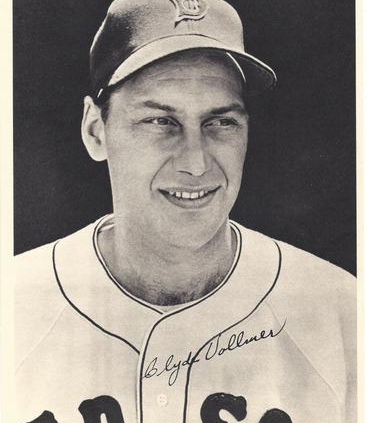

Clyde Vollmer

On May 31, 1942, the Cincinnati Reds prepared to host the Pittsburgh Pirates in a Memorial Day doubleheader. The previous two days had been disastrous for the Reds; a rash of injuries had decimated their outfield ranks. Ival Goodman was already nursing an injured ankle as the series began. On Friday, Hank Sauer, too, suffered an ankle injury that left him unavailable for the next afternoon’s game. During Saturday’s game three more outfielders went down: center fielder Mike McCormick broke his leg while sliding into second base, replacement center fielder Harry Craft suffered a concussion after an outfield collision with right fielder Gee Walker and was carried from the field on a stretcher, and Walker could not bat when his turn came up. Things had gotten so bad on the injury front that at one point the Reds took the field with catcher Dick West playing left field and pitcher Bucky Walters playing center.

On May 31, 1942, the Cincinnati Reds prepared to host the Pittsburgh Pirates in a Memorial Day doubleheader. The previous two days had been disastrous for the Reds; a rash of injuries had decimated their outfield ranks. Ival Goodman was already nursing an injured ankle as the series began. On Friday, Hank Sauer, too, suffered an ankle injury that left him unavailable for the next afternoon’s game. During Saturday’s game three more outfielders went down: center fielder Mike McCormick broke his leg while sliding into second base, replacement center fielder Harry Craft suffered a concussion after an outfield collision with right fielder Gee Walker and was carried from the field on a stretcher, and Walker could not bat when his turn came up. Things had gotten so bad on the injury front that at one point the Reds took the field with catcher Dick West playing left field and pitcher Bucky Walters playing center.

With few outfield options available to manager Bill McKechnie, Cincinnati GM Warren Giles contacted the Syracuse Chiefs, his club’s Double-A (top-level) minor-league affiliate, “begging for the best help available.”1 He asked manager Jewel Ens to “give us somebody who can play the field respectably.”2 That night, 20-year-old Clyde Vollmer boarded a 1:00 A.M. train for Cincinnati to join his hometown team in the major leagues.

Clyde Frederick Vollmer was a big youth. At 6 feet 1 inch tall and a solid 190 pounds, his teammates called him Big ’Un. Born in Bridgetown, a Cincinnati suburb, on September 24, 1921, Vollmer had first starred at age 14 in the Bridgetown Baseball League, where in 1935 he led his team to the Hamilton County Grade School championship. Later, he played American Legion ball as a member of Cincinnati’s Bentley Post. By the time he left Western Hills High School in 1938 (a school that would also produce, among others, Don Zimmer, Russ Nixon, Eddie Brinkman, and an infielder named Pete Rose), Vollmer had been well scouted by the Reds. The following year, 1939, Frank Lane, Cincinnati’s farm director, signed the 17-year-old to a Cincinnati contract for $75 a month.

Almost immediately Vollmer showed he was a legitimate major-league prospect. He began his professional career in 1939, in the Class-D Bi-State League, playing in the outfield for the Bassett (Virginia) Furniture Makers. In 77 games, he produced a .310 batting average, smashed six home runs, and slugged an impressive .461. Returning to Bassett in 1940, the big slugger was even better, as he played in 119 games and posted averages of .366 batting and .607 slugging, with 21 home runs and 45 doubles.

He also proved to be a fine defensive player. Indeed, it wasn’t his hitting that recommended Vollmer for promotion to Crosley Field; rather, it was for his fielding. While compiling a fine .970 fielding average at Bassett in 1940, Vollmer committed only seven errors and totaled 21 outfield assists. So impressed were the league’s sportswriters that Vollmer was the unanimous choice as right fielder on the Bi-State League All-Star team.

In 1941, Vollmer was promoted to the Columbia (South Carolina) Reds, in the Class-B South Atlantic League. While the big right-handed slugger had proved to be a consistent .300 hitter against Class-D pitching, he struggled in the faster Class-B ball. In 112 games, Vollmer batted just .248, although he again displayed good power, leading the league with 17 home runs while also stroking 22 doubles and 4 triples. During the September playoffs, Vollmer hit four home runs, two in one game, as Columbia defeated Macon, four games to two.

By the opening day of the 1942 season, Vollmer had once again earned a promotion: He was now the starting center fielder for the Syracuse Chiefs of the Double-A (later Triple-A) International League. Playing for manager Ens, Vollmer started slowly. After 32 games, he was batting just .214, with only one home run and a dismal slugging average of .325. Vollmer remained steady in the field. Just three years removed from Western Hills High, the young man from Cincinnati was wearing the uniform of his hometown team.

When Vollmer finally arrived at the Cincinnati Terminal that Sunday afternoon, the first game of the doubleheader was already under way. Hurriedly, he called home and told his father, Albert, a railroad worker, to get to the stadium, as Vollmer might see action in the second game. (In addition to Clyde, the third child and second son, Albert and his wife, Mabel, also produced Bernard, Myrtle, Melba, and Jewel.) Manager McKechnie started the rookie in left field in the second game, and Vollmer took his place in the Crosley Field outfield.

It took his father 2½ innings into that second game to get to the stadium. By chance, however, the Reds rookie left fielder had yet to come up for his first at-bat. Just as the public address announcer said, “The Cincinnati batter is Clyde Vollmer, left field,” Clyde’s father was settling into his seat. Several weeks later, manager McKechnie recalled for the press what happened next:

“He got to bat for the first time in the third inning,” related McKechnie. “Well, before he steps up he moves over to me and says, ‘Mr. McKechnie, I don’t know what the take sign is.’ And I say to him, ‘Young man, never mind the take sign. Just swing at the first pitch.’ Well, Max Butcher is the Pittsburgh pitcher, and Vollmer followed instructions perfectly … swung at the first pitch and knocked it on a line off the top of the laundry roof in left field.”3

Vollmer became one of only 24 major leaguers (through 2008) to hit a home run on the first pitch thrown to him in the major leagues.

It was an auspicious debut. Yet it was the lone highlight of a brief first stay in the major leagues. Over his next 33 at-bats, Vollmer struggled mightily, managing just two more hits. A week after his historic home run, McKechnie sent the young outfielder to the bench, telling the press, “He is a big boy with power and class in the field. Some day he will make me a fine outfielder. But I doubt that he is ready yet.”4 In fact, he wasn’t.

On June 21, after just three hits in 34 at-bats (.088), Vollmer was optioned to Birmingham. He wasted no time getting his hitting back on track. Perhaps more relaxed away from the glare of his hometown, Vollmer made an immediate impact. In his first game he belted a triple and two singles and made three spectacular catches in the outfield; by July, it was reported that “no less a baseball brain than Pie Traynor advises … Clyde Vollmer is the best-looking prospect in the Southern Association.”5 In August, when Birmingham split a doubleheader with the Atlanta Crackers, Vollmer’s two-run homer in the first game was “only the fifth home run ever hit into the left-field stand at Atlanta Park.”6 And by September, Vollmer had played in 83 games for the Barons, batted .309, and compiled a .462 slugging average. On September 6, when the Reds expanded their roster, Vollmer was recalled to Cincinnati. Yet he played in only two games, produced a single in six at-bats, and finished the season with the Reds with a .093 batting average and one historic home run in 12 games. It was more than three years before the Big ’Un had the chance to hit another.

When the Reds opened their 1943 spring training in Bloomington, Indiana, Vollmer was thousands of miles away and wearing a much different uniform: He had joined the Army on October 31, 1942. Vollmer remained in the Army for three years, until he was discharged in the fall of 1945.

By the following spring, Vollmer was ready to resume his career. As training got under way in Tampa, Florida, in February 1946, he was one of 52 players in the Reds’ camp. With their outfield situation unsettled, management was hopeful that Vollmer could win a starting position, and General Manager Giles was pleased with the slugger’s performance in spring training, so much so that he made a rather startling comparison.

“Not only do I believe Vollmer will be our regular left fielder,” Giles opined to the press in March, “but what’s more, I feel he may develop into another Joe DiMaggio. He has all the potentialities. He’s built along the same lines as DiMaggio. He uses the same stance at the plate as does the Yankee Clipper. He has the speed and throwing arm of a great outfielder. … You’ll hear a lot of Vollmer.”7

Whether or not Giles truly believed his own assessment or was simply trying to instill confidence in his young hometown player is unclear. Though he made the team, Vollmer’s stay was very brief: He saw action in only one game, striking out as a pinch-hitter on April 24, before the Reds determined he was still not ready and optioned him again to the minors. This time, though, they loaned him to another team, the Rochester Red Wings, the St. Louis Cardinals Triple-A International League affiliate. Vollmer played in 103 games and batted .275, while blasting nine home runs among 146 total bases (his slugging average was .432), before being recalled to the Reds on August 12. Over the remainder of the National League season, however, Vollmer played just eight games for Cincinnati, collected four hits in 21 at-bats, and wound up the season with a .182 average and one RBI. After two failed stints with the Reds, it appeared Vollmer’s chances with his hometown team were dwindling.

The 1947 campaign appeared last best chance. Playing for a new manager, Johnny Neun, who was determined to rebuild the Reds with youth, Vollmer finally spent the entire season on the Cincinnati roster. Vollmer once again failed to live up to his promise. After starting in center field on Opening Day and batting fourth, Vollmer was soon benched, and rarely played during the remainder of the season. In the end, he appeared in only 78 games, totaled just 155 at-bats, and finished the season with a paltry 34 hits and a .219 batting average. Moreover, his power all but disappeared, as Vollmer recorded an anemic slugging average of .303, hitting just one home run and driving in 13 runs. While he opened the 1948 season again on the Reds’ roster, he appeared in only seven more games, singled once in nine at-bats, and was finally released by the Reds to Syracuse on May 15, 1948. Almost six years to the day from when he had homered in his hometown on his first major-league pitch, Vollmer’s Cincinnati career had come to an end.

“That was my lowest point in baseball,” he later said. “The Reds were through with me. They sold me outright to Syracuse, and I figured I’d never get back into the big leagues.”8

This time in Syracuse, Vollmer turned his career around. Perhaps he had his new wife to thank for inspiration. After the 1947 season, Vollmer had married Margaret Oberberg, and it proved to be a wonderful, 59-year union that produced one daughter, Claudia. More likely, however, Vollmer’s modest success after his Cincinnati release had more to do with getting out from under the pressure of playing before family and friends. Warren Giles said in 1951, when asked why he had let Vollmer go: “He couldn’t make good for us. Don’t forget, he was a Cincinnati boy, and to me it looked like the old story of the hometown boy trying too hard to make good and suffering because of it.”9

For whatever reason, though, in Syracuse, Vollmer finally gave an explosive performance and posted the kind of numbers Giles had always predicted. In 122 games, the 27-year-old hit 32 home runs and drove in 104 runs, had 255 total bases for a slugging average of .580, and finished with 127 hits and a .289 batting average. Vollmer proved he could be a productive player and it didn’t take long before he was in the major leagues once again. On September 26, while the Chiefs were in Montreal, Vollmer learned that he had been traded to the Washington Senators (for outfielder Carden Gillenwater – as well as, according to some reports, Sammy Meeks and $25,000 cash), so he packed his bags and headed to the American League.

Switching leagues proved to be just the change Vollmer needed. About his trade to Washington, the slugger later related, “I was glad to get away from the National [League]. All I remembered over there was failures with the Reds.”10 He arrived in Washington in time to play one game that season, starting in center field on October 2 and collecting two singles in five at-bats, and then headed home to prepare for 1949.

The ‘49 season was a study in contrasts. On the one hand, Vollmer gained the distinction of hitting at least one home run in every stadium in the league; on the other, he never made much of an impression on Senators management. Vollmer said in 1950, a year after he had been traded away from the Senators, that Washington manager Joe Kuhel “didn’t even know my name. That’s a fact. I had been with the Nats all season and it was late in August when Kuhel started to introduce me to someone. He got the first name all right, but spluttered around with my second until he finally came out with ‘Milan – Clyde Milan.’ Milan, of course, was a coach with us.”11

It was symbolic of Vollmer’s 1949 season in Washington. Platooned for most of the first month, he was then used mainly as the starting center fielder, but ultimately failed to impress as a consistent run producer. Playing in 129 games, Vollmer batted .253 with 14 home runs and 59 runs batted in, producing a slugging percentage of just .391. By the time the 1950 season opened, Vollmer was deemed expendable, and on May 7, after playing in just six games for the Senators, he was traded to the Boston Red Sox for outfielder Tom O’Brien and infielder Merrill Combs.

Vollmer was pleased with the trade. “Getting a chance to hit in Fenway Park was wonderful,” he said a year later. Washington’s Griffith Stadium “is really big. I knew a lot of the balls I was hitting there would reach that Boston fence.”12 For the next season and a half they did, and the Big ’Un hit home runs far more frequently than before.

If Vollmer was expected to play every couple of days and add occasional power to the Boston lineup, circumstances soon dictated a larger role for the 28-year-old. First, Vollmer realized a singular achievement. On June 8 at Fenway Park, the Red Sox annihilated the St. Louis Browns, 29-4, and the outfielder, batting leadoff, became the only player in history to come to the plate eight times in eight innings (he finished 1-for-7, walking once and hitting a double). Then, on July 11, in the All-Star Game in Chicago, Ted Williams fractured his elbow. When the Sox resumed their season after the All-Star break, manager Steve O’Neill played Vollmer in Williams’ spot, starting him in left and batting him third. “He’s a good outfielder, pretty good hitter and fast,” O’Neill said. “He gets away from the plate faster than Vern] Stephens or Walt] Dropo and he’s less likely to be doubled up. I’d thought of moving and Dropo up in the order, but this may work out better.”13

In his first game starting in place of Williams, on July 13 at Fenway Park, Vollmer hit a home run and two doubles in an 8-7 victory over the White Sox. In the 32 games in which he filled in, he batted a respectable .281, with three home runs and 22 RBIs. Returning to a part-time role after Williams returned, Vollmer then provided even grander heroics when, as a pinch-hitter, he blasted his first-ever grand slam, at Fenway Park against Cleveland on August 27. The blast propelled the Red Sox to an 11-9 victory. In all, Vollmer appeared in 57 games after the trade from Washington, batted a major-league career-best .284, and hit seven home runs, drove in 37 runs and posted a slugging mark of .467. Acquired to add depth to the Boston outfield, Vollmer helped keep the Red Sox in contention in 1950 with his clutch hitting.

And then came 1951 and one of those inexplicable streaks that power hitters sometimes experience. When it was over he deemed his performance “the greatest satisfaction I’ve ever got out of baseball.”14

Before the Fourth of July, Vollmer got his season off to a good start, but not one that suggested fireworks. As Boston’s fourth outfielder, Vollmer played in 33 games, batted 73 times, posted a .260 average, and hit four home runs. On July 4, at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, in the first game of a doubleheader, he hit a solo home run, and over the next 23 days he had one of the most impressive streaks in baseball history.

Consider this performance: July 6 — a two-run triple in a 6-2 win over New York; July 7 – a grand slam in the first inning of a 10-4 win over New York; July 8 — a two-run homer that gave Boston a 4-3 lead in an eventual 6-3 win over New York; July 12 — a two-run homer in the first game of a doubleheader against Chicago, won by Boston, 3-2; in the second game drove in the winning run with a sacrifice fly in a 6-5 win; July 13 — a homer in the fifth inning and an RBI single in the 19th in a 5-4 loss to Chicago; July 14 – a two-run single in the ninth that defeated Chicago, 3-2; July 18 — a solo home run for the first Boston run in a 4-3 win over Cleveland; July 19 — two home runs in a 5-4 loss to Cleveland; July 21 – a home run, double, and single, with four RBIs, in a 6-3 win over Detroit; July 26 – three home runs driving in six runs in a 13-10 win over Chicago; July 28 — singled in the 15th inning to tie the score, 3-3, against Cleveland, and hit a grand slam in the 16th to give Boston an 8-4 victory.

It was an amazing run. In 24 games from July 4 through July 28, Vollmer collected 30 hits in 98 at-bats (.306); totaled 13 home runs and 38 RBIs; and smashed 74 total bases for a .755 slugging average. His 13 home runs contributed to 12 Boston victories, and his three-home-run game on July 26 made Vollmer only the fourth hitter in history to hit that many in one game at Fenway Park.

He had been an unlikely hero. Indeed, asked during the streak to explain his performance, Vollmer told the press, “A hero today, a forgotten man tomorrow. … I can’t honestly explain what has been happening. I’m swinging the same bat in the same groove. Nothing is different. I just hit a hot streak.”15

Vollmer was reticent when interviewed. “I don’t know what they want me to say,” he explained. “Nobody ever tried to make a hero out of me before. Newspaper guys never bothered me much until now. I don’t mean that they bothered me. I mean they never paid me any attention, or asked me any question. I’ll say one thing, however,” he concluded. “It’s more fun when you’re hitting home runs.”16

It also put money in Vollmer’s pocket. At the start of the season, he was the lowest-paid player on the Boston roster, at a salary of $7,500. At midseason, however, it was reported that Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey had rewarded Vollmer for his performance by raising his salary to $12,500.

Through it all, the sudden notoriety seemed to have little effect on Vollmer’s disposition; he remained a quiet and reserved player. That came as no surprise to Ruth Hatch. A 50-ish widow, Mrs. Hatch ran a rooming house on Bay State Road, close to Fenway Park, where Vollmer roomed with half a dozen other Red Sox players. (Clyde’s wife and daughter were back home in Ohio.) The men were the “town’s heroes,” and Mrs. Hatch shielded the players from local “bobby-soxers.” She was sure that Vollmer would stay grounded. “Clyde won’t get any swelled head like some of the others did,” she said.17 And Clyde never did.

The 1951 season was the pinnacle of Vollmer’s career. After posting a .251 average in 1951, scoring a career-high 66 runs, and compiling 22 home runs, 85 RBIs, and a .456 slugging average in 115 games, Vollmer returned to Boston in 1952 and, again in a reserve role, posted solid numbers: a .264 batting average in 90 games, with 11 home runs, 50 RBIs, and a .476 slugging average. That was his final full season with Boston. In 1953, after making one appearance for the Red Sox (he walked as a pinch-hitter), on April 22 he was sold back to the Senators in a cash transaction somewhere around the waiver price of $10,000. The deal brought Vollmer back to Washington to provide help with the Senators’ depleted outfield. He played in 118 games and batted .260 with 11 home runs and 74 batted in, and then played one final season in Washington, appearing in only 62 games (.256, two home runs). On September 17, 1954, the 32-year-old Vollmer asked for and was granted his unconditional release. In 10 major-league seasons, he had compiled a .256 batting average with 69 home runs, 40 of which came while he played in a Red Sox uniform.

Still, Vollmer wasn’t done. Over the next two seasons, he bounced around with three minor-league clubs, playing in Charleston (American Association) and Buffalo (International League) in 1955, and Buffalo and Little Rock/Montgomery (Southern Association; the franchise moved during the season) in 1956. And then, at the age of 35, he left the game for good.

Vollmer lived a full life after baseball. For more than 20 years, he owned the Lark Lounge in Florence, Kentucky, across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, and was a member of the American Legion, the Fraternal Order of Eagles/Cheviot Aerie, and the Delhi Senior Citizens. He died on October 2, 2006, in Florence. He was survived by his wife, Maggie; daughter, Claudia; and a brother.

Sources

Alton Evening Telegraph (Ohio), Baseball Digest, Blytheville Courier News (Arkansas),

Boston Post, Connellsville Daily Courier (Ohio), Charleston Daily Mail (West Virginia),

Charleston Gazette (West Virginia), Coshocton Tribune (Ohio), Dunkirk Evening Observer (New York), Lima News (Ohio), Mansfield News Journal (Ohio), Marion Star (Ohio), Middlesboro Daily News (Kentucky), Piqua Daily Call (Ohio), Portsmouth Times (Ohio),

The Sporting News, Syracuse Post-Standard, Syracuse Herald Journal, Van Wert Times-Bulletin (Ohio), Washington Post, Van Wert Times (Ohio), and Zanesville Times Recorder (Ohio)

Notes

1 Russ Needham, “A Dream Comes True Values Change Quickly,” Columbus Dispatch, June 4, 1942: 4-B.

2 Sy Burick, “Vollmer, the Enbalmer,” Baseball Digest, September 1951: 79.

3 The Old Scout, “Reds Continue Seeking Picket,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, June 13, 1942: 12.

4 The Old Scout.

5 Sid Feder, “Weinstock is Aspiring for Kessler Team,” Wilkes-Barre Leader, July 18, 1942: 11.

6 United Press, “Travelers Keeping Up Pace Against Vols in Drive for S.A. Flag,” Knoxville New-Sentinel, August 26, 1942: 9.

7 “Reds Meet Detroit Tigers in Exhibition Game Today,” Zanesville (Ohio) Signal, March 15, 1946: 13.

8 Bob Ajemian, “Vollmer Fires Bosox Victory Rockets,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1951: 3.

9 Shirley Povich, “All Vollmer Can Say: ‘It’s Fun to Hit Homers’,” Washington Post, July 29, 1951: C1.

10 Ajemian.

11 Gerry Moore, “Vollmer’s Grand Slam on Al Benton’s Curve First He Has Ever Hit,” unidentified newspaper clipping, August 1950, in Vollmer’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

12 Ajemian.

13 Ajemian.

14 Ajemian.

15 Jim Wood, “Big Clyde hits popularity streak,” Statesville (North Carolina) Daily Record, July 27, 1951: 14.

16 Wirt Gammon, “Just Between Us: Quotable Quotes,” Chattanooga Daily Times, July 31, 1951: 11.

17 “Vollmer ‘Reveals’ Recipe – ‘Meeting the Ball’ Better,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1951: 12.

Full Name

Clyde Frederick Vollmer

Born

September 24, 1921 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

October 2, 2006 at Florence, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.