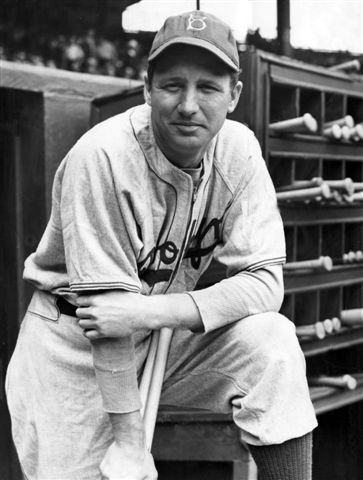

Dixie Walker

During Dixie Walker’s playing days, he won a batting championship and a runs-batted-in title, and he played in two World Series and four All-Star Games. Yet modern-day fans remember him mostly for the charge that he was the player most responsible for trying to keep Jackie Robinson from joining the Brooklyn Dodgers.

During Dixie Walker’s playing days, he won a batting championship and a runs-batted-in title, and he played in two World Series and four All-Star Games. Yet modern-day fans remember him mostly for the charge that he was the player most responsible for trying to keep Jackie Robinson from joining the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Dating from his major-league debut as a twenty-year-old in 1931, Walker’s abilities were so apparent as to make many in the media call him the eventual successor to Ruth in the Yankees outfield. A series of recurring injuries throughout Walker’s eight-year American League career prevented that from ever happening. In May 1936, the Yanks sold him to the Chicago White Sox to clear a roster spot for the man who truly would be the Babe’s successor—Joe DiMaggio.

Overall, the left-handed-hitting Walker batted .306 and accumulated 2,064 hits during his eighteen-year big-league career. Tall and lean, at six feet one and 180 pounds, he was a solid hitter, a fine defensive player with an excellent throwing arm, and in his early days, among the fastest players in the game.

Of Scotch-Irish descent, Fred Walker was born in a log cabin in Villa Rica, Georgia, on September 24, 1910. Villa Rica was a small railroad and factory town about 35 miles west of Atlanta. He was the first child born to Ewart and Flossie (Vaughn) Walker. Ewart, also known as Dixie, was in his second season as a right-handed pitcher for the Washington Senators when Fred was born. In four seasons with Washington, the original Dixie Walker won twenty-five games and lost thirty-one. After his major-league career ended, he returned to the minor leagues, where he had a long career as a manager. Ewart’s younger brother, Ernie, also reached the major leagues, as an outfielder for the St. Louis Browns between 1913 and 1915.

Young Fred left school at the age of 15 to take a job with the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company, a Birmingham steel mill, working at the open hearth. It was hot, backbreaking work, and Walker never forgot it. As the son and nephew of major leaguers, Dixie, like his younger brother Harry, also a future National League batting champion, spent his whole life in baseball. He began his professional career in 1928 as an outfielder-third baseman, splitting the season among Greensboro (North Carolina) of the Piedmont League, Albany (Georgia) of the Southeastern League, and Gulfport (Mississippi) of the Cotton States League. In 1929 Walker was back in the Class D Cotton States League, where he batted .318 for the Vicksburg (Mississippi) Hill Billies. That earned him a promotion to the Class B Greenville (South Carolina) Spinners of the South Atlantic Association in 1930. Walker was batting a sensational .401 at midseason, when the New York Yankees purchased his contract and assigned him to Jersey City of the International League. He continued his steady hitting, compiling a .335 mark in 83 games with the Skeeters. Showing power and speed, he had a combined 104 RBI and 32 stolen bases for the season.

In 1931 the Yankees invited the twenty-year-old Walker to spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he impressed everyone with his batting, fielding, and throwing. He started the year with the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association; however, two weeks into the season, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy found himself short of outfielders due to injuries, and recalled Walker.

Dixie made his major-league debut at Washington on April 28, 1931, in a fourteen-inning game called because of darkness. Walker had three hits in seven at-bats, including his first big-league hit, a single off Sam Jones. Shortly thereafter, sidelined outfielders Babe Ruth, Sammy Byrd, and Myril Hoag returned, and Walker went back to Toledo.

When the Mud Hens hit a financial crisis in midsummer, they asked the Yankees for salary relief for Walker and shortstop prospect Bill Werber. The Yanks responded on July 8, sending Walker back to Jersey City. He spent the rest of the 1931 season in the International League. Playing for Jersey City and Toronto, he batted a combined .352, third best in the league.

In 1932 Walker went to spring training with the International League’s Newark Bears, a club that Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert had purchased the previous November. He spent the entire season with the Bears, batting .350 with 105 RBI, and was voted to the International League All-Star team.

Ruth, Earle Combs, and Ben Chapman would be the Yankees’ starting outfield in 1933, with Sammy Byrd slated for one of the two reserve slots. McCarthy chose Walker for the other. A feature story in the May 4, 1933, edition of The Sporting News said the Yanks thought Walker could be next in line for a full-time spot in the outfield, maybe as the eventual replacement for Ruth. In June, when the thirty-four-year-old Combs slumped at bat, Walker replaced him in center field. Playing in ninety-eight games as a rookie, he batted .274 with fifteen home runs, the most home runs he would ever hit in the big leagues. The Sporting News selected him as the right fielder on its unofficial American League rookie team for 1933.

Walker was also involved in two of the more memorable moments of that season, four days apart in late-April games against the Washington Senators. In a game at Griffith Stadium on April 25, Chapman slid very hard into Senators second baseman Buddy Myer, knocking him over. When Myer retaliated by kicking Chapman, a full-scale battle broke out between the two teams. After the umpires ejected Chapman and Myer, Washington pitcher Earl Whitehill cursed at Chapman as he left the field, Chapman responded by punching Whitehill in the face, setting off an even rowdier battle. Walker, Chapman’s friend, neighbor in Birmingham and his Yankee roommate, came rushing out of the dugout to help. A large group of angry Washington fans surrounded Walker, who was finally rescued by teammates Tony Lazzeri, Lefty Gomez, and Bill Dickey. Walker was ejected and several fans arrested before order was finally restored.

Four days later, the Yanks were trailing the Senators, 6–3, in the bottom of the ninth. Lou Gehrig was on second base and Walker on first with no outs when Tony Lazzeri hit a drive into right-center field. Right fielder Goose Goslin got to the ball quickly and relayed it to shortstop Joe Cronin, who threw it to catcher Luke Sewell. With ball in hand, Sewell first tagged the slow-footed Gehrig, and then tagged Walker, who was only steps behind Gehrig, to complete the unusual double play.

Walker hit his first big-league home run at Boston’s Fenway Park off Johnny Welch on June 11, 1933. By late June, the rookie had gradually begun to take over the center-field job from Combs. But after tearing tendons in his right shoulder in a game on September 19, he sat out the rest of the season, except for a brief appearance on the last day.

At spring training in 1934, almost everyone connected to baseball was again predicting stardom for Walker. However, he developed a sore arm in the spring and did little more than pinch-hit and pinch-run all season. In mid-August, the Yanks took Dixie off the roster, and put him on the voluntarily retired list.

By March of 1935 Walker was throwing from the outfield with apparent ease. But during an exhibition game at West Point in April, he dislocated his right (throwing) shoulder while sliding into second. The injury put him out indefinitely, and it would take several years before he regained full throwing ability. He played a few games in late May and early June, before the Yankees sent him back to Newark. Dixie played In eighty-nine games for the Bears, batting .293, with seventeen home runs. In what should have been two prime seasons with the Yankees (1934-35), Walker had appeared in just twenty-five games for them.

On May 1, 1936, the Yankees sold Walker to the Chicago White Sox’s for a reported $20,000. The next day, before the White Sox left New York, Walker pushed up his wedding plans and married native New Yorker Estelle Shea, a young woman who worked at the prestigious Music Corporation of America talent agency.

Although he had to leave the pennant-contending Yankees for the White Sox, Walker was glad to have a chance to play every day. He started poorly for Chicago, with only one hit in his first few games before collecting five in a 19–6 shellacking of the St. Louis Browns on May 11. But on May 23, Walker again dislocated his right shoulder. A collision with Browns first baseman Jim Bottomley sidelined him for three months. In all he played just twenty-six games for Chicago, which along with the six he played for the Yankees added up to his third consecutive injury-shortened season.

That winter he had surgery on the shoulder that involved the refastening of tendons. After resting the arm all winter, Dixie was in right field and batting third on Opening Day against the Browns. Free from any major injury for the first time as a big leaguer, Walker played in all 154 games in 1937 for the White Sox. He batted .302 with ninety-five runs batted in, and his sixteen triples tied him for the American League lead.

Nevertheless, on December 2, 1937, Chicago traded Walker, along with pitcher Vern Kennedy and infielder Tony Piet, to the Detroit Tigers for outfielder Gerald “Gee” Walker (no relation), third baseman Marv Owen, and minor-league catcher Mike Tresh. The deal was extremely unpopular in Detroit, where fans reacted angrily to the trading away of Gee Walker, one of the best-liked players ever to wear a Tigers’ uniform.

As the replacement for 1the very popular Gee Walker, Dixie had a difficult time in Detroit. Although he batted .308 in 1938, and was playing a sensational left field, the hometown fans continued to boo him. In late July 1939, Walker, who had tied the American League record by scoring five runs in a game on April 30, was batting .305. But torn knee ligaments had limited his playing time, leading the Tigers to put him on waivers. Despite his many injuries, Walker had compiled a .295 batting average during his eight years in the American League.

On July 24, 1939, Brooklyn’s Larry MacPhail purchased Walker’s contract from the Tigers. Thus began the transformation of Dixie Walker from one of the most unpopular players ever to wear a Detroit uniform, to perhaps the most popular one ever to wear a Brooklyn uniform. The Dodgers had not won a pennant since 1920, but under their new owner, MacPhail, and first-year manager, Leo Durocher, the team was very much on the upswing.

Dixie made his first start for Brooklyn on July 27, 1939, after striking out as a pinch hitter two days earlier. Over the remainder of the 1939 season, he batted .280, while establishing himself as the team’s center fielder. The addition of rookies Pee Wee Reese and Pete Reiser and a trade for Joe Medwick helped the Dodgers climb to second place in 1940. Walker led the club in batting (.308) and doubles (37), while finishing sixth in the voting for the National League’s Most Valuable Player. He was also quickly becoming a favorite of the Brooklyn fans. A .435 batting average against the hated New York Giants in 1940 helped fuel his popularity, and would eventually earn him the title of “The People’s Choice.” However, the year was not without heartbreak for Dixie and for Estelle. On May 23, their four-month-old daughter, Mary Ann, died of pneumonia.

Before the start of spring training in 1941, the Dodgers signed former Pittsburgh Pirates great Paul Waner. The future Hall of Famer played well in spring training, leading Durocher to announce that the thirty-eight-year-old Waner, not Walker, would be his opening day right fielder. Five thousand outraged Brooklyn fans signed a petition supporting Walker, but Durocher, backed by MacPhail, refused to yield. However when Waner got off to an atrocious start, the Dodgers released him and reinstalled Walker in right, where, with occasional exceptions, he would remain a fixture for the next seven years.

A trade for second baseman Billy Herman on May 6 fortified an already strong Dodger infield that had Dolph Camilli at first base, Pee Wee Reese at shortstop, and Harry Lavagetto at third. Mickey Owen caught a pitching staff that included Whit Wyatt, Hugh Casey, and newly obtained Kirby Higbe. The blossoming of Reese and Reiser, combined with the excellent group of veterans acquired by MacPhail and Durocher, turned the Dodgers into winners. They captured their first pennant in twenty-one years, finishing two and a half games ahead of the St. Louis Cardinals. In an all-New York City World Series, they lost to the Yankees in five games. Walker was tenth in the MVP voting, earning his place on the list with a .311 batting average, eighth best in the league, along with placing in the top ten in numerous other offensive categories.

When the Dodgers opened a ten-game lead on St. Louis in early August 1942, they appeared on their way to a repeat pennant and another shot at the Yankees. But the Cardinals mounted one of the great comebacks ever, to edge Brooklyn by two games. MacPhail had warned the club that they were losing ground and predicted that St. Louis would pass them, a prediction that several players, primarily Walker, had ridiculed. An ankle injury in late April and a leg injury in June, the latter suffered in an on-field brawl with the Cardinals, limited Walker to 118 games in 1942. He batted .290—his only sub-.300 season as a Dodger, and the only one in which he failed to get any MVP votes.

By 1943 all of baseball was losing players to the war; the Dodgers, minus Reese, Reiser, and Casey, dropped to third place. Walker bounced back from a subpar 1942 with a solid season, finishing in the top ten in batting, runs, hits, and doubles, and appeared in his first All-Star Game.

The year was not without controversy in Brooklyn. Few years were. On July 10 the Dodgers almost to a man refused to take the field for a game against the visiting Pirates. Arky Vaughan had organized the boycott to protest manager Durocher’s three-game suspension of pitcher Bobo Newsom for insubordination. At the last minute, GM Branch Rickey persuaded Vaughan and the others to play. Durocher was particularly upset with Walker for siding with Vaughan and threatened to trade him.

Although baseball injuries to his knee and shoulder exempted him from military service, Dixie did a lot to help in other ways. During the off-season he worked for the Sperry Gyroscope Company on Long Island, and also served as their athletic director. In December, Walker was part of a USO tour group of players who visited American servicemen in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.

As with all the other big-league teams, the Dodgers 1944 roster was composed mostly of aging veterans, fuzzy-cheeked kids, and 4-Fs. In all, it was a disastrous season for Brooklyn, the worst in Durocher’s tenure with the club. The Dodgers finished in seventh place, forty-two games behind the Cardinals, who captured their third consecutive pennant.

Meanwhile Walker, at the age of thirty-three, had the best season of his career, winning the National League batting championship, with a .357 average. In addition, he drove in ninety-one runs, finished in the top five in hits, doubles, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and total bases, and was the starting right fielder in the All-Star Game. Walker, the father of three, also received a notable off-the-field honor. The National Father’s Day Committee voted him the “Sports Father of the Year.”

Walker’s outstanding season earned him a close third-place finish in balloting for the Most Valuable Player Award. The Sporting News placed him on its Major League All-Star team, and the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America honored him with the prestigious Sid Mercer Award as the Player of the Year.

In November 1944 Walker again joined a group of players and umpires that visited various theaters of operation as part of a USO-sponsored program to entertain the troops. With even more players lost to the military, talent for the 1945 season was at an all-time low. Walker did not repeat as batting champion—he hit an even .300—but he did win the runs-batted-in title with 124.

The end of the war made the competition for roster spots in 1946 more competitive than ever. Walker ultimately kept his job and joined rookie Carl Furillo and the returning Pete Reiser as outfield starters. In his first at bat of the spring, Dixie hit a bases-loaded triple against the Montreal Royals at Daytona Beach. The game was among the most significant in spring training history, with ramifications that affected not only baseball, but also the course of American history.

Playing second base for Montreal, Brooklyn’s top farm team, was Jackie Robinson, a black man signed by Rickey during the off-season. The game marked the first appearance of an integrated team in Organized Baseball in the 20th century. The teams played several times, without incident. “As long as he’s not on the Dodgers, I’m not worried,” said Walker. Robinson remained with the Royals in 1946, where he won the International League batting championship.

After a season-long battle with a surprising Dodgers team, the Cardinals captured the pennant in the first postseason playoff in major-league history. Walker, Brooklyn’s best player, had another outstanding season. His .319 batting average was third best in the National League, and his 116 runs batted in were second best. Though now an “old man” by baseball standards, the thirty-five-year-old Walker had nine triples and a career-high fourteen stolen bases. He was the starting right fielder for the National League in the All-Star Game, and he finished second to Stan Musial in the vote for the league’s Most Valuable Player.

Although Dixie Walker was a gentle man off the field, he was a fiery competitor on it. That trait had led to his involvement in the 1933 battle with the Washington Senators. In 1946, it landed him in a couple of melees with the Chicago Cubs, centering on another Southern teammate, Eddie Stanky, and Cubs shortstop Lennie Merullo.

A fight broke out between the two in the tenth inning of a game at Ebbets Field on May 22 when Merullo slid into second baseman Stanky with his spikes high. The two men then started punching each other, precipitating a brawl between the two teams. The next day policemen, anticipating more trouble, sat along the dugouts of both clubs. Yet despite their vigilance, a pregame fight broke out between Walker and Merullo in the batting cage. The fight cost Walker, Merullo, Pee Wee Reese, and Cubs first baseman Phil Cavarretta, who punched Leo Durocher, $650. Additionally, Walker, Merullo and Cubs coach Red Smith all received brief suspensions.

When the Major League Players Association was set up in 1946, Walker was chosen the Brooklyn representative, as well as the overall National League representative. New York Yankees pitcher Johnny Murphy was chosen as the American League representative. Their primary goal was the institution of a pension plan for major-league players. That goal was achieved early in 1947. Commissioner Happy Chandler announced a plan under which players with five years’ experience would receive $50 a month at age fifty, and $10 a month more for each of the next five years.

By the end of the 1946 season Walker was, in the words of Dodger broadcaster Red Barber, the most popular player in Brooklyn history. That would begin to change the following spring. On April 10, 1947, during an exhibition game against the Montreal Royals at Ebbets Field, the Dodgers announced that they had purchased the contract of Jackie Robinson and that “he will report immediately.” No one knew what effect the addition of the first black man to play in the major leagues in the twentieth century would have on the Dodgers. To complicate the situation further, the announcement came one day after Commissioner Chandler had suspended manager Leo Durocher for the season.

On opening day at Ebbets Field, interim manager Clyde Sukeforth’s lineup card had Robinson at first base and Walker in right field. Robinson and Walker were in those same positions when Burt Shotton took over as manager a few days later, and, despite rumors that Walker would be traded, they remained there for the rest of the season.

The relationship between Dixie Walker and Jackie Robinson is, of course, one that transcends the playing field and is more a reflection of race relations in America, especially as they were in 1947. Although Walker was a lifelong Southerner, he did not “hate” Robinson; however, there is no doubt that he did not want Robinson, or any other black man, as a teammate. Announcer Red Barber, himself a Southerner, has written of the problem he had in merely broadcasting a game in which Robinson took part.

Walker, who had a hardware store in Birmingham, feared his playing with a black man would hurt his business. Yet despite his distaste for integration, Walker never went out of his way to be unpleasant to Robinson, who later described him as a man of innate fairness.

Robinson had a most difficult season, enduring racial insults from players and fans. Perhaps the worst insults came from Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman, Walker’s good friend. With incredible courage and self-restraint, Robinson not only showed he “belonged,” he was honored with the major leagues’ Rookie of the Year Award. Along with Walker, who batted .306 and had a team-leading ninety-four runs batted in, this baseball “odd couple” helped lead the Dodgers to a pennant. After the season, Walker paid tribute to his teammate. He said only Bruce Edwards had done more to put the Dodgers on top. He agreed that Robinson was very much the excellent ballplayer Branch Rickey had claimed he would be.

Walker and Robinson had made the best of a very awkward situation. Robinson would go out of his way to avoid putting Walker in a situation that might be perceived in Alabama as an acceptance of integration, while later acknowledging how grateful he was for a batting tip Walker gave him when he was struggling at the plate.

Walker had grown up believing blacks did not have what it takes to play at the major-league level. Robinson’s athletic ability and the mental and emotional strength he exhibited in withstanding all that was thrown at him convinced Walker otherwise. “A person learns, and you begin to change with the times,” Dixie would later say. The two never became friends, but Walker continued to praise Robinson’s abilities and character for as long as he lived.

Performing under difficult personal circumstances, Walker had continued to produce and had done nothing to disrupt the team’s drive to the pennant. In the voting for the Most Valuable Player that year, he received one first-place vote, but, strangely, the other twenty-three writers left him off the ballot.

The 1947 World Series was one of the most thrilling ever, but the result was another loss to the Yankees, this one in seven games. Walker’s groundout to the second baseman leading off the ninth inning of Game Seven turned out to be his last at-bat in a Brooklyn uniform.

During spring training Walker had been among a group of Dodgers players who had asked the Dodgers not to add Robinson to the team. When that failed, he took what he believed to be the best way out of his integration dilemma. He wrote a letter to Branch Rickey in which he asked Rickey to trade him as the best solution for all concerned. Rickey tried, somewhat reluctantly, not wanting to lose his most productive hitter. Following the season Rickey offered Walker a chance to stay in the organization as the manager of the American Association’s St. Paul Saints at a salary of $15,000. Or, he would send him to Pittsburgh, where Walker could make more money.

Walker wanted to manage eventually, but not yet; nor did he want his salary reduced to $15,000. So Rickey sold him to Pittsburgh for one dollar, with the proviso that the Pirates add the $10,000 waiver price to Dixie’s 1948 contract. Rickey chose to not make this public, instead announcing that Walker was part of the big trade that brought Preacher Roe and Billy Cox to Brooklyn

With Pittsburgh in 1948, Walker topped the .300 mark for the tenth time in twelve seasons, helping the Pirates climb from last place to fourth. Meanwhile, the Brooklyn fans showed they had not forgotten him. On the Pirates’ first visit to Ebbets Field, they staged a Dixie Walker Day that included, among other gifts, a new car for their longtime favorite.

By 1949, Walker’s playing career had reached its end. He played in just eighty-eight contests—though he led the National League with thirteen pinch hits. He hit his only home run, the final one of his career, on July 20 off Ralph Branca as a pinch-hitter. Appropriately, it came at Ebbets Field, sailing over the right-field wall and landing on Bedford Avenue.

The Pirates released Walker after the season and he began immediately looking for a managerial job, at either the major-league or high minor-league level. On December 5, 1949, he signed to replace Cliff Dapper as manager of the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. In his first season, 1950, Walker led the Crackers to the regular-season pennant. Dixie returned to Atlanta in 1951, where his team finished sixth before rising to second in 1952.

The St. Louis Cardinals added Walker to their coaching staff in 1953, but in late July asked him to take over the Houston team in the Texas League. Walker stayed with Houston through 1954, but then spent the next five years managing in the International League. In 1955 and ’56, he led the Rochester Red Wings and from 1957 through 1959, the Toronto Maple Leafs.

The Braves, now in Milwaukee, employed Walker as a scout from 1960 to 1962. Bobby Bragan, his onetime Dodgers teammate, took over as the Braves’ manager in 1963 and added Walker to his coaching staff, primarily as a hitting instructor. After the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1966, they put Dixie in charge of their scouting in the Southeast.

When Los Angeles Dodgers batting coach Duke Snider left in 1968, the Dodgers replaced him with Walker. At training camp in 1969, Walter Alston praised Walker for his work with the team’s younger players. The Dodgers kept Walker with the club all season as batting coach, a move highly praised by the players. Over the years, Walker helped improve the batting of countless Dodgers. Among the Los Angeles players who praised him for his help with their batting were African American stars Dusty Baker, Jim Wynn, and Maury Wills.

Walker’s rehabilitation, at least in the Dodgers family, was complete. At spring training in 1971, Walter O’Malley presented him with a silver bat worth $2,500, emblematic of his 1944 batting championship. O’Malley also included Dixie in his personal all-time Dodgers’ outfield, along with Duke Snider and Carl Furillo.

After the 1974 season, the sixty-four-year-old Walker stepped down as the Dodgers’ hitting coach, saying he now preferred to work with the team’s minor leaguers. He retired from baseball after the 1976 season and returned to Birmingham.

Dixie Walker died of colon cancer on May 17, 1982, at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Birmingham and is buried in that city’s Elmwood Cemetery. He was survived by Estelle, who lived for another twenty years, daughters Mary Ann and Susan, and son Stephen, born in 1954. Two of his sons predeceased him. Fred Jr. died in a scuba diving accident in 1971, and Sean of an accidental gunshot wound in 1975.

Sources

Barber, Red. 1947—When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1982.

Barber, Red and Robert Creamer. Rhubarb in the Catbird Seat. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1968.

Creamer, Robert W. Baseball in ‘41. New York: The Penguin Group. 1991.

Campbell, Gordon. Famous American Athletes of Today (Ninth Series). Boston: L. C. Page And Company, 1945.

Durocher, Leo with Ed Linn. Nice Guys Finish Last. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975.

Eig, Jonathan. Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Goldstein, Richard. Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, Inc. 1980.

Marzano, Rudy. The Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1940s: How Robinson, MacPhail, Reiser and Rickey Changed Baseball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2005.

McGee, Robert. The Greatest Ballpark Ever: Ebbets Field and the Story of the Brooklyn Dodgers. New Brunswick, NJ: Rivergate Books, 2005.

Ahrens, Art. “The Old Brawl Game,” The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research, No. 23, 2003, pages 3-6.

Robinson, Jackie, as told to Alfred Duckett. I Never Had it Made. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972.

Simon, Scott. Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002.

Barber, Red. “Leadoff Man,” The New Republic, July 4, 1983.

Boren, Stephen D. and Thomas Boren, “The 1942 Pennant Race,” The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research, No. 15, 1995, pages 133-135.

Broeg, Bob. “The ’42 Cardinals,” Sport, July 1963, p. 40 (7).

Gaven, Michael. “What a Load of Rhubarb,” Baseball Digest, February 1958, p. 51 (12).

Graham, Jr. Frank. “Greatest Fight on a Ballfield,” Baseball Digest, June 1953, p. 45 (2).

Kavanagh, Jack. “Dixie Walker,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, No. 22, 1993, pages 80-83.

MacPhail, Lee. “Year to Remember Especially in Brooklyn,” The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research, No. 11, 1991, pages 41-43.

McGowen, Roscoe. “Boss of Bums But Not Bum Boss,” Baseball Magazine, August 1947, p. 307 (4).

Panaccio, Tim. “How it Was During the War Years,” Baseball Digest, January 1977, p. 68 (3).

Powell, Larry. “Jackie Robinson and Dixie Walker: Myths of the Southern Baseball Player,” Southern Cultures, Summer, 2002, pages 56-70.

Tiller, Guy. “Prospect for Majors: Dixie Walker,” Baseball Digest, October 1950, p. 85 (2).

Wise, Bill. “Dixie Does All Right,” Sport Pix, June 1949. p. 8 (5).

Bailey, Judson, “New Players Put Brooklyn There—MacPhail,” Atlanta Constitution, August 22, 1941.

Berkow, Ira, “Dixie Walker Remembers,” New York Times, December 10, 1981.

Berkow, Ira, “Dixie Walker: You Associate With Blacks Till You Know Them,” Burlington NorthCarolina Times-News, March 29, 1972.

Berkow, Ira “Ice Water in the Veins,” New York Times, April 10, 1987.

Broeg, Bob. “Backward, Turn Backward Oh Time . . . ,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 23, 1972.

Broeg, Bob. “Fine Alabama Contribution to Baseball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 21, 1949.

Bromberg, Lester, “Dodger Fans: Dixie’s on Job And Will Be Set for Opener,” New York World Telegram, February 22, 1947.

Burr, Harold C, “Dixie Walker’s More Than Man-of-Week to Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 7, 1946.

Daniel, Dan. “Dixie Bids for Yank Job,” New York World Telegram, April 5, 1935.

Daniel, Dan. “Dixie Walker Ascribes Added Power to Change in Bats,” New York World-Telegram, July 8, 1946.

Dunnell, Milt, “Dixie Lived Down the Racist Image of Robinson Case,” Toronto Star, May 19, 1982.

Goldpaper, Sam, “Dixie Walker, Dodger Star of the 1940’s, Dead at 71,” New York Times, May 18, 1982.

Good, Charlie. “League Batting Leader Joins the Toronto Club,” Toronto Daily Star, August 28, 1931

Greene, Sam, “Detroit Fans Deride Cochrane For Swapping Walker To Dykes,” Sporting News, December 9, 1937.

Kirksey, George, “MacPhail’s Spending Due To Net Dodger Flag,” Atlanta Constitution, December 22, 1940.

McGowen, Roscoe. “Dodgers Revolt Against Durocher, Then Play and Win Game, 23-6,” New York Times, July 11, 1943.

Rice, Robert, “The Artful Dodger,” PM, August 8, 1943.

Roeder, Bill. Walker-Merullo Bout Seen Top Diamond Brawl,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, July 26, 1954.

Vaughan, Irving, “Baseball Got Dixie Walker in Steel Mill, Also Got Him Out,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 14, 1937.

Wolf, Bob. “Dixie Adds Dynamite to Braves’ Bats,” Sporting News, December 26, 1964.

Young, Fay, “End of Baseball’s Jim Crow Seen With Signing of Jackie Robinson,” Chicago Defender, November 3, 1945.

Email conversations by author with Stephen Walker.

Full Name

Fred Walker

Born

September 24, 1910 at Villa Rica, GA (USA)

Died

May 17, 1982 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.