23 “Eagles and Philly Clash in Twin Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 14, 1943: 18.

24 Official Negro National League Statistics for 1944, compiled by Howe News Bureau (Chicago). Seamheads.com reckons Harvey’s batting average as an incredible .426 over 27 games for the 1944 season, but Howe’s statistics included 41 games played.

25 Oyermyer, 81-82; Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Washington: Potomac Books, 2011), 110.

26 “Obituaries,” Robert A. Harvey, Montclair Times, July 2, 1992 B4.

27 Ibid.; Official Negro National League Statistics for 1945, compiled by Howe News Bureau.

28 Official Negro National League Statistics for 1945, compiled by Howe News Bureau.

29 “Eagles Defeat Elites, Cubans Upset Barons,” New York Amsterdam Times, October 6, 1945: 22.

30 Ibid; Gary Ashwill, Seamheads.com, email correspondence with author, October 16, 2018.

31 Martin, 63; “Eagles Top Giants In Doubleheader,” Norfolk (Virginia) Journal and Guide, August 9, 1947: 20 (“The second double by Bob Harvey, Eagles’ centerfielder, drove in the winning run in a seven-run rally”).

32 Ashwill email.

33 “Eagles Defeat Elites.”

34 Dan Burley, “Big Leaguers Play Negroes,” New York Amsterdam Times, October 6, 1945: 1, 3.

35 Ibid.

36 “Dressens Cop Two From Negro Stars,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1945: 13.

37 “Dressenmen Annex Four in Rover Over Negro Stars,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1945: 17, 18.

38 Dressenmen: 17.

39 “Former Players Visit Black Baseball Exhibit,” Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey), September 28, 1984: A-12.

40 “Eagles Satisfy,” Newark News, April 9, 1946.

41 “Fireworks at Eagles Game,” Newark News, May 6, 1946.

42 “Test Ahead for Eagles,” Newark News, May 13, 1946.

43 “Eagles Hold Top in 3-3 Tie Game,” Newark News, May 13, 1946.

44 Ibid.

45 “Negro National League Standings (as of May 26),” New Jersey Afro-American, June 1, 1946.

46 “Biz Mackey Irked Over Slump; Cracks Whip Over Newark Eagles,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 1, 1946: 11.

47 Ibid.

48 “Eagles Move to the Top,” Newark News, June 10, 1946.

49 “Eagles Clinch Midway Title,” Newark News, July 1, 1946.

50 Diamond Dust (Standings),” New Jersey Afro-American, September 7, 1946; “Eagles Streak Reaches 14,” Newark News, September 3, 1946.

51 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1946&teamID=NE.

52 Official Negro National League Statistics for 1946, compiled by Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

53 Sam Lacy, “19,423 Fans See Paige in Brilliant Performance,” New Jersey Afro-American, September 21, 1946.

54 Lem Graves Jr., “Paige Leads K.C. to Series Victory 2-1,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, September 21, 1946: A1.

55 Forman, 108.

56 “Yanks and Eagles Split Doubleheader, 9-8, 5-6,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, July 4, 1947: 5.

57 Haskell Cole, “Doby Stars for Newark,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 5, 1947: 15.

58 “Doby Hits Homer in Final Game with Newark Eagles” Atlanta Daily World, July 9, 1947: 5.

59 Overmyer, 239.

60 Luke, 139; seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1947&lgID=NN2.

61 “Johnson Fines Cuban-Newark Brawlers,” New York Amsterdam News, May 3, 1947: 13; “Photo Standalone 40,” Chicago Defender, May 10, 1947.

62 Official Negro National League Statistics for 1947, compiled by Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

63 Forman, 108.

64 Luke, 141.

65 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1948&lgID=NN2.

66 Dan Burley, “Confidentially Yours,” New York Amsterdam News, May 29, 1948: 20.

67 Official Negro National League Statistics for 1948, compiled by Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

68 “Newark Eagles Play Chicago Giants Sunday, New York Amsterdam News, August 7, 1948.

69 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 313.

70 “Eagles, Cubans Play Last Doubleheader in Stadium,” New York Amsterdam News, September 11, 1948: 15.

71 Luke, 145.

72 A.S. “Doc” Young, “Negro Leagues Reorganize in 10-Club Group,” The Sporting News, December 8, 1948: 31.

73 “Giants Mum on Reports They Signed Monte Irvin,” The Sporting News, January 26, 1949: 6; “Giants Get Three Negroes for Trials at Jersey City,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1949: 7.

74 Official Negro American League Statistics for 1949, compiled by Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

75 “Baseball School to Open Feb. 27: Goose Curry Heads Set-Up in Greenville,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 11, 1950: 22.

76 cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20American%20League%20(1937-1962)%202018-04.pdf.

77 Ibid.

78 Official Negro American League Statistics for 1950, compiled by Howe News Bureau (Chicago).

79 “West All-Star Team Roster Completed,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, August 12, 1950: D20.

80 Lester, 347.

81 Lester, 348-49.

82 Russ J. Cowans, “Clowns Start with a Rush to Lead NAL,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1951: 16.

83 Russ J. Cowans, “Monarch Lefty Setting Record Strikeout Pace,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1951: 10.

84 Ibid.

85 “Turk Sends ’Em, Haas Grabs ’Em,” Winnipeg Free Press, June 8, 1951.

86 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006), 80-81.

87 Russ J. Cowans, “K.C. Monarchs and Clowns Win First-Half Titles,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1951: 33.

88 Emmett Maum, “Brownies Obtain Four Performers in Negro Leagues,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1951: 22.

89 Russ J. Cowans, “Negro League Cut From Eight Clubs; Will Go With Six,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1952: 19; Russ J. Cowans, “Negro League Claims Players of New Orleans,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1952: 17.

90 Cowans, “Negro League Claims Players.”

91 “Birmingham Black Barons Have Tradition of Great Performers” Atlanta Daily World, February 20, 1952: 5.

92 “New Players Expected to Join B’ham Black Barons” Birmingham World, April 1, 1952: 3; “Birmingham Black Barons Kickoff Training Drills,” Birmingham World, April 8, 1952: 5; “Black Barons to Meet Chi American Giants Sunday,” Birmingham World, April 11, 1952: 6.

93 “Winnipeg Giants Release Names of Probable Lineup,” Brandon (Manitoba) Daily Sun, April 22, 1952; “Minot Thumps Giants,” Winnipeg Free Press, May 27, 1952; attheplate.com/wcbl/negro_3.html.

94 Swanton and Mah, 81.

95 Forman, 108.

96 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=harve01bob.

97 Interview with author at the Southern Negro Baseball Conference, October 4, 2018.

98 “Mrs. Kay Harvey Entertains in Montclair Home,” New York Amsterdam News, February 7, 1959: 12.

99 Forman, 108; Welsh, A-10; Martin, 63; Riley, 368.

100 Forman, 108.

101 “Former Players Visit Black Baseball Exhibit,” Courier-News, September 28, 1984: 12; Carl Babati, “The Other Game,” Courier-News, August 16, 1988: 19; Peter Genovese, “Black Players Were a Hit When the Big Leagues Were Foul,” Central New Jersey Home News (New Brunswick), February 5, 1989: 15; “Former Negro Major League Baseball Stars Feted by the Baltimore Orioles,” Atlanta Daily World, June 12, 1990: 5; “Upper Deck Heroes to Honor Negro Leaguers,” Atlanta Daily World, August 4, 1991: 8; Howie Evans, “Mets Honor Stars from Negro Leagues,” New York Amsterdam News, May 30, 1992: 48; Kenneth Meeks, “Ex-Negro League Baseball Players Sign Autographs,” New York Amsterdam News, June 6, 1992: 51.

102 Meeks.

103 Forman, 108.

104 “Obituaries,” Robert A. Harvey, Montclair Times, July 2, 1992 B4Martin, 63.

Full Name

Robert Alexander Harvey

Born

May 28, 1918 at St. Michael's, MD (US)

Died

June 27, 1992 at Montclair, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.