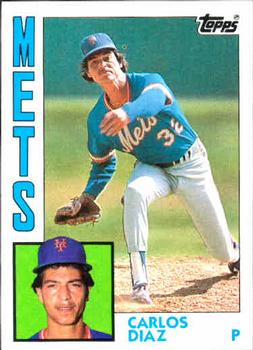

Carlos Diaz

Just five lefty pitchers born and raised in Hawaii have made it to the majors.1 Carlos Diaz was the third. In December 1983, coming off his best season, the wiry reliever was part of a unique trade involving Hawaiian lefty #4, Sid Fernandez. That deal paid off for the New York Mets. Fernandez was a key contributor to the World Series champions of 1986; he won a total of 98 games for the Mets and 114 in his big-league career. Diaz had one more good year (1985), but arm problems ended his time in baseball after spring training 1987.

Just five lefty pitchers born and raised in Hawaii have made it to the majors.1 Carlos Diaz was the third. In December 1983, coming off his best season, the wiry reliever was part of a unique trade involving Hawaiian lefty #4, Sid Fernandez. That deal paid off for the New York Mets. Fernandez was a key contributor to the World Series champions of 1986; he won a total of 98 games for the Mets and 114 in his big-league career. Diaz had one more good year (1985), but arm problems ended his time in baseball after spring training 1987.

Diaz’s Hispanic name led many to guess that he was from Latin America. In fact, his father – Carlos Antonio Diaz Sr. – was born in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico. His mother, Cecilia (née Rodrigues) was a 100% Puerto Rican from Hawaii. Both Carlos and Cecilia were proud members of the United Puerto Rican Association of Hawaii.2

Hawaii’s Puerto Rican community is not that numerous.3 Yet it has made a visible mark on the local culture in music, dance, and other areas – including baseball. At least two other Hawaiian big-leaguers – John Matias and his nephew Joe DeSa – had boricua heritage. All four of Matias’s grandparents came to Hawaii from Puerto Rico in the early 20th century, when many sugar cane workers sought new homes in the wake of natural disaster. The same was true of the parents of Cecilia Rodrigues, who was born in Wailuku on the island of Maui. In Puerto Rico, her family’s name had been spelled the Spanish way, with a ‘z’ on the end. It was changed to the Portuguese spelling in Hawaii, though – that community arrived there earlier and in greater numbers.4

Carlos Diaz Sr. (born 1929) was an Army veteran, and it was his military service that brought him to Hawaii. After retiring from the Army, the elder Diaz worked for Kodak Hawaii.5 He later became a warehouse manager for Executive Chef, a Honolulu kitchenware retailer that catered to commercial chefs.6 Cecilia founded a business called Mama Diaz Pasteles.7 Pasteles are a savory Latin American dish, very similar to tamales, that came to Hawaii via Puerto Rico.

Cecilia had six children from her previous marriage to a man named Hesia: Richard, John, Dennis, Frank, Marie, and Emelia. With Carlos Diaz Sr., she had five more: Carlos, Delbert, Richard, Darryl, and Lori. In addition, there were two hanai sons, Enrique Rodrigues and Joel Daniels.8 Hanai is a Hawaiian word that means informal adoption, though it has deeper significance in the local culture. “We were all one,” said Carlos’s sister Emelia of the large blended family. Spanish was spoken in the household, but only between the parents and grandparents. “The kids could understand it but did not speak it,” Emelia noted.9

Hawaiian statehood was still over a year away when Carlos Diaz Jr. was born on January 7, 1958.10 When he was just a few months old, he got a nickname from his father: “Bimbo,” from a clown by that name. It was a term of endearment because baby Carlos “had the bluest eyes then and was chubby with no hair,” Emelia remembered. “And later he was a little mischievous. He wore that nickname proudly until the day he died.”11

Carlos Jr. was born and grew up in Kaneohe, on the windward side of Oahu, across the Kaneohe Peninsula from the urban center of Honolulu.12 The neighborhood is notable for its high proportion of residents who are active in the military.

Young Carlos was nine years old in 1967, when Mike Lum became the first major-leaguer born and raised in Hawaii since Hank Oana during World War II. He played in Little League from ages nine to 12, then moved up to Pony League for ages 12 to 14. After that, he got invited to play in other leagues, including the AJA League for Americans of Japanese Ancestry – even though he had no such ethnicity. “He was in a baseball uniform more than he was in street clothes,” Emelia recalled. “He was always ready to play, on time or earlier. He was always conservative, quiet and reserved.”13

Diaz went to James B. Castle High School in Kaneohe. There he played basketball as well as baseball. According to one of his teammates at Castle, a man named Lance Terayama, Diaz posted a perfect ERA of 0.00 during his senior year, 1976.14 The Knights finished in fourth place in Hawaii’s state baseball tournament that year. The champion was Aiea High School, led by pitcher Derek Tatsuno, who went on to a phenomenal career at the University of Hawaii, but never fulfilled his promise as a pro.

Diaz was not drafted out of high school. He did not go to college straight away, either; instead, he played in the AJA League and others. Thanks to coaches’ connections, however, he went to Allan Hancock Junior College in Santa Maria, California.15 He pitched two years for the Bulldogs, a team that has sent three other men to the majors: Ted Davidson, Brian Asselstine, and Bryn Smith.

In the third round of the January 1979 draft, the Seattle Mariners selected Diaz, but he decided not to sign at that time. The M’s were persistent, though, and made Diaz their #1 choice in the secondary draft that June. That offer he accepted.

Except for his time in winter ball, Diaz did not start a single game during his entire pro career. This may have reflected views about his durability, considering his slender build (6 feet even and 170 pounds). In 1983, Diaz said, “I like the bullpen, but I would like to start at least one game soon just to see what I could do.”16 His longest stint in the majors was five innings (on October 1, 1985).

During his first pro season in 1979, he pitched in 28 games: two for Bellingham in the Northwest League and 26 for San José in the California League. He posted overall stats of 4-1 with a 4.78 ERA and five saves.

On October 20, 1979, Diaz married Barbara Souza. She was from Lompoc, California, about half an hour south of Santa Maria in Santa Barbara County. The couple had three children: daughters Kari Ann and Erica and son Cory. They were divorced around 1990.17

Soon after his marriage, Diaz went to play ball in Puerto Rico. There, thanks to his parentage, he counted as a “native” player rather than an import for roster purposes. He spent the winter of 1979-80 and four of the following five with the Santurce Cangrejeros. The only starts of Diaz’s pro career came in this league.18

The numbers from his first pro season were not imposing, yet Diaz jumped past Class AA in 1980, going to Triple-A Spokane. That team was in the Pacific Coast League, which then included the Hawaii Islanders. Thus, Diaz had opportunities to pitch in front of a hometown crowd. “[Diaz] had about 80 family and friends in the gathering of 815 in Aloha Stadium May 8 to see him try to thwart the Islanders’ attack. After disappointing them with below-average efforts his first three outings in Hawaii, Diaz tossed hitless ball for 3 2/3 innings to help the Indians post a 6-5 victory in 11 innings.”19

In March 1981, the Atlanta Braves obtained Diaz in the trade that sent outfielder Jeff Burroughs to Seattle. Viewed out of context, the transaction looks surprising because no other players were involved. Diaz had posted a record of 3-5, 3.94 with nine saves in 58 games for Spokane. He had yet to pitch in the majors. Although Burroughs – the former AL MVP – was coming off two subpar seasons, he was still an established big-league slugger.

However, there were unusual circumstances – Burroughs was disgruntled with his situation in Atlanta. Also, the Braves had made a loan of $400,000 to him that was still unpaid, which led to a contract impasse. The Mariners took over the whole of Burroughs’ contract, and the loan was transferred to a Seattle bank.20 Burroughs had actually agreed to the deal in December 1980; Diaz was the proverbial “player to be named later” while the details were ironed out.21

Diaz spent the 1981 season with Atlanta’s Triple-A farm team, Richmond. He put up good numbers out of the bullpen: 3-3, 2.81 with 11 saves in 35 games. He also started the ’82 season at Richmond and continued to perform well (3-4, 2.70 with nine saves in 31 games).

On June 30, 1982, the Braves traded lefty Larry McWilliams – who had been pitching mainly in relief that season – to the Pittsburgh Pirates. They received Pascual Pérez in return and assigned the Dominican to Richmond. Meanwhile, Atlanta manager Joe Torre moved Rick Camp from the bullpen into the starting rotation.22

The big club also called up Diaz. He made his debut at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium the very same night, entering in relief of Phil Niekro in the ninth inning. He allowed a run, which left the Braves down 4-1. However, Atlanta rallied for four in the bottom of the ninth, so the brand-new rookie got the win.

Ten days later, in his third appearance, Diaz got another win. He got the first of his four major-league saves on July 29 against the San Diego Padres. He pitched in 19 games that summer with Atlanta, going 3-2 with a 4.62 ERA. He also earned another nickname: “The Mad Hawaiian.”23 Apparently he had picked up some of Al “The Mad Hungarian” Hrabosky’s mannerisms on the mound.24

The Braves were fighting for the NL West division title with the Los Angeles Dodgers. However, a team that was in rebuilding mode had its eye on the reliever – the Mets traded for Diaz on September 10. The New York Times reported that Atlanta had been seeking veteran righty Tom Hausman for six weeks. Frank Cashen, general manager of the Mets, said, “We almost had a deal for Diaz in the middle of the season, but it didn’t work out.’”25

Joe Torre, who had managed Hausman with the Mets before taking over as Braves skipper in 1982, said, “At this time of year I’m looking for experience.”26 Hausman said, “I’m going to pitch a lot, and that’s the only thing that matters to me.”27 Yet he wound up in only three games with Atlanta down the stretch. He was not on the roster for the NL Championship Series and never appeared again in the majors.

Cashen added, “We are happy to be getting a younger player, and the Braves were reluctant to trade a pitcher as young as Diaz. The deal would not have happened were the Braves not in the middle of a pennant race.”28

Diaz got into four games as a Met in 1982 and then went back to play in Puerto Rico. Ahead of the 1983 season, The Scouting Report annual said that he tried to overpower batters, and that he needed experience and better control to succeed. One of the contributors to the book, longtime Mets broadcaster Ralph Kiner, said, “Carlos needs to show considerable improvement to stay on a major league roster.” Tim McCarver, who joined Kiner in the Mets broadcast booth in 1983, was more optimistic, saying, “He could develop into a good reliever.” 29

They were both right. At the end of spring training 1983, New York sent pitchers Brent Gaff, Tom Gorman, and Terry Leach down to Triple-A Tidewater. Doug Sisk, who had broken in with the Mets the previous September, and Diaz survived the competition.30 They formed a highly effective bullpen trio with future playoff and World Series hero Jesse Orosco. Used mainly in long and middle relief, Diaz went 3-1, 2.05 and picked up two saves in a career-high 54 games. He allowed just one home run in 83 1/3 innings pitched.

The first of Diaz’s saves, on August 6 at Chicago’s Wrigley Field, came in a true “fireman” situation. Starter Walt Terrell – who drove in all four of the Mets’ runs that day with two homers off Ferguson Jenkins31 – took a shutout into the eighth inning but tired. He allowed one run and had runners on first and third with one out when manager Frank Howard called for Diaz. The reliever walked Bill Buckner to load the bases, but then struck out the dangerous Ron Cey and Leon Durham to end the threat. In the ninth, he set the Cubs down in order.

The Scouting Report had spoken well of Diaz’s repertoire. “He throws a better than average fastball and usually manages to keep it down. His curve has good rotation, and he also throws a fairly good slider.”32 However, that book went to print before Diaz added a new weapon: the spitball.

“You know the pitch,” wrote Mike McAlary of the New York Post, six days after Diaz’s save at Wrigley. “It’s the same type Gaylord Perry built his soggy reputation on. . . In the spring, no one gave Diaz a chance of doing any job for the Mets. He was No. 15 on a team needing just 10 pitchers. . . However, Diaz worked closely with George Bamberger [who had managed the Mets until resigning on June 3] and learned his Staten Island Sinker. . . ‘It’s what I call a situation pitch,’ [said Diaz]. ‘If I get the right situation, I throw it.’”33 Bamberger – a former pitcher and pitching coach – had taught others the spitter. A leading example was Mike Caldwell, who turned around his flagging career in 1978 when Bamberger became manager of the Milwaukee Brewers.

Although the 1983 Mets still finished last in the NL East, discerning fans could tell that the club was on the rise. A huge factor was Frank Cashen’s canny trades, many for pitching. That winter, the Mets got peak value for Diaz when they sent him to the Dodgers in the four-player trade that brought the young Sid Fernandez. The Mets also sent all-purpose player Bob Bailor to L.A. while getting infielder Ross Jones.

Bill Conlin of The Sporting News had an intriguing comment after the deal: “You can find more big league scouts who are high on lefthanded reliever Carlos Diaz than on former Dodger strikeout phenom Sid Fernandez.” Conlin also said that Cashen was “rolling the dice” and that Dodgers general manager Al Campanis seldom made mistakes with young players. 34 Campanis later admitted, though, that letting Fernandez get away was one of them.35

In fairness, Los Angeles was very deep in starters; that rotation included three established lefties (Fernando Valenzuela, Jerry Reuss, and Rick Honeycutt). There was a hole in the bullpen, though, because of lefty closer Steve Howe’s cocaine problems. Dodgers manager Tom Lasorda said, “Howe was the reason it [the trade] occurred.”36 Also, Los Angeles had traded lefty John Franco – then a prospect, later an effective closer for many years – to the Cincinnati Reds that May.

Joseph Durso of the New York Times further illustrated each club’s thinking. Whereas the Mets were still looking to the future, Los Angeles “acquired two professionals who could help them win now.”37 As he had done when obtaining Diaz in 1982, Cashen turned this desire to his advantage.

Another of the few feature articles about Diaz appeared in May 1984 in the South Bay Daily Breeze (a newspaper serving the South Bay region of Los Angeles County). The main focus was his quiet life at home with Barbara and 15-month-old Kari Ann. After living only in apartments previously, the family had found a house of their own in the San Fernando Valley, near Dodger Stadium. Diaz said that he liked California a lot and saw many similarities between it and Hawaii. He also talked about his new favorite leisure sport – fishing. Bob Bailor, an avid outdoorsman, got Diaz into it during spring training in Vero Beach.38

That article noted that with Howe suspended for the year, the Dodgers were still counting on Diaz as the left-handed “stopper” out of their bullpen in 1984. (Back then, many teams used co-closers, one lefty and one righty.) However, Lasorda wound up entrusting most of the late-inning duties to burly right-handers Tom Niedenfuer and Ken Howell. Used largely as a situational reliever, Diaz had a disappointing year (1-0, 5.49 with just one save in 37 games). After a very rough outing on June 30 (seven earned runs in one inning), the Dodgers sent him down to Triple-A Albuquerque for several weeks.

Diaz had not played in Puerto Rico during the 1983-84 season, but he went back to Santurce for the winter of 1984-85. In his final season with the Crabbers, he was 4-0, 4.43 in 42 2/3 innings. That brought his career totals there to 13-5, 3.98 in 185 2/3 innings.

Back with Los Angeles in 1985, he rebounded nicely. He was 6-3, 2.61 in 46 games – and spent the entire season with the big club. The Dodgers won the NL West, and Diaz got into Games Three and Four of the playoff series against the Cardinals. He pitched three innings and gave up a run on five hits.

Diaz got into just 19 games for the Dodgers in 1986 from April through late July. He recorded no decisions and a 4.26 ERA in 25 1/3 innings pitched. He spent part of May on the disabled list with a sore shoulder and was with Albuquerque again for a couple of stretches (1-4, 5.64 in 14 games). He was recalled in September but didn’t appear in any games. Los Angeles released him that October.39

In December 1986, Diaz signed as a free agent with the Oakland A’s. Oakland released him in March 1987, and at age 29, he decided not to continue in the minors. He returned to Hawaii, taking a job with Pacific Courier as a driver. He was eventually promoted to senior driver. Lance Terayama said, “He set the example for the young couriers. He was very dependable, working the early shift and starting at 3 a.m.”40

Diaz stayed involved with baseball. He was asked to play in local leagues, and in September 1989, he became pitching coach at Hawaii Pacific College (which became Hawaii Pacific University the following year).41 According to Bill Powers, Sports Information Director at HPU, “Publications at the time did not list the program’s assistant coaches. The baseball team did not have any full-time coaches at that time – the head coach was the only full-time employee.”42 Diaz’s sister Emelia supports Powers’ belief that Carlos was with HPC for probably just a season. He helped as a volunteer.43

The Hawaii Winter League – which featured top talent from the U.S. and Japan – operated from 1993 through 1997 and again from 2006 through 2008. To his family’s knowledge, however, Diaz was not associated with this circuit, likely because his job prevented it.

In spring 2001, Diaz was pitching coach at St. Louis School in Honolulu. Again this was probably for just one season, on a volunteer basis.44 Yet in his brief time at St. Louis, he helped develop a future big-leaguer, pitcher Brandon League. Diaz said, “He has awesome potential. He was doing great before I got here, so I hope I don’t mess him up.”45 Diaz helped League put more bite on his curveball and had him tinkering with a split-finger fastball.46 The righty was drafted in June 2001 and went on to an 11-year career in the majors (2004-14).

On December 30, 2004, Diaz got married for the second time, to Tracy Iwamoto.47 According to her, Carlos “didn’t talk much about his time in baseball, but every now and then a friend and former teammate like Bob Welch would visit.” She added, “He’d still follow the game, especially the World Series. He coached some summer leagues, Little League and stuff like that. And we’re season ticket holders for UH [University of Hawaii] baseball.”48

Carlos Diaz died on September 28, 2015. He was 58 years old. According to his family, the cause was a heart attack.49 He had been living in Kailua, a neighborhood adjoining Kaneohe to the east. Tracy and he did not have any children of their own, but Carlos was stepfather to Bryce, Vic, and Megen Miyahira, her children from a prior marriage.

Diaz was laid to rest in Hawaiian Memorial Park in his birthplace, Kaneohe. On the Life Tributes page that was set up on the mortuary’s website for Diaz, a high-school classmate named Lynette Santos wrote, “Bimbo was a friend to all. He had a gift of making you feel like he’d known you all his life. He always took the time to talk and he’d remember stories from small kid time that always made me laugh that he remembered. Bimbo never boasted of his many accomplishments, rather wanted to know how I was and the family. He always spoke on a personal level, which made him such a sweet man. He was truly a godsend for everyone he met.”50

Acknowledgments

Mahalo to Emelia Rodrigues, sister of Carlos Diaz, for her help with this story (telephone interview, January 31, 2017). Continued thanks to SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado, official historian of the Puerto Rican Winter League, for providing Diaz’s statistics there.

Additional Sources

comc.com (online trading card database)

Notes

1 The others (as of 2017): Doug Capilla, Fred Kuhaulua, and Onan Masaoka. Capilla moved from Hawaii to California when he was 16 years old, after his sophomore year in high school. See Earl Lawson, “Capilla Tags All the Bags on Cincy Joyride,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1977, 50. One more southpaw, Steve Cooke, was born in Hawaii but moved to Oregon as a child. See Lou DiPietro, “Kirby Yates driven by both his Hawaiian and family baseball heritages,” YESNetwork.com, March 6, 2016.

2 “Carlos Antonio Diaz Diaz,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, February 28, 2013. The Hispanic tradition of double surnames shows that both this man’s parents bore the family name Díaz. “Cecilia R. Hesia Diaz,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, November 12, 2012.

3 It numbered just 4,289 as of 1960 and about 44,000 as of 2010. Clara E. Rodriguez, Puerto Ricans: Immigrants and Migrants, Bethesda, Maryland: People of America Foundation, 1991: 9. “2010 Census Shows Nation’s Hispanic Population Grew Four Times Faster Than Total U.S. Population,” U.S. Census Bureau press release, May 26, 2011. Pavel Stankov, “Hawaii’s Latinos Defy Stereotypes,” Hawaii Business, May 2013.

4 Telephone interview, Emelia Rodrigues with Rory Costello, January 31, 2017 (hereafter “Rodrigues interview”). “Cecilia R. Hesia Diaz”.

5 Rodrigues interview.

6 “Carlos Antonio Diaz Diaz”

7 “Cecilia R. Hesia Diaz”

8 “Carlos Antonio Diaz Diaz”. Rodrigues interview.

9 Rodrigues interview.

10 Joe DeSa was the last big-leaguer to be born in Hawaii while it was still a territory. His birthdate, July 27, 1959, came just 25 days before The Aloha State entered the Union.

11 Rodrigues interview.

12 The City and County of Honolulu covers the entire island of Oahu.

13 Rodrigues interview.

14 Dave Reardon, “Former Castle standout played 5 seasons in big leagues,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, October 18, 2015.

15 Rodrigues interview.

16 Mike McAlary, “Diaz’ ‘Forkball’ Paying Dividends for Mets,” The New York Post, August 12, 1983.

17 Terry Johnson, “At Home with…Carlos Diaz and Family,” South Bay Daily Breeze (Torrance, California), May 15, 1984, 8-9. Wedding date comes from a 1984 baseball card, part of a Dodgers set with an anti-drug message issued by the Los Angeles Police Department. Barbara’s maiden name and the date of the divorce come from the Rodrigues interview.

18 Thomas E. Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999: 142, 231.

19 “Pacific Coast League,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1980, 39.

20 “Braves Trade Burroughs to Mariners for Reliever,” The New York Times, March 8, 1981.

21 “Burroughs agrees to deal,” United Press International, December 12, 1980.

22 Tim Tucker, “Wigwam Wisps,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1982, 28.

23 Steve Wulf, “Not Home Free Yet,” Sports Illustrated, August 9, 1982.

24 Marybeth Sullivan, editor, The Scouting Report, 1983, New York, HarperCollins: 1983, 534.

25 James Tuite, “Mets Obtain Braves’ Reliever,” The New York Times, September 11, 1982.

26 Walt Smith, “Braves Deliver for Perez,” United Press International, September 11, 1982.

27 James Tuite, “Mets Set Back Cardinals, 2-1,” The New York Times, September 11, 1982. This version of Tuite’s article, with some different content, probably appeared in a different edition.

28 Ibid.

29 The Scouting Report, 1983, 534.

30 Joseph Durso, “Seaver Passes Test on Thigh and May Start Opener,” The New York Times, April 3, 1983.

31 It took nearly 33 years until another Mets pitcher went deep twice in a game. Noah Syndergaard did it on May 11, 2016.

32The Scouting Report, 1983, 534.

33 McAlary, “Diaz’ ‘Forkball’ Paying Dividends for Mets”

34 Bill Conlin, “Designated-Hitter Rule Suffers Major Defeats on Four Fronts,” The Sporting News, December 26, 1983, 49.

35 Murray Chass, “Fernandez No. 1 on the List Of Dodgers Who Got Away,” The New York Times, May 18, 1986.

36 Ibid.

37 Joseph Durso, “Brisker Trading Is Foreseen,” The New York Times, December 11, 1983.

38 Johnson, “At Home with…Carlos Diaz and Family”

39 “Dodgers Raise Prices, Release Carlos Diaz,” Los Angeles Times, October 18, 1986.

40 Reardon, “Former Castle standout played 5 seasons in big leagues”

41 “Carlos Diaz, Former Major League Reliever, HPC’s New Pitching Coach,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 20, 1989, D1.

42 E-mail from Bill Powers to Rory Costello, January 10, 2017.

43 Rodrigues interview.

44 Rodrigues interview.

45 Kyle Sakamoto, “St. Louis’ League, Kam’s Sardinha friendly ILH rivals,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 14, 2001.

46 Jason Kanehiro, “It’s not easy to hit against this ‘League,’” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 15, 2001.

47 Rodrigues interview.

48 Reardon, “Former Castle standout played 5 seasons in big leagues”

49 Ibid.

50 “Carlos ‘Bimbo’ Antonio Diaz Jr.,” (http://www.hawaiianmemorialparkmortuary.com/obituaries/Carlos-Bimbo-Diaz/)

Full Name

Carlos Antonio Diaz

Born

January 7, 1958 at Kaneohe, HI (USA)

Died

September 28, 2015 at Kaneohe, HI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.