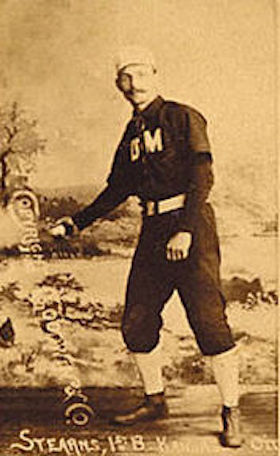

Dan Stearns

When he was 18 years old he was playing major-league baseball in his hometown of Buffalo, New York. Twenty-two years later he was playing baseball in an obscure minor league in a small town in far-away South Dakota. In between those times Dan Stearns had shuffled back and forth between the major leagues and the minors. At this point he had spent over half of his life as a professional baseball player. Never a star himself, Stearns had played for and against some of the greatest stars of the century.

When he was 18 years old he was playing major-league baseball in his hometown of Buffalo, New York. Twenty-two years later he was playing baseball in an obscure minor league in a small town in far-away South Dakota. In between those times Dan Stearns had shuffled back and forth between the major leagues and the minors. At this point he had spent over half of his life as a professional baseball player. Never a star himself, Stearns had played for and against some of the greatest stars of the century.

Daniel Eckford Stearns was born October 17, 1861, in Buffalo, New York, eldest of the six children of Ellen Murphy and Henry Stearns, a policeman. His mother was born in Ireland, while his father was a native New Yorker.

In the spring of 1880, 18-year-old Dan, who had completed seven grades of elementary school, was working in an agricultural implement shop in Buffalo, and very likely playing amateur or semipro baseball. Before the summer was over he had become a professional baseball player. With no minor-league experience, he made his major-league debut for his hometown Buffalo Bisons, then a member of the National League, on August 17, 1880. He became the first person born during the Civil War to become a major leaguer.

Although his family called him Dan, baseball sources used the names Dan and Ecky interchangeably. Ecky, of course, was short for his middle name, Eckford. No relationship to the famous Eckfords of Brooklyn has been established. At a time when the average major leaguer was under six feet in height, the sturdily-built Stearns was an impressive figure at six-feet-one and 185 pounds. He batted left-handed and threw with his right. For Buffalo he played mainly in the outfield, although he got into a few games at third base, shortstop, and catcher. He did not field particularly well at any position and hit a miserable .183. Under the limited reserve clause in effect at the time, each club was able to protect five players. Given his mediocre start, it is no surprise that Buffalo did not put Stearns on its reserve list.

Stearns was out of organized baseball during most of the 1881 season, but he did manage to get into three games at shortstop for the new Detroit club that replaced Cincinnati in the National League. He got his big break in 1882 when the American Association, the so-called Beer and Whiskey League, was formed. The Cincinnati Red Stockings of the new circuit selected him and played him mainly at first base, the position for which he seemed best suited. That season the American Association stipulated that player uniforms be differentiated according to the position played. Stearns was a striking figure in his knee-length red stockings, white trousers, and red and white striped shirt. Whether the colorful uniforms were viewed as cute or gaudy depended on the eye of the beholder. Someone said Stearns looked like a giant stick of peppermint candy.

On one day, September 11, 1882, Stearns unwillingly helped a rival gain a measure of baseball immortality. Tony “Count” Mullane of the Louisville Eclipse carried a no-hitter into the ninth inning of a game against the Red Stockings. With two outs in the final frame, Pop Snyder of Cincinnati hit a fly ball to center field that should have been an easy out, but John Reccius mishandled it for an error, and Snyder reached first base safely. Snyder complained to the umpire that Mullane was illegally bringing his arm above his shoulder while pitching, but the umpire rejected the objection. Mullane’s no-hitter was still intact; he needed one more out, and Ecky Stearns was at the plate. With a chance to spoil the Count’s no-no bid, Stearns grounded out to end the game and Tony Mullane had pitched the first no-hitter in the history of the American Association.

In the eighth inning of that game, Stearns had played a minor role in events that hurt the reputation of one of the game’s greatest stars, Pete Browning. Under the rules in effect in the American Association in 1882, a substitute was permitted to run for an injured player, provided the captains of both squads agreed. The pinch-runner was to stand behind home plate, ready to run if the batter made contact. Browning, who had pulled a leg muscle, cam to the plate, and Guy Hecker, the approved substitute runner, stepped behind the batter’s box, ready to run if Browning hit the ball. And Browning did hit the ball, lining it into the outfield. Forgetting the presence of the substitute runner, Browning took off for first base. The surprised Hecker stopped in his tracks, not knowing what to do. When the ball was returned to the infield, pitcher Will White threw it to Stearns at first base. The umpire called an out as the correct runner, Hecker, had not reached base.

Browning’s boner provided fuel for those who believed that his senses had been dulled by overindulgence in alcohol. The incident also cost the Louisville slugger a place in the record books. If the correct runner had reached first base, Browning would have completed his American Association career with a .342 batting average, tied with Dan Brouthers for the highest career average in the circuit’s history. As it was, his .341 was only second-best.

The Red Stockings were not pleased with Stearns’s performance at first base. His .931 fielding average was 41 points lower than the league leader and 26 points lower than the lowest of the circuit’s other regular first basemen.1 But they had no choice but to turn the position over to Stearns. Their only other first sacker, Henry Luff, left the club in midstream. Baseball historian Lee Allen wrote that Luff quit in a huff over a matter of a five dollar fine levied by the Reds for making a one-handed catch.2

Despite hitting a respectable .257 and helping the Red Stockings win the pennant, Stearns was deemed expendable. A dispute between the Reds and the New York Metropolitans over the services of first baseman Long John Reilly was resolved in favor of Cincinnati. Stearns was let go. He signed with Baltimore and became the regular first baseman for the Orioles, leading the league in both assists and errors in 1883 and 1884. During the 1885 season Stearns returned briefly to his old team, the Buffalo Bisons, but he couldn’t hit National league pitching. It appeared that his major-league career was over at the age of 23, but it wasn’t. After several years in the minors, he made it back to the majors and had a good year with the Kansas City Cowboys of the American Association. He played his last major-league game for the Cowboys on October 14, 1889, at the age of 27. Unfortunately, Kansas City left the league at the end of the season, and it was back to the minors for Ecky Stearns.

In 1886 Stearns had his first minor-league experience. It turned out to be quite an experience. During the remaining years of his professional career, he played for nine minor-league clubs in six different leagues: Binghamton, Macon, Topeka, Des Moines, Kansas City, Buffalo again (by now a minor-league club), Wilkes-Barre, Scranton, and Flandeau, South Dakota. His final professional baseball appearance was with the Flandeau Indians in the Iowa-South Dakota League in 1902. During his professional career he had played every position on the diamond, including pitcher and catcher, and had even managed the Buffalo Bisons in 1892.

It has been written that Stearns was one of the first Jews to play major-league baseball. Although this assertion is almost certainly inaccurate, it gained some credence through a quotation included in Peter Levine’s book about sport and the American Jewish experience. Levine quoted approvingly a newspaper item stating, “Dan Stearns of the Kansas City team is said to be a Hebrew. He is the only one of the Chosen People engaged in professional ballplaying.”3

Dan’s mother, Ellen Murphy, was born in Ireland. She could have been a real-life Abie’s Irish Rose, but that is highly unlikely. Dan Stearns was not regarded by most baseball researchers as Jewish. Baseball Almanac has published a list of 163 Jewish major leaguers, including those with only one Jewish parent and those who converted to Judaism.4 Stearns is not listed. The most definitive work on Jewish ballplayers is the Boxermans’ two-volume set Jews and Baseball. They state that prior to 1900 only six Jews had made it to the majors.5 Dan Stearns is not among them. A clue to his religion is found in his final resting place. Stearns is buried in a Catholic cemetery.

In 1884 Dan Stearns married his wife Julia. They had one child – a daughter, Helen, born in 1886. After retiring from baseball, Stearns worked in Buffalo for more than 20 years. In the 1900 census he was recorded as a city policeman. In 1905 he was a clerk at the U. S. courthouse in Buffalo. In 1920 he was reported to be a court officer, and his daughter Helen was a bookkeeper at the same courthouse. Sometime in the 1920s Dan and Julia moved to Glendale, California.

Daniel Eckford Stearns died in Glendale, California, on June 28, 1944, at the age of 82. He was buried in the Calvary Cemetery in Los Angeles. Julia died slightly more than three months later, on October 7, 1944.

Stearns was never a great star, but he went as far as his limited talents would take him. He spent more than two decades in professional baseball. He worked his way up from a clerk to an officer of the court in the United States Courthouse in Buffalo. He was married to his Julia for sixty years. He must have done some things right.

Sources

ancestry.com

baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 The Baseball Encyclopedia, 9th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1993, 74-75.

2 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds, New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948, 26..

3 Peter Levine, Ellis Island to Ebbets Field, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992, 203.

4 Baseball-Almanac.com

5 Burton A. Boxerman and Benita W. Boxerman, Jews and Baseball, vol. 1, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007, 8.

Full Name

Daniel Eckford Stearns

Born

October 17, 1861 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

Died

June 28, 1944 at Glendale, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.