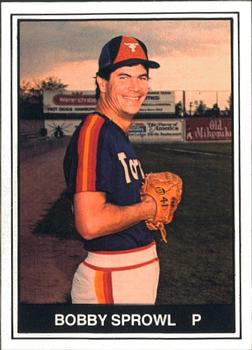

Bobby Sprowl

College baseball coach Bobby Sprowl’s teams have won more than 1,000 games in the course of a career that’s run 30 years and counting. He’s also run a successful baseball camp for the past 25 years.

College baseball coach Bobby Sprowl’s teams have won more than 1,000 games in the course of a career that’s run 30 years and counting. He’s also run a successful baseball camp for the past 25 years.

The left-handed pitcher was a second-round draft pick of the Boston Red Sox in 1977 and made it to the majors at age 22, appearing in parts of four seasons for the Red Sox and the Houston Astros.

He was born in Sandusky, Ohio, as Robert John Sprowl Jr. on April 14, 1956. The family lived in nearby Huron. “My parents were Bob and Lois Sprowl,” he said in a March 2020 interview. “My mom didn’t work and my dad worked for a while for Scott Paper Company. I don’t really know what he did for Scott. I was so young at the time. Then we moved to Tampa, Florida, and he had his own business. He did specialty things like pens, hats, calendars – stuff like that. With logos.”1

Young Bobby was in the second grade when the Sprowls moved to Tampa. “My mom’s parents bought a nice place down there and we’d go down there on vacation. I guess they decided we wanted to move down there, so we moved, I guess, when I was in about the second grade. I had one brother and I had four sisters. One of them passed away, so now I have three. Everybody seems to be in good health right now.”

He played both American Legion and high school ball in Tampa, attending Chamberlain High School – the same school where Steve Garvey had played about a decade earlier.

Sprowl was recruited by the University of Alabama and offered a scholarship. He attended college there, and has been living in the Tuscaloosa area ever since. “One of my American Legion coaches at the time left to be a graduate assistant up there. When I first played in the SEC…probably until [Mississippi State coach] Ron Polk came in, there weren’t a lot of out-of-state kids. I was one of the few out-of-state guys that we had on our team. Most of them were in-state kids. You could go to any of the schools back then and there were a lot of in-state players. My Legion coach took me up for a visit. We liked it and I ended up committing there.”

He told the Tuscaloosa News that the biggest influence on him growing up was his parents. “They always gave us all. I had health problems when I was younger and there’s no telling how much time they gave up to do stuff. My dad had his own business and he taught you how to work and be a leader-type person.”2

The problem was an eye problem, but one that didn’t interfere with his pitching, “a bad right eye to the point where I still can’t see too good out of it right now,” Sproul said in the 2020 interview. “Probably when I was coming up in high school, there were a lot of rumors that I had a glass eye, and this and that. I could see out of it, but not real good. My mom used to take me all the time to a specialist at the University of Florida. I’d seen specialists in Ohio. Nobody could figure out what was wrong.” Overall, though, his vision was fine. “I had a problem about a year and a half ago where I didn’t know if I was going to be able to coach again. I had, like, a hole in my retina in my left eye. Luckily, I had a good surgeon who fixed it and I’m 20/20 again.”

Bobby Sprowl pitched for the Crimson Tide, Alabama’s baseball team that has produced at least 67 major-league ballplayers. Sprowl was a second-team All-American and an All-SEC selection at Alabama in 1977, majoring in Criminal Justice. “Social work, criminal justice. That type of stuff. I don’t know that I would have gotten into it. I enjoyed being around kids. I liked that part of it. Back then, I was really just interested in playing baseball. I went to school to play baseball, and I got an education with it.”

Sprowl was the 39th pick overall in the 1977 draft, his signing credited to Red Sox scout Milt Bolling. It was no surprise the Red Sox picked him. With Alabama, he had just completed his junior year, leading the nation in K/9 (strikeouts per nine innings), whiffing 115 batters in 92 innings that year.3 The summer before, in 1976, he’d played in Boston’s backyard, pitching for the Wareham Gatemen in the Cape Cod Baseball League. He was given the league’s Outstanding Pro Prospect award. Working relief in the season’s final game, he had nailed down a win for Wareham, giving them their first league championship.4

The Red Sox sent him to their Single-A team in Florida, the Winter Haven Red Sox, and he appeared in 26 games, all but three in relief. One of the three starts he had was a shutout. Over his 60 innings of work, he struck out 64 batters and was 9-4 with a 2.10 earned run average.

Over the winter, he played a bit of baseball in the Dominican Republic and, when home, sometimes worked as a substitute teacher.

He joined the Red Sox for spring training in 1978 and that’s where he picked up a baseball-sounding nickname. “When I played baseball, my nickname was ‘Bullet Bob.’ I was probably the hardest thrower in the Boston organization, but I didn’t get that name because of my throwing. I got it when I was shot in the arm. At spring training, my wife and I were sleeping and a bullet went through the wall and hit me right in the arm, at about 4 A.M. It was serious at the time, but afterwards it was funny.”5 He was just grazed by the .22 bullet and it was his right arm that was hit, but clearly it could have been fatal. The Boston Herald reported, “Police said the bullet was fired through the wall of the apartment next door by a doctor who thought he heard prowlers.”6 The Boston Globe said the shot left a wound that was six inches long.7 In 2020, he described it now looking like what might appear to be a vaccination mark.

Sprowl began the season in Double A with the Bristol Red Sox. He worked 103 innings in 20 games (11 of them starts) and was 9-3 (2.71 ERA), with 102 strikeouts. At one point, he pitched back-to-back one-hit shutouts. This earned him a promotion to Triple-A Pawtucket in early July, where he worked another 78 innings with 69 K’s, a 7-4 record and a 4.15 ERA. He was promoted to the big-league club in the middle of a September pennant race.

There had been some discussion as to whether or not to bring him up. Boston manager Don Zimmer said, “If I were to bring him up, I’d want him to pitch. I don’t want any young pitchers sitting around.” The Boston Globe’s Larry Whiteside wrote that Sprowl “probably won’t be called up unless the club gives up on Bill Lee.”8

It wasn’t just a matter of giving up on Bill Lee. Zimmer and Lee came from two different cultures and there was no love lost between them. And there was drama. On August 24, Peter Gammons wrote that “the Bill Lee-Don Zimmer-Red Sox thing is now the longest-running show in Boston.”9 Lee, he informed readers, had just been pulled out of the rotation, with Zimmer shifting things around and saying he was going to bring up Sprowl – a left-hander like Lee – in September. Lee had gone from 10-3 to 10-10, losing seven decisions in a row after July 15. That said, his ERA was 3.52 at that point, average on a very good Red Sox team that finished with a team ERA of 3.54, and in four of the losses he had received just one or two runs in support.

The Red Sox had been riding high, in first place by seven games at the end of August, but come September 5 they’d lost four of their last five games and seen two games come off their lead. On September 1, Luis Tiant had to leave the game in the sixth due to a pulled groin.10 The bullpen was overworked. GM Haywood Sullivan put in a call to bring up Sprowl, to join the team in Baltimore.11 It was a tough task for a 22-year-old rookie, who’d been in Single A the previous year, to stop the slippage. Pawtucket manager Joe Morgan said that Sprowl “might not be ready for the big leagues.” Morgan said, “His problem is trying to throw the ball by too many guys.”12

Sprowl’s opponent in his September 5 debut was future Hall of Famer Jim Palmer, who already had 17 wins in 1978 for the fourth-place Orioles. The Sox lost, 4-1.

It wasn’t just Sprowl, of course. The Red Sox scored only once.

The Red Sox scored first, one run in the top of the second when Carlton Fisk singled and Dwight Evans doubled him home. Sprowl pitched masterfully through six. He gave up a single to the first batter he faced, Kiko Garcia, who then stole second. He then retired the next three batters on a fly ball and two groundouts. He walked a batter in the second, gave up a single in the fourth, and walked another batter in the bottom of the sixth.

In the bottom of the seventh, though, Lee May homered to lead off the inning, the ball ticking off Jim Rice’s glove and over the fence.13 Andres Mora reached second when his grounder skipped through the legs of third baseman Butch Hobson for an error. Carlos Lopez singled pinch-runner Mark Dimmel home, and the O’s had a 2-1 lead on the unearned run. Zimmer had Sprowl start the eighth, but after a walk and a single, he brought in Dick Drago to relieve his starter. Drago got two outs, but then a double brought in both baserunners and Sprowl was saddled with a 4-1 loss.

Sprowl said that before the game he’d been nervous, but not when he got to the park. He complimented Fisk on calling a great game; he only called off Fisk a couple of times when Fisk wanted a changeup. “I didn’t have confidence in it after I almost threw one away early in the game.”14 Zimmer said that, even before the game, he’d written Sprowl in to start against the Yankees on Sunday at Fenway.

With the loss, Boston Herald sportswriter Tim Horgan noted that the team had been playing just a bit better than .500 ball since the All-Star Break (.519). “The Red Sox are fading like my summertime tan,” he wrote, telling readers it was OK to push the panic button.15 The Sox had had a nine-game lead for first place at the break. The New York Yankees were now only four games behind in the standings – and they were coming to Boston for a four-game stretch.

By the time Sprowl got the ball on the Sunday, the Red Sox had won once (Tiant’s shutout) but then lost games to the Yankees on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Their lead in the AL East was down to just one game. The Yankees had won 15 of their last 17 games. Pressure or anything? If Sprowl glanced at the Boston Globe that morning, he might have seen what Peter Gammons wrote, “[A]ll that stands between the New York Yankees and first place is Bobby Sprowl.”16

On September 10, Sprowl walked the first batter, saw him steal second, then walked the second batter. A double play offered immediate hope, but then Reggie Jackson singled in the runner from third. Sprowl walked the next two batters, too, loading the bases, and Zimmer called on Bob Stanley to relieve the rookie. Two baserunners scored on a single, and the Red Sox never caught up, losing the game, 7-4, with the loss charged to Sprowl. He had given up one hit, but walked four. Red Sox relievers gave up 17 more hits (all of them singles) before the game was over. The Yankees were apparently not to be denied.

After the game, Zimmer said of Sprowl, “He couldn’t get the ball over for strikes. I’ll say this for him. Fisk said he was missing low. That’s better than missing high.”17 Zimmer was faulted by many for starting Sprowl rather than Tiant (on three days’ rest), in what seemed to many a crucial game. The four losses in a row to the Yankees promptly became known as the Boston Massacre.

Sprowl only pitched in one more game for the Red Sox, eight days later in Detroit. He started and worked five innings, giving up a couple home runs, before departing with the Red Sox ahead, 4-3. He was in line for a win until Steve Kemp banged a game-tying homer off Bob Stanley in the bottom of the eighth. The Red Sox rallied, but the win came in the 11th inning and went to Andy Hassler.

The Red Sox and Yankees battled to a 99-63 tie at season’s end. The Red Sox had to win their last eight games to manage the tie, but they lost a single-game playoff at Fenway Park – the game known as the Bucky Dent game.

Sprowl came to spring training rested and hoping to win a spot on the Red Sox staff. He took a room in the Holiday Inn, rather than the duplex apartment where he’d been hit by a bullet the year before.

There were problems. He was said to have been wild in batting practice, and then in his first appearance (March 13), he faced only five batters, throwing one wild pitch, walking four, and giving up a single. Bill Liston wrote in the Herald that Sprowl had “misplaced any knowledge he ever had of the location of home plate.”18 Pitching coach Al Jackson reminded reporters that Sprowl was pretty green. Sprowl himself said he was aiming the ball. “I haven’t got any rhythm. Sometimes I release the ball behind my body, sometimes ahead. I’m hesitant to even throw the ball.”19 A few days later, he was assigned to the minor leagues. Peter Gammons sympathized with his plight: “Certainly the most disturbing aspect of spring training was what happened to Bobby Sprowl. When he came up last September, people said he had poise, ice water in his veins. Well, he isn’t a self-confident young man and is not blessed with the social self-confidence of most athletes. The Yankee start haunted him all winter, and when he began to have control problems in batting practice, the impatience of his veteran teammates helped bury him. Sprowl is a great kid and an exceptional talent. I hope he gets it all back.”20

Sprowl was ready to put in the work. “There isn’t anything wrong with my arm,” he said. “The reason I didn’t make the team was all in my head. I didn’t have the faintest idea what I was doing as far as releasing the ball. Now I’m going to go down to Pawtucket and get my head together, get my rhythm back.”21

He was placed in Single A, with Winter Haven, and struggled there; he was 3-6 with an ERA of 3.67, though he struck out 88 batters and only walked 31 in 76 innings. He was 0-1 for Pawtucket. On June 19 he was the player to be named later completing a June 13 trade with the Houston Astros, which brought Bob Watson to Boston. Houston placed him with the Triple-A Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies.

For the 1979 and 1980 seasons, Sprowl was again a September pitcher in the big leagues. After the minor-league season, he appeared in three games for the Astros on September 7, 12, and 30. He faced 14 batters and allowed just one base hit and no runs. He walked two.

But he had indeed struggled. “I went to spring training after Boston and got what they called the ‘yips.’ I couldn’t throw the ball in the batting cage. When I came back…I’m probably one of the few guys that had it and still pitched a little bit in the major leagues. My stuff dropped off just a little bit. I probably didn’t throw as hard, and the life wasn’t there. After a while, it got frustrating and embarrassing. You’re trying to look for gimmicks to try and figure out how to do it again. People who haven’t had it, they don’t understand it. It’s a mental thing that comes on, just out of nowhere.”

He worked in the Pacific Coast League for the Astros-affiliated Triple-A Tucson Toros during the 1980 season, starting in 25 games and relieving in one. His record was 10-11 (4.35) with 89 strikeouts and 79 walks. Called up to Houston once more at season’s end, he worked just one inning, against the Padres on September 23. He allowed a triple and walked a batter, but struck out three.

In 1981, he “caught Manager Bill Virdon’s eye” in the spring and was on the 25-man Astros roster when the team broke camp.22 He got into his first game on April 20, was asked to get one batter, and struck him out. He worked eight games in May, all but the May 14 game in relief, with just one decision – a loss. After June 9, with a 5.40 ERA, he missed more than two months (as did all of major-league baseball) due to a players’ strike. Once the games resumed, he didn’t work much – four innings in August, two in September, and one in October. He finished the season 0-1 (5.97).

They were his last innings in the majors.

In 1982 and 1983, he divided his time between the Double-A Columbus (Georgia) Astros and Triple-A Tucson Toros, with most of the time in both seasons spent with Columbus. He relieved most of the time in both years. His records with Columbus were 5-3 (2.79) and 6-2 (4.47), respectively. With the Toros, he was 0-3 in 1982 and without a decision in 1983.

On December 21, 1983, the Astros traded him to the Baltimore Orioles for left-handed reliever Craig Minetto. Sprowl was placed on Rochester’s roster, but never pitched in a regular-season game for them. Instead he saw duty in 1984 with three other teams. Released on April 5, he signed with Double-A Birmingham (Detroit Tigers affiliate) on April 28, but only appeared in 4 1/3 innings over five appearances and was released on May 11. He signed with the Florence Blue Jays (in the Single-A Sally League) on June 2 and was 1-0 in four appearances. He was released to Kinston (Carolina League), another Single-A team in the Toronto system, on June 15. Despite a decent 3.97 ERA, he was 1-5. At the end of the season, he became a free agent on October 15.

It was a pretty seamless transition to his post-playing career. He started work at Shelton State Community College in 1986, and except for a four-year stretch when he was assistant coach at the University of Alabama, he has stayed put at the two-year Tuscaloosa-based community college. He says he enjoys working at a two-year college because “every year it’s a new team.” And he takes a personal interest. “I always try to treat these boys like they’re my own son.”23

“Shelton State, where I teach now, had just started a baseball program that year and it was a matter of…I think Toronto came in to watch somebody at Alabama and the guy asked me if I wanted to give it one more shot. So I went out and played in their organization for a minute, or until the end of the year. It just got to where I didn’t know if I’d ever solve the problem, whether I could throw strikes on a consistent basis like I used to. Shelton State started their program and I sort of helped in the offseason and the guy who started it just stayed one year and I sort of jumped in and took over after that. Really, I’ve been coaching since.

“So I got to stay around baseball all the time. Got to see a lot of people that you grew up playing against, as scouts or coaches or whatever. I’ve been coaching now for I guess about 35 years.”

And in that period of time, his teams have won over 1,000 games, reaching the mark on March 30, 2019. In 2012, he was named the ACCC Coach of the Year, after leading Shelton State to the Junior College World Series in four of the previous eight seasons. Two years earlier, in January 2010, Sprowl was inducted into the Alabama Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame during a ceremony in Montgomery. He said at the time, “I’m not big into the awards, but I think this is an honor for being around the game for so long and watching it change and having so many good players. It’s not anything I’ve done. It’s pretty much the players going out and playing.”24

For many years, he has also run a series of summer baseball camps. “We run about 600 kids through each year. I do a couple of them where I go out with them to towns around Alabama, and then I do four or five at home. We usually get about 100 kids a week.”25

Bobby Sprowl has been married twice. His first marriage was to Beverly Wiggins on December 29, 1977. “I had just signed and after the instructional league the Red Sox had asked me to go down to the Dominican Republic. I came back and got married.” The marriage lasted about eight years. “We had a son and he ended up playing pro ball. Signed with the Cubs. Somehow he ended up being traded to the Yankees. He made it up to Triple A for just a little while.” Jon-Mark Sprowl was “a pretty good contact-type hitter that could hit, and they tried to convert him into a catcher.”26

A second marriage, to Teresa Gibson, produced two children. a daughter and a son, Trevor, an infielder who signed with the Braves and played briefly in the low minor leagues.27

Teresa Sprowl also works at Shelton State, where they first met, though she works at a different location. “We have two different campuses. She’s sort of a supervisor at the other campus – not the boss, but one that everybody looks to. She’s an important part of her campus.

“Baseball’s no big deal to her. The only time she came and watched was when her son was playing. Which is good with me. Sometimes people are rude out in the bleachers. They’ll say stuff without even thinking. At least she doesn’t have to listen to that.”

Looking back on his pro career, it would be only natural to think about how things might have worked out differently. He said, “You often wonder what would have happened, had I not gotten the yips. Most of the times when I lost games, it wasn’t because of the yips. I just wasn’t fortunate enough to win a game. I had some chance to win games and part of it’s probably my fault and part of it’s just that things didn’t go right.”

The first game he lost was a 4-1 game. You can’t win without run support. “That’s baseball, though. That part doesn’t bother me as much as when you really struggle going out there and you deserve to lose. You just do the best you can. I don’t look at records or anything like that and say, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t win a game.’

“People said that I got rushed to the big leagues. Maybe I was. Maybe I wasn’t. But that didn’t have an effect on anything. I signed in’77 and was up in ’78 but my troubles didn’t really start until spring training of the next year. Not that I was great down the ‘78 stretch, but I hate for somebody to say, ‘They ruined his career.’ You don’t know what would have happened. The same thing could happen to anybody. It could have happened two years from then. You just don’t know. For some reason it happened. I don’t blame anybody for losing the control like I did. Nobody could foresee anything like that. I don’t think I was rushed. I always was a competitor. It’s not like I was intimidated.

“I don’t blame Don Zimmer for any of my problems. I enjoyed my time in Boston. I’m still a Red Sox fan. Of course, we get the Braves down here so I end up watching them some. I feel bad that I couldn’t win a game to get us to not having to play in that playoff game, but it just didn’t happen. It was just baseball – sometimes when you hit, you don’t score, and when you score you don’t pitch. Teams go through that and we just happened to go through it towards the end.”

Last revised: June 16, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by James Forr and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Mark Sternman.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. Thanks to Rod Nelson and the Boston Red Sox.

Notes

1 Author interview with Bobby Sprowl on March 22, 2020. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations come from this interview.

2 Kim Eaton, “Bobby Sprowl, Shelton State Baseball Coach,” Tuscaloosa News, December 5, 2012. https://www.tuscaloosanews.com/article/DA/20121205/Entertainment/605157492/TL/

3 “Bobby Sprowl,” Bristol Red Sox. http://www.bristolredsox.com/roster/sprowl_bobby.php

4 “Wareham Takes Cape League Championship,” Cape Cod Register, September 2, 1976. http://digital.olivesoftware.com/Olive/APA/Yarmouth/SharedView.Article.aspx?href=DPLTR%2F1976%2F09%2F02&id=Ar02205&sk=C2BC9444&viewMode=image. Accessed January 24, 2020.

5 Kim Eaton.

6 Jack McCarthy, “Errant Bullet Grazes Sleeping Sox Southpaw,” Boston Herald, March 26, 1978: 5. The doctor was not arrested.

7 Peter Gammons, “Sox Rookie Wounded By Bullet While Asleep,” Boston Globe, March 26, 1978: 79. He apparently shouted out, “I’ve been shot” and his wife Beverly thought he was having a nightmare and told him to go back to sleep. He missed three days of work while the wound heeled. Throughout the year or more that followed, his name immediately triggered responses in people that heard it. He was “the guy who got shot.” He said he was resigned to becoming something of a footnote in Red Sox lore. See Bob Ryan, “The Kid in Bristol Is Sharp As A Pistol,” Boston Globe, June 30, 1978: 54, 55.

8 Larry Whiteside, “Zimmer, Sullivan Plot Strategy for the Stretch Drive,” Boston Globe, August 22, 1978: 31. The Zimmer quote comes from this same article.

9 Peter Gammons, “The Manager and the Lefthander,” Boston Globe, August 24, 1978: 17.

10 Tiant didn’t miss a turn, though, and threw a two-hit shutout on September 6.

11 Gerry Finn, “A’s Beat Sox with Homers, 5-1,” Springfield Union (Springfield, Massachusetts), September 2, 1978: 17.

12 Peter Gammons, “Sprowl Gets the Call from Sox,” Boston Globe, September 2, 1978: 17.

13 Peter Gammons. “Sox Falls to Orioles Again, 4-1 As Lead Shrinks to Four Games,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1978: 25.

14 Larry Whiteside, “Is This the Lefty the Sox Are Seeking?,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1978: 25.

15 Tim Horgan, “Close Your Eyes, Make A Wish, and Panic….” Boston Herald, September 6, 1978: 35.

16 Peter Gammons, “Rampaging Yankees Cut Sox Lead to 1,” Boston Globe, September 10, 1978: 45.

17 Larry Whiteside, “The Yanks Have Landed,” Boston Globe, September 11, 1978: 25.

18 Bill Liston, “Sprowl’s A Wild Man,” Boston Herald, March 14, 1979: 33.

19 Bill Liston, “Sprowl’s A Wild Man.”

20 Peter Gammons, “Play hurt? Fisk Always Has…,” Boston Globe, April 1, 1979: 57.

21 Bill Liston, “Sprowl’s Wildness All in His Head,” Boston Herald, March 25, 1979: 40.

22 United Press International, “Richard Deactivated, Houston Trims Roster,” Galveston Daily News, April 3, 1981: 18.

23 Kim Eaton.

24 Andrew Carroll, “Former UA Baseball Players Enter ABCA Hall of Fame,” Tuscaloosa News, January 26, 2010. https://www.tuscaloosanews.com/article/DA/20100126/News/606109583/TL .

25 Author interview, March 2020. For an article about Sprowl and the camps, see Jeff Edwards, “Sprowl Baseball Camp an Athens Tradition,” News-Courier (Athens, Alabama), June 15, 2018, at https://www.enewscourier.com/sports/local_sports/sprowl-baseball-camp-an-athens-tradition/article_6087de46-7025-11e8-9ad4-f734fe3cc90c.html .

26 Author interview, March 2020. Jon-Mark Sprowl’s record can be found on baseball-reference.com: https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=sprowl001jon .

27 Trevor Sprowl’s career is found at: https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=sprowl000tre .

Full Name

Robert John Sprowl

Born

April 14, 1956 at Sandusky, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.