Dobie Moore

Walter “Dobie” Moore was one of the greatest shortstops in Black baseball history. Nicknamed “The Black Cat,” he was a powerful hitter and gifted fielder. He began his career playing for the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry baseball team (a squad that produced more than a dozen Negro League players in the years surrounding World War I) before joining the Kansas City Monarchs. In 1926, his career abruptly ended at the age of 29 as the result of an incident clouded with mystery.

Walter “Dobie” Moore was one of the greatest shortstops in Black baseball history. Nicknamed “The Black Cat,” he was a powerful hitter and gifted fielder. He began his career playing for the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry baseball team (a squad that produced more than a dozen Negro League players in the years surrounding World War I) before joining the Kansas City Monarchs. In 1926, his career abruptly ended at the age of 29 as the result of an incident clouded with mystery.

Walter Moore (possibly Walter Lewis Moore) was born February 8, 1896, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Waddie Moore and Julia Drummond. Moore had five siblings (though some may have been half-siblings). Walter was the oldest, and he had a younger brother, Allen T. “Pete” Moore, who played at least three games for the Birmingham Black Barons in 1929. Standing about 5-foot-10 and weighing in at around 180 pounds (with some sources listing him as high as 230 pounds), the right-handed Moore was “built like a locomotive, with massive chest and arms.”1

Very little information is available about Moore’s upbringing beyond the fact that he received a third-grade education.2 Multiple sources referred to Moore as “illiterate,” but a 1925 Pittsburgh Courier story documents how he nearly missed the team bus because he was fully focused on a magazine article.3 By 1914 he was on the ballfield catching for the local Atlanta Stars.4 On May 11, 1915, Moore enlisted in the Army at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia. Like some of his future Army and Monarchs teammates, he gave an incorrect year of birth when registering (1893).5 Moore departed Fort Oglethorpe for Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri.6 From there he joined the 25th Infantry Regiment, already stationed at Schofield Barracks on the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

The 25th Infantry Regiment was one of four all-Black US Army units formed in 1866 and collectively known as the “Buffalo Soldiers.” The unit established its baseball team in 1893 and arrived in Oahu in 1913 (where they were called the “Wrecking Crew” or, more commonly, simply the “Wreckers”). By the time Moore joined the team, they were considered one of the top teams in the country, Black or White. The Negro National League had not yet been founded, and playing baseball in the Army was a steady and predictable paycheck for a Black ballplayer.

While on the way to Hawaii, he met William “Big C” Johnson in San Francisco. Johnson was also heading to Oahu to join the 25th Infantry. The two were in Company A together and later played on the baseball diamond for the regiment team.

Once he arrived on the island, Moore immediately joined the regiment team. The team already featured several of his future Kansas City Monarchs teammates: pitcher/outfielder Wilber “Bullet” Rogan, outfielder Oscar “Heavy” Johnson, first baseman Lemuel Hawkins, and second baseman Bob Fagan. Moore made his first documented appearance for the Wreckers on February 22, when he started at third base and batted eighth against the traveling Olympic Club of San Francisco.7 Moore started again three days later against the Chinese Travelers and collected his first hit for the regiment team.8 The following day, Moore tripled in the final game of the Olympics’ tour, as the Wreckers won a dramatic match 2-1 on a walk-off home run by Oscar Johnson.9

In all, Moore played in 34 of the 39 games for which box scores have been found in 1916—all of them at third base. He hit .234 for the year with a pair of doubles and four triples.10 While he wasn’t the immediate offensive sensation teammates Rogan and Johnson were, he cemented his role at the hot corner in his first season with the team.

Moore’s performance dramatically improved in 1917, as he batted .286 with a .466 slugging percentage (thanks to four doubles, seven triples, and two home runs) in 33 games (out of 33 known box scores). He again exclusively played third base, except for one late-game switch to shortstop. He also improved his fielding percentage from .802 to .927.11

In 1918, Moore was named a Service League All Star by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Sports editor Banty Given noted, “Moore is by far the best third-sacker in the league.”12 Moore batted .277 with a .468 slugging percentage in the 12 box scores located for the Wreckers’ 1918 season. The team’s season was cut short, as they were transferred to Camp Stephen D. Little in Nogales, Arizona, in August. Overall, in 79 games played in Hawaii, Moore hit .265 with a .415 slugging percentage. He clubbed eight doubles, 13 triples, and three home runs.13

In Nogales, Moore and the 25th Infantry were assigned to guard a new two-mile barbed wire barrier constructed on the United States-Mexico border. Following the Battle of Ambos Nogales, this was the first permanent border wall constructed between the two countries. The conflict broke out while the unit was traveling to the mainland.14 For the remainder of the year, the team focused much more on their military duties than on baseball.

Unfortunately, no box scores are available for the 1919 season, but Moore became the team’s starting shortstop after J. “Saki” Smith, who had patrolled the position since 1915, was discharged.15 Moore himself was discharged on June 29, but he immediately reenlisted.16 In July, Moore competed in the running broad jump and 440-yard relay at an all-Army track meet.17 He spent years running track for the 25th Infantry, reportedly also playing wide receiver on the unit’s football team.18 Also during the summer, Moore joined Army teammates Rogan, Johnson, and pitcher George Jasper on the integrated Nogales Nationals baseball team.19

In November, Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Casey Stengel brought an all-star team of major- and minor-league players to Nogales for a series against the Wreckers at Camp Little. En route to Arizona, Stengel’s squad was undefeated, even taking a pair of victories against Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants (who finished first in the Negro National League the next year).20 Moore and Johnson were available for the series, but several prominent players such as Rogan and Hawkins were not.21

The Wreckers took the first game, 5-4. Moore was the “sensation of the afternoon’s playing,” as he crushed a home run, making his way around the bases before the ball could be retrieved. Moore hit a grand slam in the second game, a losing effort by a 14-11 score. The 25th Infantry won the third and deciding game, 8-6. Two more games were later added to the series, but they received much less coverage. Each team won a game, giving the Wreckers three wins in five.22

Stengel, a Kansas City native, has been credited with discovering five of the players from the 25th Infantry who later joined the Kansas City Monarchs: Rogan, Moore, Johnson, Hawkins, and Fagan. However, Rogan and Hawkins did not play in the series. It is certainly possible that Stengel is the one who recommended Moore, Johnson, and Fagan to Monarchs owner J.L. Wilkinson.23 Moore, Rogan, Hawkins, and Fagan joined the Monarchs in the summer of 1920, possibly after paying their way out of the service.24 Johnson followed two years later.

“Dobie” (likely a variation of the term “doughboy,” slang for an infantry soldier)25 made his debut with the Monarchs on July 3 against the St. Louis Giants. He collected a single and a walk in five trips to the plate. His first home run, a grand slam, came August 18 against the Detroit Stars.26 Overall, he played 48 games against top teams and batted .332 with a .380 on-base percentage and .458 slugging percentage. The Monarchs finished second behind Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. The Kansas City Sun named him to their All-Negro League team.27 Monarchs manager José Méndez worked tirelessly with Moore after the season to shore up his defensive skills.28 The hard work paid immediate dividends, as Moore became perhaps the top all-round shortstop in the game (Black or White).

In the winter of 1920-21, Moore played for the Los Angeles White Sox in the integrated California Winter League. The league included players from the American, National, and Pacific Coast Leagues as well as the Negro Leagues. The White Sox were an all-Black team in the otherwise all-White league and featured many Kansas City Monarchs. The league’s top four hitters were all members of the Monarchs: Rogan (.368), Moore (.331), Hurley McNair (.311), and Fagan (.302). Moore led the league in games, at-bats, and hits, and tied for the lead in triples with McNair, as the White Sox won the pennant with a 22-15-2 record.29

In 1921, Moore hit .324 with increased power (seven triples and eight home runs in 64 games) to go along with his improved defense. The Monarchs again finished one spot behind the pennant-winning Chicago American Giants. After the season, the Monarchs faced the Kansas City Blues of the Class AA American Association in an eight-game series, losing five of the games.30 Moore missed the series with an injury.31 Again in the California Winter League that offseason, Moore played for the Colored All-Stars. The team won the pennant with a 25-15-1 record, but Moore dipped to a .275 batting average.32

That slump did not carry over to the Negro National League, as Moore had his best season to date. He hit .386 with seven home runs and doubled his stolen base tally to 16. Moore’s increased production and the arrival of Heavy Johnson propelled the Monarchs to their first of five consecutive first-place finishes. The Monarchs played another postseason series against the Blues and this time – with a healthy Moore – they won five of six games. They followed that with an exhibition matchup against the traveling Babe Ruth All-Stars. Moore collected a single and a triple, as the Monarchs prevailed, 10-5.33

Moore did not play in California over the winter of 1922-23. In 1923, he finished second in batting (.365) on the Monarchs behind the Triple Crown-winning Johnson. On September 5, Moore married Frances Davis.34

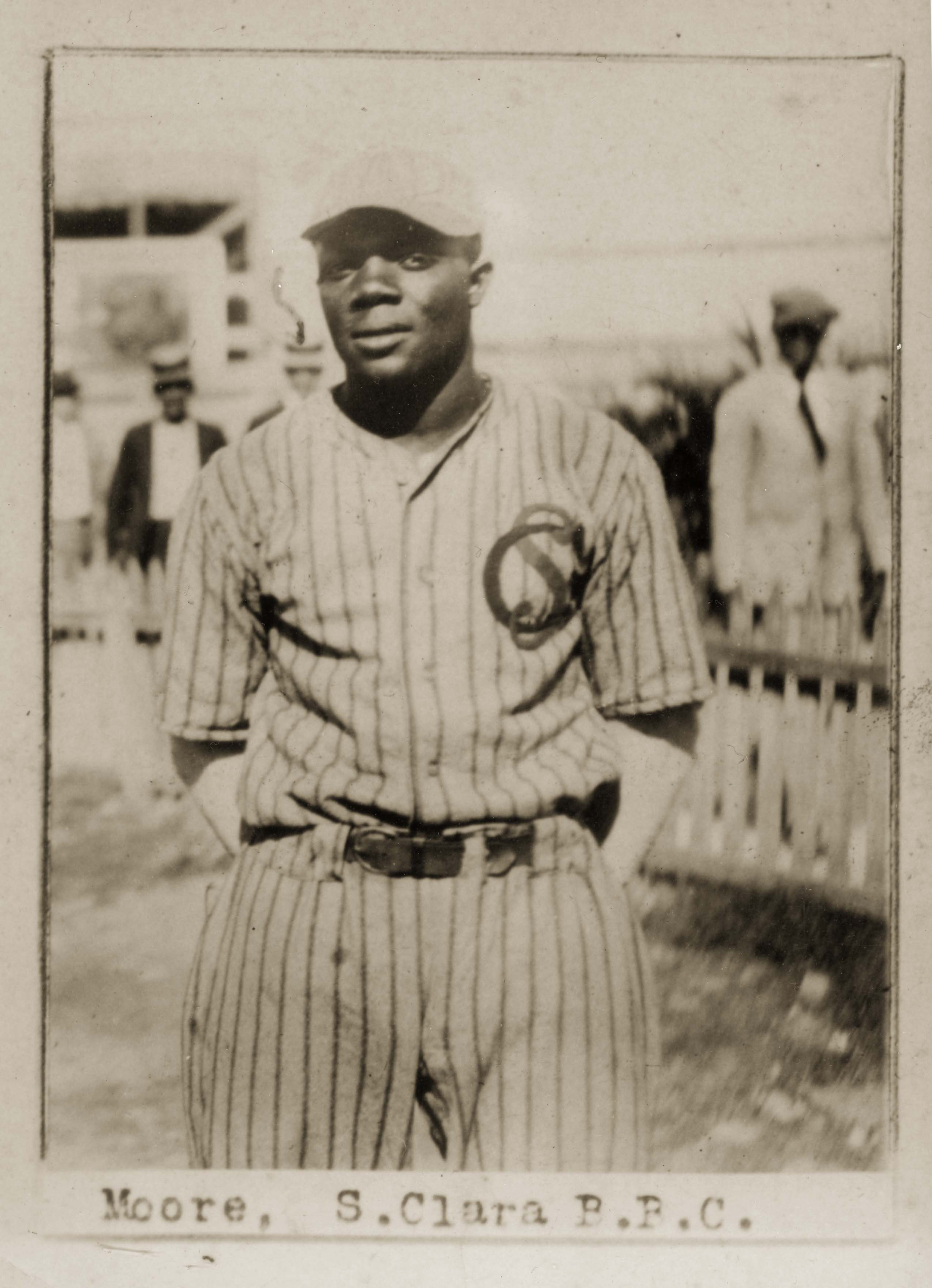

That winter, Moore played in Cuba for the first time with one of the greatest teams ever assembled, the Santa Clara Leopardos. In addition to Moore at shortstop, the team featured Frank Duncan behind the plate, Eddie Douglass and Heavy Johnson at first (Johnson left the team midway through the season), Frank Warfield at second, league batting-title winner Oliver Marcell at third, and an outfield of Oscar Charleston, Alejandro Oms, and Pablo Mesa. The pitching staff included Dave Brown, Rube Curry, Bill Holland, and José Méndez.

Moore led the league in hits and triples while hitting .386 (second behind Marcell). The Leopardos went 36-11-1 and held an 11½-game lead over Habana when the regular season was halted. The last place Marianao club was disbanded, their players added to second- and third-place Habana and Almendares, respectively, and a new competition – the Gran Premio – commenced. This competition was meant to have two halves. Santa Clara won the first half, but before the second half could finish many star players were returning to the United States. The championship was never played.35 Moore hit .299 in the Gran Premio.36

Moore was a tremendous bad-ball hitter – a skill players would acquire after extensive barnstorming tours with local umpires behind the plate looking to move games along. Newt Allen said of these bad pitches, “I’d let them go, but he’d knock them two blocks.” Frank Duncan said, “I’ve seen them throw a curveball to him, break in the ground, bounce up, and he hit it all up-side the fence.” Allen added, “There were no bad pitches for him.”37

The 1924 season was another excellent one for the Monarchs and Moore. He hit .355 while the team won the Negro National League pennant. They faced the Eastern Colored League champions Hilldale of Philadelphia in the first Colored World Series. Moore hit .300 in the series (12-for-40, second only to Rogan’s .350) with seven runs scored and four runs batted in. He turned in a huge performance in Game Six, as Kansas City was down three games to one (Game Two ended in a tie). Moore went 3-for-4 and scored a pair of runs in a tight 6-5 victory. He collected three more hits in Game Eight, another close win, 3-2. Finally, he singled and scored the first of five runs in the eighth inning to break a scoreless deadlock. The Monarchs won the series, five games to four.38

After the season, Moore returned to the California Winter League. He went on perhaps the greatest offensive run of his career, though partially aided by a new, smaller ballpark; Moore led the league in batting (.487), slugging percentage (.873), hits (77), doubles (17), triples (four), and home runs (12). Final RBI numbers were not published, but it is likely that Moore was the league’s Triple Crown winner.39 His batting exploits earned him a fancy new suit for hitting the Diamond Tailoring Company’s advertisement on the outfield wall.40

Moore was one of the greatest players in the history of the California Winter League. He is the all-time leader in batting average (.385) among players with 300 or more at-bats. He was also ninth in doubles (28) and fourth in triples (13). His 13 home runs ranked just outside of the top 10.41

By 1925, Moore was 29 years old. He hit .312, the lowest mark of his career but still enough to be the top-hitting shortstop in the league. The Monarchs faced the St. Louis Stars in a best-of-seven series for the Negro National League pennant. Moore hit only .148 (4-for-27) in the series, but he dominated the first game. He tripled in the opening frame to drive in the Monarchs’ first run. Later, with the game tied at five in the eighth, he belted a two-run home run to help secure an 8-6 win. The Monarchs won the series in seven games.

In a World Series rematch with Hilldale, Moore topped all Monarchs hitters with a .364 average (8-for-22), three doubles, a triple, and four runs batted in. However, the rest of his team floundered, as they failed to drive Moore home even once. Hilldale won the series in five games.

Moore didn’t play any ball that winter, and he seemed refreshed for the 1926 season. He got off to a torrid start, hitting .400 through his first 17 games. On May 18, he went 2-for-742 in a 15-inning Monarchs win on Ladies Day.43 It was the last game he would ever play for the Monarchs. Chet Brewer told Negro League chronicler John Holway about how that evening there was “a big party for all the Monarchs and their wives. Everyone was there but Moore. He was out with that woman.”44

“That woman” was 22-year-old Elsie Brown.45 Exactly what happened that night may never be fully understood; just about the only fact that is universally agreed upon is that Brown shot Dobie Moore in the leg that night, breaking the shortstop’s tibia and fibula into six pieces, effectively ending his baseball career.46

Moore’s initial story was that he went to Brown’s place looking for a friend. He knocked on both the front and back doors before going into the yard to peek through the window. At that point, he said, Brown mistook him for “a prowler” and shot him.47 In another report, Moore said he knocked on the front door, but she responded that she was already in bed. Then as he walked past the house, she mistook him for a prowler and fired.48

Brown initially told reporters a story that confirmed Moore’s. But she later gave a different statement to the prosecutor’s office in which she claimed she and Moore “had a quarrel and that [Moore] had struck her three times in the face, the eye, and the back of the head.” Brown continued to say that she “closed the door in his face and as he went away, he looked up and saw her in a window and threw something at her. [Brown] says she jumped back from the window and came back with a pistol, firing once.” Moore laughed off Brown’s version of the story, suggesting “someone told [Brown] that if she said I hit her she would get off. She does not have to say that. I’ve told the truth and I have no intention of prosecuting her. Why, man, if I had hit her, she would never have been able to lift a pistol.”49

This version of Brown’s story adds a whole new wrinkle to the saga. Instead of it being a chance encounter, it fueled reports that Brown was the girlfriend of Moore, who was married. Rather than visiting Brown’s home, it is also reported that Brown owned a brothel that Moore visited that night. Other reports suggest that it wasn’t the gunshot that ended Moore’s career, but rather the jump from the second-story terrace to evade a follow-up bullet that fractured Moore’s leg.50, 51, 52

Moore underwent surgery June 2 to set the leg and started his recuperation at Wheatley-Provident Hospital.53 Newt Allen told author and historian Phil S. Dixon that soon after the incident Brown relocated to Anthony, Kansas, in view of concerns about her safety.54 Later that year, Moore moved to Detroit, where many of his family members were now located.55 It does not appear his wife, Frances, went with him.

Moore mostly faded from public view, but in 1935 he was announced as a new player for the semipro Detroit Mohawks (though it is unclear if he ever played for them).56 In 1940, Moore was living in Detroit with his sisters Anna (King) and Mildred (with Mildred’s husband, James Tate). Annie passed away in 1944, but Dobie was still living at the same address as of 1947.57 In the meantime, a photo of Moore appeared in the Chicago Defender on September 11, 1943. In the photo he is sitting with crutches by his side, pointing to the spot where he was shot by Elsie Brown.58

On August 20, 1947, Moore died of a heart attack at home in Detroit.59 He was just 51 years old.

There is no shortage of quotes about Moore’s ability. Casey Stengel famously said, “Moore is one of the best shortstops who will ever live.”60 Chet Brewer, who came up with the Monarchs when Moore was in his prime, called him “about the greatest shortstop I ever saw.” Brewer added, “Willie Wells was a great fielder, but he didn’t have the strong arm or the power Moore had. Moore was the best I saw, overall.”61 Babe Herman of the Dodgers faced Moore several times in the California Winter League and called him the best Black player ever.62 J.L. Wilkinson’s son Richard said he was “just as good as Jackie Robinson.”63 Cumberland Posey stated, “Moore is the peer of all shortstops, colored or white.”64

In April 1952, the Pittsburgh Courier published a poll in which 31 Negro League experts (21 former players, and 10 executives and sportswriters) voted for the best Black players of all time. At the shortstop position, John Henry Lloyd was named to the first team with Willie Wells on the second. Dick Lundy and Moore were listed within the article as next on the list (but it is not clear if they were third and fourth or tied for third).65

In 2006, The Committee on African-American Baseball presented a ballot of Negro League candidates for the Hall of Fame following several years of research funded by Major League Baseball. Moore was on both the 94-candidate preliminary list and the final 39-candidate ballot (29 from the Negro Leagues and 10 from the Pre-Negro League era). Moore was not among the 17 of the 39 candidates who were selected for induction. Author Steven R. Greenes suggested that a Moore induction would be a tough sell from a marketing perspective owing to the unseemly nature of his retirement. “How would you like to explain to the press,” a voter asked Greenes, “that Dobie Moore’s career ended with a whorehouse shooting?”66

The statistics that were presented as a part of that Committee (as well as supplemental work done by the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database team) have raised Moore’s profile among new generations of fans. In Bill James’ 2010 book The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, he referred to Moore as the “best unrecognized player” in the Negro Leagues, the best overall player in the Negro Leagues in 1924, and the fourth-best shortstop (after Lloyd, Wells, and Lundy). He also named Moore and Newt Allen as the best double-play combination in Negro League history.67

In 2021, the tireless statistical research of Gary Ashwill, Scott Simkus, Mike Lynch, Kevin Johnson, and Larry Lester of the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database was added to the Baseball Reference website. Dobie Moore, along with all other major Negro League players from 1920-48, finally had his statistics presented alongside American and National League counterparts. The site shows a career batting average of .350 for Moore with an on-base percentage of .393 and a slugging percentage of .524. His statistics per 162 games include 228 hits, 133 runs, 42 doubles, 18 triples, 12 home runs, 138 runs batted in, 24 stolen bases, and – perhaps most impressively – 8.8 wins above replacement (WAR), the best ever for a shortstop and tied with Barry Bonds for seventh among players with more than 400 games played.

The Hall of Fame removed any question of whether Moore is eligible for induction by making him a finalist in 2006. While he played in only seven Negro League seasons, he played another four at a high level for the 25th Infantry, one of the top teams outside the American and National Leagues. Moore generated awe from his contemporaries, even years after his early demise, and modern statistical archeologists have constructed an astounding resume. Dobie Moore is truly one of the overlooked legends in the history of the game.

Acknowledgments and Photo Credit

This story was edited by Rory Costello and Mike Eisenbath and fact-checked by Gary Rosenthal.

Photo: SABR/The Rucker Archive.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and game logs provided by Kevin Johnson of the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database.

Notes

1 Larry Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs, Jefferson: McFarland & Company (2014): 82.

2 1940 United States Federal Census. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/119896?token=3%2BsHvbW6YSM%2FOGt9%2F7UxNpsorq4hrwccTiCxOKOCnKo%3D

3 Gary Ashwill, “Dobie Moore in the Wild West,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2016/06/dobie-moore-in-the-wild-west.html, accessed December 26, 2022.

4 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 82.

5 https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2019/09/dobie-moore-one-last-word.html

6 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers, Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books (1988): 194.

7 “Great Game Won by Twenty-Fifth,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 23, 1916.

8 “Travelers Fail To Travel When 25th Wins Game,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 26, 1916.

9 “Burke’s Men Meet Defeat In Great Contest with Twenty-Fifth Infantry Diamond Stars,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 27, 1916.

10 Adam Darowski, 25th Infantry Wreckers, http://darowski.com/wreckers, accessed October 11, 2022.

11 Darowski, 25th Infantry Wreckers.

12 “All-Star Squad of Oahu-Service League Selected,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 5, 1918.

13 Darowski, 25th Infantry Wreckers.

14 Carlos Francisco Parra, “Battle of Ambos Nogales signaled birth of border fence,” Nogales International, accessed July 21, 2022.

15 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 82.

16 Gary Ashwill, “Dobie Moore: One Last Word,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2019/09/dobie-moore-one-last-word.html, accessed December 21, 2022.

17 Holway, Blackball Stars: 195.

18 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 82.

19 Bill Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch: Dobie Moore, Casey Stengel, and the Lost Box Scores of 1919,” International Pastime, http://billstaples.blogspot.com/2019/12/the-making-of-monarch-dobie-moore-casey.html, accessed July 21, 2022.

20 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch.”

21 “Nogales Doughboys Will Play Three Games with Casey Stengel’s Stars,” Arizona Daily Star, October 31, 1919.

22 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch.”

23 Staples Jr., “The Making of a Monarch.”

24 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Walter-Dobie-Moore.pdf, accessed December 21, 2022.

25 Elizabeth Nix, “Why Were American Soldiers in WWI Called Doughboys?” History.com, https://www.history.com/news/why-were-americans-who-served-in-world-war-i-called-doughboys, accessed December 27, 2022.

26 Dobie Moore Game Logs provided by the Seamheads Negro League Database, September 7, 2022.

27 Phil S. Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs, Jefferson: North Carolina McFarland & Company (2010): 34.

28 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 83.

29 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Walter-Dobie-Moore.pdf, accessed December 21, 2022.

30 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore.”

31 Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs: 46.

32 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore.”

33 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore.”

34 Frances Davis in the Missouri, U.S., Marriage Records, 1805-2002. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/830985?mark=e2383ff24fb6eb4a5c669190bce337d5436545224c2d1854299a4939fd8db825

35 David C. Skinner, “Twice Champions: The 1923-24 Santa Clara Leopardos,” SABR, https://sabr.org/journal/article/twice-champions-the-1923-24-santa-clara-leopardos/, accessed December 21, 2022.

36 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore.”

37 Holway, Blackball Stars: 191-192.

38 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 104-181.

39 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Walter “Dobie” Moore.”

40 “Moore Has a New Suit,” California Eagle, January 16, 1925.

41 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (2002): 245.

42 Dobie Moore Game Logs provided by the Seamheads Negro League Database, September 7, 2022.

43 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (2016): 58.

44 Holway, Blackball Stars: 197.

45 “Negro Shortstop is Shot,” Kansas City Times, May 19, 1926.

46 “Shortstop Will Not Prosecute Woman, He Says,” Kansas City Call, May 21, 1926.

47 “Negro Shortstop is Shot.”

48 “Shortstop Will Not Prosecute Woman, He Says.”

49 “Shortstop Will Not Prosecute Woman, He Says.”

50 http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Walter-Dobie-Moore.pdf

51 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers (1994): 566.

52 Gary Cieradkowski, The League of Outsider Baseball: An Illustrated History of Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes, New York: Touchstone (2015): 163.

53 “Monarchs Home Saturday,” Kansas City Call, June 4, 1926.

54 Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs: 62.

55 Gary Ashwill, “Dobie Moore Update,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2013/05/dobie-moore-update.html, accessed December 26, 2022.

56 “Former Stars of K.C. Monarchs Join Mohawks Club,” The Tribune Independent of Michigan, December 15, 1934.

57 U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 for Allen Melton Moore. Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/sharing/884810?mark=24945941e6de9f2977d816bcf92abb62e83e49813b7ac0a9113d72ff5aae6c61.

58 Gary Ashwill, “Dobie Moore,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2007/10/dobie-moore.html, accessed December 26, 2022.

59 Gary Ashwill, “The Latest on Dobie Moore,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2014/05/the-latest-on-dobie-moore.html, accessed December 26, 2022.

60 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 83.

61 Holway, Blackball Stars: 192.

62 Chris Jenson, Baseball State by State: Major and Negro League Players, Ballparks, Museums and Historical Sites, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (2012): 71.

63 Holway, Blackball Stars: 191.

64 Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: 83.

65 “Power, Speed, Skill Make All-America Team Excel,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1952.

66 Stephen R. Greenes, Negro Leaguers and the Hall of Fame, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, (2020): 218.

67 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, United Kingdom: Free Press (2010): 180, 186.

Full Name

Walter Moore

Born

February 8, 1896 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

Died

August 20, 1947 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.