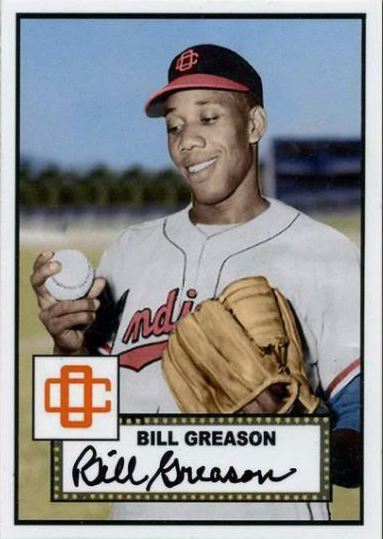

Bill Greason

Greason’s major-league career consisted of only three appearances, but his contributions to baseball history should not be underestimated. Before his time with the Oklahoma City Indians, he had earned the Birmingham Black Barons’ sole victory in their loss to the Homestead Grays in the 1948 Negro World Series. After his brief stint with the Cardinals, Greason played winter ball for Puerto Rico’s Santurce Cangrejeros (Crabbers) in 1954-55. He teamed with two future Hall of Famers – Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente – to win the Caribbean Series championship. Another teammate, Don Zimmer, called it “probably the greatest winter league baseball club ever assembled.”1

Greason’s baseball career also intertwined with other experiences to create a compelling portrait of what life was like for an African-American man during segregation, as well as in its aftermath, in 20th-century America.

William Henry Greason was born on September 3, 1924 in Atlanta, Georgia, the middle child of James and Lizi Greason’s five offspring; he had two older brothers, James Jr. and Willie, and two younger sisters, Jamie Mae and Louise. James Greason was a laborer and Lizi took in laundry for white families, which meant, in Bill Greason’s words, that they “were poor folk.”2

Greason grew up across the street from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on Auburn Avenue – now known as the Sweet Auburn Historic District – a black neighborhood in segregated Atlanta. Both men graduated from Booker T. Washington High School, but they were not classmates as Greason was five years older than King; prior to attending Washington HS, Greason had also attended David T. Howard High School.

As a youth, Greason and his friends played pickup baseball games on sandlots, where his natural talent came to the fore. He confessed later in life, “I never dreamed that I would have been a baseball player. Nobody taught me how to play … It was a gift.”3

Though Greason had no baseball coach, he did have parents who taught him how to cope with life in the racially segregated South. They instructed him to respect all people – no matter their race – and told him not to worry about what other people might call him or think of him because of his color. Greason’s mother said to him, “You are somebody. You are God’s child. We are to treat each other with respect and to love each other.”4 Her edifying comments also instilled a belief in God that Greason called on during the horrors of battle in World War II and that helped lead to his eventual post-baseball vocation as a minister.

In 1943, Greason entered the United States Marine Corps and became one of the Montford Point Marines, black soldiers who underwent basic training at a segregated facility (Montford Point) in Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Another member of that unit was Dan Bankhead, who became the first African-American pitcher in the majors with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Greason served in the Pacific Theater and landed at Iwo Jima as part of the 66th Supply Platoon on the fourth day of the American invasion in 1945. He remembered, “Two of my best friends were killed on that island. I prayed and said, ‘Lord, if you get me off this island, whatever you want me to do, I’ll do it.’”5 Greason survived and completed his tour in the USMC with 13 months as a member of the American occupation force in Japan, where he was stationed at Sasebo and Nagasaki after the United States had dropped an atomic bomb on the latter city.6

After being discharged from the Marines and returning stateside, Greason played quarterback in for two seasons (1946-47) for the Atlanta All-Stars, a semipro football team.7 He embarked upon his career in professional baseball thanks to encouragement from Sammie Haynes, the manager of the Atlanta Black Crackers, who had been aware of Greason’s pitching talent since his days of playing on Atlanta’s sandlots. He spent the 1947 season with the Nashville Black Vols, for whom he posted a 12-4 record.8 In 1948, he went to spring training with the Asheville Blues of the newly formed Negro American Association and caught his first big break. The Blues played a game against the Birmingham Black Barons, and Greason so impressed Birmingham’s catcher, Pepper Bassett, that he convinced legendary player/manager Lorenzo “Piper” Davis to acquire the young pitcher. According to Greason, “That [the game] was on a Monday night. Saturday morning I was in Birmingham. I don’t know how they got me, they bought me or whatever, but in 1948 I was with the Barons.”9

Birmingham had won Negro American League (NAL) pennants in 1943 and 1944 but had lost the Negro World Series to the powerful Homestead Grays both times. The 1948 team was the last great Black Barons squad, featuring four future major leaguers in Greason, 17-year-old Willie Mays, Jehosie Heard, and Artie Wilson. Jimmy Newberry and Bill Powell tied for the team lead with seven victories apiece, while Greason chipped in six wins during the league season. They won the NAL’s first-half championship and defeated the second-half champion Kansas City Monarchs in the playoffs, with Greason starting and winning the final game to clinch a 4-3 series victory. The triumph set up a rematch against the Black Barons’ old nemesis, the Negro National League (NNL) champion Grays, in what turned out to be the last Negro League World Series ever played.

Birmingham had won Negro American League (NAL) pennants in 1943 and 1944 but had lost the Negro World Series to the powerful Homestead Grays both times. The 1948 team was the last great Black Barons squad, featuring four future major leaguers in Greason, 17-year-old Willie Mays, Jehosie Heard, and Artie Wilson. Jimmy Newberry and Bill Powell tied for the team lead with seven victories apiece, while Greason chipped in six wins during the league season. They won the NAL’s first-half championship and defeated the second-half champion Kansas City Monarchs in the playoffs, with Greason starting and winning the final game to clinch a 4-3 series victory. The triumph set up a rematch against the Black Barons’ old nemesis, the Negro National League (NNL) champion Grays, in what turned out to be the last Negro League World Series ever played.

Homestead fielded future major leaguers of their own – including Luke Easter, Bob Thurman, and Luis Márquez – and they made short work of Birmingham, even without the advantage of a single home game.10 The Grays took Game One in Kansas City by a 3-2 margin, and then defeated the Black Barons 5-3 at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field to take a 2-0 series lead.

Greason earned the lone win for Birmingham at home in Game Three with both his arm and his bat. He entered the game in the eighth inning to relieve starter Alonzo Perry, who had allowed the Grays to tie the game at 3-3. In the bottom of the ninth, Greason hit a one-out single, advanced to second when John Britton walked, and scored the winning run as Willie Mays “hit through [pitcher Ted] Alexander’s legs to center field.”11 It was the only bright moment for the Black Barons; the Grays won the next two games – in New Orleans and then back in Birmingham – to wrap up the championship.

In 1949, Greason returned to the Black Barons and was selected to play in the annual East-West All-Star Game, in which he spun three shutout innings. The Birmingham team was in a downturn, however, and he posted only a 7-12 record that season.12 The reversal of fortunes stemmed largely from the rapid rate of player defections to Organized Baseball that occurred after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. The Negro Leagues were losing all of their best talent, which caused a decline in the quality of play and a resultant decline in attendance. After the NNL was merged into the NAL in 1949, it became obvious that the Negro Leagues would not last much longer.

Nevertheless, Greason returned to the Black Barons in 1950 and posted a 9-6 record with a 2.41 ERA before moving south of the border to the Jalisco Charros of the Mexican League late in the summer.13 In 14 games, he was 10-1, leading the league in winning percentage, while posting a 3.46 ERA. Jalisco made it to the Mexican League championship series but lost in six games to the Algodoneros de Unión Laguna. After his first foray into Latin American baseball, Greason then joined the Cuban winter league’s Marianao franchise in early 1951. In seven games, he was 2-2 with a 3.38 ERA.

Greason gained notice from Organized Baseball and was offered a tryout with the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks in spring training of 1951. He arrived to Oakland’s spring training camp late due to his playing in Cuba and, when he failed to make the team, the Oakland Tribune reported, “Sideliners believe that had Greason reported March 1, instead of two weeks late . . . he might still be with the Oaks.”14 Instead, the Oaks offered him a spot with their affiliate in Wenatchee, Washington, but Greason declined their offer and returned to Jalisco, where he said he could make more money.15 He was much less successful in Mexico this time around, though, going only 1-4 with a 7.94 ERA in seven games.

Greason left Jalisco early in the season and returned to Birmingham, where he quickly regained his form. Prior to a late-June exhibition game against the New Orleans Eagles, it was reported that “less than 48 hours after William Greason signed his 1951 contract with the Birmingham Black Barons he had pitched two winning games against the Kansas City Monarchs.” 16 Greason had pitched five innings in relief in a 4-3 victory on a Saturday night and had followed up that performance with a 5-0 shutout in the first game of a doubleheader the next day. Entering the July 28 game against New Orleans, Birmingham had a 16-3 record in NAL games.17

In light of the good season the Black Barons and Greason were having, he was chagrined when was recalled to active military duty with the Marines later that summer. Greason was fortunate not to have to deploy overseas for another tour of combat, this time in the Korean War. He remembered, “I had a good camp commander. He said, ‘That’s a no-win war. You stay here. I’m going to have a baseball team.’”18 During the time that Greason played ball for the Camp Lejeune ball club, he lost just once; in one game, he won a 1-0 decision over Brooklyn Dodgers ace Don Newcombe.19

Though the integration of both baseball and the armed forces was under way, Jim Crow still ruled in the South, and Greason once was prohibited from sitting with his teammates at a game in Florida. He remembered this incident as one of the few that angered him, saying, “I’m a Christian man, but I wasn’t Christian at that moment. Something had to be said. That was awful.”20

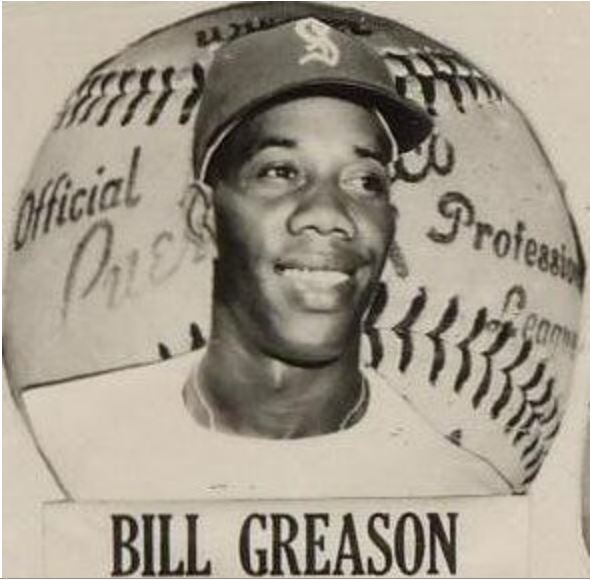

Greason received his second chance at a minor-league roster spot under most unusual circumstances. The story was that E. J. Humphries, owner of the Double-A Texas League’s Oklahoma City Indians, called Greason after hearing about him from a Marine sergeant who had become stationed in Oklahoma.21 He finally entered Organized Baseball when he signed a contract with Oklahoma City on July 28. Dave Hoskins, who had formerly pitched for the Homestead Grays from 1944 to 1946, had integrated the Texas League for the Dallas Eagles earlier that season, but Greason was the first black player in the state of Oklahoma, and the excitement was palpable for the city’s black community. Russell Perry, an African-American youth who later became one of the city’s civic leaders, remembered that, for him, “It was like Jackie Robinson was here . . . Everybody was very, very proud of him.”22

As for Greason’s reception throughout the Texas League, he declared that the hometown fans were kind and that Oklahoma City provided a good environment in general, though he did not socialize with any of the other Indians players – who were all white – outside of the ballpark. Things were different on the road though, and Greason recalled, “In other towns, they would give us a tough time. Me, at least. Same thing with Dave [Hoskins]. They’d call you names you never heard of.”23 He kept his composure – his anger in Florida had been an exception, not the rule – and eventually some of the fans began to relent. Greason has often retold the tale about a white woman in Beaumont who had made it her duty to torment him for two seasons, but who then approached him toward the end of 1953 and commended him for his grace under pressure.

On August 3, 1952, Hoskins and Greason matched up in what The Sporting News called “the novelty of the first all-Negro duel in Texas League history.”24 Though it may have been a “novelty” at the time, it was a harbinger of things to come as teams became aware of both the talent and the popularity of black ballplayers. As evidence of this, The Sporting News also made note of the fact that “more than 11,000 persons, over half of them Negroes, packed the park in Dallas to see the rare match.”25 Greason outdueled Hoskins that day to earn his second win in four days with the team as the Indians prevailed, 3-2. He not only started out of the gates quickly, but he ended up with a 9-1 record and a superb 2.14 ERA that made him a hot commodity.

After his breakout 1952, a bidding war for Greason began between several major-league teams, including the Yankees and the Red Sox, two teams that had yet to employ a black player. Humphries set a high price on his star pitcher’s services. When asked what it would take to get Greason, he replied, “I might listen to something like $75,000, with a few players thrown in – and then I’d have to have the choice of what men I get.”26 He turned down $50,000 offers from both the Yankees and Red Sox, and it was suspected that he wanted “to use Greason for his box office value for one more season, then up the price to $100,000 for him next winter.”27

Greason started slowly in 1953, endangering Humphries’ plan; though he finished with a flourish and emerged with a 16-13 record, his ERA had increased to 3.61. After the season, the St. Louis Cardinals acquired Greason and Texas League batting leader Joe Frazier from the Indians in exchange for four players and $25,000 cash, which was considerably less than Humphries’ original expectations.

Obtaining Greason was a change for the Cardinals under their new owner and president, August A. “Gussie” Busch, Jr., who had recently purchased the team from Fred Saigh, a staunch segregationist who had run afoul of baseball because of his conviction for tax evasion. St. Louis had been one of the cities that had made life most miserable for Jackie Robinson in 1947, but Busch was making changes and the Cardinals would soon be integrated. The Sporting News predicted as much when it reported that Greason was “likely to become the first Negro player ever to perform for the Cardinals.”28

That distinction, however, went to first baseman Tom Alston, who began the 1954 season on the Cardinals’ roster; Greason was called up in late May after starting 4-5 with the Triple-A Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds. His most impressive outing came at Kansas City on May 9, when he had a perfect game through six innings and a one-hitter through nine. He stayed in until the 15th, when he finally weakened and lost, 2-1.29 After that game, he won three straight decisions to earn his May 28 callup to St. Louis, which wanted him because the big club’s pitching had been erratic.30

Greason soon found out that integration did not yet mean equality to the Cardinals’ front office. When St. Louis forced him to take a pay cut from the $1,200 per month he had been making in Triple-A to $900 per month, his promotion turned out not to be the exhilarating moment he had anticipated. Greason protested the pay cut and was given a “take it or leave it” ultimatum that made him bitter and dejected. He said, “I tried to get there for years, and then when I got there, I didn’t want to stay.”31

Greason’s already low spirits were not buoyed by the way Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky handled him, which was to remove him from games “faster than [he] could spew tobacco juice from his front teeth.”32 His major-league debut came on May 31, 1954 in the first game of a doubleheader against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. It was a brief start in which he surrendered five runs (all earned) and three homers – two by Hank Sauer and one by Ernie Banks – in three innings of a 14-4 rain-shortened (seven-inning) loss.

Greason’s second start was on June 6 against the Phillies in St. Louis, and it went even worse. He surrendered a leadoff homer and walked the next two batters before being pulled by Stanky. Greason knew his days in St. Louis were numbered when Stanky’s only words to him were, “Get the damn ball over the plate.”33 His premonition was correct as he made one final appearance on June 20 and pitched a scoreless inning of relief against the New York Giants, though he did allow a single and a walk, before being sent back to the minors. After never really being given a chance in the majors, Greason was relieved to return to Columbus, where he finished the 1954 season with a 10-13 record. The major leagues never beckoned again, but Greason’s final tally of 0-1 with a 13.50 ERA for the Cardinals fails to define him as a ballplayer.

On the heels of his miserable experience with St. Louis and his subpar record for Columbus, Greason was happy to be in Puerto Rico and performed well for Santurce. He amassed a 7-2 record and won two games in the Caribbean Series, including the clincher. In his Game Two start against Panama, he also hit a home run to help his own cause. Later in life, Greason recalled, “It was great … one of the largest crowds I had ever pitched before. I remember the home run and winning, 2-1. There was a lot of excitement competing against Panama, Cuba, and Venezuela.”35 After the series-clinching victory over the Carta Vieja (Panama) Yankees on February 14, 1955, he was named to the series’ All-Star team along with four of his teammates, which included future baseball lifer and Series MVP Don Zimmer.

The winters in Santurce were special to Greason. Though the team did not win another championship during his seasons there, he continued to shine. During his seven seasons with the Crabbers, he posted a record of 46-31 with a 2.99 ERA, striking out 372 batters in 701 innings.36 The caliber of the Puerto Rican league was quite high then – it was generally regarded as just a shade below the majors.

The Cardinals still had Greason under contract, yet his performance in Puerto Rico had no impact upon his status with the franchise. In fact, in 1955, St. Louis dropped Greason to their Double-A affiliate. He found himself back in the Texas League, this time with the Houston Buffaloes, for whom he posted a 17-11 record, albeit with a 4.16 ERA. The Texas League had continued to move forward with integration; Greason was now teamed with first baseman Bob Boyd, who, in 1954, had become the first black player in the Houston franchise’s 66 years of existence. No matter their fortunes elsewhere, the two men were stars for the Buffs in 1955, as evidenced by games such as an 8-4 victory over the San Antonio Missions on June 24, in which Greason earned his fifth victory and Boyd hit a grand slam. Houston finished 86-75 and advanced to the Texas League championship series, which they lost to Shreveport.

Greason got a chance to play in another nation – the Dominican Republic – in January 1956. Santurce allowed him to join the Licey Tigres for a three-game playoff series to determine the other finalist for the Dominican league championship. In Game One on January 25, Greason and Ron Kline of Águilas Cibaeñas engaged in a tremendous duel. Greason pitched 13 innings and Kline 14, and neither allowed a run. Águilas finally won in the 15th, 1-0.37

Greason returned to the Buffs in 1956 and had a 10-6 record before he was promoted back to Triple-A ball. He joined the Cardinals’ affiliate in Rochester (New York), which became the final stop of his professional baseball career.

Greason was especially effective in Puerto Rico in the 1957-58 season. He was 12-6 with a 2.76 ERA and pitched 25 consecutive scoreless innings, a streak which was broken only after a start in which he had thrown 11 shutout innings.38 His career with the Crabbers concluded the following winter.

At Rochester in 1958, Greason was teamed with another future Hall of Famer, Bob Gibson, who has noted that Greason “took him under his wing.”39 Now an elder statesman, Greason was used primarily as a reliever and compiled a 16-18 record in his time with the Red Wings, before being traded to a team in Charleston, West Virginia toward the end of 1959. After contract negotiations with Charleston fell through, Greason retired with a career minor-league record of 78-62.

Upon his retirement, Greason moved back to Birmingham, which was his wife’s hometown. He had met his wife, Willie Otis, at Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, though the couple ended up being married by a Justice of the Peace in Mississippi in 1953.40 Rev. and Mrs. Greason celebrated their 63rd anniversary in 2016; they have two adult daughters, two grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

Baseball was still in Greason’s blood, and he pitched for an city-league team, Fairfield, with which he won a championship.41 He also had the opportunity to play against Jackie Robinson when Robinson brought one of his barnstorming teams to town. He allowed only one hit in the game, prompting Robinson to joke with Greason, “They didn’t come to see you. They came to see me.”42

Greason worked for 14 years in Pizitz Department Store. However, he felt called to the ministry and enrolled at Birmingham Easonian Baptist Bible College; after earning a degree in religion, he also completed post-graduate work there and at Birmingham’s Samford University. He had become a parishioner at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and, by 1963, was preaching there once a month.43 The church had become a meeting point for civil rights activists – including Greason’s childhood neighbor Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. – and was launched into the national spotlight on September 15, 1963. On that Sunday, four members of the Ku Klux Klan planted a bomb at the church that killed four young girls and injured 22 others, an act of terrorism that King called “one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity.”44

In a twist of fate, Greason was not in attendance at the church on the day of the bombing; he was in Tuscaloosa as part of an organization trying to get youths involved in organized baseball programs.45 He does remember the paroxysm of violence that gripped Birmingham after the bombing, saying, “We were angry – of course we were because they were using fire hoses on people. Then they brought dogs in like we were animals or something. That would anger anybody!”46

Birmingham had a reputation as the most segregated city in the entire United States, and its complete and stubborn resistance to any efforts toward integration has been called “mindless defiance.”47 Bombings were so common in the city – there had been 41 since 194748 – that the city’s critics had derisively dubbed it Bombingham. Never before had there been casualties, however, and the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church gave impetus to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Greason used his part-time pulpit to push for civil rights during those turbulent times, and he has continued to preach ever since. He started the New Hope Baptist Church in Bessemer, Alabama and, in 1971 he was installed as the pastor of Bethel Baptist Church of Berney Points in Birmingham.49 More than 45 years later, he is the senior pastor of the same congregation at the age of 92; as of January 2017, he still preaches every Sunday even after battling two serious health issues in 2014.50

In addition to his pastoral duties, Greason works with a non-profit foundation he co-founded in 2007, the American Negro League Baseball Association. The organization’s goal is to unite the remaining Negro League legends and to support a program called Project HELP – an acronym for History Entrepreneurs Leadership Program – which works “to leave a lasting legacy to the underprivileged children of the [Birmingham] community.”51 He has also put together a Museum of Legends, featuring notable community members as well as mementoes from his life in baseball, which is currently housed at Bethel Baptist Church. For his decades of community service, Greason was presented with a lifetime achievement award at the annual Alabama Black Achievement Awards Gala in 2011.

America has continued to grapple with its racial history, but in later life Greason also has received long-overdue recognition for his accomplishments prior to his ministerial career. On June 27, 2012, he was in Washington, D.C. as part of a group of 370 Montford Point Marines who received the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor. Two months later, on August 30, he was honored by the minor-league Oklahoma City Redhawks (now Dodgers) on the 60th anniversary of his breaking the color barrier in the state of Oklahoma. On September 21, 2014, the St. Louis Cardinals held a similar ceremony to commemorate the 60th anniversary of his debut as the franchise’s first African-American pitcher.

Greason has said about his life’s experiences, “I have no regrets. I thank God for the direction he led.”52 Far from simply having no regrets, he earned many reasons to be proud: as a U.S. Marine, pioneering baseball player, civil rights activist, pastor, husband, and father, Greason has become a quintessential American.

Last revised: April 19, 2017

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the endnotes, the author also consulted the following:

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003).

McNary, Kyle. Black Baseball: A History of African-Americans & the National Game (New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.), 2003.

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor. Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition, 2011).

Vance, Mike, editor, Houston Baseball: The Early Years 1861-1961 (Houston: Bright Sky Press, 2014).

Also, special thanks go out to the following:

Dr. Bill McCurdy and Mike Vance, fellow members of SABR-Houston’s Larry Dierker Chapter, who responded to my inquiries about Bill Greason’s time with the Houston Buffaloes. Their spirit of helpfulness is greatly appreciated.

Rory Costello, who took great interest in this biography and contributed both expert editing as well as his additional knowledge about Greason’s time in the Caribbean when it was first written for SABR’s Biography Project.

Bryan Steverson, author of Baseball: A Special Gift from God and a friend of Rev. Greason, who answered questions and was generous enough to offer his interview notes, which provided additional information that has resulted in a slightly expanded version of this article for this book.

Jorge Colón, a SABR member in Puerto Rico who is also that country’s league historian, for providing the picture of Greason from the 1954-55 Crabbers championship team’s photo.

Notes

1 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1995), 216.

2 John Klima, Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 62.

3 KTVIDScruggs and CNN Wires, “Cardinals first African American pitcher honored with Living Legend Award,” September 1, 2014, http://fox2now.com/2014/09/01/cardinals-first-african-american-pitcher-honored-with-living-legend-award/, accessed October 23, 2015.

4 Bryan Steverson, Baseball: A Special Gift from God (Bloomington, Indiana: Westbow Press, 2014), 238.

5 Nick Diunte, “Former Negro League pitcher Greason graciously shares his grand life story,” February 25, 2013, http://www.examiner.com/article/former-negro-league-pitcher-greason-graciously-shares-his-grand-life-story, accessed October 23, 2015.

6 Larry Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team And Its Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009), 172.

7 Bryan Steverson, Notes from Interviews and Conversations with Rev. Bill Greason, email from Bryan Steverson to this author, December 16, 2016.

8 Diunte, “Former Negro League pitcher Greason graciously shares his grand life story.” Official statistics from Greason’s season with the Nashville Black Vols are unavailable. Greason’s win-loss record stems from his own recollection of his time with the Nashville team.

9 Ibid.

10 The Grays played their home games at either Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field or Washington’s Griffith Stadium; however, both stadiums were being used by their major-league tenants at the time of the1948 Negro World Series.

11 “Grays Hold 3-1 Lead in Series,” Afro-American, October 9, 1948.

12 Negro Leagues Baseball Museum eMuseum, “William Greason,” http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/greason.html, accessed October 23, 2015.

13 Powell, 174.

14 Emmons Byrne, “The Bull Pen,” Oakland Tribune, April 3, 1951: 28.

15 “Pacific Coast League – Oakland,” The Sporting News, April, 18, 1951: 30.

16 “Big Negro League Tilt at V.F.W. Stadium Tonight,” Sikeston (Missouri) Daily Standard, June 28, 1951: 8.

17 Ibid.

18 Berry Tramel, “Oklahoma City’s Jackie Robinson: When Bill Greason integrated baseball here,” The Oklahoman, August 22, 2012, http://newsok.com/article/3703298, accessed October 23, 2015.

19 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947-1959 (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 111.

20 Derrick Goold, “Cards honor Greason, one of their trailblazers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 21, 2014.

21 Al Hirshberg, “Bosox Bid for Negro Hill Star, Greason, Also Sought by Yanks,” The Sporting News, December 24, 1952, 9.

22 Tramel, “Oklahoma City’s Jackie Robinson: When Bill Greason integrated baseball here”

23 Ibid.

24 John Cronley, “Negro Duel Makes Lone Star History,” The Sporting News, August 13, 1952, 31.

25 Ibid.

26 “Humphries Puts Price Tag at $75,000 Plus on Greason,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1952: 27.

27 “Oklahoma City Turns Down $50,000 Offers for Greason,” The Sporting News, January 28, 1953: 21.

28 Bob Broeg, “Cards, Reshuffling Hands, Get Texas Negro Ace in Deal,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1953: 11.

29 “One-Hitter for Nine Frames, Greason Bows in 15th, 2-1,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1954: 28.

30 Bob Broeg, “Ragged Pitching Grounds Rich-in-Hitting Redbirds,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1954: 9.

31 Klima, Willie’s Boys, 268.

32 Ibid.

33 Diunte, “Former Negro League pitcher Greason graciously shares his grand life story.”

34 Thomas E. Van Hyning,, The Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999), 63.

35 Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, 70.

36 Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, 253.

37 Lou Hernández, The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues, 1947-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011), 52. “Hoy 25 de Enero…en Béisbol Invernal Dominicano,” Lidom.com, January 25, 2014.

38 Moffi and Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: 111.

39 Goold, “Cards honor Greason, one of their trailblazers.”

40 Steverson, Notes from Interviews and Conversations with Rev. Bill Greason.

41 Powell, 179.

42 Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham, 180.

43 Ibid.

44 David J. Krajicek, “Justice Story: Birmingham church bombing kills 4 innocent girls in racially motivated attack,” New York Daily News, September 1, 2013.

45 Powell, Black Barons of Birmingham, 180.

46 KTVIDScruggs and CNN Wires, “Cardinals first African American pitcher honored with Living Legend Award”

47 Bruce Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of Minor-League Baseball in the American South (Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 245.

48 Adelson, Brushing Back Jim Crow, 246.

49 Steverson, Notes from Interviews and Conversations with Rev. Bill Greason.

50 Steverson, Notes from Interviews and Conversations with Rev. Bill Greason. Steverson noted that Greason had a pacemaker installed and had colon cancer surgery in 2014.

51 “American Negro League Baseball Association Project HELP,” Birmingham Times, August 14, 2014, http://www.birminghamtimes.com/2014/08/american-negro-league-baseball-association-project-help, accessed November 2, 2015.

52 Tramel, “Oklahoma City’s Jackie Robinson: When Bill Greason integrated baseball here.”

Full Name

William Henry Greason

Born

September 3, 1924 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.