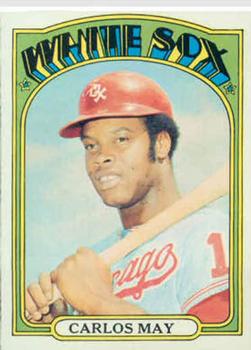

Carlos May

Carlos May was called “Tank” for his burly stature. At 5-feet-11 and 200 pounds, he had the physique of someone who carried a pigskin on a football field. However, May was also a talented baseball player, adept at hitting the horsehide. He reached the big leagues in 1968 at the age of 20. His career was taking off and one year later he appeared in the 1969 All-Star Game. But just a few weeks thereafter, while he was away from the White Sox fulfilling his military service obligation, May suffered a career-threatening injury, losing part of his right thumb during a gunnery exercise.

Carlos May was called “Tank” for his burly stature. At 5-feet-11 and 200 pounds, he had the physique of someone who carried a pigskin on a football field. However, May was also a talented baseball player, adept at hitting the horsehide. He reached the big leagues in 1968 at the age of 20. His career was taking off and one year later he appeared in the 1969 All-Star Game. But just a few weeks thereafter, while he was away from the White Sox fulfilling his military service obligation, May suffered a career-threatening injury, losing part of his right thumb during a gunnery exercise.

Nonetheless, he persevered, rehabilitated, and went on to have a strong career that lasted through 1977 in the majors plus four more seasons in Japan. The outfielder/first baseman was named to his second AL All-Star team in 1972. He hit 90 big-league homers, including 20 during his career year, 1973. In a city where toughness counts and quitting is shunned, May was cheered by the Sox faithful for his courage in making it back to the starting lineup. Make lemonade out of lemons? Hell no. Face big-league pitching with the stump of a thumb? That’s Chicago, baby.

Carlos May was born on May 17, 1948, in Birmingham, Alabama. When he was issued uniform number 17, he became the first – and still the only – major-leaguer to wear his birthday (month: May and day: 17) on the back of his uniform. “They picked my number for me,” said May, looking back in 2022. “So, when I came to spring training, at first, they gave me No. 29. But when I came up to the big club, they gave me No. 17. I was just glad to be there. They could have given me 100 – I was in the big league and that’s what I wanted.”1

Carlos was the younger of two sons – following his even more successful big-league brother, Lee May – born to Tommy and Mildred (née Goldfinger) May. Tommy worked in a mattress factory while Mildred was employed in a poultry farm. They divorced when the boys were young.

Carlos was five years younger than Lee but followed the same path. Carlos attended Birmingham’s A.H. Parker High School, and like Lee, was a multi-sport star (baseball, basketball, football). Although he was a captain and most valuable player of the football team in his senior year, May chose to pursue a career in baseball. “I was a running back and a punter and had received a scholarship offer from Southern University (in Louisiana),” said May. “I saw the size of some of those guys, 270-280 pounds, and thought baseball would be a lot healthier for me.”2

It turned out to be a wise decision. The powerfully built switch-hitting outfielder batted .352 for Parker High his senior year, “with a tremendous amount of power” from the left side.3 The Chicago White Sox, Kansas City A’s, and New York Yankees all sent scouts to Birmingham. May was drafted by the White Sox in the first round (18th pick overall) of the amateur draft on June 7, 1966. Scout Walt Widmayer signed May to his first contract, which included a $21,000 bonus.

May reported to Chicago’s rookie league team in Sarasota, Florida. He hit .426 in 16 games, which earned him a promotion to Deerfield/Winter Haven of the Class A Florida State League. He hit .153 in 37 games and committed six errors in the outfield.

In 1967, May was assigned to the Appleton (Wisconsin) Foxes of the Class A Midwest League where he gave up switch-hitting and batted strictly left-handed. A tremendous offensive season was cut short on July 28 when May was called up for six months of active military duty at Parris Island, South Carolina, with the U.S. Marine Corps.4 At the time, he was leading the league in hitting with a .338 batting average and was among the league leaders in home runs (10) and RBIs (48).

The layoff did not affect May the following season. He was sent to Lynchburg of the Class A Carolina League where he led the league in hitting with a .330 average. May added 13 home runs and 74 RBIs. “If May goes up there and hustles, he could make Lynchburg fans forget all the stars they have had in the past,” said a Lynchburg coach.5

After the conclusion of Lynchburg’s season, May was called up to the White Sox. He made his major-league debut in Baltimore on September 6, 1968. Starting in left field and batting third, May went 0-for-4 in Chicago’s 3-2 victory.

After finishing in fourth place in 1967 – but contending for the pennant until the final week – the White Sox slumped to ninth in 1968. May and Bill Melton, who was also promoted to the Sox in 1968, were being counted on to help turn the club’s fortunes around.

On February 8, 1969, May married the former Margaret Hubbard in Birmingham.6 They adopted an infant son, Luis Maurice, in August 1970.7 Another daughter, Elizabeth Marie, died at age three on July 10, 1976. She had suffered from brain damage since her birth.8

In spring training 1969, Chicago manager Al Lopez noted that May “hit every kind of pitch” and that “he goes to all fields.”9 The concern was May’s fielding ability. Despite playing the outfield in the minor leagues, fly balls seemed to be an adventure for him. But whatever concerns there may have been, his offensive abilities overshadowed them. Lopez penciled May in as his starting left fielder.

May got off to an explosive start in 1969, blasting two home runs and driving in three runs at Oakland on April 9. He duplicated the feat on April 16 in the home opener against Kansas City. “I don’t consider myself a home run hitter,” said May. “The most I ever hit in the minors was 13. The one I hit the first time up today, I was surprised I hit it that far. They were playing me around to the right and so I was trying to punch the ball over the third baseman’s head.”10

On May 1, Lopez stepped down as manager of the White Sox. He had been dealing with various maladies over the last couple of seasons. Longtime coach Don Gutteridge replaced him as manager. Gutteridge saw the potential in May. “Carlos has a lot of things going for him,” said the new skipper later that summer. “The material may still be crude and inexperienced, but he has a lot of assets. “For one thing, he’s strong – long-ball strong. Yet he’s fast. He has the speed that steals bases. You often don’t get that combination for a young player. And he knows the strike zone – something else that most youngsters lack.”11

May continued with his hot start to the season. At the All-Star break, he had 18 home runs and 56 RBIs and was batting .279. The All-Star Game was originally scheduled to be played on July 22, 1969, at RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C. However, a rainout pushed the game back one day. On that date, the May brothers made a piece of baseball history. Carlos was the lone representative of the White Sox. Lee, then first baseman for the Cincinnati Reds, was selected as a reserve player for the NL. It was the first time in All-Star Game history that two brothers opposed each other.

Carlos pinch-hit for John Roseboro in the bottom of the ninth inning, but Atlanta’s Phil Niekro struck him out, clinching the NL’s 9-3 win and their seventh straight victory over the junior circuit. “Lee was at first base and he had his glove over his mouth,” said Carlos, “he was laughing so hard at me. I’d never seen a knuckleball before; I didn’t know how to hit the thing!”12

On August 9, 1969, May reported to Camp Pendleton, California, to fulfill his two-week obligation to the U.S. Marine Reserves. On August 11, he suffered the severe injury that threatened his baseball career. “I was with a mortar detail,” said May. “The company was all supposed to fire a one-round volley; there were six of us (mortars). Sometimes it’s hard to tell when they all go off, who fired. The spotters didn’t say anything and I was told to clean the piece. That was my job as a gunner. I had an iron rod with a swab on the end when I pushed it down into the barrel. Our mortar didn’t go off and I pushed the shell that was still in there, down to the contact point and it fired. What took part of my thumb off was the iron rod being blown back up. I couldn’t get my hand out of the way.”13

The incident blew off part of May’s right thumb. He stayed in California to work with a hand specialist. After massage treatment and multiple skin grafts, the skin began to toughen up around the affected area of May’s right hand. “When I first went to the hospital, I felt sorry for myself,” said May. “Then I looked around. I saw guys with no eyes, guys with no legs, guys with half a head, guys who couldn’t talk, walk, hear, guys with no mind or half a mind. I began to think, ‘What am I griping about?’”14

Although May played in only 100 games in 1969, The Sporting News still named him as their American League Rookie of the Year. He finished the year with 18 home runs, 62 RBIs, and a .281 average.

It was not until January 1970 that May was able to leave the hospital for good. Wilson Sporting Goods created a special batting glove for his right hand. He also choked up on the bat to alleviate pressure on the hand. May made a full recovery and was ready to reclaim his left field position. “Carlos really showed me something,” said teammate Tommy McCraw. “He’s got great courage. If he didn’t have real guts, he’d be back in Chicago, not out here trying to play ball. I know he has pain every time he throws, but he keeps throwing anyway.”15

The 1970 season was not one to be remembered on the South Side. The White Sox set a franchise record for losses that was not eclipsed until the historically dreadful 2024 season. Chicago (56-106) finished a whopping 42 games behind first-place Minnesota (98-64). May, despite playing in a career-high 150 games (50 more than 1969), hit fewer home runs (12) and had only six more RBIs (68), though he batted .285.

Don Gutteridge stepped aside on September 1, 1970. Coach Bill Adair was named as interim manager, eventually handing the reins of the team over to Chuck Tanner on September 18. Tanner made two immediate changes in the Chicago lineup. He moved Melton from right field back to his customary position at third base. He then moved May from left field to first base. “I’m confident Carlos can adjust to the change,” said Tanner. “And with May on first, along with Melton on third, we’re going to go into next season tremendously improved defensively no matter what else happens.”16 Considering that May had never played previously at first as a pro, Tanner must not have thought highly of the incumbents, Gail Hopkins and McCraw, in the field.

Chicago general manager Roland Hemond acquired Jay Johnstone, Mike Andrews, and Rick Reichardt through various trades to bolster the White Sox attack. They climbed out of the AL West basement into third place (79-83 record) in 1971.

May was involved in one of the game’s rarest plays on September 18, 1971. At home against Los Angeles, Chicago had the bases loaded against starting pitcher Tom Murphy. May sliced a ball down the left field line that got past a diving Ken Berry. He raced around the bases for an inside-the-park grand slam. For the season May batted .294 with 70 RBIs in 500 at-bats. However, he led the league by committing 18 errors at first base.

May was moved back to left field in 1972 after Chicago obtained first baseman Dick Allen from the Los Angeles Dodgers for pitcher Tommy John and utility infielder Steve Huntz. Allen was a proven star in the NL, a power hitter who was bringing his big bat to the South Side. Led by this key acquisition, the White Sox battled Oakland all season long for division supremacy. On August 31, the Sox trailed the A’s by 1½ games. But Oakland pulled away in September, posting an 18-10 record for the month while the Sox played just above .500 with a 14-13 mark.

What started out as a potent lineup was diffused somewhat when Melton was sidelined in June; surgery was required to repair a herniated disc. Allen delivered as advertised, leading the AL in home runs (37) and RBIs (113) while tying New York’s Roy White in walks (99).

As for May, he posted a career-high in batting average, hitting .308, and added another aspect to his game: stealing bases. May swiped 23 in 1972 and credited Allen for his success. “Dick taught me a lot about baserunning,” said May. “He’d talk to me a lot about picking up signs from the pitcher, getting a good lead … things like that.”17

Optimism ran high for the White Sox in 1973. “I’m already convinced that this is the most powerful hitting team the Sox have had in their history,” said Tanner, “although I don’t know that you could call it a ‘Murderer’s Row’ in a sense. While we have great home run power, we also have balance of fine line-drive hitters, men like Pat Kelly. We have both power and .300 hitting in good balance in our lineup.”18

Melton returned to the lineup, but Allen suffered a hairline fracture of a bone in his right leg. Meanwhile, May set career high marks in home runs (20) and RBIs (96). Despite his output, though, the Pale Hose slid to fifth (77-85).

Over that year and the next, May began to experience pain in his legs. “He played on bad legs for the last two seasons,” said Tanner in May 1975. “He could hardly walk, but he wanted to play. I used to notice him going up stairs one leg at a time.”19 By his own admission, May’s play was lackadaisical. His offensive numbers dropped significantly in 1974 as he changed his strategy. May had tried to hit home runs in 1973 to make up for the loss of Allen. In 1974, his home runs dropped to eight, but that was also by design. Meanwhile, despite not swinging for the fences, his batting average dipped to .249.

In 1975, Tanner moved May back to first base on a part-time basis, mostly to save the wear and tear on his legs. He batted .271 and hit eight home runs. Chicago’s record dipped to 75-86, again finishing fifth in the AL West.

On May 18, 1976, Chicago dealt May to the New York Yankees for pitcher Ken Brett and outfielder Rich Coggins. Yankees manager Billy Martin used May mostly as a designated hitter. In 87 games, May batted .278. The Yankees broke a 12-year drought, returning to the postseason for the first time since 1964. “For me, the playoffs were a greater thrill than the Series,” said May, who went 2-for-19 in a combined seven games as a DH. “We played Kansas City and it went five games with Chris Chambliss winning it for us with a home run. That was an exciting moment. It was pandemonium. He steamrolled a couple of fans on his way to the plate. The World Series was not as thrilling because we were swept in four games by the Big Red Machine.”20

May played less in 1977, batting .227 in 65 games. He was sold by New York to the California Angels on September 16, 1977. As a result, he missed another postseason playing opportunity, but his Yankee teammates did not forget his contributions to their championship run in 1977. May was given a full share of $27,758 from the players’ winning pot,21 His last game in the majors came that October 2. In 10 years and 1,165 games, May hit 90 home runs, totaled 536 RBIs, and batted .274.

After the season, May signed on with the Nankai Hawks of Japan’s Pacific League. He played with the Hawks for four seasons (1978-1981). Although the club was never in contention, May played well. Returning to regular outfield duty, he averaged 22 home runs and 77 RBIs during his first three seasons.

After his playing days were over, May began his second career with the U.S. Postal Service. “I’ve worked there for over 20 years,” said May in 2004. “I was a mail carrier, now I work as a clerk. I enjoy it. Lots of times people come up and remember me and we talk about baseball and the White Sox.”22

From 1993 through 2025, May has worked in the Chicago White Sox front office in the Community Relations Department. He makes personal appearances and is an ambassador for White Sox baseball. “I came to Chicago in 1968 and haven’t left,” said May. “They have the greatest fans in baseball. I played with the Yankees and the Angels, but the White Sox are me. I am a Sox die-hard fan. It hurts me when they don’t do well.”

White Sox fans have fond memories of May. He’s one of them – a blue-collar player and an approachable person who wove himself into the fabric of the city of Chicago. They always remember the courage and determination he showed in returning from his injured right hand. There have been many great players who played on the South Side, but few who embraced the city as much as Carlos May has after his playing days were over. For that, he will always be held in high esteem by Sox fans.

Last revised: July 30, 2025

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bill Lamb and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Photo credit: Carlos May, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Mike Lowe, Kevin Doellman, “‘May Day’: Former White Sox all-star only player in MLB history to wear his birthday on his back,” WGN Channel 9, May 17, 2022, accessed June 15, 2025.

2 Mark Liptak, “Carlos May (2004),” SABR Oral History Collection, accessed April 6, 2025.

3 “Drafting four-Majors like Jeffco talent,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, June 8, 1966. 52.

4 Foxes Lose May to Marines for Six Months Active Duty,” Appleton (Wisconsin) Post-Crescent, July 24, 1967: 21.

5 Calvin Porter, “May Expected to Improve,” Lynchburg (Virginia) News, May 23, 1968: B-19.

6 Daniel Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1969: 3-1.

7 “A.L. Flashes,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1970: 34,

8 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1976: 49.

9 Richard Dozer, “May’s Bat Masks Glove,” Chicago Tribune, March 17, 1969: 3-2.

10 Robert Markus, “Steps Along the Sports Trail,” Chicago Tribune, April 17, 1969: 3-3.

11 Ed Rumill, “White Sox Finally Find Power Man in Carlos May,” Baseball Digest, September 1969: 33.

12 Liptak, “Carlos May,” SABR Oral History Collection, accessed May 3, 2025.

13 Liptak, “Carlos May,” SABR Oral History Collection, accessed May 3, 2025.

14 Jim Murray, “Carlos May Wins the Biggest Game of All,” Baseball Digest, October 1970: 76.

15 Jerome Holtzman, “No Maybe for May; He Can Throw,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1970: 12.

16 Edgar Munzel, “White Sox Expecting Success in Moving May and Melton,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1970: 30.

17 Liptak, “Carlos May,” SABR Oral History Collection, accessed May 3, 2025.

18 George Vass, “A New Murderer’s Row?” Baseball Digest, August 1973: 24.

19 Dick Dozer, “Every Day Is Like Mother’s Day to Carlos May,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1975: 16.

20 John Ralph, “Where Have You Gone, Carlos May?” Baseball Digest, September 2002: 65-66.

21 “Saga of Series Swag…$1,182 to $27,758,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1977: 57.

22 Liptak, “Carlos May,” SABR Oral History Collection, accessed May 3, 2025.

Full Name

Carlos May

Born

May 17, 1948 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.