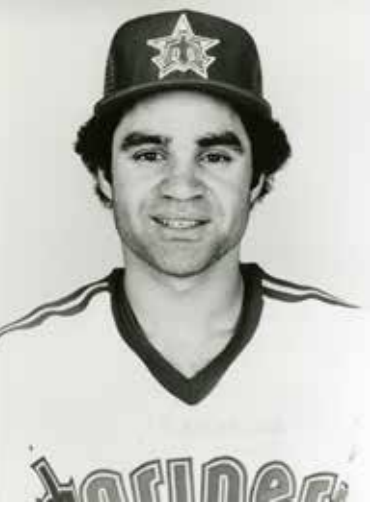

Julio Cruz

Julio Cruz made a strong statement about his value during a Seattle Mariners home game against the Cleveland Indians on June 7, 1981. Cruz’s glove and legs sparked Seattle in a 5-4 victory in 11 innings.1 He tied a major-league record for second basemen when he handled 18 chances without an error in nine innings.2 Cruz’s speed helped seal the win. With one out in the bottom of the 11th and the score tied, 4-4, he singled, stole second base, and scored the winning run on a single. After the game, Cruz told a reporter a player does not have to be a superstar to help his team.3

Julio Cruz made a strong statement about his value during a Seattle Mariners home game against the Cleveland Indians on June 7, 1981. Cruz’s glove and legs sparked Seattle in a 5-4 victory in 11 innings.1 He tied a major-league record for second basemen when he handled 18 chances without an error in nine innings.2 Cruz’s speed helped seal the win. With one out in the bottom of the 11th and the score tied, 4-4, he singled, stole second base, and scored the winning run on a single. After the game, Cruz told a reporter a player does not have to be a superstar to help his team.3

Julio Cruz never reached superstar status, but he enjoyed a notable career. The 5-foot-9, 160-pound second baseman spent 10 seasons in the major leagues, earning the nicknames “Cruzer” and “Juice.” Although Cruz exhibited weak hitting during his career, his rangy, acrobatic fielding and basestealing prowess helped him rise from undrafted free agent to steady major-league starter. He joined the Mariners midway through their inaugural season in 1977 and eventually emerged as a fan favorite because of his play and affable manner. He later helped spark the Chicago White Sox to a division title. Although a toe injury derailed his career, he had earned a place in baseball history. He joined a small group of players who achieved a career stolen-base percentage of at least 80 percent and at least 300 bases.

Julio Luis Cruz, of Puerto Rican descent, was born in Brooklyn, New York, on December 2, 1954, to Julio Luis Cruz and Lydia (Vargas) Cruz. He told the Chicago Tribune his father had left his mother during the eighth month she was pregnant with him. Cruz lived with his maternal grandparents, Raphael and Soledad Vargas, because his mother had to work.4 She found employment slipping bubble gum into Topps baseball-card packs. His mother eventually remarried, but Cruz’s grandparents insisted on keeping him.5

Cruz has several half-siblings. One, Ivan Cruz, played in the major leagues. An outfielder and first baseman, Ivan played 41 games for the New York Yankees, Pittsburgh Pirates, and St. Louis Cardinals between 1997 and 2002.

Julio Cruz’s love for sports started while he grew up in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. An uncle, Ralph Vargas, taught a 10-year-old Cruz the fundamentals of softball and took him to his softball games at a park near Cruz’s home. Vargas played in the outfield. Cruz played third base and struggled to lift a heavy bat.6 Away from the park, he listened to radio broadcasts of Yankees and Mets games, collected baseball cards and played ballgames with friends.7 His favorite baseball players included Pittsburgh Pirates great Roberto Clemente. Cruz especially liked Clemente because of his Puerto Rican heritage and generous nature. Clemente died on New Year’s Eve 1972 when his plane crashed en route to Managua, Nicaragua, carrying supplies for the victims of an earthquake. Cruz carried Clemente’s card in his wallet while he played in the minor leagues.8

Williamsburg, with plentiful factory jobs, attracted many Puerto Rican migrants. During the 1960s, however, job losses led to an increase in poverty, crime, and drug usage. The quality of life in the neighborhood sharply declined.

“I had two things to choose between in my life, hanging around on the streets or getting into trouble,” Cruz recalled. “A lot of kids thought I was chicken for playing baseball, but they changed their minds when they heard I was good at stealing bases. I wasn’t the best player in the neighborhood. I wasn’t even the best player on my block. But some of the better players hung out with the wrong group, and I never heard about them again. … We played a lot of stickball, that’s where you try to hit a rubber ball with a broomstick, and stoopball, where you throw the ball against the point of a stoop, and running bases, where you run between two bases.”9

His family, including extended relatives, fled the adverse conditions in Williamsburg. They flew to California in 1968 and settled in unincorporated Loma Linda, 60 miles east of Los Angeles in the San Bernardino Valley. Loma Linda is known for its high percentage of residents who are Seventh-day Adventists. Cruz’s maternal grandparents practiced the faith. Loma Linda was incorporated as a city in 1970. At the time, it had approximately 10,000 residents.10

Cruz attended Cope Junior High School (now Cope Middle School) in nearby Redlands, California, during the 1968-1969 school year. He played on a Senior Little League team called the Orioles, earning all-star honors in 1969. Between 1969 and 1972, he attended Redlands High School. He earned all-Citrus Belt League honors in both basketball and baseball.

Cruz played guard on the basketball court for the Terriers. Despite his short stature, he developed good passing skills and scored with drives to the basket and shots from long distance.

Another future sports star, Brian Billick, played forward on the e basketball team. Billick later played tight end at Brigham Young University and coached the Baltimore Ravens to victory in Super Bowl XXXV.

Cruz played shortstop and second base for the baseball team. Redlands baseball coach Joe DeMaggio (no relation to the New York Yankees legend) recalled that Cruz displayed special qualities during his high-school career. “We played him at short in his sophomore year,” DeMaggio said. “But I found out when I put him on second base that he had great natural talent, quickness, coordination, and leaping ability, all of which he developed through basketball. He was one of the best base stealers I’ve had.”11

No major-league team drafted Cruz after he graduated in 1972. Instead, he played for the Redlands American Legion Post 106 baseball team for two consecutive summers. He displayed his speed during a home game at Community Field against Apple Valley in June 1972. The score was tied, 6-6, in the bottom of the 10th inning. Cruz batted with two outs. He hit a slow groundball to second and sped to first base. A teammate scored the winning run on the play.12

That fall, Cruz attended San Bernardino Valley College. He played on the basketball team during his freshman year. He eventually graduated with an associate’s degree in liberal arts.

In January 1974, the California Angels drafted Redlands alumnus Juan Delgado. Delgado, an outfielder, had played with Cruz on the Little League, high-school, and American Legion baseball teams. He took Cruz to pickup games conducted by the California Angels on Sundays at the University of California at Los Angeles’s Sawtelle Field.13 After games, Angels scout Lou Cohenour treated him to hamburgers. Cohenour eventually offered to sign Cruz as an undrafted free agent.

Cruz hesitated to sign. He lived with his grandparents, who spoke only Spanish. He served as their translator. He worried about leaving them alone, but they gave him their blessing. He signed with the Angels.14

Afterward, Cohenour took Cruz to a sporting-goods store and bought him a glove and a pair of spikes as a bonus. Cruz later learned that draftees had received financial bonuses. The revelation foreshadowed his future salary battles with the Mariners and White Sox.

Cruz’s undrafted status motivated him to succeed. He started his professional career in Idaho Falls (Idaho), a rookie-level team in the Pioneer League managed by Larry Himes. Himes played a key role in Cruz’s career years later. The team paid Cruz $500 per month and provided $5 per day for meals. Cruz phoned his grandparents every day, racking up huge long-distance bills. Cruz batted .241 in 72 games and stole 34 bases.

Cruz liked to earn money while he played baseball, but he disliked other aspects of life in the Pioneer League. “I thought I’d get lost in the shuffle for a while,” he said. “You got paid $500 a month at the start and you spent most of your time on buses. The cities you were at weren’t too good and the fields you played on weren’t too good either. “Thank God I had the ability to get ahead.”15

The natural right-hander began to switch-hit after coaches told him it would help him advance to the major leagues. Cruz, however, struggled during the learning process. During his first attempt to bat left-handed, Cruz didn’t know how to handle the bat when coaches took him to a cage and tossed balls to him. Cruz also had trouble during games. He was hit by pitches seven times. “The toughest part was the ball being thrown at you,” he said. “I had nowhere to go. I got hit in the numbers, busted ribs. I took it personally after a while.”16

The next year, Cruz advanced to Quad Cities in the Class-A Midwest League. He improved to .261 and stole 60 bases. Only three pitches struck Cruz that season.

Playing for three minor-league teams in 1976, Cruz showed significant progress. He started the summer with Salinas (California) of the Class-A California League, and batted .307 with 68 stolen bases in 96 games. His 41 consecutive errorless games set a league record. Afterward, the Angels bumped Cruz up to El Paso (Texas) of the Double-A Texas League, for whom he batted .327 in 13 games with three stolen bases. Toward the end of the season, Cruz played 20 games with Triple-A Salt Lake City (Pacific Coast League). He batted .246 and stole 12 bases. Altogether, Cruz stole 83 bases.

Cruz displayed feisty behavior on the field during his time with Salt Lake City. The club hosted a best-of-five championship series against Honolulu, a San Diego Padres affiliate. In the fifth and deciding game, Honolulu’s Dave Hilton charged the pitcher’s mound after he struck out in the third inning. Both benches cleared and a brawl ensued. The Honolulu Advertiser said Cruz gave Hilton a cheap shot and was ejected from the game. Before he left the field, Cruz argued with opposing pitcher Mike DuPree. DuPree invited him to settle the dispute. Cruz accepted the invite. Both benches cleared again. Umpires restored order. Honolulu won the game, 3-2, and took the series.17

Though Cruz had emerged as one of the top prospects in the Angels farm system, the club left him unprotected in the November 1976 expansion draft. That decision helped Cruz because Jerry Remy had established himself as a solid starting second baseman for the parent club. The newly formed Mariners chose Cruz in the fifth round. They signed him to a one-year contract a month later.

Instead of competing with Remy, Cruz got a chance to shine for a brand-new team. He played well during spring training in 1977. The club, however, thought he needed more seasoning at Triple A, choosing Jose Baez to start at second base and trading for Larry Milbourne, a utility player. Because the organization did not have a Triple-A affiliate yet, it sent Cruz to Honolulu.

Cruz worried that the fans in Hawaii would boo him because of the rhubarb the previous season. His fear proved correct. The fans booed him on Opening Day.18 Cruz eventually won them over with a .366 batting average and 47 stolen bases in 75 games.

He found another benefit to playing in Hawaii. He met Rebecca Nickerson there. They married several years later. Three sons were born to the union: Austin, Alexander, and Jourdan. Rebecca died in 2007.19

Cruz’s statistics proved irresistible for the Mariners. While Hawaii was playing in Phoenix, the Mariners called up Cruz on July 4, 1977. The next night the Mariners hosted the Chicago White Sox in the Kingdome. The Mariners put Cruz in the leadoff spot for his debut. He hit two singles and scored a run as the Mariners lost, 6-2.

On July 14 Cruz’s mother and 35 other relatives and friends traveled from Loma Linda to Anaheim Stadium to see the Mariners play the Angels. Cruz asked teammates for extra passes in order to accommodate the group. He rewarded the travelers when he hit a single and triple and scored twice to help the Mariners win, 4-1.20

Cruz finished the 1977 season with a .256 batting average and 15 stolen bases in 60 games. Early in the next season, he beat out Baez for the starting job. Cruz slumped to .235, but stole a career-high 59 bases, second in the American League behind Ron LeFlore’s 68 for the Detroit Tigers. Cruz also led major-league second basemen with a .987 fielding percentage.

During the early years of the Mariners, Cruz and center fielder Rupert Jones helped each other on offense. Cruz most often batted leadoff and Jones batted fourth or fifth. When Cruz reached base, he signaled to Jones to indicate when he would run. “I would put a finger in my ear hole, and that meant I would go on that pitch,” Cruz said. “He would take the pitch or fake a bunt, just to give me that little edge. But it gave him a little edge, too, because the other teams all knew I was going to run and they would throw him fastballs.”21

In 1979, Cruz achieved two additional career highs: a .271 batting average and a .363 on-base percentage, but missed 54 games after tearing ligaments in his left thumb when he tripped while running to first base in a game against the visiting Tigers on June 4. He tore ligaments in his left thumb after he tripped while he ran toward first base. Playing in only 107 54 games, Cruz still stole 49 bases.

In an assessment of Cruz printed in The Sporting News at the beginning of the 1979 season, Seattle sportswriter Hy Zimmerman acknowledged that Cruz occasionally got picked off first and thrown out on steal attempts, but praised him anyway. “In trade talks, his name crops up quickly,” Zimmerman wrote. “But were the M’s to trade him, there’s a chance they might have to close the Kingdome’s doors. For Julio not only swipes bases, he steals hits from the enemy. His specialty is the diving stop on a sure hit and an almost simultaneous leap to his feet for the throw. Whereas Rupe Jones was the instant hero of the fans in 1977, that mantle now belongs to Julio, a bubbling, dynamic young man.”22

After the 1979 season Cruz filed for an arbitration hearing. He requested $130,000. The Mariners offered $95,000. The arbitrator sided with the Mariners. Cruz also filed for arbitration after the next three seasons, winning only once. The hearings, which occasionally became contentious, helped poison his relationship with the team’s management.

In 1980 Cruz batted an anemic .209. He still stole 45 bases. During the season, Steve Wulf described Cruz in an article for Sports Illustrated: “He is a great lover of basketball — he says he can dunk even though he’s 5’9″ — so he likes to take a jumping pivot at second base even when it’s not necessary. That’s given him a hot-dog reputation he doesn’t mind. … When he first came up, Julio had a tendency to take out his frustrations by swinging his bat at defenseless sinks and batting helmets. He has since calmed down. He is also one of the more popular Mariners, especially with children. ‘No child within reach of Julio escapes being swept into his arms,’ says Jack Carvalho, Seattle’s promotion director.”23

Cruz had established himself as a solid big-league player. Although he never won a Gold Glove, he ranked among the best-fielding second basemen in the majors. His inconsistent hitting, however, hampered his career. He explained the batting issues. “I was a good hitter in the minor leagues; twice I hit .300. I didn’t have any theories about hitting or anything, I just got up to bat and hit the ball. But when I got to the big leagues with the Mariners, they had instructors for everything. They had an infield instructor, a base-running instructor, a hitting instructor, and they all wanted me to do things differently than I had been doing. What I had been doing had gotten me to the big leagues, but I figured since they were already in the big leagues, they must know what they’re doing. I tried doing things their way.

“If I had been smarter, I would have told them to let me hit my way instead of changing, but I was really intimidated. I tried to do everything everybody told me to. I got very confused. I had no consistent way of hitting. I would change stances for different pitchers. I even wanted to change bats for different pitchers. I figured, if the pitcher can change baseballs because one didn’t feel good, I should change bats.”24

Meanwhile, the Mariners generated woeful records during their first several years. They finished the 1977 season under manager Darrell Johnson with a 64-98 record. From 1978 to 1980, they finished 56-104, 67-95, and 59-103.

Johnson was fired in August 1980, and was replaced by Maury Wills, the majors’ third African-American manager. The club hoped Wills, formerly an outstanding basestealer for the Los Angeles Dodgers, would provide a spark for the team. The opposite took place. Wills alienated nearly everyone on the team with his erratic behavior and incompetent leadership. In one awkward episode during a game against the Oakland A’s, Wills ordered Cruz to hold Rickey Henderson on second like a first baseman. Henderson stole third anyway.25 The Mariners fired Wills in May 1981 and replaced him with Rene Lachemann.

Despite Wills’ conduct, Cruz liked him. Wills had taken an interest in Cruz, teaching him how to steal against left-handed pitchers. Wills told him: “When they look at you and turn away, their next move is to go to first base. When they are looking straight at you, they are going to pitch.”26

In 1981 Cruz rebounded by batting .256 and stealing 43 bases in a season shortened by a players’ strike. On June 11 he tied the American League record for consecutive steals without being thrown out, getting number 32 in an 8-2 Mariners victory over the visiting Baltimore Orioles.27 The players strike began the next day.

The strike ended on August 9. The next day Cruz tried for number 33 in a row, but Angels catcher Ed Ott gunned him down to end the streak.

Cruz batted .242, notched a .316 on-base percentage, and stole 46 bases in 1982. He tied for second among American League second basemen with a .987 fielding average, just .001 under Detroit’s Lou Whitaker. On May 6 he helped Mariners pitcher Gaylord Perry defeat the visiting New York Yankees, 7-3, and earn his 300th career win. Cruz scooped up a grounder by Willie Randolph and fired to first for the final out. “The biggest thrill I had when I was playing with the Mariners was being on the field when Gaylord Perry, the greatest spitball pitcher of all time, won his three-hundredth game. Man, when there were two outs, I was really nervous. I kept reminding myself, Cruiser, if the batter hits it to you, make sure you grab the ball on the dry side.”28

Cruz and shortstop Todd Cruz (no relation) earned plaudits in the New York Times for a spectacular game-ending double play on July 21, 1982, against the Yankees at Yankee Stadium. The Mariners led 6-5 in the bottom of the 12th inning. With one out and runners on first and second, Dave Winfield hit a sharp grounder up the middle. Cruz was playing toward the right side, but scurried to his left. He dived, backhanded the ball, and tossed it to the shortstop, who got the force out and threw out Winfield on a very close play to end the game.29

That season Cruz also displayed kindness off the field. A woman told Cruz that she had cancer during their chat at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. Cruz came to the hospital for her next chemotherapy session, brought her a Julio Cruz baseball shirt and tickets for her family to attend a Mariners game. Years later, the woman’s son, Skip Kulle, wrote about Cruz’s kindness for the Seattle Times. “Julio became a regular visitor to my mother’s bedside until she succumbed to cancer in December of that year. Sitting amidst our family at her memorial service was Julio Cruz.”30

On May 24, 1983, Cruz swiped a team-record four bases against the visiting Indians.31 The Mariners, however, figured the team would lose Cruz in free agency without compensation after the season. They traded Cruz to the White Sox for second baseman Tony Bernazard on June 15. Cruz had finalized the purchase of a home in Bellevue, Washington, on the e day. He left with a then club-record 290 steals. (That record has since broken by Ichiro Suzuki, who stole 438 during his first stint with the Mariners, from 2001 to 2012.)

The White Sox announced the trade on the Comiskey Park scoreboard during their game against the California Angels. Bernazard was a fan favorite, and White Sox fans in the crowd of 24,561 booed at the news. The White Sox had a 28-32 record at the time of the trade. Cruz helped spark the team to a 71-31 record after the trade. The White Sox won the American League West championship by 20 games over Kansas City. Cruz played in 99 games, batting.251 with 40 RBIs and 24 stolen bases. He scored the winning run in the clinching game against the visiting Mariners at Comiskey Park on September 17, on a sacrifice fly by Harold Baines.

“As I scored, everyone broke out of the dugout and ran onto the field to celebrate,” Cruz recalled. “Before I joined that celebration, I looked into the Mariner dugout. Everybody was sitting on the top step watching the Chicago players jumping up and down. At that moment, when I was so happy, I was also sad for them. I had played with those guys for six years, and I wished very much that they could all experience the e feelings I had running through my body.”32

The White Sox lost the American League Championship Series, three games to one, to the eventual World Series winner Baltimore Orioles. Todd Cruz, who had moved on from Seattle to Baltimore in June, started at third base for the Orioles. The Orioles pitchers stifled the Sox bats, but Julio Cruz batted .333 and reached base three times on walks for a .467 on-base percentage.

After the season, Cruz filed for free agency. Tense negotiations with the White Sox dragged on for two months. Cruz ended talks with the team and negotiated with the Angels. After White Sox broadcaster Hawk Harrelson talked to Cruz, the latter signed a six-year contract with Chicago worth between an estimated $3.6 million and $4.8 million.

Cruz received a big payday. After he signed the contract, however, his career declined. In 1984 he slumped to .222 with 14 stolen bases. He made a career-high 18 errors. Fans booed Cruz.33 The White Sox finished the season 74-88.

In 1985 Cruz slipped even further as an injured right big toe affected his play. He could not push off his right foot. He batted only .197 and stole 8 bases in 91 games. The team shifted him to platoon status with Scott Fletcher.

Cruz gave one of his final great plays early in the season against the Yankees’ Dave Winfield at Comiskey Park. Cruz dived behind second base to grab a groundball by Winfield, and flipped the ball out of his mitt to shortstop Ozzie Guillen. Guillen caught the ball barehanded, tagged second for the force and gunned the ball to first to beat Winfield. The White Sox won, 5-4, in 11 innings.34

Cruz showed promise in 1986 when he hit .359 during spring training, but he suffered a leg injury early in the season and landed on the disabled list.35 He batted only .215 and stole seven bases in 81 games.

From 1984 through 1986 Cruz played in only 315 of a possible 486 games. In 1985 and 1986 he landed on the disabled list three times. After three toe operations, he had lost his speed.36

By October 1986, Larry Himes, who had managed Cruz at Idaho Falls was the White Sox general manager. He traded for second baseman Donnie Hill, intending him to take the starting sport. Himes also traded for two backups.37

The team had hoped Cruz would play well and attract interest from other teams during spring training in 1987. Cruz, however, hit only .200. Himes told him the White Sox would release him. Cruz said: “If there’s one thing I have a chip on my shoulder about, it’s that I couldn’t contribute like in ’83. Because of the foot, I wasn’t able to be myself. In the back of my mind, I wonder what if I had never sustained the foot injury. There are a lot of ‘what ifs.’”38

Cruz finished his major-league career with a batting average of .237 and 343 stolen bases, a success rate of 81.5 percent. Only 28 players with at least 300 stolen bases have a higher percentage.

After his release, Cruz had a brief stint with Albuquerque, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ team in the Pacific Coast League. The Kansas City Royals invited Cruz to spring training in 1988, but he rejected their request that he join their Triple-A team. Cruz retired, then changed his mind.39 He briefly played for the Fresno Suns of the Class-A California League, then retired for good.

The game took a physical toll on Cruz. He spent much of his major-league career playing on Astroturf in Seattle. He said playing on the surface had hurt his right toe. Since retirement, he has endured eight operations on his knees. He has an artificial left knee. As of 2018, his right toe still hurt.40

After retiring, Cruz coached in the Mariners and Milwaukee Brewers organizations. In 1997 he led Pulaski, a Texas Rangers farm club, to a first-place finish in the West Division of the rookie-level Appalachian League and was named Manager of the Year. Cruz left after the one season because he wanted to work closer to his family. He and Bill Caudill coached the baseball team at Eastside Catholic High School in mamish, Washington. All three of Cruz’s sons played for the squad. Cruz has conducted youth baseball clinics. He has served as a color commentator for broadcasts of Mariners home games on the team’s Spanish-language network. He has represented the Mariners at community events.41

In 2002, Cruz was inducted into the Redlands High School Hall of Fame. In 2004 Cruz was inducted into the San Francisco-based Hispanic Heritage Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2016 he was honored by SEAT 21, an MLB program that recognizes people who emulate Roberto Clemente’s humanitarian spirit. Cruz supports Toys for Kids, which raises money to buy holiday gifts for homeless and hospitalized children.42 In 2017 he was recognized at Julio Cruz Day hosted by the Chelan County Public Utility District in Wenatchee, Washington.43

Cruz settled in Redmond, Washington, with his second wife, Mojgan Moini. He spends time with his granddaughter. He does Mariners Spanish-language broadcasts on Fridays and Saturdays. He occasionally gives baseball clinics at high schools.

Cruz maintains his love of basestealing. Shortly before he received the SEAT 21 honor, he visited Auburn High School in Kent, Washington. Cruz had intended to stay about 20 minutes. Instead, he talked for close to an hour. He discussed stealing with the school’s baseball team. He emphasized that successful baserunning partially results from observation. To prove his point, he stood on the pitcher’s mound and showed how a right-hander might relax his shoulders and release air before he delivers the ball. “Once you see the lean,” Cruz told the players, “you must get going.”44

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

The author wants to thank Julio Cruz for sharing his story. The author also would like to thank the following for their assistance: Jim Corcoran, co-owner/general manager Wenatchee AppleSox Baseball Club; Rebecca Hale, director of public information, Seattle Mariners; Suzanne Hartman, communications manager, Chelan Public Utility; Tim Herlich, treasurer, Northwest SABR chapter; Cassidy Lent, reference librarian, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and William Wade Norris, San Bernardino Valley College.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-almanac.com, Baseball-reference.com, Bklynlibrary.org, Newspapers.com, Retrosheet.org, Paperofrecord.com, Julio Cruz’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, and the following:

Anderson, Claude. “Area Players Sparkle in Minors,” San Bernardino County Sun-Telegram, November 6, 1975: E-3.

Anderson, Claude. “Page’s Latest Chapter on Bicycle Trek Proves It’s Not a Dog’s Life,” San Bernardino County Sun-Telegram, July 12, 1977: B7, B8.

Buchan, Jim. “Baseball Hunch — Bet on the American League,” Walla Walla (Washington) Union-Bulletin, June 30, 1983: 17.

Dilbeck, Steve. “Cruz One of Best Ballpark Hot Dogs,” San Bernardino County Sun, March 14, 1979: D-1, 4.

Feinstein, John. “Happiest Mariner Is the Manager,” Washington Post, August 9, 1980. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

Holtzman, Jerome. “LaRussa May Be Next to Go,” Chicago Tribune, June 19, 1983: B3.

Hulse, Gilbert. “Julio Cruz Wants to Improve His Staying Power,” San Bernardino County Sun-Telegram, March 14, 1978: B-7, 10.

Lane, Jeff. “Cruz Leads Mariners to Win Over Angels,” Redlands (California) Daily Facts, July 15, 1977: 7.

Ringolsby, Tracy. “M’s Certain They Picked a Gem in Moore,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981: 39.

Ringolsby, Tracy. “‘Secure’ Zisk Feels Obligation to Strike,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1981: 39.

Schulian, John. “Brooklyn Stickball Groomed Cruz for Sox,” Palm Beach Post, May 30, 1984: D2.

Stone, Larry. “Cruz Just the Hombre for M’s Spanish Radio Cast,” Seattle Times, February 7, 2003. Source: National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Wigge, Larry, ed. The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide 1983 (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Company, 1983).

“Ryan Ties Strikeout Mark in Win Over A’s,” Redlands Daily Facts, July 5, 1977: 9.

The Sporting News March 7, 1988: 21.

Notes

1 Kirby Arnold, Tales from the Seattle Mariners Dugout: A Collection of the Greatest Mariners Stories Ever Told (New York: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2007, 2014), 18.

2 The Philadelphia Phillies’ Terry Harmon set the record in 1971.

3 “The Seattle Mariners’ Julio Cruz says you don’t have…,” United Press International, June 7, 1981.

4 Mike Kiley, “Both Love and Money Kept Cruz with the Sox,” Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1984: 4, 1 and 2.

5 Phone interview with Julio Cruz, April 9, 2018.

6 Phone interview with Julio Cruz, April 17, 2018.

7 Bill Virgin, “In Spanish Broadcasts, Cruz Has Bases Covered,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 5, 2004. Retrieved October 22, 2017; Ross Foreman, “Julio Cruz,” Sports Collector’s Digest, February 9, 1996: 130-131; Ron Luciano and David Fisher, The Fall of the Roman Umpire, (New York: Bantam Books, 1986), 299.

8 Phone interview with Julio Cruz, April 17, 2018.

9 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, 297-299.

10 “Voters Approve City of Loma Linda,” San Bernardino County Sun, September 23, 1970: B-1.

11 Joyce Hall, “Go-Go Cruz Has Finally Found a Stopping Place,” San Bernardino County Sun-Telegram, July 5, 1977: B-8.

12 George Andrews, “Redlands Legion Wins in Extra-Inning Game,” Redlands Daily Facts, June 5, 1972: 15.

13 UCLA built Jackie Robinson Stadium on the site of Sawtelle Field. The stadium was dedicated in 1991.

14 Phil Fuhrer, “Julio Cruz Translates Baseball Talent,” San Bernardino County Sun-Telegram, November 3, 1974: E-4.

15 Paul Oberjuerge, “Clearly, Julio Is Cruzin’ in the Majors,” San Bernardino County Sun-Telegram, July 17, 1977, E-1, E-7.

16 Larry Stone, “The Art of Baseball: Flipping the Switch,” Seattle Times, July 16, 2006. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

17 “They Won When They Had To,” Honolulu Advertiser, September 13, 1976: D-1, D-3.

18 Rod Ohira, “Islander Gem,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 3, 1977: C-2.

19 Phone interview with Julio Cruz, April 17, 2018.

20 Terry Greenberg, “Cruz’ Fan Club Lives It Up,” Redlands Daily Facts, July 15, 1977: 7.

21 Kirby Arnold, 16.

22 Hy Zimmerman, “Julio Cruz to Run for More Money from M’s,” The Sporting News April 14, 1979: 51.

23 Steve Wulf, “Choose Which Cruz Is Whose,” Sports Illustrated May 5, 1980. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

24 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, 302-303.

25 Michael Emmerich, 100 Things Mariners Fan Should Know & Do Before They Die (Chicago: Triumph Books LLC, 2015), 252.

26 Phone interview with Julio Cruz, April 17, 2018.

27 Vince Coleman of the Cardinals set the record with 50 consecutive steals in 1988. Ichiro Suzuki of the Seattle Mariners set the American League record of 45 consecutive steals in 2007.

28 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, 306.

29 Joseph Durso, “Plays; Double Play Executed with Flair,” New York Times, July 23, 1982. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

30 “Thanks for the Memories,” Seattle Times, June 27, 1999. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

31 Since then, Henry Cotto, Mark McLemore, Harold Reynolds, and Ichiro Suzuki (twice) have tied the team record.

32 Ron Luciano and David Fisher, 307.

33 Mike Kiley, “Cruz’s Bubble Punctured by Fan Reaction,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1984: D3.

34 Mike Kiley, “Sox Just Too Tough to Lose,” Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1985: Section 4, 1 and 14.

35 Ed Sherman, “Cruz Eager to Test Leg, Bat in Detroit on Weekend,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1986: C6.

36 Dave van Dyck, “Cruz Primed to Fight for Job,” Chicago Sun-Times, February 10, 1987: 92.

37 Ibid.

38 Dave van Dyck, “Cruz Sent Packing by Sox,” Chicago Sun-Times, March 24, 1987: 96.

39 David T. Bristow, “New Beginning for an Old Ballplayer,” San Bernardino County Sun, May 20, 1988: C2.

40 Phone interview with Julio Cruz, April 17, 2018.

41 Larry Stone, “Cruz Just the Hombre.”

42 “Robinson Cano and Julio Cruz Honored on Roberto Clemente Day,” Seattle Mariners Baseball Information Department, September 6, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

43 E-Mail correspondence with Suzanne Hartman, April 5, 2018.

44 Chris Chancellor, “Trojans Ride Around Diamond with Mariners’ Legend,” Auburn Reporter, April 20, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

Full Name

Julio Louis Cruz

Born

December 2, 1954 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.