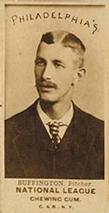

Charlie Buffinton

To paraphrase one nineteenth-century baseball scholar, Charlie Buffinton, while perhaps not a truly great pitcher, was unquestionably a very good one.1 Possessed of poise, baseball intelligence, and a knee-bending 12-to-6 overhand curve (then called a drop), Buffinton racked up 233 wins in his 11-season major-league career.2 He also appeared in over 200 more games as an outfielder or first baseman. Only 31 when he abruptly left the game in midseason 1892, Buffinton spent the remaining 14 years of his too-short life engaged in his family-connected coal brokering business. After his death in 1907, Buffinton quickly receded from memory, and drew not even a passing nod when the Hall of Fame opened its doors some three decades later. Nor has he received much attention since. To try to fill that void, the ensuing paragraphs look back at the life and baseball exploits of this underappreciated, largely forgotten standout of the early game.

To paraphrase one nineteenth-century baseball scholar, Charlie Buffinton, while perhaps not a truly great pitcher, was unquestionably a very good one.1 Possessed of poise, baseball intelligence, and a knee-bending 12-to-6 overhand curve (then called a drop), Buffinton racked up 233 wins in his 11-season major-league career.2 He also appeared in over 200 more games as an outfielder or first baseman. Only 31 when he abruptly left the game in midseason 1892, Buffinton spent the remaining 14 years of his too-short life engaged in his family-connected coal brokering business. After his death in 1907, Buffinton quickly receded from memory, and drew not even a passing nod when the Hall of Fame opened its doors some three decades later. Nor has he received much attention since. To try to fill that void, the ensuing paragraphs look back at the life and baseball exploits of this underappreciated, largely forgotten standout of the early game.

Charles G. Buffinton was born on June 14, 1861, in Fall River, Massachusetts, a then-bustling textile mill center located about 50 miles south of Boston. He was the older of two sons born to teamster, later businessman, John E. Buffinton (1837-1910) and his wife, the former Phebe Morse (née Kelley, 1831-1895), both originally from Rhode Island.3 Little is known of Charlie’s early life, but by the time he was a teenager, he had found employment as a clerk at a local grocery store.4 Tall (6-feet-1), sturdily built (180 pounds early in his career, later much heavier), and athletic, the youngster first attracted notice playing ball for Fall River-area amateur baseball clubs. The competition was fierce and talent abounded. At one time or another, Buffinton’s hometown teammates and/or opponents included future major leaguers Jim Manning, Mert Hackett, Tom Gunning, Frank Fennelly, Chris McFarland, and Andy Cusick.5

A right-handed batter and thrower, Buffinton began his career as a maskless catcher for teams in and around Fall River until a bruising foul tip over the eye induced him to look for another playing position.6 His initial stab at pitching, however, was not a success, as he was pounded by a New Bedford nine. Undiscouraged, Charlie stayed with it, improved, and bested New Bedford in two subsequent outings. By 1879 he was alternating between pitching and first base for a Fall River club called the Quequechans.7 And with future major-league batterymate Gunning behind the plate, Buffinton pitched the Q’s to the Massachusetts state championship that October.

A year later, Buffinton entered the professional ranks, signing to play the 1881 season with Al Reach’s Philadelphia club, then an independent outfit affiliated with the League Alliance.8 Unhappily for the now-21-year-old prospect, he saw action in just four games as an outfielder before being released by Philadelphia. In 1882 Buffinton got another chance. Signed by the Boston National League club, he spent most of the season playing with the club’s reserve team against lesser competition. He was, however, auditioned early by the parent club. On May 17, 1882, Charlie debuted impressively, throwing a 4-0 shutout at the NL Worcester Ruby Legs. He registered another victory over Worcester the following day, but lost his three subsequent starts and was soon back with the reserves. His final record for NL Boston that season was 2-3, with a high 4.07 ERA in 42 innings pitched. Buffinton was worse in seven games in the Boston outfield, making five errors in 13 chances (.615 FA), but posted a respectable .260 (13-for-50) batting average in 15 major-league games played, overall. Notwithstanding his marginal stats, the good-sized Buffinton was young and had shown enough to warrant Boston re-signing him for the next season.9

Buffinton blossomed in 1883, ably supporting hurling partner Jim Whitney in a pennant-winning (63-35) Boston campaign. Between them, Grasshopper Jim (37-21, with a 2.24 ERA in 514 innings pitched) and blond-mustached Charlie (25-14, with a 3.03 ERA in 333 innings pitched) started every game for Boston except one.10 Years later, famed Boston sportswriter Tim Murnane recalled, “Whitney had tremendous speed, and Buffinton had mastered a drop that fell into the hands of his catcher like a snowflake.”11 Stationed in the outfield and occasionally at first base when Whitney was in the box, Buffinton also chipped in a .238 batting average, with 28 runs scored and 26 RBIs for the champs. But his fielding, particularly in the outfield, (20 errors in 51 games, .756 FA), remained a liability.

The following year saw Buffinton attain the summit of his career. With arm fatigue and nagging injuries precipitating a significant reduction in Whitney’s numbers, Charlie supplanted him as Boston’s ace, taking the ball 67 times. He proved more than up to the task, turning in a stunning 48-16 record, with career bests in innings pitched (587), strikeouts (407, compared with only 76 walks issued), and shutouts (8). He also upped his batting numbers, hitting .267 with 39 RBIs in 87 games played, total. Regrettably for our subject, his heroic work was overshadowed by the historic performance of a pitching rival, Providence ironman Hoss Radbourn. In the course of leading the Grays to their only National League crown, Radbourn posted an all-time major-league single-season record 60 victories, and led the circuit in innings pitched (678⅔), complete games (73), ERA (1.38), strikeouts (441), and winning percentage (.833) for good measure.

The logs of both Buffinton and his Boston club declined markedly in 1885. Yet while his individual won-lost record fell to 22-27, Charlie still turned in a first-rate 2.88 ERA over a yeoman 434⅓ innings pitched for a fifth-place (46-66) club. And salving the sting of a disappointing baseball season was a highlight in Buffinton’s personal life: his marriage to English-immigrant mill worker Alice Thornley. In time, the couple would have three children: Phebe (born 1886), Charles (1892), and Alton (1893).

Buffinton had thrown more than 1,350 innings over three seasons, which took their inevitable toll on his pitching wing. Plagued by shoulder problems, Buffinton played more games at first base and the outfield (29) than he pitched (18) in 1886. And he was hit hard when he was able to pitch: 203 base hits surrendered in only 151 innings pitched, leading his ERA to balloon to 4.59 ERA, He went 7-10 for a 56-61 club that repeated its fifth-place finish in the NL standings. Both were a sore disappointment to club brass, and changes were rumored in the offing for next year. Soon, reports of Buffinton’s likely departure from Boston surfaced in the press.12 Nor did the former staff mainstay endear himself to principal club owner Arthur Soden in the ensuing offseason. Buffinton served on the executive council of the Base Ball Players Brotherhood, the fledgling players union organized by visionary New York Giants shortstop John Montgomery Ward.13 In stark contrast, Soden was author of the restrictive reserve clause in the standard player contract.

Just before the start of the 1887 season, rumor became fact when Buffinton and batterymate Tom Gunning were sold to the NL Philadelphia Phillies at a bargain price ($500).14 But Buffinton was likely still sour toward Philadelphia co-owner Al Reach after being released in 1881. He initially balked at returning to the City of Brotherly Love and threatened not to report.15 He soon changed his mind, however, and accepting the transfer to Philadelphia rejuvenated Buffinton’s pitching fortunes.

Astute Phillies manager Harry Wright did not overtax his new hurler’s sometimes fragile pitching arm. Instead, he fitted Buffinton into a three-man rotation with youngsters Dan Casey and Charlie Ferguson. Wright also reduced Buffinton’s role as an offday outfielder-first baseman. From then until the end of his major-league career, Buffinton’s appearances as a field player became increasingly infrequent, much to the benefit of his pitching stats.

The Phillies and Buffinton began the new season unimpressively. And by early August, the record of the club (38-38) and Buffinton (10-12) remained mired in mediocrity. Then, both suddenly caught fire. The Phillies went a sizzling 37-10 down the stretch, with Buffinton contributing 11 of the victories. Philadelphia closed the campaign with a 17-game winning streak (with one tie) to vault into second place, only 3½ games behind the NL champion Detroit Wolverines. Buffinton’s final stats (21-17, 3.66 ERA) were not as gaudy as those of Casey (28-13, 2.86) and Ferguson (22-10, 3.00), but his 332⅓ innings pitched demonstrated fully recovered arm strength.

During the offseason, Buffinton admitted surprise at the contentment that he had found in his new surroundings. He “had no idea when he came to Philadelphia that he would find it such a pleasant place,” and maintained that he “never received better treatment or made more friends” than he had in Philly.16 Charlie’s only regret was the Phillies’ recent release of his hometown friend and personal catcher Tom Gunning.17

The Phillies were stunned by the tragic death of 25-year-old phenom Charlie Ferguson in late April 1888.18 They never recaptured their late-season form of the previous year. But little of Philadelphia’s fall to a third-place (69-61) finish was the fault of Buffinton, He went 28-17, with an eye-catching 1.91 ERA in a shade over 400 innings pitched. He struck out 199 and posted a career-best WHIP (0.957). The situation pretty much repeated itself in 1889. Buffinton was again outstanding, going 28-16 (.636), albeit with a higher 3.24 ERA in 380 innings pitched, for a losing 63-64 (.494) Phillies club.

As the 1889 season progressed, rumbles of player insurrection intensified. And soon after the campaign’s completion, the Brotherhood went public, announcing the formation of a new, player-controlled major-league circuit, the Players League. Ardent unionist Buffinton was among the first to declare his allegiance to the upstart organization, signing with the Players League’s Philadelphia Quakers.19 Indeed, it was subsequently reported that he was a modest investor in the franchise.20 Phillies co-owner and prominent Philadelphia attorney John I. Rogers responded by seeking judicial relief enjoining Buffinton and a fellow club jumper, second baseman Bill Hallman, from playing for anyone other than the Phillies. Although neither Buffinton nor Hallman had signed an 1889 season contract with the Phillies, Rogers maintained that the pair were nonetheless bound to his club by an automatic rollover reserve clause contained in the Phillies contracts that they had signed in October 1888.21 Ultimately, the argument failed to impress. In Philadelphia, as elsewhere, the players prevailed in court and were granted leave to join the Players League for the 1890 season.

With three major leagues (National League, American Association, and Players League) competing for talent, clubs were not always star-studded. Easily the biggest name on the PL Philadelphia roster was former NL pitching stalwart Charlie Buffinton, now up to a heavyweight 210 pounds.22 The post of Quakers playing manager, however, went to another Phillies defector, outfielder Jimmy Fogarty. He lasted 16 games, resigning the helm after the Quakers got off to a 7-9 start.23 Although no official explanation was provided, rumor had it that Fogarty had quarreled with Philadelphia club President Harry Love24 or that Fogarty was ill.25 But at least one report had a row with star pitcher Buffnton as the reason Fogarty quit.26 If so, the event was a singular one — the sober, conscientious Buffinton enjoyed a career-long reputation as an affable teammate and a gentleman, widely respected by fellow players, club owners, and the sporting press.

Whatever the reason for Fogarty’s resignation (and he remained with the club as an outfielder), Buffinton was handed the reins of the Philadelphia club. Applying the lessons of personal experience, the new skipper did not attempt to shoulder the brunt of the hurling burden. Rather, he spread it around, giving youngsters Ben Sanders and Phil Knell every bit as much pitching work as he took on himself. The results weren’t good enough for pennant contention — the Quakers went 61-54 under Buffinton’s command and finished fifth. Yet they were respectable: Knell, 22-11 in 286⅔ innings pitched; Sanders, 19-18 in 346⅔ innings pitched; and Buffinton, 19-15 in 283⅓ innings pitched.

Manager Buffinton would get no chance to build on the foundation that he had laid in Philadelphia, as the financially ailing Players League had taken to its deathbed. In late October, Buffinton was among the circuit leaders who assembled for a postseason strategy meeting in Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue Hotel.27 But by then the Players League was doomed, the merger of the NL New York Giants and PL New York Giants franchises having sealed its fate. And by late November, triumphant Chicago club boss Albert G. Spalding, the head of the NL’s war committee, could accurately proclaim, “The Players League is as dead as the proverbial doornail.”28

Once the renegade circuit was interred, the rights to those who had jumped to the Players League reverted to the National League and American Association clubs that they had abandoned.29 But over the winter a dispute arose over the signing of two former Philadelphia AA players by NL teams. When the matter was not resolved to Association satisfaction, the circuit withdrew from the National Agreement and entered into ill-advised competition for playing talent with the much stronger National League. One beneficiary of the situation was Charlie Buffinton, who brushed off the Phillies’ old reserve clause claim to him and signed with the Boston Reds of the AA.30

The Reds, with future Hall of Famers Dan Brouthers and Hugh Duffy in the lineup, were a strong club. Most of their AA competitors were not. Paired in a dominant two-man rotation with fellow right-hander George Haddock (34-11, with a 2.49 ERA in 379⅔ innings pitched), Buffinton posted one of his finest seasons. He led the league with his .763 winning percentage (29-9) and 1.163 WHIP, while his 2.55 ERA (in 362⅔ innings pitched) ranked third. Meanwhile, Boston (93-42) cruised to the AA crown, but the Association’s estrangement from the National League precluded a postseason World’s Series between Boston’s two circuit champions.31

During the winter of 1891-1892, the fate of the financially troubled American Association was a topic of much discussion in baseball weeklies.32 Eventually, interleague negotiations yielded an agreement under which the National League absorbed four AA franchises.33 The remaining Association clubs, including the champion Boston Reds, disbanded. Disposition of the rosters of defunct Association clubs was entrusted to the tandem of NL President Nick Young and outgoing AA President Zach Phelps.34 Unhappily for Buffinton, he was assigned to an undertalented, shakily financed AA-remnant club in Baltimore.35

Buffinton began the 1892 season reportedly nursing a sore shoulder36 and 20 pounds overweight.37 Whatever the cause, his pitching was little better than the generally rotten play of the Baltimore club. In 13 games he went 4-8, with a career-worst 4.92 ERA, and was regularly hit hard (130 base hits allowed in only 97 innings pitched). With Baltimore destined for dead last (finishing 46-101) and drawing poorly,38 economies in the form of player salary cuts were proposed. In Buffinton’s case, he was assessed a 37.5 percent pay cut, from $400 to $250 per month, which he refused to accept. The club thereupon released him,39 bringing Buffinton’s professional career to a close just after he had celebrated his 31st birthday.40

Though he has been long overlooked by Cooperstown gatekeepers, a borderline Hall of Fame case can be made for Charlie Buffinton. During the course of 11 major-league seasons, he compiled an outstanding 233-152 (.605) record, with a 2.96 ERA over 3,404 innings pitched. Although fouls were not counted as strikes during his time, Buffinton still registered 1,700 strikeouts, while walking only 856. His 351 complete games included 30 shutouts. He also appeared in over 200 games in the field, although he was a poor defensive outfielder (career .727 FA in 137 games). But in over 2,200 at-bats, Buffinton hit a respectable .245, with 90 extra-base hits and 255 RBIs. While such numbers hardly place him in the Mathewson–Johnson–Young class, there is also no shortage of Hall of Fame honorees with credentials less impressive than Buffinton’s.41

Upon his return home to Fall River, Buffinton took a front-office position with a family-connected business, the Bowenville Coal Company.42 There were also reports that he was doing some spare-time pitching for area amateur clubs under the alias Brown.43 If so, he soon gave it up, limiting his postcareer involvement in the game to taking in the odd minor-league contest and occasionally attending team reunions in Boston.

For the remainder of his life, Buffinton lived and worked in Fall River, and was an active member of local civic and fraternal organizations. By all accounts, he was a faithful husband, doting father, and model citizen. About the only thing interfering with the good life for Buffinton was recurring, sometimes excruciating, pain in his right side.44 His physicians suspected gallstones and recommended exploratory surgery. Reluctantly, Buffinton agreed, and was admitted to the private hospital of Dr. N.B. Aldrich in late September 1907. The day before the scheduled operation, the patient “felt so well that he hesitated about going to the operating table … when he suddenly collapsed, suffering the most intense pain and becoming unconscious almost immediately.”45 He died the following morning, September 23, 1907. Charles G. Buffinton was only 46.

Autopsy posited the cause of death as coronary artery and tricuspid valve heart disease, with gallstones listed as a contributing factor.46 The sudden demise of the well-liked and seemingly healthy Charlie Buffinton stunned the local community. Among the grief-stricken was the county medical examiner: Dr. Thomas F. Gunning, longtime friend and former batterymate of the deceased. Said Gunning, “Charley Buffinton was one of the greatest pitchers that the game has developed. He and I grew from boyhood together. We played together on the Boston Nationals and in Philadelphia, he as a pitcher and I as a catcher. … After playing in Baltimore, Charley retired from the game with his prestige unimpaired. He had the greatest drop ball I ever saw. Nobody had its equal.”47

The baseball world, past and contemporary, was also saddened by the pitcher’s passing. Former Boston manager John Morrill stated, “Buffinton was one of the greatest pitchers of his day. … He was very popular with everyone and I am sincerely sorry to hear of his death.”48 Current Boston club owner George B. Dovey and Eastern League Providence club boss Alfred G. Doe jointly conveyed their “terrible shock to hear the sad news. … May God be kind to him. He was a fine fellow; no one better lived than the old champions.”49

Days later, Buffinton’s funeral service was conducted at the First Baptist Church, Fall River, followed by interment at nearby Oak Grove Cemetery. Survivors included the deceased’s widow Anne; his three children; father John; and younger brother Alton. Once renowned, but now long beyond living memory and largely forgotten, Charlie Buffinton was an outstanding nineteenth-century major-league pitcher and a thoroughly decent man.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team..

Sources

Sources for the narrative above include a trove of material provided to the writer by Fall River historian and baseball scholar Philip T. Silvia Jr; US Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, Vol. 1 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 22.

2 Buffinton racked up all of his career wins from the pre-1893 pitcher’s box, located no more than 55½ feet from the batter. He never threw a game from the modern pitching distance of 60 feet 6 inches.

3 In addition to younger brother Moses Alton Buffinton (born 1864), Charlie also had two older stepbrothers, Edward and Ezekiel Morse, the children of mother Phebe’s first marriage. Research has not yet revealed what Charlie’s middle initial, G., stood for.

4 As reflected in the 1880 US Census.

5 Coming slightly after Buffinton’s time in Fall River amateur ranks were cup-of-coffee major leaguers Tom Cahill and Ed O’Neil.

6 Much of the narrative about Buffinton’s amateur playing days is grounded in information generously supplied to the writer by Dr. Philip T. Silvia Jr., Fall River historian and the leading authority on the city’s early baseball teams.

7 As reported locally. See e.g., an account of the Q’s game against the Flint club published in the Fall River (Massachusetts) Herald, September 19, 1879.

8 For more on the subject, see Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1882 League Alliance,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 2, Fall 2019: 105-111.

9 As reported in “Notes and Announcements,” Boston Herald, September 27, 1882: 1, and “Base Ball,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1882: 4.

10 Manager-first baseman John Morrill pitched Boston to an early-season 5-3 win over Philadelphia.

11 As quoted in “One Good Fellow: General Tribute to the Memory of ‘Charley’ Buffinton, Old Ball Player,” reprinted in Philip T. Silvia Jr., ed., Victorian Vistas: Fall River, 1901-1911 (Fall River, Massachusetts: R.E. Smith Print Co., 1992), 527.

12 See e.g., “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 10, 1886: 7. See also, “The King of the Diamond,” New Hampshire Morning Journal & Courier, February 15, 1887: 4.

13 Buffinton’s attendance at the inaugural meeting of the Brotherhood’s executive council was revealed in “Notes,” Sporting Life, November 17, 1886: 1.

14 As reported in “Philadelphia’s New Battery,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 5, 1887: 4; “Buffinton & Gunning Go to Phillies,” Sporting Life, April 6, 1887: 1; “Base Ball,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, April 10, 1887: 3, and elsewhere.

15 See “Buffinton & Gunning,” Boston Herald, April 5, 1887: 8; and “Boston Battery Sold,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, April 6, 1887: 4.

16 Per “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, November 2, 1887: 2.

17 “Local Jottings.” Gunning, then attending medical school during offseasons, signed with the Phillies’ local rival, the American Association Philadelphia Athletics, and remained with the A’s until July 1889. He then returned home to Fall River to commence a long and distinguished career as a doctor.

18 Ferguson contracted typhoid and died in Philadelphia on April 29, 1888.

19 As reported in “Who They Are,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), December 31, 1889: 1; “The Base-Ball Brotherhood,” Baltimore Sun, January 1, 1890: S2; and elsewhere. The nicknames presently assigned to nineteenth-century Philadelphia clubs is a matter of some controversy. For more, see Ed Coen, “Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 2, Fall 2019: 69, 73. See also, Warrington: 117-119.

20 Buffinton and first baseman Sid Farrar reportedly invested $2,500 each into the PL Philadelphia club. See “In Boston Town,” Cleveland Leader, February 8, 1891: 10.

21 See “The Lawyer’s First Move,” New York Tribune, December 15, 1889: 19; “The League in Court,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 15, 1889: 6; and “League vs. Brotherhood,” Erie (Pennsylvania) Times-News, December 16, 1889: 3.

22 As reported in “Players League Pickings,” Boston Herald, September 8, 1890: 5.

23 As reported in “Fogarty Resigns His Captaincy,” New York Tribune, May 15, 1890: 9; “Fogarty Resigns the Captaincy,” Wheeling Register, May 15, 1890: 1; and elsewhere.

24 See e.g., Rain Drops,” Washington Evening Star, May 15, 1890: 9; “Gossip of the Sports,” Washington Critic, May 16, 1890: 4.

25 See again, New York Tribune, May 15, 1890: 9. Fogarty had, in fact, contracted consumption (tuberculosis) and would miss significant playing time during the 1890 season. He died the following May, age 27.

26 See “Pickings and Clippings,” New Haven (Connecticut) Morning Journal & Courier, May 16, 1890: 3.

27 As noted in “Just Watching Things,” Washington Evening Star, October 21, 1890: 8.

28 “Return of President Spalding,” Chicago Tribune, November 22, 1890: 6.

29 See “The Ex-Leaguers Still Hold,” Sporting Life, September 18, 1890: 1.

30 Per “This Morning’s News,” Boston Herald, March 6, 1891: 1.

31 The Boston National League Club (87-51, .630) was also an 1891 pennant-winner.

32 See e.g., “Ward Favors It,” Sporting Life, December 12, 1891: 1; “The Real Solution,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1891: 1.

33 See “The Revolution!” Sporting Life, December 19, 1891: 1: “The War at an End,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1891: 1. See also, David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association — Baseball’s Renegade Major League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 233-235.

34 See “The Players,” Omaha World-Herald, January 2, 1892: 2.

35 See “Outdoor Sports,” Baltimore Sun, March 19, 1892: 4. See also, “Notes of the Diamond,” New York Herald, April 7, 1892: 11; and “Chat of the Diamond,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 1892: 3.

36 Per “Sporting Gossip,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, April 25, 1892: 5.

37 According to “Scraps of Sport,” St. Paul Globe, June 26, 1892: 10.

38 With a home game attendance of 93,589, Baltimore drew the fewest fans of any of the 12 clubs in the 1892 National League.

39 As reported in “Buffinton Released,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1892: 7; “Holding Their Own,” Washington Evening Star, July 1, 1892: 7; and elsewhere.

40 In his profile of our subject, nineteenth-century baseball historian David Nemec asserts that Buffinton was thereafter “informally blacklisted because of the circumstances of his release.” Major League Baseball Profiles, 23.

41 Even when relief pitchers are excluded, there are still 16 Hall of Fame pitchers with fewer wins than Buffinton. For more on the Hall of Fame worthiness of Buffinton and other neglected nineteenth-century standouts, see C.C. Johnson Spink, “We believe …,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1977: 14.

42 Father John Buffinton was the company’s business agent and younger brother Alton its treasurer. Charlie was also an investor/stockholder in Bowenville Coal.

43 See e.g., “The National Game,” Elizabeth City (North Carolina) Fisherman & Farmer, August 12, 1892: 7. See also, Major League Baseball Profiles, 23.

44 As revealed in “Buffinton’s Fame Was Country Wide,” Fall River Herald, September 25, 1907.

45 Per “‘Charlie’ Buffinton, Coal Dealer and Former Ball Player, Dead,” Fall River Herald, September 24, 1907.

46 According to the Buffinton death certificate. A Boston heart specialist subsequently opined that Buffinton suffered from what was “commonly known as ‘athletic heart,’ … [a condition] quite frequently found among men who devoted themselves in youth or early manhood to severe physical exercise.” Fall River Herald, September 25, 1905, quoting Dr. Frederick C. Shattuck who had assisted at the Buffinton autopsy.

47 Per “Buffinton’s Fame Was Country Wide.”

48 Quoted in “One Good Fellow: General Tribute to Memory of ‘Charley’ Buffinton, Old Ball Player,” Fall River Herald, September 24, 1907.

49 Quoted in “One Good Fellow.”

Full Name

Charles G. Buffinton

Born

June 14, 1861 at Fall River, MA (USA)

Died

September 23, 1907 at Fall River, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.