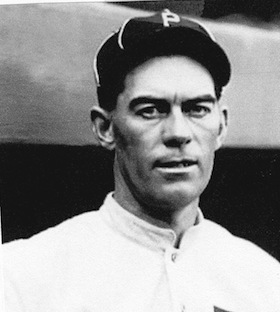

Jimmy Lavender

Although his contract rights were several times acquired by major-league clubs, Deadball Era right-hander Jimmy Lavender never received much chance to demonstrate his worth – until misapprehension of minor-league draft rules left the Chicago Cubs with little other choice. Once given the opportunity, Lavender quickly established himself as a competent major-league hurler, eventually putting two memorable victories over the New York Giants onto his résumé. In July 1912 he brought Rube Marquard’s celebrated 19-game winning streak to an end, besting the future Hall of Famer, 7-2. Three years later, Jimmy threw a no-hitter at New York. Key to these triumphs, and to Lavender’s professional success, was his mastery of a single pitch: the spitball.

Although his contract rights were several times acquired by major-league clubs, Deadball Era right-hander Jimmy Lavender never received much chance to demonstrate his worth – until misapprehension of minor-league draft rules left the Chicago Cubs with little other choice. Once given the opportunity, Lavender quickly established himself as a competent major-league hurler, eventually putting two memorable victories over the New York Giants onto his résumé. In July 1912 he brought Rube Marquard’s celebrated 19-game winning streak to an end, besting the future Hall of Famer, 7-2. Three years later, Jimmy threw a no-hitter at New York. Key to these triumphs, and to Lavender’s professional success, was his mastery of a single pitch: the spitball.

James Sanford Lavender was born on March 26, 1884, the oldest of five children born to James Stapler Lavender Jr. (1861-1929), and his wife, the former Annie Laurie Mitchell (1862-1958).1 Sources differ regarding his place of birth. Modern reference works like Baseball-Reference.com state that Jimmy was born in Barnesville, Georgia,2 a bustling county seat located about 60 miles southeast of Atlanta. But contemporaneous sources indicate that Lavender was born in Montezuma, Georgia, the small cotton-growing town where he was raised and lived most of his life.3 Whatever his actual birthplace, Jimmy, the son of a prosperous lumber mill owner, was raised in comfortable circumstances and educated in Montezuma schoolrooms until he was about 15. Then he was packed off to Gordon Institute, a military academy located a county away in Barnesville.

As with his birthplace, sources disagree regarding when Lavender first took interest in baseball – probably because Jimmy himself was inconsistent on the subject. In September 1912 he told [then] sportswriter Robert Ripley that he had begun playing with his “little chums around Montezuma’s back lots … and that he played early and often.” Had it not been for his father’s insistence that he put time in at the mill, Jimmy “probably would not have stopped my ball game to work anymore than he would have stopped to eat or sleep.”4 Interviewed two months later, however, Lavender professed youthful indifference to the game, informing F.C. Lane that as a boy in Montezuma “he neither handled a baseball nor swung a bat.” During his later time at Gordon Institute, Lavender was strictly a football player, and “while light, he played fullback from the first and was a uniformly daring and brilliant player.”5 Lavender split the difference when speaking to Atlanta sportswriter Percy Whiting, stating that he had played some baseball while in prep school, but was not a “regular pitcher for the Gordon team, but worked in some games.”6

After graduating from Gordon Institute, Jimmy enrolled as a civil engineering student at Georgia Tech, but completed only his first year. While there, he played no intercollegiate baseball, but reportedly pitched for his class team in intramural contests.7 Upon leaving college, Jimmy began pitching in earnest, often as a sort of hired gun for amateur and semipro teams in southern Georgia. Somewhere along the way, Lavender developed his out-pitch, the spitball. According to Jimmy himself, his spitter was self-taught, derived entirely from “written accounts I read of the way [Ed] Walsh and other twisters handled the ball,” experimentation, and practice.8 He entered the professional ranks as a 22-year-old in 1906, signing with the Cordele club in the Class D Georgia State League. The league disbanded in early July, but not before Lavender had cut an impressive swath through opposing teams. On Opening Day he posted a two-hit, 11-1 victory over Albany.9 He then reeled off seven more wins until Americus defeated “the mighty Lavender” on June 4, 7-1.10 Jimmy would not suffer another defeat in Georgia State League play, his record standing at 11-111 for a fourth-place (24-24) Cordele nine when the circuit ceased operations. Lavender then joined the Augusta (Georgia) Tourists of the Class C South Atlantic League, appearing in six games with no surviving record.12

Augusta released Lavender before the start of the 1907 season.13 He then signed with the Danville Red Sox of the Class C Virginia League, where his professional career gained traction. In a league-leading 59 appearances, Lavender went 18-16, with a 2.21 ERA and 196 strikeouts in over 300 innings pitched, for a second place (67-58) Danville club, and attracted major-league interest. Jimmy was among the recruits stockpiled sight-unseen by Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s, and thereafter optioned, without being given a pitching trial, to Holyoke of the Class C Connecticut League. Upon first meeting him in-person several years later, Mack expressed surprise at Lavender’s 5-foot-11, 165-pound size. Mack had been under the impression that Jimmy was “not over 5 feet 6 inches tall and didn’t weigh over 130 pounds. … If I had understood things in their true light,” Mack would not have jettisoned Lavender so hastily.14 In any event, Lavender spent the 1908 season in Holyoke, where history repeated itself. He turned in a fine 21-17 record, with a 2.68 ERA and 155 strikeouts in 272 innings pitched for a noncontending (60-66) Holyoke club, and was again drafted by a major-league club, this time the Boston Doves. But once again, Lavender was released without being given a trial in the big leagues, sold to Providence of the Class A Eastern League in January.15

Lavender spent the next three seasons in Providence, pitching well but with deceptive sub-.500 won-lost records. In 1909 he endured an “exceptional run of hard luck games,”16 posting a 14-17 mark, with a 2.18 ERA in 244 innings pitched, on a contending (80-70) Providence club. The quality of Lavender’s pitching did not go unnoticed, with Sporting Life reporting that he was likely to be acquired by the Detroit Tigers at season’s end.17 When Detroit passed over him, Lavender returned home to Montezuma to visit his mother and sisters. Thereafter, he was expected to play winter ball in New Orleans, in preparation for an anticipated spring 1910 tryout with the A’s.18 When Philadelphia declined to draft him, Lavender returned to Providence for another frustrating season. Pitching for a last-place Grays nine, Jimmy went 15-22, with a fine 2.00 ERA in 314 innings pitched. The following year, Lavender was better (19-22, with a sparkling 1.79 ERA in 339 innings) for another last-place (54-98) Providence team.

It appeared that Jimmy’s minor-league apprenticeship had finally come to an end when the Chicago Cubs drafted him near the close of the 1911 season. But almost immediately thereafter, the Cubs dispatched Lavender to another minor-league club, the Montreal Royals. The move prompted a protest by Detroit Tigers president Frank Navin, who had recently bought the Providence franchise of the newly christened Double-A International League.19 Navin maintained that Draft Rule 42 required the return of Lavender to Providence if the major-league club that drafted him (Chicago) chose not to retain his services. The National Commission agreed, issuing a January 1912 order that: (1) declared that the transfer of Lavender to Montreal was illegal; (2) directed the return of Lavender to the Cubs, and (3) commanded Chicago to retain Lavender on the Cubs roster for one year or return him to Providence.20 Shortly thereafter, Chicago club president Charles Murphy tendered Lavender a Cubs contract for the 1912 season. At age 28, Jimmy Lavender would finally get a bona fide shot in the big leagues.

Lavender made his major-league debut on April 23, 1912, inserted into a losing cause against Pittsburgh to face Honus Wagner. After he had retired Wagner and completed his two-inning relief stint unscathed, Lavender asked manager Frank Chance why he had sent in an untested rookie to face the fearsome Wagner. “There was no reason waiting all season to find out what you had in the way of nerve and ability,” was Chance’s brusque reply.21 Given his first start a few days later, Lavender carried a lead late into the game before his own throwing error triggered a winning Cincinnati rally. Jimmy had to wait a month before posting his first major-league victory, an 8-4 win over Cincinnati on May 30. After another month had passed without a second win, Lavender suddenly became untouchable. He posted three consecutive shutout victories, and took a 33-inning scoreless streak into the most momentous game of his career: a July 8 matchup against Rube Marquard of the New York Giants. Marquard had won his first 19 decisions of the season, and was now on the verge of establishing a new major-league record for consecutive victories. Lavender was the better man that game, bringing the Marquard victory skein to a close with a 7-2 victory over the Giants. For a brief time, the win turned Lavender into a baseball celebrity, the new face featured in a rash of sports columns.22 There was even a column on the Giants’ 1912 pennant chances syndicated under a Jim Lavender byline.23 Back at the ballpark, Lavender finished the season in good form, going 16-13, with a 3.04 ERA in 251? innings pitched for the third-place (91-59) Cubs.

Lavender got off poorly in 1913, dropping an Opening Day start against St. Louis, 5-3. Two months later his record stood at 1-6 and Lavender was in danger of being released. He managed to string together some good starts thereafter, but overall, Lavender’s performance regressed from his rookie year. His 10-14 record included a rise in ERA to 3.66 and alarming control problems. In 204 innings, Lavender issued 98 walks and hit a league-leading 13 opposition batsmen, while he struck out only 91. He recovered form somewhat the following season, going 11-11 with an improved 3.07 ERA in 214? innings pitched for a mediocre (78-76) Cubs team. His walks (87) and HBP (11) totals remained cause for concern, as was a late-season on-field embarrassment. During a September 23 game against the Phillies, Lavender was caught doctoring the baseball with an emery board attached to his uniform pants leg. He got off with an inconsequential $5 fine, but the incident bespoke a deficit in the Lavender pitching repertoire. Apart from his spitball, Jimmy possessed only a serviceable fastball and had no curve to speak of. He was, in brief, a pitch short of what was needed to become a top-flight big-league hurler.

The 1915 season was preceded by the signal event of Jimmy Lavender’s personal life. In February he married 24-year-old Aline Galloway of Mount Airy, North Carolina. Their union would last until Aline’s death some 29 years later, but produce no children. The ensuing baseball campaign was mostly a dreary one for Lavender, save for an August 31 outing against the Giants. For nine innings Jimmy was literally unhittable, with only a seventh-inning walk to New York first baseman Fred Merkle marring an otherwise perfect game.24 The 2-0 no-hitter was the highlight of a 10-16 campaign hampered by an early-season injury. Jimmy suffered a broken rib trying to get out of the bathtub25 and was out of action for almost a month. The following season was much the same for Lavender. In a reduced 188 innings, he went 10-14 for a noncontending (67-86) Cubs team.

In the offseason, a rebuilding Chicago club decided to shop Lavender. Philadelphia Phillies manager Pat Moran had long coveted Lavender and sent 19-game winner Al Demaree to Chicago in exchange for the spitballer.26 Placed in a formidable rotation that featured future Hall of Famers Grover Alexander and Eppa Rixey, Lavender began the season well. In his Phillies debut, he posted a five-hit complete-game win over the Giants. Later, he savored a relief victory over the Cubs. But by late May, the 33-year-old had faltered, and he received only intermittent starting assignments as the season wore on. On October 3, 1917, Lavender went five innings in a losing effort against the Giants. The defeat reduced his season record to 6-8 in 28 appearances for the Phillies – the final games of Jimmy Lavender’s major-league career. In December Lavender announced his retirement from baseball.27 In 224 major-league games spread over six seasons, Lavender had posted a 63-76 (.449) record, with ten shutouts. In 1,207? innings pitched, he held opposing batsmen to a .249 batting average, but his effectiveness had been compromised by control problems: his combined walks/HBP total (503) nearly equaled his 547 strikeouts. Despite that, his career 3.09 ERA was more than respectable. In all, Jimmy Lavender had been a competent, if not outstanding, major-league hurler.

Although the Phillies did not offer Lavender a contract for the 1918 season, the club advertised that the rights to the spitballer were available for $1,000.28 The interest of Pacific Coast League clubs was dampened by Lavender’s refusal to travel to the West Coast, and rumors that Cincinnati intended to acquire him prove unfounded. But Lavender was disposed to continue pitching, but only if assigned to a club somewhere near his home. And he expressed particular interest in playing for the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association.29 When a transfer to Atlanta could not be worked out, Lavender again declared that he was “through with baseball for all time.”30 Rather than pitch, Jimmy would do his bit for the war effort by putting in a full crop on the farm in Montezuma.31

Lavender resisted the urge to return to the diamond until 1922. Then, he began pitching for semipro teams in Dawson and Arlington, Georgia.32 Impressive work led to his signing by the Atlanta Crackers in late July.33 Jimmy’s return to the professional ranks lasted one game. He pitched decently in a rain-shortened 2-1 loss to Mobile, but quit the club immediately thereafter.34 He did not abandon the game entirely, however. A month later, Jimmy was pitching for a semipro team in Marshallville, Georgia.35 But that is the last trace of Lavender diamond activity found by the writer.

With his baseball days behind him, Jimmy Lavender slipped into the anonymity of private life. By 1930 he and wife Aline had left the family farm to take up lodgings elsewhere in Montezuma. Jimmy worked in supervisory capacities at various local mills and plants, and took in an occasional Atlanta Crackers game. In June 1944, Aline Galloway Lavender died.36 About that same time, Chicago newspaperman turned pulp fiction writer Vincent Starrett introduced readers to Jimmie Lavender, a cultured private detective loosely patterned upon Sherlock Holmes. Reportedly, Starrett sought and obtained the old spitballer’s permission before naming his new creation.37

Later in life, Lavender took a job with the Georgia State Highway Department. He was living in retirement in Cartersville, Georgia, when stricken by a fatal heart attack on January 12, 1960. He was 75. Following funeral services, James Sanford “Jimmy” Lavender was interred in Felton Cemetery in Montezuma. Survivors included his sisters Genevieve Lavender Timberlake and Lila Belle Lavender Smith, and his half-sister Annie Gertrude Lavender McCullar.

Notes

1 Sources for the biographical data provided herein include the Jimmy Lavender file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; family information accessed via Ancestry.com, and various of the magazine/newspaper articles cited below, particularly “James Lavender: A New Star from the Cotton States,” by F.C. Lane, Baseball Magazine, Vol. 10, November 1912. Jimmy’s younger siblings were Genevieve (born 1888), twins Lila Belle (1891) and Jack (1891-1896), and Bonita (1892-1914). He also had an older half-sister named Annie Gertrude (1883-1966) via his father’s liaison with a woman named Jimmie Ross.

2 The Giamatti Research Center player questionnaire completed after Jimmy’s death by his sister Lila Belle Lavender Smith states that Lavender was born in Barnesville. Jimmy’s late grandfather, James Stapler Lavender, Sr., (1829-1881) was a man of property in Barnesville, and, if the birthplace is accurate, Jimmy may well have been born at the Lavender family home there.

3 During Lavender’s lifetime, all published accounts about him stated or implied that he was born in Montezuma. See, e.g., Lane: “James Lavender was born at Montezuma, Ga., 26 years ago,” 62; an unidentified circa 1913 news article titled: “James Lavender, Pitcher of the Chicago National League Club,” in the Lavender file at the Giamatti Research Center; it begins, “James Lavender, the successful young spit-ball pitcher of the Chicago Cubs, was born just 27 years ago in Montezuma, Ga.” See also the James Sanford Lavender entry in the 1959 second revised edition of The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, by Hy Turkin & S.C. Thompson, which gives the Lavender birthplace as Montezuma, Ga. The designation in current baseball reference works of Barnesville as his birthplace originates with the circa 1961 player questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame by Jimmy’s sister, Lila Belle Smith.

4 “Georgia Boy’s Work Has Kept the Cubs Up in the Race,” by Robert Ripley, unidentified September 1912 news column contained in the Lavender file at the Giamatti Research Center.

5 Lane, 62. Although now a major leaguer, Lavender declared, “I always liked football much better than baseball, and I believe I do yet.”

6 “Beating Marquard Makes Georgia Boy a Hero; Crackers Have a Big Boost for Jimmy Lavender,” by Percy H. Whiting, The Atlanta Georgian, September 1912.

7 Whiting, “Beating Marquard.” See also “Pitcher Lavender of the Cubs Earns Soubriquet ‘Iron Man’ in East,” by I.E. Sanborn, Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1912.

8 Lane, 64. See also, “The Rookie Who Stopped Marquard’s 19-Win Streak,” by Jimmy Jones, Baseball Digest, Vol. 26, No. 3, April 1967.

9 As per the Columbus (Georgia) Daily Enquirer, May 4, 1906.

10 As per the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, June 5, 1906.

11 No statistics for the 1906 Georgia State League survive. Lavender’s record of 11-1 was compiled by the writer from news accounts and line scores of league play and may be incomplete.

12 Per the Lavender career record compiled by baseball historian Bill Deane contained in the Lavender file at the Giamatti Research Center. Contemporaneous accounts state that Lavender pitched a shutout against Jacksonville in his only Sally League appearance of 1906. See e.g., Lane, 63.

13 As per Sporting Life, April 11, 1907.

14 Lane, 63.

15 As per Sporting Life, January 23 and 30, 1909.

16 Sporting Life, September 18, 1909.

17 Sporting Life, July 31, 1909.

18 According to Sporting Life, October 23, 1909.

19 The former Eastern League received a name change and a status upgrade in December 1911. Lavender was intended to serve as compensation for the Cubs draft of Montreal outfielder Ward Miller earlier in the year.

20 National Commission Decision No. 851, reported in Sporting Life, February 3, 1912.

21 As recalled by Lavender years later. See Baseball Digest, Vol. 26, No. 3, November 1967.

22 See e.g., the Robert Ripley, Percy H. Whiting, and F.C. Lane articles cited above.

23 See “Pitcher Jimmy Lavender of the Cubs, Who Does Not Fear McGraw’s Teams,” an unidentified July 1912 column contained in the Jimmy Lavender file at Cooperstown. In the column, Lavender (or his ghostwriter) sniffed that he found New York “quite easy” to beat and predicted that “the Giants will not win enough games to come home 1912 pennant winners.” Two months later, the 103-48 New York Giants captured the NL flag by ten games over Pittsburgh.

24 At the time, there was widespread belief that the Giants were patsies for Lavender. See, e.g., “Lavender Is Veritable Giant Killer, Having Beaten Them 15 Times in 5 Years,” by Jim Nasium (Philadelphia sportswriter Edgar Forrest Wolfe), an unidentified 1917 article in the Lavender file at the Giamatti Research Center. According to the article, Lavender lost “just two verdicts to New York ball clubs” through the 1917 season. In fact, Lavender was hardly any kind of Giants-killer. He posted a losing 12-16 record against New York during his six-year major-league tenure.

25 New York Times, April 20, 1915.

26 As reported in Sporting Life, January 27, 1917, and elsewhere. Several months later Chicago sent $5,000 to Philadelphia to complete the Lavender-for-Demaree deal.

27 As reported in the Cincinnati Post, December 11, 1917. See also the Baltimore Sun, December 30, 1917.

28 Per an unidentified 1918 news article in the Lavender file at the Giamatti Research Center.

29 As reported in Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, April 3, 1918, Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, April 4, 1918, Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Press, April 7, 1918, and elsewhere.

30 As per the New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 18, 1918.

31 As per the Canton (Ohio) Repository, April 7, 1918, and Colorado Springs Gazette, April 11, 1918.

32 As reported in the Macon Telegraph, June 25 and 29, 1922.

33 As reported in the Columbus Daily Enquirer, July 30, 1922.

34 As per the New Orleans States, July 25, 1922, and the Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, July 29, 1922.

35 As per the Macon Telegraph, August 11, 1922.

36 An entry in Jimmy Lavender’s January 1960 death certificate indicates that he was the widower of Maggie Wooten, suggesting that Jimmy remarried sometime after Aline’s death. No further evidence of this possible second wife, however, was discovered by the writer.

37 As per the Wikipedia entry on author Vincent Starrett.

Full Name

James Sanford Lavender

Born

March 26, 1884 at Barnesville, GA (USA)

Died

January 12, 1960 at Cartersville, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.