Dick Armstrong

When considering the life of Dick Armstrong, most contemporaries think only of his ample accomplishments in the theological world. This is for good reason. Armstrong spent six decades of his life as a noted Presbyterian minister, pastor, educator, author, and humanitarian. Yet he had more than one career, and there is so much more, from a baseball perspective, about his life to tell.

When considering the life of Dick Armstrong, most contemporaries think only of his ample accomplishments in the theological world. This is for good reason. Armstrong spent six decades of his life as a noted Presbyterian minister, pastor, educator, author, and humanitarian. Yet he had more than one career, and there is so much more, from a baseball perspective, about his life to tell.

Before his call to the ministry in 1955, Armstrong was a rising star in professional baseball administration. After a brief minor-league career as a pitcher/infielder (1947), he became business manager of the Portsmouth (Ohio) A’s of the Ohio-Indiana League in 1948. He then became the first public relations director for the Philadelphia Athletics, working for and with the legendary Connie Mack from the end of 1949 through the end of the 1952 major-league season.

After taking a year to work for an advertising agency, Armstrong answered the call of his hometown Baltimore Orioles, new to the American League in 1954, by becoming their first public relations director. Besides helping establish major-league baseball in the Baltimore market, Armstrong displayed vision with many of the innovations he introduced at the major-league level. This included the first comprehensive in-stadium fan survey ever done in the major leagues, the results of which gained national attention and had lasting influence in the way major-league clubs viewed their fan bases.

By 1955, Armstrong’s growing reputation among major-league executives indicated a long, successful baseball front-office career ahead. However, the time with the Orioles would not be the last calling that he would fulfill.

Even though this biography focuses on Armstrong’s baseball career, the entirety of his life story cannot be ignored. He started a song ad service for the W.W. Orr Advertising Agency, adding to their already unique offering to clients. Late in life, he expressed his hope that his voluminous store of unpublished poetry will eventually be made public. Indeed, if his story were to have a title, it could be “The Poet of the Press Box and the Pulpit.”

Richard Stoll “Dick” Armstrong was born in Baltimore, Maryland on March 29, 1924, the son of Herbert Eustace Armstrong and Elsie Davis Stoll Armstrong.1 Calling his childhood “an idyllic life,”2 Dick attended the McDonogh School in Baltimore for 11 years. He credited this private, semi-military academy for the development of his values later in life. Dick’s lifelong passion for sports began at McDonogh under his father Herb, who was head of the math department and athletic department, also serving as head coach of the varsity football, hockey, and basketball teams. A gifted athlete, Herb had been a three-year All-American for the Tufts College baseball team. The shortstop went on to play professionally from 1917 through 1925, rising as high as the International League, while also pursuing a teaching career.3

At McDonogh, Dick excelled in baseball, basketball, and football while winning awards for excellence in studies.4 He led his class 10 out of 11 years, he received the Childs’ Cup for the highest three-year scholarship average in the upper school, he served as secretary of his class, was editor of the yearbook, captain of the baseball team and co-captain of the basketball team as well as the starting left end on McDonogh’s football team. Armstrong’s academic success and prowess on the pitching mound earned him the Maryland Regional Scholarship to Princeton University in 1942.

The United States was already fighting the Axis powers in World War II when Armstrong entered Princeton as a freshman in the spring of 1942. He began as a member of Princeton’s ROTC unit and then decided to enlist in the U.S. Navy on December 20, 1942. He was assigned to the Navy V-12 unit at Princeton, so he was able to continue his studies, now as a Navy plebe, in preparation for Midshipmen Officers’ Candidacy School. He immediately excelled in athletics, spending one season on the varsity basketball team while winning the Underclassman Cup for baseball in 1943.5 He lettered in varsity baseball in 1944.

From the outset of the war, colleges and universities in America experienced a decline in enrollment. Men were either being drafted into the military or enlisting voluntarily. The U.S. Navy also had a critical need for commissioned officers. To address both areas, on July 1, 1943, “The Navy V-12 program was created to generate a large number of officers as well as to offset the dropping number of enrollees at colleges.”6 Armstrong qualified for Harvard University’s Midshipmen School, earning a commission as an ensign after four months. He then spent the next eight months in the Naval Supply Corps School at the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration. After completing training at Harvard in the spring of 1945, Armstrong was assigned as the disbursing officer on the U.S.S. Chandeleur (AV 10) in the Pacific theater. He was later promoted to supply officer and remained on sea duty until his honorable discharge on August 31, 1946.7

Armstrong noted fondly that he pitched for Princeton both before and after the war. He returned to college determined to spend his senior year “as a regular student.”8 Besides earning his undergraduate degree in economics, he was a starting outfielder and pitcher on the varsity baseball team during the 1947 season. In 1990, Armstrong was awarded the Robert L. Peters. Jr. ’42 Award, by the Friends of Princeton Baseball, honoring “an alumnus…for significant contributions to the athletic community and later-life accomplishments.”9

As he contemplated graduation, Armstrong wanted to play professional baseball. A fellow Baltimorean, Arthur Ehlers, was farm director of the Philadelphia A’s. Traveling to Shibe Park in Philadelphia after graduating, Armstrong introduced himself to Ehlers. An astute executive with an eye for talent, Ehlers became one of the most important acquaintances in Armstrong’s baseball life. Beyond Armstrong’s on-field talent, Ehlers spotted a business sense and leadership qualities in the young man. He offered Armstrong a job with the A’s, first as a pitcher and utility infielder in their minor-league system in 1947.

After a short stay at Martinsville (Virginia) in the Carolina League, Armstrong was sent to the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Red Roses of the Interstate League. As an infielder, Dick found himself backing up future Hall of Famer Nellie Fox. “I didn’t get to play much,” Armstrong told the Germantown Courier in April 1962.10 Late in the season, he was given a start on the mound against Wilmington. He was relieved after six innings with the score tied at 3 to 3. He was also scheduled to pitch the final home game of the season, but it was rained out. Armstrong recalled what happened next. “The A’s were just starting a farm system, and at the end of my first season he (Ehlers) called me into his office and said, ‘Look, you’re getting married soon, and you’ll have a family to support. How long do you want to bang around in the minor leagues wondering if you’ll make it to the majors?’ He suggested that I should consider the front office, which I thought was the best news I’d ever heard. I was thrilled!”11 Ehlers then offered Armstrong a position in the A’s minor-league business operation, and he jumped at the chance.

In autumn 1947, Ehlers sent his young protégé to a business manager’s conference in Columbus, Ohio. He then named Armstrong as the first business manager of the Class-D Portsmouth A’s. Armstrong had to build the new club’s operations from scratch on a low budget. According to J.G. Taylor Spink, “Armstrong had to do everything except sell peanuts. He put in lights, erected a new scoreboard, dressed up the park, made contacts here and there, built a new diamond.”12 Spink also referenced special events created by Armstrong.

As business manager, Armstrong was responsible for 29 different financial accounts. Figuring that total attendance of 75,000 was needed to break even, he developed a detailed marketing and promotional strategy, which included printed pocket schedules, newspaper ads, media relations, signage, and community goodwill. His plan, in a harbinger of things to come, also included a detailed, 37-question survey that shed light on the wants and needs of the Portsmouth fan base. Armstrong reached out to numerous community groups, including youth, business, and fraternal organizations. He organized special nightly promotions. One such promotion was a “Sweetheart of the A’s” contest that the local newspaper quickly dubbed as the “Pretty Girls in Bathing Suits Night.”13 According to Armstrong, the A’s players were commissioned to judge the winning contestants on the field. However, they came to him the morning of the event with other plans. They intended to award the “sweetheart” prize to Mrs. Margie Armstrong, a favorite of theirs. “You can’t do that!” Dick told them, and the players reverted to the original plans.14 Armstrong and Margaret Frances Childs of Princeton met while Dick attended the Harvard Business School during the war and Margie attended nearby Wellesley. They married in January 1948, and she assisted Dick very ably as a goodwill ambassador in Portsmouth during those early days.

Total paid attendance for the 1948 Portsmouth A’s was 73,533, which led the Ohio-Indiana League. Armstrong described his business manager duties as “entertainment, exhibition and sport all at once.” His stated objective of “reviving interest in professional baseball and getting people in the habit of coming out to the park” worked thanks to his vision and goodwill. Portsmouth’s Central Labor Council, in The Labor Review, said, “He came here as a total stranger. Because of his fine personality, his recent adherence to his duties, his fine cooperation with the fans and genuineness and straight forwardness, he won the respect of all.”15

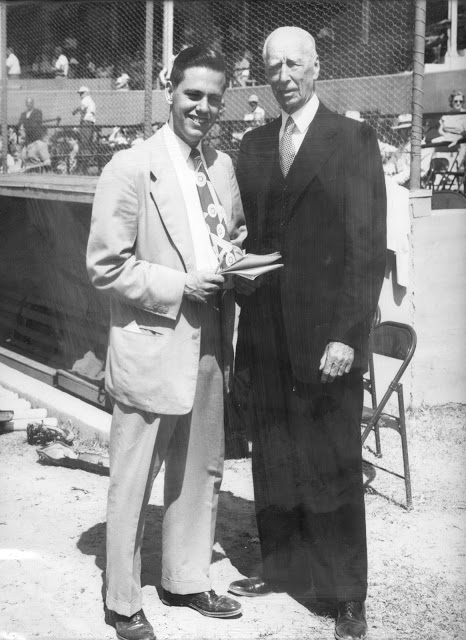

Armstrong returned to Portsmouth in 1949 and organized a “Connie Mack Day” in July, giving residents a chance to glimpse of the “Grand Old Man of Baseball” who brought the game back to Portsmouth. The event drew a sellout crowd to the ballpark that evening. Despite a serious bus accident that injured 11 players, the 1949 A’s won the Ohio-Indiana League championship and were a success both on the field and at the box office.16 Art Ehlers sensed he had a rising front-office star on his hands.

The major leagues evolved into a big business after the down years of the Great Depression and World War II. By the late 1940s, public relations became increasingly important — clubs realized that it took more than a good team on the field to put people in the seats. They formed agreements with outside advertising and PR firms to assist in their promotional efforts. Mack’s A’s were at the end of a two-year contract with the Adelphia Associates and sought proposals for a new contract for the 1950 season and beyond.17 Industry heavyweights like Robert G. Wilder and Co., the John LaCerda Agency, Gray and Rodgers Advertising, and W. Wallace Orr, Inc. all bid for the A’s business. Ehlers, thinking that the 25-year old Armstrong was more than up to the task of running publicity for the A’s, suggested that Dick submit a proposal of his own. In October 1949, Armstrong submitted his “Suggested Public Relations and Publicity Program for the American Baseball Club of Philadelphia,” focusing on an elaborate, year-long celebration of Connie Mack’s 50th anniversary as manager of the A’s. He also submitted a separate “Source of Attendance” study.18 His was the only proposal that focused on Mack’s Golden Jubilee; only one other bidder even mentioned it.19

Liking what they saw and seeing an opportunity to move the function in-house at a fraction of the cost, Connie Mack and his sons Roy and Earle brought Armstrong into the A’s front office to run public relations, with the part-time assistance of Eddie Hogan, who worked publicity for the Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League.

Liking what they saw and seeing an opportunity to move the function in-house at a fraction of the cost, Connie Mack and his sons Roy and Earle brought Armstrong into the A’s front office to run public relations, with the part-time assistance of Eddie Hogan, who worked publicity for the Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League.

Armstrong wasted no time in getting right to work before the beginning of the 1950 season. Calling Dick “a young man with ideas,” J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News took notice of what Armstrong was doing and described it thus:

“He set out to discover what the public and the press thought about the Athletics. He toured the city for three months without disclosing his identity, asking questions of taxi drivers, salesmen, bankers, businessmen…inviting complaints, accepting the good points. He jotted down his findings and explorations in a 30-page report for future reference. Hoping that the A’s would have a good club in 1950, he went to work and his anniversary campaign for Mr. Mack’s fiftieth year…was tremendously well-handled.20

The plans for Mack included the establishment of the Golden Jubilee Committee of Philadelphia, consisting of prominent business and community leaders as well as luminaries from throughout the major leagues. Many radio and television appearances for Mack, national magazine and newspaper publicity, and celebrations at all American League stadiums were scheduled, as well as a gala dinner in Philadelphia in April 1950. Armstrong collaborated with Ed Hogan and local Philadelphia newspapermen in publishing the “50th Anniversary Golden Jubilee” Philadelphia A’s yearbook. For the jubilee, Armstrong composed “The Connie Mack Swing,” a musical score featured in the yearbook and performed by the Philadelphia Police and Fireman’s Band at Mack’s Shibe Park celebration in 1950.21 Armstrong also wrote “The A’s Song,” the score of which appeared in the 1951 team yearbook.

Besides his musical compositions, Armstrong also worked his passion for poetry into his public relations toolkit. In 1949, the A’s set a still-standing major-league record by turning 217 double plays. They went on to accumulate a three-year total of 629 DPs, a record that stands even today with the longer playing seasons. Most of these involved their keystone combination of shortstop Eddie Joost and second baseman Pete Suder, along with first baseman Ferris Fain. Armstrong quickly took notice. Using the meter of Franklin Pierce Adams’ famous “Tinker to Evers to Chance,” he composed a tribute to the A’s record-setters, which was published as a press release after the 1951 season. Armstrong also posted “Joost to Suder to Fain” on his blog in 2012.

If only the 1950 A’s could have cooperated on the field. Instead, the club finished last at 52-102, six games behind the seventh-place St. Louis Browns and a full 46 games behind the pennant-winning New York Yankees. To rub salt in the wound, the Philadelphia Phillies “Whiz Kids,” who shared Shibe Park with the A’s, made an unexpected run to the NL pennant, further diverting attention from the A’s. Attendance fell and Connie Mack’s health began to fail, causing him to miss some late-season games. He retired as manager at the end of that season.

Despite the disappointment from Mack’s decline and the team’s performance, Armstrong had already taken steps to modernize the fan experience both in and outside of Shibe Park. His energetic plan caught the attention of veteran observers. Calling Armstrong “a young man with ideas,” J.G. Taylor Spink summarized the innovations that October:

“The results of his suggestions, energy and experience are already evident in: 1) The establishment of a Connie Mack Shrine at Shibe Park, a room which will house all the trophies, souvenirs and mementos presented to Mr. Mack — starting from the original glove used by the famed manager, 2) The formation of an Athletic Club patterned after Larry MacPhail’s Stadium Club at the Yankee Stadium and limited to holders of season ticket plans — with space for refreshments and meals, 3) The setting up of a bureau of information which will work hand-in-hand with the manager and general manager so that news is given out according to plan, 4) The organization of a department which will plan added entertainment to games, 5) The formation of a policy of courtesy education for all club employees in their dealing with the public, and 6) The establishment of a sound ticket sale plan.”22

Fan publications became a staple of Armstrong’s publicity efforts. He and Eddie Hogan had early on established The Elephant Trail, a monthly newsletter highlighting player profiles as well as current and future events. In 1951, Armstrong established a relationship with Jay Jackson, producing an A’s yearbook that served as a model for all major-league clubs. Jackson’s firm, Jay Publishing Company, through its subsidiary Big League Books, quickly received the contract to produce all major league yearbooks. It did so, along with photo packs and other publications, through the mid-1960s.23

By 1952, the Mack family was engaged in an internal fight for ownership of the club as it struggled to stay solvent. Rent collected from the Eagles and the Phillies, who shared Shibe Park, kept the club afloat.24 Undeterred, Armstrong continued his quest to bring fans to the ballpark by holding creative promotions and unusual events. One involved pitcher Bobby Shantz, the little lefthander whose 24-7 record for the A’s earned him the American League MVP award in 1952. Shantz always was the subject of good-natured controversy about his slight stature and weight, with many trying to guess just how much below 5 feet 10 inches he stood. Armstrong saw an opportunity to end the debate, and with Shantz’s cooperation, staged a ballyhooed “weigh-in” at Shibe Park. On July 18, 1952, representatives from the Philadelphia Bureau of Weights and Measures, Shantz, and A’s manager Jimmy Dykes gathered at home plate. Shantz stepped up to the scale, and his “tale of the tape” officially came in at 5 feet 6 ¼ inches tall with a weight of 139 ¾ pounds. Shantz’s size obviously had no effect on his pitching, but the coverage of the event in the Philadelphia Inquirer was a publicity coup for Armstrong and the club.25

Powered by the stellar pitching of Shantz and the offense of Ferris Fain, the A’s rebounded to fourth place in 1952, finishing 79-75. Attendance rose to 627,100. It was the last time A’s attendance in Philadelphia broke 600,000, and after dismal 1953 and 1954 seasons, the club was sold and moved to Kansas City in 1955.

By 1952, Dick and Margie had two small children. Being a baseball executive was a grueling job requiring long hours away from home. Armstrong was unsure if he wanted to spend the coming years away from his family for those many hours while the kids were growing up. He also felt that he would enjoy the creative challenges of branching out into the advertising field. At the end of the 1952 season, the W. Wallace Orr Agency offered Armstrong an irrefusable opportunity to become their copy and plans director. Eager to explore new opportunities and to settle down to more regular hours, he left the A’s. Upon the announcement of his departure, a writer from the Baltimore Sun stated, “The rise of young Dick Armstrong…in the public relations forces of the Philadelphia Athletics, was as rapid as his tenure was short…(he) gives off evidence of being headed into quite a career. He even made the A’s sound really good”26

Even though Armstrong technically left the game, he never strayed far from it or the sports world. The Orr Agency entered into an agreement with the A’s to provide designs for promotional and advertising materials, with Armstrong as the account executive. Also, the Milwaukee Braves, freshly moved from Boston during spring training in 1953, urgently needed marketing materials and turned to the Orr Agency for help. Edward D. Barker, Orr’s Vice-President, described Armstrong’s contribution to the project. “(Teaming with Art Director, Dick Andrews) a major project for the Andrews-Armstrong team was the preparation of a two-color ticket brochure, which was designed, written, proofed, printed, and en route to Milwaukee in a span of five days…Considering the immense amount of creative material that had to be turned out…this was indeed a remarkable promotional job…it was a little short of amazing.”27

Dedicated sports telecasting was in its infancy in 1953, and Wallace Orr was at the forefront with its subsidiary Tel Ra Productions, which produced unique and original sports magazine-type programming and possessed one of the largest collections of sports filmography in the world.28 Tel Ra’s “TeleSports Digest,” a weekly show, was an original forerunner of ESPN’s “SportsCenter” format. Armstrong settled in to the TV end, producing plans and proposals for sports programming for Tel Ra’s “A Salute to Baseball” and “Major League Preview” as well as the first “Eagles’ Nest” television program for the Philadelphia Eagles.29 Once again, Armstrong easily acclimated to the business end of the new sports broadcasting production field. Thus, a long career beckoned, especially as an industry pioneer.

Then came the announcements from St. Louis and Baltimore of the second major-league franchise shift in as many years.

The Browns had long played “second fiddle” to the Cardinals in the Gateway City, struggling both on the field and financially. After the Anheuser-Busch brewing company purchased the Cardinals, their hold on the city was solidified, making the Browns expendable. In 1953, Browns owner Bill Veeck reached an agreement with a Maryland group led by attorney Clarence W. Miles to sell the franchise. Miles then purchased the Baltimore Orioles of the International League from Jack Dunn III. Under Dunn and business manager Herb Armstrong — Dick’s father — the O’s were one of the most successful minor-league operations. Strong attendance in Baltimore caught the attention of the major leagues. Baltimore was awarded a franchise in the American League and Richmond, Virginia, won an IL franchise. With Dunn III and Herb Armstrong each assuming roles in Miles’ new front office, the club continued its tradition. It kept the Baltimore Orioles name and began play in 1954. The O’s brought in Jimmy Dykes and Art Ehlers from the Philadelphia A’s as manager and general manager respectively. In a forerunner of the expansion era, it fell to Dykes and Ehlers to take the patchwork roster and make it major league in all respects, which included selling it to the Baltimore community. Ehlers immediately knew who he wanted to lead the public relations effort.

Upon reading the announcements out of Baltimore, Armstrong immediately sensed what would happen next. Before ever receiving a call from Ehlers, he and Margie discussed the possibility of joining the Orioles’ front office. They were torn because the Orr Agency was providing exciting work with a more relaxed schedule. They decided to keep an open mind, since an opportunity to be on the ground floor of building major-league baseball in Armstrong’s hometown was certainly appealing. Ehlers called the very next day, informing Armstrong that he had already recommending him to the owners as the Orioles’ first PR director. Armstrong said he was interested, as long as the salary met his and Margie’s expectations.30 He had one other reservation about the job, a personal one. He was concerned that some would perceive nepotism because his father was in the front office, even though it was Ehlers’ idea. After talking it over with his dad, they both agreed that it would become common knowledge that the two Armstrong men came to the Orioles under separate circumstances.31 Clarence Miles agreed to Dick’s salary request, paving the way for his return to the majors.

There was much work to be done in very little time. Promotional materials, advertising strategies, and ticket plans had to be created. Media outlets had to be prepared to carry the new club’s message to the region’s residents. Excitement gripped Baltimore, and on April 15, 1954, led by Vice President Richard Nixon, hundreds of thousands lined the city’s streets in a mammoth welcoming parade. Lavish floats and marching bands were joined by baseball dignitaries and Orioles players in what was described as the largest parade in Baltimore’s history.32 Later that afternoon, more than 46,000 fans jammed the still unfinished Memorial Stadium to see the O’s defeat the Chicago White Sox, 3 to 1. Even with this auspicious start, Armstrong knew that he had to understand the pulse of the Baltimore fan base to assure long-term success at the box office. He set out to conduct the largest comprehensive, in-stadium fan survey ever attempted by a major-league baseball team.

Armstrong was no stranger to public opinion polling and survey methods. He’d worked for the Gallup organization during the 1948 presidential election campaign.33 He’d also taken smaller fan samplings during his time with both Portsmouth and Philadelphia. Armstrong sought to gather useful information with “a cross-section of opinion about various phases of (the club’s) operation…(and) hoped to obtain some vital information about the people who attend games.”34

The survey was taken inside Memorial Stadium during 20 games in July and August 1954. Approximately 100 to 150 questionnaires were handed out at the beginning of each game, and all were collected by the end of the third inning so that the game score wouldn’t influence responses. Fans participated eagerly, with 97% of the surveys completed and returned. Information was sought on seat pricing and ticket sales as well as game starting times. Fan experience, the average cost of attending a game, stadium appearance, and between-inning music tastes were queried. Opinions on transportation, parking, and radio and television coverage were also sought. In all, the fan survey was designed to draw conclusions about the “average Baltimore fan” of 1954.35

After Armstrong and his staff meticulously tabulated the results during the off-season, a comprehensive report was submitted to the club ownership and the press. The concept of a baseball club polling the needs and wants of its fan base drew national attention. Baseball press and management, from the commissioner on down, took notice. The Sporting News, in its January 19, 1955 editorial, opined as follows:

“Baltimore is a relative newcomer to modern major league baseball, but the Orioles front office has already made a lasting impression on the men who run the game…Latest evidence of the Orioles’ wide-awake approach is the poll conducted by publicist Dick Armstrong and printed in these pages last week. The young tom-tom beater is by no means the first to sample fan opinion, but the comprehensive nature of his questionnaire and the useful information produced by it seldom have been matched by similar endeavors…Both majors and minors profitably can emulate the Baltimore survey…There is no sounder way to good public relations, no surer method of attracting more fans to the ticket windows.”36

A United Press article from May 17, 1955 stated, “Commissioner Ford Frick announced today his office has employed Steven Fitzgerald and Co. of New York, an independent research organization, to make a study of all the problems facing baseball.” Bernie Lit, in his “Baltimore Nite-Life” column, wrote to his readers, “Dick Armstrong, the fabulous pubbie great for our beloved Baltimore Orioles, rated a mention in most of the dailies around the country on how Baltimore fans are so sports-minded. And just like the fans and our Birds, Dick Armstrong, YOU, too, are Big League.”37

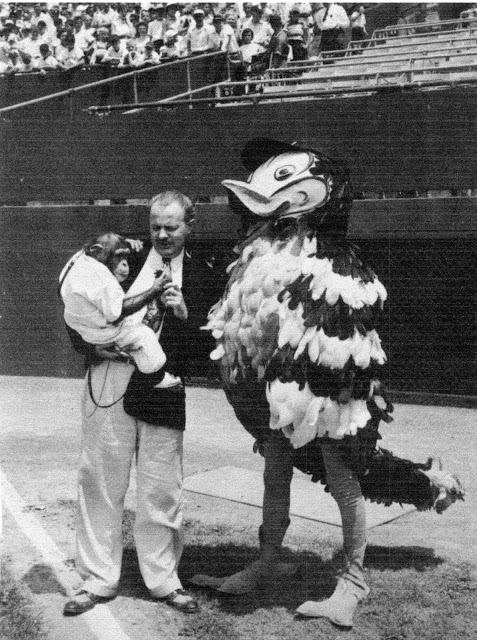

Armstrong further demonstrated his creativity by introducing “Mr. Oriole,” the first on-field, in-costume mascot in the major leagues. Early in 1954, he ran a contest for local artists to submit Oriole caricatures as a logo and symbol of the team. Armstrong remembered, “I was looking for a jaunty but likeable bird, one with plenty of personality…one stood out above all the rest…submitted by Jim Hartzell, a cartoonist for the Baltimore Sun. We named our new mascot ‘Mr. Oriole’ and his perky bird face was quickly popularized.”38

Armstrong further demonstrated his creativity by introducing “Mr. Oriole,” the first on-field, in-costume mascot in the major leagues. Early in 1954, he ran a contest for local artists to submit Oriole caricatures as a logo and symbol of the team. Armstrong remembered, “I was looking for a jaunty but likeable bird, one with plenty of personality…one stood out above all the rest…submitted by Jim Hartzell, a cartoonist for the Baltimore Sun. We named our new mascot ‘Mr. Oriole’ and his perky bird face was quickly popularized.”38

Armstrong had an additional idea for Mr. Oriole that ultimately led to the prevalence of future mascots. He wondered “if it would be possible to create a costume that would replicate the expression and appearance of Mr. Oriole so that a three-dimensional version of the bird could cavort on the field and in the stands during the games.”39 Armstrong’s long-time friend and high school teammate, Johnny Myers, knew a costume designer who happened to be related to Hall of Famer Joe Tinker. Using the cartoon Mr. Oriole as a model, (the designer) Tinker produced an excellent costume likeness of the bird. Myers was an accomplished trumpeter and a natural performer. Armstrong convinced him to dress in the suit and take his act to the ballpark. “When the strikingly colorful bird made his first public appearance at Memorial Stadium following a proper introduction over the public address system, the fans went wild,” explained Armstrong, “but the pièce de resistance was when he whipped out from beneath one of his feathered wings a trumpet, which he could play through his beak…the effect was sensational! We had the only trumpet-playing bird in captivity!”40

Although the 1954 Orioles finished seventh at 54-100 record, the team drew more than 1 million fans, a testament to the awareness created by Armstrong’s PR office, as well as baseball’s appeal to the people of Baltimore. Paul Richards was brought in as both manager and general manager, ushering in an era of player development that would lead to a strong contender by 1960.

Meanwhile, the Armstrong family had received a stunning blow in the late spring of 1954. Their three-year-old son Ricky was diagnosed with leukemia, which then had no known cure. Dick and Margie dedicated themselves to fighting Ricky’s disease with all available treatments. When Armstrong originally took the Orioles job, he agreed to a two-year contract because he was still unsure whether he wanted baseball to be his life’s work. This changed after long conversations with Margie and with friends and co-workers Jack Dunn III and Orioles broadcaster Ernie Harwell. Armstrong decided that his best future path was in baseball, including the goal of eventually becoming a general manager.41 He approached the 1955 season with increased resolve and purpose. As he and his family arrived in Daytona Beach, Florida for spring training, their baseball future appeared to be well defined.

Non-baseball people have the romantic notion of spring training as being a relaxing time spent in the sun and away from the cold winters up north. For baseball front office personnel and the press, the exact opposite is true. For Dick Armstrong, spring training in 1955 presented some challenges. The first was adjusting to the working style of Paul Richards to assure that the official press announcements from Armstrong’s office mirrored what Richards was informally conveying to the writers. Second, Richards had already reshaped the Orioles roster in the off-season, which included a record 17-player trade with the New York Yankees in November 1954. Biographical information of all the new players had to be written and, most importantly, publicized to the fan base through the baseball writers.

Armstrong’s days started early and ran late. He could spend time with his two older children, Ellen and Ricky, only in the early mornings (the famiily also included a small boy named Andy by then). Dinner with Margie was normally accompanied by associates of the club or members of the press. Private moments were few and far between, but Armstrong enjoyed the pace and the challenges of the job.

One evening, he and Margie decided to dine by themselves to catch up on family chatter. They were driving back from the restaurant after an enjoyable evening when an event occurred that altered their lives forever. Armstrong explained it this way:

“Margie and I were calmly chatting, when — without warning — something strange and wonderful happened. I was suddenly seized by an overpowering feeling that God was speaking to me! So irresistible was the sensation that I immediately pulled over on the wide shoulder of the road and stopped the car. I sat there tensely gripping the wheel, with what must have been a stunned expression on my face, staring at nothing. Margie was startled. She was afraid I was having a heart attack. ‘Are you all right?’ she asked, worriedly…I turned toward her and said in a tone that reflected my bewilderment, ‘I have the strangest feeling that God is telling me that I must become a minister!’”42

Armstrong was a self-professed “biblically illiterate Episcopalian.”43 Though he believed in God, he did not read the Bible, never went to Sunday School, and attended church only once in a while. Yet, convinced that what he felt in the car was genuine, he spent the night discussing it with Margie. They both agreed that he had to pursue this calling.

Armstrong later came to call this moment his “Damascus Road” experience, drawing from the Book of Acts (Chapter 22, verses 10-11 in the Revised Standard Version). “And I said, ‘What shall I do, Lord?’ And the Lord said to me, ‘Rise, and go into Damascus, and there you will be told all that is appointed for you to do.’ And when I could not see because of the brightness of that light, I was led by the hand by those who were with me, and came into Damascus.”

He decided not to share it with the Orioles front office right away. He first consulted with a local church pastor in Daytona Beach, who assured him that what he felt was indeed possible and a work of God.

Armstrong did not know how to pursue being a minister, and he could not disrupt his duties with the Orioles until he better understood the plan he needed to put in place. He had a lot of work to do, both in the press box and on the road to the pulpit. At times he questioned what happened to him that evening in Daytona Beach, because it was such a radical departure. “Throughout my years in baseball and advertising I had toyed with many interesting ideas, but never had I had the slightest inkling about being a minister, nor had anyone ever suggested the ministry to me. It was not a matter of ruling out the possibility; the thought had never occurred to me,” he recalled years later.44

After spring training, Armstrong shuttled between his front office duties and various appointments with family to discuss what his next moves would be. He received strong guidance from his cousin Maurice Armstrong, a Presbyterian minister in Philadelphia. Maurice suggested meeting with Dr. John Mackay, president of Princeton Theological Seminary and a noted Presbyterian. When Dick later mentioned this to Margie, she excitedly reported attending high school in Princeton with the Mackay children and that her parents had developed a deep friendship with the Mackays during those years. Margie’s parents supported their plans and made the call, setting up an appointment for Dick to visit with Dr. Mackay.

After spring training, Armstrong shuttled between his front office duties and various appointments with family to discuss what his next moves would be. He received strong guidance from his cousin Maurice Armstrong, a Presbyterian minister in Philadelphia. Maurice suggested meeting with Dr. John Mackay, president of Princeton Theological Seminary and a noted Presbyterian. When Dick later mentioned this to Margie, she excitedly reported attending high school in Princeton with the Mackay children and that her parents had developed a deep friendship with the Mackays during those years. Margie’s parents supported their plans and made the call, setting up an appointment for Dick to visit with Dr. Mackay.

Not all of the feedback that Armstrong received from family and others was completely supportive and understanding of the abrupt career change that he planned. First, there was the immense responsibility of having the means to support Ricky’s ongoing treatments; a move to seminary would certainly cause financial struggle. The Pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Princeton, Dr. John Bodo, felt that Dick’s calling might be better served in the lay community, given the high visibility of his position in baseball. Inevitably, there was also a suggestion that perhaps Armstrong’s decision was solely a reaction to Ricky’s illness. He strongly denied that, recalling, “Had I for one moment suspected that my desire to become a minister was the result of Ricky’s illness, either as an attempt to bargain with God for Ricky’s life or to atone for whatever I may have done to cause God’s disfavor, I would still be in baseball, because I would have suspected my motives.”45 In his heart, Armstrong believed that God wanted him to become a minister. The road then became more defined.

At his meeting with Dr. Mackay, Armstrong related his Damascus Road experience and his belief that God wanted him to serve a congregation, hence his desire to enter seminary. He also told Dr. Mackay that he “knew very little about these things” because he was, after all, “a public relations man, not a theologian.”46 What might have been a throw-away line turned into one of the most important things that Dick could have said to Mackay. “Oh Boys! Oh Boys! This is providential!” he (Mackay) exclaimed with great enthusiasm. “The trustees have just authorized me to hire a public relations person for the seminary and now God has sent one into my office! If you would be interested in working for us part-time while going to seminary, I think we could work something out.”47 Providential indeed — Armstrong got not only a boost for his seminary application but also an opportunity to earn income while studying. His acceptance letter arrived shortly thereafter.

In the summer of 1955, Armstrong redoubled his work for the Orioles, wanting to leave the public relations office in good shape for his successor. After notifying the Orioles in May of his decision to leave at the end of the season, he immediately set out to compile and write a comprehensive report, entitled “Public Relations Report for the Baltimore Baseball Club, Inc.” It was a “how to” manual for any public relations department and director as well as a program specific to the Orioles’ unique operation.48 It was a hectic summer because he and Margie not only handled work with the Orioles but also relocated the family to Princeton while dealing with Ricky’s illness. Ricky’s periods of remission were becoming shorter, and Armstrong recalled, “In between his temporary recovery would be days of terrible suffering, usually involving hospitalization, blood transfusions and painful treatments.”49

The baseball season was winding down, and the new seminary semester was approaching. Armstrong was traveling frequently between Baltimore and Princeton. September 16 was “Firemen’s Oriole Appreciation Night” between games of a doubleheader with the Washington Senators. The event was sponsored by the firefighters of metropolitan Baltimore. In a tribute, the firemen renamed the night “Dick Armstrong Night,” during which he received gifts and was able to say goodbye to the fans at Memorial Stadium.50 On September 26, Clarence Miles hosted a dinner in Baltimore for the club owners, key fans, the press, and other dignitaries. He asked Dick and Margie to attend as guests of honor in one last tribute. Ricky had taken a turn for the worse, so Margie decided to stay behind. As Armstrong set out for the train to Baltimore, God once again signaled, telling him to return home because he was needed there for Margie and Ricky. Ricky died in Dick’s arms at 4 o’clock the next morning.51

Armstrong spent the next three years as a Masters of Divinity student at Princeton Seminary. He brought the same zeal to his studies for the ministry as he did to his baseball front office duties, winning the Grier Prize for Speech and Homiletics, serving as an assistant to the vice president for public relations, and becoming seminary student body president.52 Another son, William (“Woody”) was born in 1956. Upon Armstrong’s graduation in 1958, he, Margie, Ellen, and sons Andy (then five) and Woody (two) awaited the next stop in their journey.

Leaving baseball did create a particular void for Armstrong. “Whatever sadness I felt about leaving baseball had to do not with its material benefits but with the severing of ties with the game I had loved all my life and the friends I had made along the way,” he remembered. “Anyone who loves sports can understand that feeling.”53 However, he still remained connected to the sports community. In May 1955, he had received an unexpected phone call from Don McClanen, former basketball coach at Eastern Oklahoma A&M. McClanen was starting an organization called the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. As Armstrong recalled, “Along came something relating sports to Christ.”54 The FCA, which involves athletes young and old, of all races and Christian denominations, both men and women, became a big part of his life.

Armstrong joined a group of sports luminaries in the original organization of the FCA. They included baseball executive Branch Rickey, former member of the Phillies “Whiz Kids” and future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, Cleveland Browns quarterback Otto Graham, Cleveland Indians Hall of Famer Bob Feller, and Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine, among many others. Don McClanen recalled, “He (Armstrong) became a vital partner and indispensable colleague in shaping and enabling the mission of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. In the early days…he served as a most needed interpreter of the unfolding vital relationship being forged between religion and sports.”55 Besides founding local FCA chapters in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Princeton among other cities, Armstrong served for many years on the Fellowship’s National Board of Trustees. He was the first recipient of the FCA’s Distinguished Service Award in 1965, received the Branch Rickey Memorial Award in 1974 and was elected Life Trustee in 1979.

The accomplishments of Dick Armstrong’s ministerial career are almost too numerous to list. After ordination to the Presbyterian ministry in 1958, he served for ten years as Pastor of the Oak Lane Presbyterian Church, an urban church in Philadelphia. His highly successful program, “Operation Black and White,” which focused on evangelism in the neighborhood, revitalized a parish whose membership was in decline.56

After Oak Lane, Armstrong returned to Princeton Seminary, becoming director and then vice president of development from 1968 to 1974. He then accepted the call as Pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis, Indiana. He served there from 1974 to 1980, establishing a “Church in Community” ministry, stressing leadership and volunteerism in the larger community. Armstrong became a vital presence in Indianapolis, which included being chosen as a voting board member of the Indianapolis Indians Triple-A baseball club. He also received, among many other recognitions, the Distinguished Service Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (Indiana Region).

In 1979, Armstrong was elected as an Alumni Trustee at Princeton Seminary. In 1980, he returned to the seminary as the first Ashenfelter Professor of Ministry and Evangelism. He retired with Professor Emeritus status in 1990, but continued his activity in various ministries throughout the world. He served in South Africa as a member of the advisory committee for the Centre for Contextual Ministry, University of Pretoria. There he was deeply involved in a program providing educational opportunities at various levels, primarily for black ministers whose education had been stunted by the apartheid system57

Armstrong also served as vice president and then president of the Academy for Evangelism and Theological Education (1987-1991), as well as editor of the academy’s journal (1991-1997). He was the first recipient of the Charles Grandison Finney Award for Excellence in the Teaching of Evangelism.

Love of writing, music, poetry and humor was an ongoing theme in Armstrong’s life, and he was prolific in each area. His many book credits include The Oak Lane Story (1971), Service Evangelism (1979), The Pastor as Evangelist (1984), The Pastor-Evangelist in Worship (1986), The Pastor Evangelist in the Parish (1990), Are You Really Free? Reflections on Christian Freedom (2002), Help! I’m a Pastor (2005), and A Sense of Being Called (2011).

In 1946, while a performing member of the Princeton (University) Nassoons, Armstrong wrote the music, words and arrangement for “The Tigertown Blues,” a song whose tradition continues to this day. The original arrangement appeared in the University’s centennial songbook, Carmina Princetonia, in 1986. A portion of it can be heard being performed by the Nassoons in the 2013 movie Admission.58 Armstrong’s other musical credits, besides the aforementioned “Connie Mack Swing” and “The A’s Song” include “Princeton! Princeton! Princeton!” which he wrote in connection with the University’s 250th anniversary celebration and the 50th reunion of the Class of 1946. The hymn “For Christian Homes, O Lord, We Pray,” to which he contributed verses 1 and 3-5, appears in the Armed Forces Hymnal.

Armstrong authored volumes of both published and unpublished poetry. Humor is often sprinkled into his verse, as evidenced by Enough Already! And Other Church Rhymes (1993). He also wrote two poetic reflections on faith and life: Now That’s a Miracle (1996) and If I Do Say So Myself (1997). Awaiting publication are approximately 3,000 pages of his poetic reflections on books of the Bible.59

“If you live long enough, you soon become the last person to talk about it.”60 That is, nearing the end of his 95th year, Armstrong fondly noted that his longevity made him a surviving witness to particular moments in baseball history. He was, indeed, the last living person from both the front offices of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s as well as the 1954 Baltimore Orioles, and he enjoys circling back to his baseball years by attending events that commemorate this era.

On September 14-15, 2012, the town of East Brookfield, Massachusetts held a 150th birthday celebration of its most famous native son, Connie Mack. It was attended by Mack biographer Norman Macht and Dick Rosen, chair of the Philadelphia A’s Historical Society (both SABR members). Dick Armstrong shared his many memories of Connie Mack, recited “Joost to Suder to Fain,” and played “The Connie Mack Swing” on piano. (A video of this event is available on YouTube.)61

Armstrong’s beloved Orioles commemorated their 60th anniversary with a gala ceremony at Camden Yards on August 8, 2014. As the last survivor of the 1954 club’s front office, he received the distinction of throwing out the first pitch before the game against the St. Louis Cardinals. “After being anxious not to embarrass myself by throwing an errant pitch, I somehow managed to get the ball over the plate,” he recalled.62 He then enjoyed the game with family, friends and ex-Oriole players.

Armstrong continued to live in Princeton. His family included sons Woody and Andy and daughter Elsie, along with seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. His wife Margie died in 2013 and daughter Ellen died on Thanksgiving Day in 2018.

The Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame houses Armstrong’s baseball-related papers, which are available to researchers, historians and writers. Jim Gates, the Head Librarian at the Hall, said of Armstrong, “I had the chance to spend many hours in conversation with Dick and learned so much about baseball from his stories. I think we could have gone on for weeks, as his tales were both educational and entertaining.”63

Quite fittingly, Armstrong’s younger daughter, the Reverend Elsie Armstrong Rhodes, followed her father into the Presbyterian ministry. She became the Pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Cooperstown, within sight of the Baseball Hall of Fame. When asked to sum up her father in a nutshell, the Rev. Rhodes responded this way:

“I can’t think of a person I admire more than my father: for his integrity; his perspicacity and wisdom; for his gifts as a pastor, professor, preacher, prophet, parent — and yes, pitcher, as well; for his creativity, compassion, conscientiousness; and his commitment to social justice and his faithful witness to the ways of Christ.”64

Well said, Pastor Rhodes. No doubt the Poet of the Press Box and the Pulpit is fond of his daughter’s use of alliteration in describing her Dad!

Postscript

Dick Armstrong passed away on March 11, 2019. He would have turned 95 on March 29. Somewhere up above, the Lord’s baseball team now has a PR Director and a chaplain to lead Sunday services.

Last revised: March 13, 2019

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Warren Corbett. Photo credit: CentralJersey.com.

Sources

Armstrong Collection. National Baseball Hall Library, Cooperstown, New York. BA MSS 110.

Armstrong, Richard Stoll. A Sense of Being Called. Eugene. Oregon: Cascade Books, 2011.

Armstrong, Richard Stoll. Minding What Matters (blog). https://rsarm.blogspot.com/p/sports.html.

Baseball Reference.com. “Art Ehlers.” Accessed November 12, 2018. https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/art_ehlers.

Corbett, Warren. “Connie Mack’s Less Than Graceful Exit.” The Hardball Times. Accessed November 27, 2018. https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/connie-macks-less-than-graceful-exit.

Hobart and William Smith College Archives, Geneva, New York. Accessed October 25, 2018. https://hwsarchives.omeka.net/exhibits/show/navy-v-12/wwii-and-the-navy-v-12-program

Princeton University Office of Athletic Communications, press release. “Peters Award Presented to Richard Armstrong ’46 Award Presented at Annual Princeton Baseball Banquet.” May 17, 1990.

Princeton Windrows web page. “Princeton Resident Richard Armstrong’s Song Performed in Hit Movie.” Accessed December 26, 2018. http://www.princetonwindrows.com/news/princeton-resident-richard-armstrongs-song-performed-in-hit-movie.

Photos courtesy of Bob Golon.

Notes

1 Marquis Who’s Who. “Profile Detail — Richard Stoll Armstrong.” Accessed November 5, 2018, via Ocean County (NJ) Library online resources at www.theoceancountylibrary.org.

2 Richard Stoll Armstrong, interviewed by Bob Golon. Princeton, NJ. March — June 2016. (Unpublished oral history interview recorded at the Princeton Theological Seminary)

3 J.G. Taylor Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics,” The Sporting News, October 1950, article accessed from the Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York. BA MSS 110, October 1, 2018.

4 Ibid.

5 Princeton Office of Athletic Communications. “Peters Award Presented to Richard Armstrong ’46 Award Presented at Annual Princeton Baseball Banquet.” May 17, 1990.

6 “WW II and the Navy V-12 Program.” Hobart and William Smith College Archives, online exhibits at https://hwsarchives.omeka.net. Accessed October 25, 2018.

7 Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics.”

8 Dick Armstrong, interviewed by Bob Golon, 2016.

9 “Peters Award Presented to Richard Armstrong ’46 …” May 17, 1990.

10 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 4 Folder 10.

11 Paul Lukas, “From Connie Mack to Mr. Oriole: A Conversation with Dick Armstrong,” Uni-Watch.com, accessed at https://uni-watch.com/2019/01/15/from-connie-mack-to-mr-oriole-a-conversation-with-dick-armstrong/ on January 18, 2019.

12 Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics.”

13 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 1 Folders 1-6.

14 Dick Armstrong, conversation with Bob Golon, October 5, 2018.

15 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 1 Folders 7-8.

16 Richard Stoll Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2011, 39-40.

17 Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics.”

18 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 2 Folders 2-4.

19 Dick Armstrong, conversation with Bob Golon, November 16, 2018.

20 Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics.”

21 Richard Stoll Armstrong, “Meeting of Philadelphia SABR Chapter,” Minding What Matters (blog). ca. January 2013. http://rsarm.blogspot.com.

22 Spink, “He’s Giving Young Ideas to Athletics.”

23 Dick Armstrong, conversation with Bob Golon, November 16, 2018.

24 Warren Corbett, “Connie Mack’s Less Than Graceful Exit,” The Hardball Times, February 20, 2014. Article accessed at https://www.fangraphs.com/tht/connie-macks-less-than-graceful-exit on November 27, 2018.

25 Photo caption, author unknown. Philadelphia Inquirer. July 19, 1952, p. 14.

26 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 3 Folder 9.

27 Letter from Edward D. Barker, Vice-President, W. Wallace Orr, Inc. Advertising, April 3, 1953.

28 Richard Stoll Armstrong, interviewed by Bob Golon. Princeton, NJ. March — June 2016.

29 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 2 Folder 13.

30 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, pp. 8-9.

31 Ibid., 10-11.

32 Ibid., 13.

33 Herb Heft, “Orioles’ Out-of-Town Fans Spent $5,500,000,” The Sporting News, January 12, 1955. (Article accessed from the Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110, October 1, 2018.)

34Dick Armstrong, Baltimore Baseball Club Survey, 1954. Accessed from the Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110, October 1, 2018.)

35 Ibid., 10-23.

36 “Game’s $ Value to Community Shown,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1955.

37 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 4 Folder 4.

38 Richard Stoll Armstrong, Minding What Matters blog, “Mr. Met Was Not the First M.L. Mascot!” May 4, 2012. Accessed at http://rsarm.blogspot.com.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

41 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, pp. 16-17.

42 Ibid., 19.

43 Ibid., 26.

44 Ibid., 20.

45 Ibid., 69-70.

46 Ibid., 49.

47 Ibid., 50.

48 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 4 Folder 6.

49 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, p. 75.

50 Ibid., 83-87.

51 Ibid., 108.

52 Armstrong Collection, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY. BA MSS 110. Box 3 Folder 10.

53 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called, p. 77.

54 Richard Stoll Armstrong, interviewed by Bob Golon. Princeton, NJ. March — June 2016.

55 Armstrong, A Sense of Being Called. (book jacket endorsement)

56 Richard Stoll Armstrong, interviewed by Bob Golon. Princeton, NJ. March — June 2016.

57 Ibid.

58 “Princeton Resident Richard Armstrong’s song performed in hit movie.” From the Princeton Windrows web page accessed at http://www.princetonwindrows.com/news/princeton-resident-richard-armstrongs-song-performed-in-hit-movie/ on December 26, 2018.

59 Richard Stoll Armstrong, interviewed by Bob Golon. Princeton, NJ. March — June 2016.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.

62 Richard Stoll Armstrong, Minding What Matters blog, “My First and Last Pitch,” August 12, 2014. Accessed at http://rsarm.blogspot.com.

63 Gates, Jim. ‘Dick Armstrong.’ Email. November 13, 2018.

64 Rev. Elsie Armstrong Rhodes, interviewed by Bob Golon. Cooperstown, New York, October 1, 2018.

Full Name

Richard Stoll Armstrong

Born

March 29, 1924 at Baltimore, MD (US)

Died

March 11, 2019 at Princeton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.