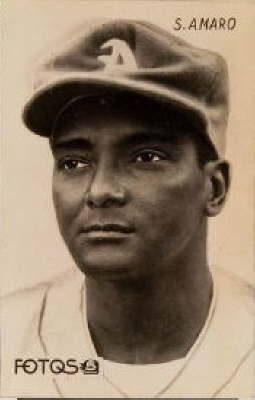

Santos Amaro

In December 2020, the Negro Leagues were recognized as major leagues. The Amaro family might thus have retroactively become the first to send three generations of players to the top level,1 ahead of the Boones, the Bells, the Hairstons, and the Colemans.2 Their worthy heritage started with their big Cuban patriarch, Santos Amaro, who had a long and distinguished career, primarily in Cuba and Mexico. As a man of color born in 1908, he was prevented by racial barriers from playing in the American or National League during his prime. He also made the personal choice not to play in the Negro Leagues because of the racism he encountered in the United States.

In December 2020, the Negro Leagues were recognized as major leagues. The Amaro family might thus have retroactively become the first to send three generations of players to the top level,1 ahead of the Boones, the Bells, the Hairstons, and the Colemans.2 Their worthy heritage started with their big Cuban patriarch, Santos Amaro, who had a long and distinguished career, primarily in Cuba and Mexico. As a man of color born in 1908, he was prevented by racial barriers from playing in the American or National League during his prime. He also made the personal choice not to play in the Negro Leagues because of the racism he encountered in the United States.

Nonetheless, Santos had the talent. His son and grandson – Rubén Amaro Sr. and Ruben Jr. – were in the majors for 11 and eight years, respectively. Two members of the clan’s fourth generation were chosen in the amateur draft before going to the college ranks. “Baseball is our way of life in the Amaro family,” said Rubén Sr.3

Santos Amaro played 14 winter seasons in his homeland from 1936-37 to 1949-50. He was in Mexico during the summers from the late 1920s through 1955, including at least 17 seasons in the Mexican League. He was also a manager in both Cuba and his adopted home, and he eventually became a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame in each nation.

Originally a catcher, Amaro also played third base, first base, and across the outfield – but his true home as a player was in right field, thanks to his powerful throwing arm.4 Fermín “Mike” Guerra, a catcher for many years in Cuba and the majors, told Cuban baseball historian Roberto González Echevarría that Amaro’s arm was the strongest he had ever seen in an outfielder.5 Amaro consistently hit around .300, though he hit mainly line drives and had surprisingly little home-run power for his size. “He never lifted the ball,” said Rubén Sr., “but he was a strong gap hitter who used all fields, got lots of extra bases, and was very conscientious with men in scoring position.”6

Amaro was a man of regal appearance and bearing. The Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame described him as “a complete gentleman outside the diamond, but on the field of play he practiced aggressive baseball, because he did not like to lose; he always wanted to be a winner and always gave his maximum effort to achieve this.”7 He was a member of eight champion teams in Cuba plus at least five more in Mexico – three confirmed as player, one more as player-manager, and another as manager alone. Author Milton Jamail put Amaro in a special category along with three other men he had the good fortune to interview: Curt Flood, Vic Power, and Willie Wells. “All fought the discrimination they faced through the quality of their play on the field and their incredible strength and dignity off it.”8 These attributes served Amaro well as a manager. He also passed them on to his family.

Santos Amaro Oliva was born on March 14, 1908, in Aguacate. This place – its name means avocado in Spanish – is a village in the former province of La Habana.9 It is in the western part of the country, between the Cuban capital and the city of Matanzas. When Santos was a youth, it had between 2,000 and 3,000 inhabitants. As was true of much of Cuba, the area was agricultural. “My grandmother’s family cultivated rice, mainly,” said Rubén Sr.10

Santos Amaro shared his given name with his father, a merchant seaman who came from Portugal. Baseball’s influence was already visible in the family. Author Nick Wilson wrote, “He was following in the footsteps of his father, who played at the turn of the century. When I interviewed Santos at the age of 92, he could not remember whether his father had confined himself to pitching or had played many positions as was customary in those early days.” Wilson added, “But there were many things about his own career which he could recall with clarity.”11 Though Amaro died not long after Wilson spoke to him, Rubén Sr.’s own excellent memory strongly complements what can be gathered from other sources.

Amaro’s mother, Regla Oliva, was (according to Rubén Sr.) “always a homemaker, a great cook, very able – doing everything to raise cattle and children when very young. She died in her sleep in Cuba when she was 114 years old, very healthy. I had just talked to her on the phone four days before she passed away. Abuelita Regla always mentioned that she was born in Cuba, but her parents both were Abencerraje Moors from Africa – nomads. They were slaves brought to Cuba and were given their freedom there, got married, and had three children.”12

Santos was the fourth of five children. He had three older brothers, named Mario, Rogelio, and Elpidio; he was followed by a sister named Visitación (“Niña”). “The family moved from Madruga, a bigger town near Aguacate, to Luyanó/Reparto Rocafort [neighborhoods in the city of Havana] when my father was 13 years old,” said Rubén Sr. “The oldest brothers, Mario and Rogelio, started work to support the family. My grandfather had passed away.”13

Santos became an apprentice carpenter, learning the craft of cabinetmaking and detail work.14 “He played baseball in the placeres, or sandlots, when young,” remembered Rubén Sr. “He was always a catcher – too skinny and too tall, but a great arm. His best friend growing up was Kid Chocolate, one of the greatest boxers of Cuba – very small, totally opposite.”15

With a group of other young Cubans, Santos went to Mexico in 1928 with his first professional team, a traveling outfit called Bacardí. Three teammates also went on to play many years in Mexico: pitcher Alcibíades Palma, catcher Rafael “Sungo” Pedrozo, and shortstop Marcelino Bauza. The manager was a stocky little man named Luis Sansirena; he too spent decades in Mexico as a manager and coach. Amaro earned $10 a week, plus room and board.16

In 1929 Amaro met a young woman named Josefina Mora (1910-2007), a member of the Vera Cruz Women’s Professional Baseball Club.17 They were married in 1930 in Veracruz – “by a justice of the peace,” Rubén Sr. remembered. “They had a Catholic Church wedding in the Cathedral of Veracruz in 1951. It was my 15th birthday gift.”18 Santos and “Doña Pepa” had two sons. Mario was born in 1931 in Veracruz; Rubén was born in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico in 1936.19 Around 1956, with both of their sons grown men, the couple adopted a seven-month-old baby girl named Ana Teresa, fondly known as “Ana Banana.”

As Rubén Sr. told author Stuart Gustafson many years later, his parents were a study in contrasts. Santos was tall (1.92 meters, or roughly 6-feet-3½) with dark coffee-colored skin. As an adult, he filled out to 95 kilos (210 pounds).20 Josefina was petite (5-feet-1) and fair (her grandparents on both sides were Spanish). Rubén and Mario wound up in between at 5-feet-10½. Doña Pepa was the one with whom the boys practiced their baseball skills, because Santos stressed education above all.21 “He only had an elementary education,” said Rubén Sr. in 2010, “but he told me baseball players have a lot of empty time. He used to read all the time and played with words. When we were doing our homework, he’d come by and say, ‘Fix that. That’s not done properly.’ There would be no playing baseball until we were ready to face the world otherwise. He would preach to us every day. ‘Get prepared. And when you embark on a task, don’t look back.’ ”22

This gentle but firm fatherly guidance continued when Rubén Sr. was in his early years in the minor leagues. Amaro spent the summers of 1956 and 1957 with Houston. Over half a century later, he recalled that he was ready to quit because of the racial and ethnic taunts of some Texas League fans – “the vituperation,” in his own words. Jim Crow laws were also humiliating. But he stuck with it after Santos Amaro calmly reminded his son that he had originally let him leave school on the condition that he do whatever it took to reach the majors.23

Mario Amaro was a skillful baseball player too, but he chose instead to focus on medicine (he also played professional soccer in Cuba while in medical school).24 In 1965, Rubén Sr. said, “No professional sport is as highly regarded in Mexico as it is in the US. A doctor, a lawyer, an engineer has more respect than any baseball player. I have a brother here who is a doctor, and everywhere we go people say, ‘This is Ruben Amaro’s brother.’ But back home, when people see me, they say, ‘Ah, there goes Dr. Amaro’s brother.’ ”25

Mario Amaro was a skillful baseball player too, but he chose instead to focus on medicine (he also played professional soccer in Cuba while in medical school).24 In 1965, Rubén Sr. said, “No professional sport is as highly regarded in Mexico as it is in the US. A doctor, a lawyer, an engineer has more respect than any baseball player. I have a brother here who is a doctor, and everywhere we go people say, ‘This is Ruben Amaro’s brother.’ But back home, when people see me, they say, ‘Ah, there goes Dr. Amaro’s brother.’ ”25

Another intriguing insight into Santos Amaro the autodidact came from another great Cuban player, Hall of Famer Martín Dihigo. El Inmortal was born two years before Amaro and they played against each other in Cuba in the 1920s. Dihigo later became a teammate in other nations, godfather to Rubén Sr. – and a fellow member of the Freemasons.26 A 1938 letter from Dihigo is visible on the website of the auction firm Leland’s. In it, he described his efforts to absorb the knowledge contained in a three-volume Masonic encyclopedia.27 Amaro must have done the same – “he was a Past Master later on in his life,” said Rubén Sr.28

After barnstorming almost two years with Bacardí, Amaro joined the Mexican League team Tigres de Comintra in 1930, according to Rubén Sr. This team won the league championship. Unfortunately, further documentation has not yet surfaced; La Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano’s records start in 1937.

Though his features did not fit the “African” stereotype, Amaro’s complexion meant that he encountered racism while playing with a barnstorming team in the United States in 1932. By one account, he did not wish to return.29 “But in 1935, he went on an eighty-game, fourteen-state tour of the United States with … La Junta de Nuevo Laredo.”30 He received some press in the U.S.; for example, the Wisconsin State Journal noted Amaro as the “star catcher of the Junta baseball team” and “long dusky rightfielder.” It also referred to him as “the Babe Ruth of the Mexican outfit” even though he was a line-drive hitter.31

Santos was not allowed to play much while the tour was in Texas. The prejudice he faced in the U.S. apparently killed his desire to play in the Negro Leagues. Yet Afro-Cubans faced bias even at home – in baseball and in society at large. Cuba’s high-level Amateur League, which exceeded pro ball in popularity for much of the first half of the 20th century, remained segregated until 1959. Two integrated amateur leagues eventually sprang up in Cuba, but not until the 1940s. Mexico was a more welcoming environment. In addition to greater opportunities on the field, several black Cuban players married Mexican women. One was Pedro Orta, whose son Jorge became a major leaguer from 1972 to 1987.32

Despite his limited action in the Lone Star State, Amaro still made an impression on Texan fans who saw him in Nuevo Laredo. In 1965 a man from the border city of McAllen named Bill Walsh wrote a letter to Sports Illustrated to that effect. It read in part, “In his prime Santos Amaro could have played on any ball club anywhere in the world. There was one reason he did not: he was black. Other Cubans had played in the majors, but they were always light in color. Santos could perform at any spot on the baseball field, except as a pitcher. In 1936 I saw him in a four-game series against an American League All-Star team headed by Rogers Hornsby, and including such players as Pinky Higgins, Red Kress, Eric McNair, and pitchers such as Ted Lyons and Jack Knott. In this series at Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, Santos played in the outfield, and in the four games he got 13 hits.”

Walsh continued, “But it was as a catcher that Santos was at his best. I have seen [Gabby] Hartnett, [Yogi] Berra and [Bill] Dickey, and none of them was any better than Santos Amaro. You cannot say anything about a baseball catcher better than that.”33 Mexican sources suggest that Amaro’s height hindered him behind the plate and was a factor in his position switch.34 Perhaps his athleticism was better suited to other spots, though – Amaro’s size and leaping ability won him the nickname El Canguro – “The Kangaroo.”35 By another account, though, it came in the 1930s as he was running to try to catch a team bus that had left him behind at a restaurant.36 Amaro’s contemporary, pitcher Conrado Marrero, cited skin color as well as stature.37

In 1937 Amaro went to play in the Dominican Republic. That was a remarkable year for Dominican baseball; the season was dedicated to the re-election of dictator Rafael Trujillo, and Ciudad Trujillo assembled a powerhouse team, luring the best Negro Leaguers of the day to come down. The league’s other teams competed, at least to a degree. Águilas Cibaeñas of Santiago signed Amaro plus Martín Dihigo and another fellow Cuban, Luis E. Tiant. With all the foreign reinforcements, there were relatively few Dominicans in the league, but the Santiago club had one of the nation’s early stars, Horacio “Rabbit” Martínez (Juan “Tetelo” Vargas was with Ciudad Trujillo). Amaro displayed power that was unusual for him; he tied Dihigo for the league lead in homers with four.38

The Dominican pro circuit collapsed after the excesses of 1937, however, not to reappear for another 14 years. Amaro then went to Venezuela in the summer of 1938, as did various other Latino ballplayers. A book called Historia del Béisbol en el Zulia, which focuses on the game in Venezuela’s westernmost state, notes that he joined the Centauros team.39 This locale remained important to the Amaro family over the years. Rubén Sr. became a manager and executive for the winter-ball team Águilas del Zulia, and Rubén Jr. played with that club for six seasons.

Rubén Sr. said that Santos “started to play in Venezuela with the Centauros, but didn’t have any success and they sent him to the other pro league, the Central League, with the Valdés club. He won the batting title. The other teams were Venezuela, Premier, Vencedor, and Vargas.”40 It was a brief schedule, though; Venezuelan baseball historian José Antero Núñez showed that Amaro was 13 for 31 (.419). He appeared in nine of the club’s 15 games.41

Rubén Sr. said that Santos “started to play in Venezuela with the Centauros, but didn’t have any success and they sent him to the other pro league, the Central League, with the Valdés club. He won the batting title. The other teams were Venezuela, Premier, Vencedor, and Vargas.”40 It was a brief schedule, though; Venezuelan baseball historian José Antero Núñez showed that Amaro was 13 for 31 (.419). He appeared in nine of the club’s 15 games.41

According to Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961, Amaro’s first Cuban winter team was Santa Clara. He was there for five seasons, starting in 1936-37. (The Great Depression hit Cuban baseball hard in the early 1930s; the 1933-34 season was canceled.) In his second year, the Leopardos won the league championship with a lineup that also starred Negro Leaguer Sam Bankhead, who won the Cuban batting title. The staff ace was US Hall of Famer Ray “Jabao” Brown. The 1938-39 squad – featuring the great Josh Gibson as well as Brown – repeated as champs. “My father’s time in Santa Clara was his favorite,” said Rubén Sr. “It was a prelude to arriving at the top of his game around great players.”42

The first available Mexican League records for “Santicos” Amaro (as he was also known) come from 1939, when he was 31 years old. He joined Águila de Veracruz. In 1940 Águila was not in the league; Amaro played 14 games for the Veracruz Azules (Blues). This team was the league champion, which was not surprising – it was loaded with several of the all-time great Negro Leaguers: Josh Gibson, Willie Wells, Leon Day, Ray Dandridge, and Cool Papa Bell, as well as Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe. Martín Dihigo was also with the club as player-manager. Mexican magnate Jorge Pasquel had bought the club before the season, moved it to Mexico City, and persuaded Dihigo to come aboard.43

“He always mentioned the superb experience of playing against and besides players of that caliber,” said Rubén Sr., “but two players that he considered above everyone else of that era were Martín Dihigo and Alejandro Oms, both from Cuba. His favorite players from the USA were in this order: James Bell (Cool Papa), Buck Leonard, Raymond Dandridge, Roy Campanella, and Josh Gibson.

“Pitchers: Dihigo, Satch Paige, Max Lanier, Ramón Bragaña, Lázaro Salazar, Vidal López (Venezuela), Connie Marrero, Tomás de la Cruz, Theolic Smith, Sal Maglie, Sandalio Consuegra, Agapito Mayor, Indian Torres. Whenever my father talked to his peers about their times, those names were always at the top of his conversations.”44

After his year with the Azules, Amaro then played seven-plus seasons with the Tampico Alijadores45 from 1941. Tampico was one of the better teams in Mexico during the 1940s, winning back-to-back championships in 1945 and 1946 under manager Armando Marsáns, one of the early Cubans to play in the majors. Amaro also gained his first experience as a manager in Tampico. He led the Alijadores for part of the 1943 season (replacing Willie Wells) and part of 1947 (taking over for Marsáns). “I remember the days in Tampico. We lived there more than five years,” said Rubén Sr. “When Tampico left the Mexican League [the club folded partway through the 1948 season], he went back to the Azules.”46

As of the 1941-42 Cuban winter season, Amaro was with the Almendares Alacranes. That team was the league champion, and so were the Scorpions of 1942-43, 1944-45, and 1946-47. During this time, Amaro also appeared in the American Series of 1942, when the Brooklyn Dodgers came to Havana for spring training and lost three out of five games to a Cuban all-star team.

In 1947-48, Cuba had an “alternative” league called La Liga Nacional (or Players Federation). The circuit, which lasted just one year, featured players who had become “outlaws” in the US because of their association with the Mexican League in 1946. Amaro played first with Alacranes, and then he went to the club called Cuba in a trade that also involved Sal Maglie. Amaro took over as manager for Cuba, succeeding Napoleón Reyes, who “retired on doctor’s orders. The combined work of player and manager brought a breakdown.”47

Amaro then rejoined Almendares in 1948-49, playing his last two winters at home for the Scorpions. Both of these teams became league champions and thus went on to play in the first and second Caribbean Series. Though mostly Cuban, there were notable Americans, such as future TV star Chuck Connors and Al Gionfriddo. In fact, Amaro was signed to replace Connors in January 1950 – allegedly after manager Fermín Guerra released the Dodgers farmhand “for failing to respect training rules.”48 It is remarkable to note that one man from the 1949-50 roster still survived as of 2012: Conrado Marrero, at 101 the oldest living major leaguer. (Catcher Andrés Fleitas died in December 2011 at the age of 95.)

Amaro ranked sixth in the history of Cuba’s main professional league in hits (725) and ninth in RBIs (321). He batted over .300 five times in his career there, finishing with a lifetime average of .294 – though he had just 12 homers. (Total games played are not available.) He wasn’t quite through as a player at home, though – in 1950-51, another new league sprang up, again called La Liga Nacional. Background on this league is available in Roberto González Echevarría’s book The Pride of Havana.49 Peter Bjarkman, historian of Cuban baseball, summed it up as follows:

“By that time, the ban had been lifted on [all] former Mexican leaguers, but the overall labor dispute had reduced the number of jobs in the Cuban League for older native Cuban players. With the assistance of Martín Dihigo, some of the over-the-hill veterans organized a separate league in Havana which was considered a minor circuit, not a rival to the normal Cuban League, and drew little attention. Amaro played in that league and did manage the club called Fé (the teams were all named after historic teams from the pre-1920s Cuban League).”50

Rubén Amaro, Sr.’s memory tallies with the historians’ description. “My father was active with Almendares until 1950. In 1951 there was an experiment to see if Cuba could support two professional leagues, the other one playing at the old Tropical Stadium. My father managed the team La Fé; lots of young Cuban players that couldn’t make the big season. Four teams formed the league. The people didn’t support that league, they had a much better show in El Cerro Stadium, better than the big leagues. The best black players, the best white players from the big leagues and the best Cuban players at the time, all in one ballpark distributed in four teams.”51

Over in Mexico, Amaro came back to Águila in 1949 and spent his remaining seven summers as a player at home in Veracruz. The Amaro family traveled between Mexico and Cuba until settling permanently in Mexico in 1951. “My father was finished as a player in Cuba,” said Rubén Sr., “but he was going to continue to play in the Mexican League with the Veracruz team in the summer, as well as managing in the Central Veracruz League in the winter.”52

Santos was always a Cuban at heart, though. As Rubén Sr. said, “Both Pipo and Mima [as the Amaro sons called their parents] traveled several times to see their sons and grandchildren. My father never gave up his Cuban citizenship. We all tried to make him Mexican. It was easier for him to travel anywhere with a Mexican passport.”53 Yet it’s worth noting that Amaro liked to remind everyone about the historical significance of the first Mexican-born major leaguer, Baldomero “Mel” Almada.54

Amaro succeeded Martín Dihigo as manager of Águila in 1951 and led the club to the Mexican League championship in 1952. Though well into his 40s by that time, Amaro still played on occasion. His last five games as an active player took place in 1955. Over his documented summer career in Mexico, he hit .314 with 32 homers and 705 RBIs in 1,186 games.

Amaro had also stayed active as a player in Mexican winter ball. His team was the Orizaba Cerveceros, or Brewers – this city had long been known as “the Mexican Milwaukee.”55 He was manager only in 1951-52, but he had a fine season as player-manager in 1952-53, when the circuit went from four to six teams and became known as the Veracruz Winter League. He batted .360 (45 for 125).56 As Cuban sportswriter Fausto Miranda later remembered, Amaro liked to say, “It’s not age, it’s the shape you can stay in.”57

Dihigo returned to the helm for Águila partway through the 1956 season, and Amaro remained with the team as a coach.58 Santos managed part of the 1959 season for the Mexico City Tigres, but was replaced at the beginning of June after the club got off to a dreadful start.59 He came back to Águila as third-base coach,60 and became manager once again in 1960. He spent four more summers as skipper in his home city, winning another league championship in 1961.

In the winter of 1962-63, Amaro managed Jalapa of the Veracruz League, a team that included his son Rubén. But when the governor of Veracruz state withdrew financial support for the Jalapa franchise, it folded, and the league’s three other teams followed suit.61 The following winter, Amaro set off to manage in another nation: Nicaragua.62 His stay with the Oriental team was brief, though; he stepped down during the Christmas holidays.63 Even Rubén Sr. couldn’t add anything about that chapter of his career.

Amaro started the 1964 summer season with León of the Mexican Center League, a lower-level circuit. He was replaced as manager by Dan Bankhead, the former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher. Back in the ’30s, Dan’s older brother Sam had been Amaro’s teammate with Santa Clara and an opponent with Ciudad Trujillo. Amaro also managed Reynosa in the Mexican League that summer. The following year, 1965, was his last as a skipper. He managed Aguascalientes in the Mexican Center League for part of the season.

“I believe Pipo finished his career in baseball after the 1965 Aguascalientes job,” said Rubén Sr. “He started work with Rubio Exsome, a construction engineering firm in Veracruz, after that.” Amaro also worked for Deportivo Veracruzano, the city’s foremost sporting institution. His second career continued for 22 years.64

Santos and Pepa Amaro continued to live in their Veracruz home until late 1997. They stayed for a couple of months with a niece, but Rubén Sr. said, “In February 1998, my brother Mario and I decided to put both Mima and Pipo in the nursing home Residencias La Paz under Spanish nuns. Mima suffered a fall trying to clean windows at her house, broke her hip, recuperated very well and we didn’t want them to have any more mishaps. One of the rules of La Paz was that anyone joining them must be able to take care of themselves. If later on they were unable to do that, they could stay. Mima and Pipo continued to travel and visit their family anytime.

“Both lived there until the Lord took them away. Pipo, May 31, 2001, and Mima, March 16, 2007. They were both cremated and their ashes remain together in Veracruz. Dad passed away of natural causes, all the nuns praying and singing around him. Mima fell in her bathroom early one morning, didn’t call for help, broke her femur in two places and left us after three days from the day she fell.”65

Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso, who played for Amaro early in his career, told Nick Wilson, “[Amaro] was a very kind and gentle man. He never hurt anyone.” A Cuban champion boxer, Ultiminio “Sugar” Ramos, knew Amaro because he fought out of Mexico after Fidel Castro came to power. Ramos told Wilson, “He attracted people and liked to engage them. He was a guy who liked to have a good time.” Beyond that, Ramos said, “He brought a great glory to us because he was such a great baseball player.66 The Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame (in exile) inducted Santos Amaro in 1967. He became a member of the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977. In 2012 he was named part of the fourth class of veterans to join the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame in the Dominican Republic.

In November 2012, 101-year-old Conrado Marrero contributed his opinion of his teammate from six decades past. “Santos Amaro was a serious, decent, and honorable man … one heck of a ballplayer from his cap to his spikes.”67

This biography was riginally published in 2012. An updated version appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin. Subsequently, it was further updated on January 7, 2023, to reflect Santos Amaro’s recognition as a major-leaguer.

Sources

Grateful acknowledgment to Rubén Amaro Sr. for his memories (telephone interview, October 18, 2012, and a series of e-mails from October 31 through November 25, 2012).

Continued thanks to Rogelio Marrero for obtaining the input of his grandfather, Conrado Marrero.

Continued thanks to Jesús Alberto Rubio in Mexico for various details of Santos Amaro’s career. Jesús knew Amaro personally when he lived in Veracruz in the 1970s and early 1980s. He devoted the March 14, 2010, edition of his column “Al Bat” to Amaro.

Pedro Treto Cisneros, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition, 2011).

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2003).

Nick Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005).

Photo Credits

Courtesy of Jesús Alberto Rubio collection.

Notes

1 If one counts indirect lineage, then the Schofield/Werth family could also be included.

2 Ruben Amaro, Jr. made it to the majors more than a year ahead of Bret Boone.

3 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Rubén Amaro, Sr., October 18, 2012.

4 “Santos ‘Canguro’ Amaro,” Amaro’s page on Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame website (http://www.salondelafama.com.mx/salondelafama/trono/alfasf.asp?x=36). This appears to be a synopsis of stories by Jesús Alberto Rubio.

5 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 261.

6 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 13, 2012.

7 “Santos ‘Canguro’ Amaro”

8 Milton Jamail, Venezuelan Bust, Baseball Boom (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 243.

9 In 1976 Cuba’s original six provinces were subdivided. La Habana was split in two, and Aguacate is today in the province of Mayabeque.

10 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 13, 2012.

11 Nick Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005), 139.

12 E-mails from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 13 and November 25, 2012.

13 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16, 2012.

14 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 13, 2012.

15 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 15, 2012.

16 “Santos ‘Canguro’ Amaro.”

17 Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States, 139.

18 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 15, 2012.

19 Other sources have shown different spots in Mexico as Rubén Amaro Mora’s birthplace, but Nuevo Laredo – as confirmed by Rubén Sr. in October 2012 – fits with that point in his father’s career.

20 José Antero Núñez, Héctor Benítez, Redondo (Caracas, Venezuela: publisher unknown, 2004), 36.

21 Stuart Gustafson, Remembering Our Parents … Stories and Sayings from Mom & Dad, Excerpt from book to be released, on Gustafson’s Legacydoctor.com site (http://legacydoctor.com/?page_id=376).

22 Paul Hagen, “Father’s Day: Ruben Amaro Sr. and Jr.,” Phillynews.com, June 16, 2010.

23 Jorge Aranguré, Jr., “Ruben Amaro Jr. a confident leader,” ESPN The Magazine, October 3, 2011. Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Rubén Amaro, Sr., October 18, 2012.

24 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 15, 2012. First cousin Mario Amaro Romay, a right-handed pitcher, appeared in two games for Veracruz in 1955 and in the US minors for Mexicali in 1955 (where Rubén Sr. was his teammate) and 1956.

25 Robert H. Boyle, “The Latins Storm Las Grandes Ligas,” Sports Illustrated, August 9, 1965.

26 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Rubén Amaro, Sr., October 18, 2012.

27 http://www.lelands.com/Auction/AuctionDetail/24206/June-2005/Sports/Baseball-Memorabilia/Lot366~Martin-Dihigo-Letter

28 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 15, 2012.

29 Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States, 139.

30 Milton Jamail, “Baseball in Southern Culture, American Culture, and the Caribbean.” Part of Douglass Sullivan-González and Charles Reagan Wilson, editors, The South and Caribbean (Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 160.

31 Wisconsin State Journal, (Madison, Wisconsin) June 18 and June 22, 1935.

32 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 22.

33 “19th Hole: The Readers Take Over,” Sports Illustrated, April 5, 1965.

34 “Santos ‘Canguro’ Amaro.”

35 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 260.

36 Milton Jamail, “Baseball in Southern Culture, American Culture, and the Caribbean,” Part of Douglass Sullivan-González and Charles Reagan Wilson, editors, The South and Caribbean (Oxford, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 160.

37 E-mail from Rogelio Marrero to Rory Costello, November 21, 2012.

38 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season (Jefferson City, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007), 146.

39 Luis Verde, Historia del Béisbol en el Zulia (Maracaibo, Venezuela: Editorial Maracaibo, S.R.L., 1999).

40 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 15, 2012.

41 Antero Núñez, Héctor Benítez, Redondo, 44.

42 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16, 2012.

43 Rob Ruck, Raceball (Boston: Beacon Press, 2012), 68.

44 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16, 2012.

45 The word alijador in Spanish has various meanings, but in the baseball context, Alijadores is often translated as Lightermen. A lighter is a type of barge, and Tampico is a port city. Lightermen transferred goods between ships and docks.

46 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16, 2012.

47 Pedro Galiana, “Results of O.B. Pact Hailed by Cuban League,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1948, 20.

48 Lou Hernández, The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues, 1947-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2001), 112. However, The Sporting News indicated in its issue of February 8, 1950, that Connors’ season was cut short by an ailing foot.

49 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 312-313.

50 E-mail from Peter C. Bjarkman to Rory Costello, November 13, 2012. Bjarkman added, “The league was of such little stature that Jorge Figueredo does not list any of the stats in his Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 and I did not mention it in my own A History of Cuban Baseball.”

51 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16, 2012.

52 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16, 2012.

53 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, October 31, 2012.

54 Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States, 131.

55 Gulian Lansing Morrill, The Devil in Mexico (Minneapolis: self-published, 1917), 274.

56 The Sporting News, March 4, 1953.

57 Fausto Miranda, “Peloteros Viejos de Verdad,” El Nuevo Herald (Miami, Florida), October 4, 1992, 1C.

58 Miguel A. Calzadilla, “Veracruz Halted after 10 Straight,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1956, 35.

59 Roberto Hernandez, “Shakeup Mapped for Tail-End Club,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1959, 50.

60 “Bejerano to Pilot Stars,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1959, 46.

61 Roberto Hernández, “[Julio] Becquer, Arano Standouts as Veracruz League Opens,” The Sporting News, November 17, 1962, 29. Roberto Hernández, “Jalapa Gives Up Franchise; Veracruz League Goes Under,” The Sporting News, January 5, 1963, 37.

63 Horacio Ruiz, “Oriental Turns on Steam with Friol as Pilot,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1964, 23.

64 E-mails from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 16 and November 17, 2012.

65 E-mail from Rubén Amaro, Sr. to Rory Costello, November 17, 2012.

66 Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States, 139-140.

67 E-mail from Rogelio Marrero to Rory Costello, November 21, 2012.

Full Name

Santos Amaro Oliva

Born

March 14, 1908 at Aguacate, La Habana (CU)

Died

May 31, 2001 at Veracruz, Veracruz (MX)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.