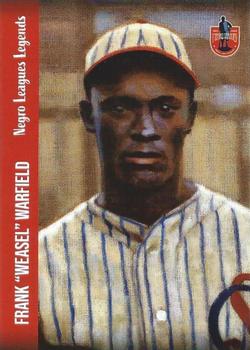

Frank Warfield

Frank Warfield may be one of the least understood and appreciated stars of the Negro Leagues, and possibly one of the most unjustly maligned. He stood just 5-feet-7-inches tall and was slight in stature, but he was feisty, fast, and, some would say, furious. Yet few player-managers in the Negro Leagues achieved as much as did Frank Warfield.

Frank Warfield may be one of the least understood and appreciated stars of the Negro Leagues, and possibly one of the most unjustly maligned. He stood just 5-feet-7-inches tall and was slight in stature, but he was feisty, fast, and, some would say, furious. Yet few player-managers in the Negro Leagues achieved as much as did Frank Warfield.

Frank Warfield was born on April 28, 1899, in the small farming community of Pembroke, in Christian County, Kentucky. He was the only child born to Richard and Lela Rollins Warfield. His mother died when Frank was less than 3 years old. The year of Warfield’s birth is up for debate. Kentucky did not routinely issue birth certificates until 1911, but the 1900 Census indicates that Frank Warfield was born in April 1899. In subsequent years, however, documents, including his World War I draft card, incorrectly state that he was born in 1898. His father, Richard Warfield, was born in Christian County in 1876. He was the son of Walter Warfield, who earned his freedom from enslavement by serving in the US Colored Troops Heavy Artillery during the Civil War. Richard Warfield, who worked as a farm laborer in Christian County, married Lela Rollins on September 30, 1899, approximately five months after Frank’s birth. When Warfield was born, Pembroke was home to fewer than 700 people.1 The town was a stop on the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and was known for growing two things – strawberries and tobacco, both labor-intensive crops.

Frank Warfield’s journey northward to Indiana followed a path taken by many African American Kentuckians during the first wave of the “Great Migration.” From the 1910s to 1940, the majority of African Americans who relocated from the South to cities in Indiana were from Kentucky.2 Warfield’s father was likely aware of the opportunities in cities like Indianapolis from others who already relocated there and from other sources of information such as newspapers. As early as 1889, Christian County residents were subscribing to the Freeman, an African American newspaper published in Indianapolis since 1884.3 For Richard Warfield, the decision to leave Pembroke followed shortly after the death of his wife, Lela, around 1901. Another motivation to leave Pembroke was to escape the racial injustice and violence that was prevalent in Christian County and western Kentucky.4 In the early 1900s, lynchings of African Americans in Christian County and neighboring Todd County were not uncommon.5 Richard Warfield, with his young son in tow, headed first to Louisville, where he worked cleaning railroad cars. After a brief stay in Evansville, Indiana, they moved northward to Indianapolis where they lived off and on for nearly two decades. The Warfields’ move to Indianapolis did not, however, insulate them from racism. By the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was deeply imbedded in Indiana and counted among its allies the mayor of Indianapolis and other influential politicians, including Governor Edward L. Jackson.6

When Richard and Frank Warfield arrived in Indianapolis in 1910, the city of over 233,000 had a large, thriving African American community with many successful Black-owned businesses, including two newspapers with national circulation. Richard Warfield found work as a general laborer. He and his son moved several times within the west side of Indianapolis between 1910 and 1920, with their longest tenure at 408 Smith Street, which was also Frank’s last known address in Indianapolis. None of the houses in which Warfield and his father lived are still standing. All were demolished, along with at least 8,000 other structures, to make way for urban-renewal projects and the development of the “Inner Loop” of Interstates 65 and 70.7

Frank Warfield’s name first appeared in an Indianapolis newspaper not for playing baseball, but rather for gunplay. When he was 11 years old, Warfield was shot in the shoulder by a friend while the boys were playing with a pistol.8 It was reported that the bullet either grazed Warfield’s shoulder or passed through it, and that the 17-year-old boy who pulled the trigger was so mortified by the experience that “his friends believe he may be dead of heart disease due to the fright over the accident.”9 The description of the superficial gunshot wound was likely correct given that Warfield’s World War I draft card listed no visible physical disqualifications, nor did it impact his ability to play baseball.

Nearly three years to the day after the shooting, Warfield’s name made the newspaper again, but this time it was for his debut as a baseball player. On June 21, 1913, Warfield appeared in the lineup as the right fielder for the Denison Cubs, a peripatetic team composed mainly of amateur players, many of whom were employees of the Denison Hotel of downtown Indianapolis.10 Warfield and his team acquitted themselves admirably and were described as doing “as good work as members of the A. B. C.’s. [sic]”11 Warfield spent the summer of 1913 with the Denison Cubs, earning valuable experience against local nines – both White and Black teams. At the age of 14, he was already demonstrating his gifts for stealthy and savvy baserunning.”12 Later in his career, these talents earned him the nickname Weasel Warfield.

Two major events marked Frank Warfield’s life in 1914. In March his father, Richard Warfield, widowed for more than a decade, married Lizzie Littlejohn in Indianapolis. It was likely the first time in Frank Warfield’s memory that a woman lived in his household. Sharing a home with newlyweds may have been an incentive for Warfield to get out of the house and play baseball, which precipitated his second watershed moment in 1914: playing in his first true semipro and professional baseball games. At the beginning of the 1914 season, Warfield joined the Eastern Black Sox, a semipro traveling team composed largely of former and future players for the Indianapolis ABCs. The Eastern Black Sox fielded teams in 1913 and 1914, before folding in the summer of 1915. The addition of Warfield contributed to the team’s prospects, and they had nowhere to go but up; in 1913, they had lost a game to the ABCs by the score of 38-9.13

When Warfield hit the road with the Eastern Black Sox during the summer of 1914, they were promoted as “baseball vaudeville” and “baseball jugglers,” but also as the “fastest colored baseball team in three states.”14 Warfield spent most of his time tending to the gardens in left field. Soon, at age 15, Warfield experienced his first taste of organized baseball when he suited up as the starting shortstop for the Indianapolis ABCs for a June 28 game against the Louisville White Sox at Spring Bank Park in Louisville.15 The ABCs defeated Louisville, 11-10, and, despite committing two errors, Warfield copped a walk, swatted a double, and scored on a fly ball.16 And, even though the ABCs’ manager, C.I. Taylor, sent “some subs” to Louisville and saved most of his “regulars” for a home tilt against the Cuban Stars, Warfield’s brilliance outshone his bungles, and he caught the attention of one reporter who noted that “Young Warfield is a very fast man on bases and very promising.”17

Warfield started 1915 where he had left off the year before – playing left field for the Eastern Black Sox and making brief appearances with the Indianapolis ABCs. The 1915 Black Sox lineup was bolstered by former ABCs players George Beard, Bernie Lyons, Otis “Cat” Francis, and Jack “The Poor Fighting Boy” Hannibal. Despite the infusion of veteran talent and a new team manager, the Eastern Black Sox folded in midseason.18 Less than two weeks after the demise of the Sox, Warfield was picked up by the Indianapolis ABCs to patrol left field for a doubleheader against the Louisville White Sox, but this time it was a homestand and Warfield was on the varsity squad. He was enlisted to fill in a vacancy in the outfield created when Oscar Charleston was “out of the line-up, owing to a bit of misunderstanding with the management.”19 Warfield was planted in left field, while George Shively migrated to center to cover Charleston’s usual domain. Indianapolis split the twin bill with Louisville, winning the first game, 5-0, but losing the nightcap, 8-4.20Warfield went hitless in four plate appearances in the opener, but showed some promise in the second with two singles and a stolen base, although he also committed an error.21 The next day, the ABCs downed the Louisville White Sox, 9-0, with Warfield once again blanked at the plate.22 Warfield’s duties with the ABCs in 1915 were short-lived and unremarkable, lasting just three games, and ending with Charleston’s return to good graces. Afterward Warfield found a new baseball home with the French Lick Plutos, a traveling semipro team based in French Lick, Indiana, with a lineup that was nearly identical to that of the defunct Eastern Black Sox.

In 1916 Warfield started out with the newly formed Bowser’s Indianapolis ABCs, and finished the season with the St. Louis Giants. In early 1916 Tom Bowser and C.I. Taylor dissolved their partnership in the Indianapolis ABCs, and each formed new teams using their names and the ABC moniker.23 Warfield, along with former ABC players Oscar Charleston and Bingo DeMoss, chose Bowser’s aggregation over Taylor’s squad.24 With DeMoss presiding over second base, Warfield was relegated to patrolling right field. By mid-June, however, Warfield jumped to greener pastures by signing with the St. Louis Giants of the Western Independent Clubs, of which Taylor’s ABCs were members. He was just 17 years old and the only teenager on the Giants’ roster. He played in 27 games for St. Louis and posted some flashy numbers for such a young player. Warfield batted .343 and was tied with Jimmie Lyons for the most stolen bases on the team with 17. The St. Louis Giants, however, underperformed in 1916, finishing the season as an also-ran in the Western Independent Clubs standings, winning less than half as many games as the top club, the Chicago American Giants.

During the 1917 and 1918 seasons, Warfield remained with one team – C.I. Taylor’s Indianapolis ABCs. In the spring of 1917, he “excited the hometown fans” with his defensive flair as an infielder.25 But for the bulk of the year, Warfield was relegated to residing in right field, where he made some dazzling catches.26 As the season wore on, he saw more frequent infield assignments, mainly at second base. Toward the end of 1917, Warfield saw more action at short, especially when the ABCs’ regular shortstop, Morten “Specs” Clark, was no longer effective because, according to one sportswriter, Clark’s “eyes have gone.”27 Warfield’s gifts with the glove offset his mediocre output at the plate as he finished the year with an anemic .214 batting average. The ABCs capped off the regular season by proclaiming themselves as “world’s series” champions over the Chicago American Giants, an opinion not shared by Rube Foster, who vehemently disputed the outcome of the series.28

Warfield’s 1918 season with the ABCs saw him emerge as a full-time infielder. He started the season at shortstop but was also platooned at second with C.I. Taylor’s younger brother James “Candy Jim” Taylor. The season was a challenging one for Warfield and the ABCs. As they battled to retain their disputed championship title, they also faced two more formidable foes; human and material resources lost to World War I and the influenza pandemic of 1918. All the clubs in the league played fewer than 50 games, and as the draft took more players to Europe, the number of available opponents dwindled.29 That summer, the ABCs often found themselves playing mostly local nines and squads composed of military personnel. In one such game, played on the Fourth of July, the ABCs downed the “Aviation” nine, who were in training at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, with Warfield providing some fireworks of his own by rocketing a home run over the left-field fence.30

Despite the ABCs’ lineup that included two future Hall of Famers, C.I. Taylor’s other brother, Ben Taylor, and Oscar Charleston, they finished the abbreviated season in second place in the Western Independent Clubs race, losing the title to their nemesis, the Chicago American Giants. Warfield’s batting average improved dramatically to .330 in 1918, although he appeared in 28 fewer games than in the previous year. The 1918 season sputtered to an end by early October when the influenza pandemic resulted in the prohibition of public gatherings, including baseball games. What likely would have been the final game of the season, a tilt against the Muncie Greys, the “white champions of Indiana,” was nixed by order of the Muncie health board.31 There was speculation in the press that Warfield would be drafted into the military, but that was not the case.32 Frank and his father, Richard Warfield, both registered for the draft on September 12, 1918, but neither was inducted into the military. Frank Warfield did his patriotic duties at the close of World War I as a shipping clerk for the Indianapolis Red Cross, boxing up relief supplies and some of the 20,000 Christmas packages sent to doughboys serving in France.33

Frank Warfield’s 1919 season could be best described as “the same but different.” It was the same in that he began the year working as a clerk in C.I. Taylor’s billiard parlor and cigar store in Indianapolis, a job he had held in previous years. It was different because he did not play baseball for Taylor’s ABCs. In fact, 1918 was the last year that Warfield wore the ABCs’ uniform. The reason for this was that Taylor did not field an ABC team in 1919, citing postwar difficulties in securing a worthy roster and shifting his focus toward his other business enterprises.34

When Warfield left the employment of C.I. Taylor, he also lost a connection to his mentor and tough taskmaster, and, in a sense, his baseball father figure. Unemployed and undeterred, Warfield packed his bags and baseball acumen, and signed as the starting second baseman with Tenny Blount’s newly minted Detroit Stars. Another difference for Warfield in 1919 was that for the first time in his career as a full-time professional baseball player, he did not start the season as a teenager. On April 28, 1919, Warfield turned 20 years old. He played in all but two of Detroit’s 41 games. Although his batting average was a meager .215, he made the most of his plate appearances by garnering 22 walks, led the team in triples, and then used his aggressive and savvy baserunning to cross the plate 35 times. Another dissimilarity between 1918 and 1919 for Warfield was that he played for two teams, the Detroit Stars and the Dayton Marcos. In the postseason, Warfield had one start for the Marcos at short, in a losing effort against the Chicago American Giants.35 And in an odd twist of coincidence, the “same but different” situation occurred in 1920 – Warfield played 99 percent of the regular season with one team and was added to another team’s roster in the postseason. The difference was that in 1919, Warfield had played for the lowly Marcos who never had a winning season as members of the Western Independent Clubs or the Negro National League, whereas in 1920 he joined the Chicago American Giants just in time for their championship run.

Warfield donned his Stars uniform once more in 1920 and took up residence at second base. He resumed his slot as the leadoff man for Detroit and drew the attention of the baseball press and public for his offensive and defensive talents. Warfield started the season off on the right foot in April with “an exhibition of base running never witnessed in Mack Park,” and by midsummer was described as “among the best keystone sackers in colored circles.”36

By the end of the regular season, Warfield had compiled a respectable .281 batting average for the Stars and was second only to former St. Louis Giants teammate Jimmy Lyons in hits and runs scored. The Stars finished the season in second place the National Negro League standings, bested by the Chicago American Giants for the honor of hoisting the pennant.

For Warfield, though, his season was extended after he was picked up by Rube Foster to play in a Negro League “world series” against the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants of the Eastern Independent Clubs. Foster needed an able infielder to step in and fill the vacancy created at shortstop when Chicago’s Bobby Williams jumped to the Dayton Macros in mid-September.37 Warfield appeared in four games for Chicago. He had just two hits during the series, but his fly ball in the second game of a doubleheader on October 17, 1920, resulted in the only run scored and a victory for the Chicago American Giants.38

Warfield remained with Rube Foster’s American Giants when they took up winter residence in Palm Beach, Florida, as the Royal Poinciana Hotel nine, and played against John Henry “Pop” Lloyd’s team that represented the Breakers resort hotel.39 Warfield was demoted to outfield duties when Bobby Williams returned to the American Giants’ lineup in the postseason and reclaimed his residence at second base.40 On their postseason swing through Southern states, Warfield and the Chicago American Giants crossed bats with local teams in Atlanta and Memphis.41 Warfield’s “spirited winter’s play” for Foster’s American Giants was duly noted and he was “universally regarded as being without a peer as a second sacker.”42

Between 1919 and 1922, Warfield made a habit of playing for the Detroit Stars during the regular season and picking up a postseason gig with a different team. This appeared to be a good strategy. He was credited in 1920 for having “aided materially in the big things that the Foster club put over in the East,” and, in the 1921 postseason was “holding down the hot corner in the K.C. Monarchs’ line up in the post-season scrap.” In 1921 the Detroit Stars finished another also-ran season while Warfield continued to hone his skills. The Chicago Whip was particularly enamored with Warfield as he “led the attack for the Detroiters this season,” adding that as “one of the leading second-sackers in the game, the midget Star has played all positions this season.”43 As the leadoff man for Detroit, he ended the season as the team’s top run producer and maintained a .264 batting average. In the 1921 postseason, Warfield was picked up by the Kansas City Monarchs.44

In the spring of 1922, Warfield returned for his final season with the Detroit Stars, and he made the most of it. His batting average soared to .318 and led his team in runs scored with 70 trips across the platter. Warfield was described as a “Keystone artist” and on par with the league’s other outstanding second baseman, Bingo DeMoss of the Chicago American Giants.45 But the Stars’ new player-manager, Bruce Petway, could not lift the men out of the doldrums and once again Detroit was an also-ran in the Negro National League. As he had done in the three previous years, Warfield picked up a postseason gig, this time as a second baseman with the St. Louis Stars. Warfield was in the lineup for St. Louis when the Stars bested the barnstorming Detroit Tigers in two out of three exhibition games in the Gateway City.46Warfield’s brilliant baserunning provided the winning run in one of the games when he stole home during a daring double steal.47 The outcome of the contests between the Stars and the Tigers was highlighted more than a decade later as the first in a series of articles that appeared in the Chicago Defender to “show that owners and not the players are the ones keeping the color bar in baseball.”48 After Warfield’s season ended in the States, he was enlisted by Tinti Molina’s Santa Clara Club to Cuba for winter league play in early 1922. One of his teammates was third baseman Oliver Marcell, with whom five years later he had a notorious and violent altercation that resulted in damaging consequences to the legacies of both players.

The 1923 season signaled major shifts in Warfield’s baseball life. His early mentor, C.I. Taylor, had died the previous year, and for the first time in his career, Warfield played for a team that was based neither in Indiana nor in a state that bordered it. It was also the first time that he assumed the role of player-manager, a duty that brought him both accolades and derision. From 1923 to 1928, Warfield was a member of Ed Bolden’s Hilldale Club of Darby, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. Joining him in Darby was former Detroit Stars teammate Clint Thomas. Detroit Stars owner Blount lamented the loss of Warfield, and later blamed him for the “Detroit wreckage” of a season.49 Blount said, “I made every effort to have him remain with us,” but he “packed up suddenly and left us.”50 Another addition to Bolden’s team was shortstop Pop Lloyd, who assumed the role of player-manager for Hilldale in 1923.51 Bolden’s calculations paid off in the end with Hilldale winning the Eastern Colored League championship. But there was dissension in the ranks. In late September Lloyd was suspended as manager by Bolden and Warfield was named Hilldale’s new captain.52

Warfield’s new role as player-manager did not sit well with influential sportswriter (later league secretary) W. Rollo Wilson, whose unabashed adoration for Lloyd shaped his reporting on Warfield. Wilson did not hold back in his criticisms of the Hilldale club’s management over Lloyd’s dismissal and insinuated that Warfield was the instigator of Lloyd’s exit. Wilson ranted that “one of the new stars on the team has managerial designs and that he became a little messenger, sub rosa, from the club house to the office.”53 He further alleged that since Lloyd’s departure, “morale of the team has suffered,” and that Hilldale lost most of its most recent games with Warfield at the helm.54 He also questioned how the “older and more experienced men would react to such a change” given Lloyd’s successes and that he “kept the temperamental stars in line.”55 Wilson demanded to know how there could be so much “ill-feeling on a team which won over seven-tenths of the games played” and claimed that the public was similarly outraged.56

In the end, Hilldale did not, as Wilson predicted, fall apart when Lloyd was removed as manager. The reality of the situation was that Lloyd was not as popular in the clubhouse as Wilson believed and was not missed by his players. According to historian Neil Lanctot, Lloyd “seldom endeared himself to the management,” and his “handling of the team quickly alienated several players.”57 Wilson’s dire predictions that Hilldale would collapse under Warfield’s leadership did not come to fruition.58 In fact, Warfield led Hilldale to pennants in the ECL again in 1924, 1925, and 1926. Meanwhile, Lloyd, who, after being fired by Hilldale was named manager of the Atlantic City Bacharachs, failed to win another pennant. It was not until 1930 that Lloyd bested one of Warfield’s teams, when Lloyd’s New York Lincoln Giants finished second and Warfield’s Baltimore Black Sox were third, to the 1930 champion Homestead Grays.

After Lloyd’s ignoble exit from Darby, Wilson continued to use his newspaper column to flog Warfield. He went so far as to try to gin up some dissension of his own during the winter season with a column in the Courier about how Lloyd and his teammates were being paid more money than Warfield and his Santa Clara mates.”59 Wilson failed to acknowledge that Warfield had a much more successful season that winter in Cuba than did Lloyd. Warfield bested Lloyd in nearly every category, including stolen bases, and Warfield’s Santa Clara Club was the 1923-24 league champion. Wilson eventually gave Warfield his due as one of the best second basemen and managers of his era. Nevertheless, in 1958, when Wilson named 11 players that he believed should be in the Hall of Fame, he included John Henry Lloyd and Oliver Marcell, but not Frank Warfield.60

In the spring of 1924, and for the first time in his career, Warfield began the season as a player-manager. But before he took the reins as the captain of the Hilldale Club, Warfield’s .301 batting average helped the Santa Clara club, considered to be the one of the best teams in Cuban League history, win the winter season championship with a 36-11-1 record.61Warfield’s first full season as the player-manager of Hilldale was a spectacular success. Hilldale was the champion of the ECL. Lloyd, whose leadership skills were hailed as nonpareil by W. Rollo Wilson in 1923, finished three places behind Warfield in the league standings. Despite losing the “East-West world series” to the Kansas City Monarchs in “ten of the most hotly contested games in diamond history, the 1924 season was a notable one for Warfield.”62 He posted a .309 batting average during the regular season, the best of his career as a player-manager, stole 22 bases, and banged out 14 doubles, another career high.

Warfield headed to Cuba for the winter of 1924-1925, just as he had done in the previous few years. But one statistic attributed to Warfield’s postseason engagements that was overlooked was his acquisition of a spouse. Although a marriage license has yet to surface, immigration documents from the winters of 1924 and 1925, indicate that a “Mrs. Frank Warfield” was born in Springfield, Ohio, in May 1898. In both years, the ships’ manifests identified Frank Warfield as “married.” On March 17, 1924, Frank Warfield of Philadelphia and “Mrs. Frank Warfield” of Detroit arrived in Key West, Florida, from Havana, along with several other ballplayers. On February 20, 1925, when Warfield sailed from Havana to Key West, he was accompanied by “Eva Warfield,” of Philadelphia. Eva Warfield’s identity is as mysterious as her entrance and exit from Frank Warfield’s life. Prior to 1924, and after 1925, she disappears from the public record, and there is no evidence to suggest that the couple had any children. Warfield’s marital status on his death certificate states that he was “single” rather than married, widowed, or divorced.

Thanks to W. Rollo Wilson, another puzzling aspect of Warfield’s identity surfaced in early 1925. In his column for the Courier, Wilson wrote about “Francis Xavier Warfield” and the demise of the Santa Clara club.63 Wilson continued to use this nomenclature for Warfield into 1926.64 It is unclear why Wilson baptized Warfield with such a Catholic-sounding name. Warfield never signed a document with a middle name, let alone with “Xavier.” No evidence has surfaced to indicate that Warfield was Roman Catholic. No known parish records mention Warfield’s name and he was not buried in a consecrated Catholic cemetery. In all likelihood, Wilson was influenced by the name of a popular contemporaneous White baseball player, Francis Joseph “Lefty” O’Doul, who was renamed “Francis Xavier O’Doul” by at least one sportswriter.65 O’Doul’s contributions to the development of baseball in Japan earned him a spot on the 2021 Hall of Fame’s Early Baseball Era Committee’s ballot, though he fell short of enshrinement.

In 1925, at the age of 26, Frank Warfield became the youngest player-manager to win a World Series when Hilldale avenged its 1924 loss to Kansas City by dethroning the Monarchs in five of six games. No other Negro League player-manager ever accomplished this feat. The youngest White player-manager to win a World Series was Hall of Famer Bucky Harris, who at age 27, led his Washington Senators to victory over the New York Giants in 1924. Young Warfield’s success as a manager was noteworthy, especially since the 1925 Hilldale squad was devoid of “squabbling” and “petty grievances,” and was adjudged to be the best in the team’s history.66 It is noteworthy that such harmony existed in the Hilldale clubhouse during such a turbulent season. This is especially true for a year overshadowed by poor umpiring and precarious finances.67 Even the World Series victory was bittersweet given that fewer than 1,500 fans witnessed the final tilt and the payout was meager. As John Holway noted, “Many players felt that they could have made more barnstorming against whites.”68

The 1926 season was Warfield’s last full season as Hilldale’s player-manager. Although he scored the most runs on the team that season, his offensive output began a steady decline. It is ironic that after Warfield’s career peaked in 1925, W. Rollo Wilson reversed course and began to heap praise on Warfield. Wilson’s retort to fans’ cries of “wahassamatter [sic] with Warfield?” was, “The Clan Darbie [sic] captain and field manager is perhaps the best second baseman in Negro baseball these days,” and, in a complete about-face, asserted that since he replaced John Henry Lloyd in 1923, Warfield “has proved his worth ever since.”69 Despite Wilson’s boosterism, Warfield’s 1926 season ended with a thud. Hilldale lost the 1926 ECL title to the Atlantic City Bacharachs, and his team and league faced financial and franchise failures.70Warfield’s gloom deepened in November when his stepmother, Lizzie Littlejohn Warfield, died in Indianapolis from tuberculosis at age 43.

Warfield’s final season with Hilldale, 1927, coincided with the team’s slide into irrelevance in the ECL. By midsummer he was demoted from player-manager to just player, and he was replaced as the Hilldale leader by Otto Briggs. One pundit remarked that “it was thought wise to have [Warfield] relinquish the responsibility … as it seems to have affected his playing since Hilldale began going bad this season.”71 Warfield muddled through the remainder of 1927, playing 55 games at second for Hilldale and batting just .219. His defensive skills, however, remained strong. Even longtime critic W. Rollo Wilson acknowledged this when he named Warfield to his “all-Eastern League club.”72 Warfield jumped to the Baltimore Black Sox at the close of the season, playing a handful of games for a familiar face – Black Sox manager Ben Taylor.

The Charm City worked its magic on Warfield in 1929 when he was named player-manager of the Baltimore Black Sox. It was his best team since the 1925 Hilldale club. Warfield led the Black Sox to the championship of the American Negro League, which had been formed from the ashes of the ECL. Sportswriter Wilson initially questioned the wisdom of Black Sox team owner George Rossiter’s decision to hire Warfield as manager and believed that Baltimore’s Achilles’ heels would be aching at right field and first base, but those predictions proved to be unfounded.73 Jesse James “Mountain”Hubbard flourished in right field. First base was ceded to Hall of Famer Jud Wilson. Warfield had a “million-dollar infield” with Wilson, Dick Lundy, and the mercurial Oliver Marcell, who was acquired from the Bacharachs.74 After the regular season ended, Wilson conceded that the “Black Sox deserved to win the pennant” and that Baltimore “had the best club in the league and a highly efficient leader in Frank Warfield.”75 Wilson also acknowledged Warfield’s ability to maintain clubhouse cohesion and to control “a half dozen temperamental stars, described as “so many barrels of gunpowder,” and thought that “Warfield trod lightly and blithely over them with never an explosion or consequence.”76Wilson’s description of Warfield’s ability to keep the peace is important to note since some authors who have written about Warfield decades after his death often have described him as having a reputation for being divisive, hot-tempered, and combative.

During the 1929 season, Warfield faced one of his biggest challenges – managing the talented but temperamental third baseman Oliver “Ghost” Marcell, who was among the players that W. Rollo Wilson described as “barrels of gunpowder.”77 Warfield spent the winter of 1929-1930 in Cuba, as did Marcell. Unfortunately for both men, just before leaving Cuba to return to the United States, long-simmering tensions between player and manager exploded in a dispute over an alleged debt. The exact events that transpired in early February in Santa Clara are clouded by a lack of reliable published accounts and distortions that foster greater sympathy toward Marcell while placing more of the blame on Warfield. The brawl, which erupted during a card game in a Santa Clara hotel, resulted from Marcell’s lingering anger from the 1929 season when Warfield took Marcell out of the Black Sox lineup due to Marcell being “not in condition or up to form.”78Marcell alleged that Warfield owed him money, and demanded that Warfield make good on the debt so Marcell could cover his heavy losses at the poker table.79 The story goes that “Marcell is said to have made a lunge at Warfield, and in the ensuing scuffle, Marcelle’s nose was badly bitten.”80 As a result of the melee, Warfield spent the night in jail and Marcell spent the night in the hospital.81 Warfield was soon released from custody with no consequences and returned to the United States via Key West on February 3, 1930. Marcell left Cuba four days later.

The outcomes of these unfortunate events had both short and long-lasting impacts on the legacies of both men. The most immediate effect of the fight was that Marcell was traded from Baltimore to the bumbling Brooklyn Royal Giants for what was to become his final season in the Negro Leagues. Despite reports that Marcell had a hair-trigger temper and that he threw the first punch, and that Warfield – the smaller of the two – was only defending himself, Warfield is often portrayed as the bad guy in the fight. In fairness, it is easy to paint Marcell as the more sympathetic character. After all, he lost the end of his nose and resorted to wearing a patch over the nose to hide the disfigurement.82 In subsequent years, the blame for Marcell’s departure from the Negro Leagues in 1930 is often laid squarely on Warfield and the nose-biting incident.83 In truth, Marcell was already at the end of his career. As Bill Gibson of the Baltimore Afro-American put it less than three months after the incident in Cuba, “Since the number of fans are wondering why Ollie Marcelle is not at the hot corner for the Black Sox this season, and probably blaming it upon a little altercation between Marcelle and Warfield in Cuba, last winter, it might be in order to say that had the matter never occurred, Marcelle would have been given the air just the same. … Marcelle’s legs have gone back considerably in the past two seasons.”84

In the end, the Black Sox finished 1930 in third place behind the Eastern Independent Clubs champion Homestead Grays. Warfield continued his downhill slide in 1930, batting a meek .218, and, for the first time since 1914, stealing no bases. One bright note for Warfield’s squad that year was the addition of a new pitching phenom named “Kid Satchells” [sic] – Satchel Paige, who debuted with the Black Sox in May 1930, but drifted in and out of the lineup for much of the season.85

Warfield’s final full season with the Baltimore Black Sox in 1931 had some similarities to the pervious one – except that everyone kept their noses. The Black Sox finished sixth in the nine-team Independent League that saw Warfield’s former team, the Hilldale club, managed in 1931 by Hall of Famer Judy Johnson, win the pennant. For the first time in years, Warfield was not in command of second base, played in only 43 of Baltimore’s 60 games, and barely had a pulse at the plate, posting the lowest batting after of his career (.149). And, for the first time since 1915, he produced no extra-base hits. His precipitous decline could be attributed to the stress of managing his players and some of the Black Sox’ business dealings. It is more likely, however, that the 32-year-old Warfield was already suffering from the effects of tuberculosis, the disease that took his life the following year.

In March 1932 it was announced that Warfield would take the helm as player-manager of the newly formed Washington Pilots of the East-West League.86 The Pilots were a far cry from the Hilldale and Black Sox teams that took Warfield to the top of the game. The team lost a string of games in the spring thanks to an error-prone infield and wildly inconsistent pitching. In their opening home game, at Griffith Stadium, the Pilots committed a half-dozen errors, two by Warfield, in an 8-2 loss to Hilldale.87 The East-West League was in no better shape than the errant Pilots, and by the end of June questions arose as to whether or not the entire operation would fall apart before the close of the season.88 It was reported that teams were struggling to make payrolls and at least one league official “had ceased sending in box scores … because he found it a waste of time and effort.”89

Undeterred, Warfield shored up the Pilots’ infield with the additions of Hall of Fame first baseman George “Mule”Suttles, third baseman Dewey Creacy, and shortstop Jake Dunn.90 Warfield himself was appearing less frequently in the lineup and ceded dibs on second base to Sammy Hughes. In July Warfield made plans for a series of road games with the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords.91 On July 4, 1932, Warfield made what was probably his last plate appearance when he pinch-hit for pitcher Ted Trent in the first game of a doubleheader against the Grays. Warfield went out with a bang. When he came to the plate in the bottom of the ninth, he hit a grounder that was bungled by Grays third baseman Walter Cannady, allowing two runs to score and seal the 4-2 walk-off victory for the Pilots.92

On Friday, July 22, 1932, the Pilots opened a weekend series against the Pittsburgh Crawfords at Greenlee Field, but Warfield did not put himself in the lineup. The Pilots were sunk by the Crawfords, 4-3.93 On Sunday, July 24, in the last game of Warfield’s career and the last day of his life, the Crawfords destroyed the Pilots, 14-5.94 After the game, Warfield and Pilots business manager Douglas Smith were headed back to the Bailey Hotel, located in the Hill District, Pittsburgh’s historic African American neighborhood, about a block from Gus Greenlee’s Crawford Grill. Along the way, Warfield was suddenly stricken and by the time they arrived at the hotel, he was dead.95 The time of death was estimated at 6:55 P.M., not long after the end of the Pilots game. Smith signed the death certificate as the “informant.” Smith identified himself as Warfield’s “friend,” but was not so close a friend to know Warfield’s correct birth and family information.

There has been much speculation about the circumstances of Warfield’s death, likely fueled by rumors among the press and disgruntled players. In one imagined scenario, Warfield’s demise was the result of an encounter with a woman in the Bailey Hotel, a conclusion likely drawn from those who adjudged him as a “ladies’ man.”96 These assertions are unsubstantiated but nonetheless are frequently repeated. The truth about Warfield’s death is this: Although no autopsy was performed, the official cause of death was tuberculosis, which, according to his death certificate, he contracted while living in Baltimore. It is not unusual for a person who suffers from tuberculosis to die suddenly from a heart attack.97Warfield’s body was shipped to Maryland where he was buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Baltimore. Evidence of a headstone has yet to be documented. The Pilots sailed on without him for the remainder of the season and named Webster McDonald as the team’s new manager. They finished near the bottom of the standings and disbanded by the end of the season along with the East-West League.

After Warfield’s death, tributes poured in from sportswriters, players, and fans. W. Rollo Wilson, whose harsh opinions of Warfield had softened over the years, paid his respects. Five years before Warfield’s death, Wilson wrote that he considered Warfield one of the greats, on par with Oscar Charleston and Biz Mackey, and lamented that integration in baseball would come too late for all three men.98 Wilson was among the first to jump in to heap praise on the deceased. He noted, “It is significant that when news of [Warfield’s] death was flashed here to Philly all white and colored teams halted their games to pay tribute to him.”99 Wilson added that the “steadying influence of the reliable Warfield at second base always had its effect on any infield in which he worked,” and that “baseball men have paid tribute to his ability and to him as a man, and I would add my name to the list of those who saw in him as an upstanding sports figure and worthy model of our professional athlete.”100 Oscar Charleston remembered Warfield as “a gentleman first, and a ball player next,” and Gus Greenlee agreed when he said that Warfield was the “finest and most gentlemanly players I have ever known.”101 Other tributes described Warfield as “quiet and modest” and noted that, at age 25, he had “surprised the old-timers by turning out a winning team.”102

When Warfield died, his only immediate survivors were his father, Richard Warfield of Indianapolis, and his paternal aunt, Lucy Warfield Leavell, who lived near Pittsburgh. After Frank’s death, his father moved to Pennsylvania to be closer to his sister and her family. Richard Warfield died of lobar pneumonia on February 14, 1938, in a hospital in Homestead. He was buried in the Oak Grove Cemetery in Beaver County, where his sister Lucy Warfield Leavell was buried later that year.

Frank Warfield’s legacy as a player-manager is complicated. His life story has been muddled by journalistic bias, conflicts with players, repeated errors regarding his personal and professional life, and the passage of time. His lifetime batting average of .264 is not overly impressive, but in his time, he was acknowledged as one of the best second basemen in the Negro leagues and as a masterful player-manager.

Warfield showcased his brilliant baseball mind as the youngest player-manager in baseball history to win a “world series.” He was small in stature and slender in build – he stood just 5-feet-7-inches tall and weighed 160 pounds.103 But Warfield made the most of his physique as a tiny terror on the basepaths and was always a threat to stretch a single into extra bases, or to steal another base once he made it to the initial sack.

His extraordinary baserunning talents inspired his nickname, Weasel Warfield, but the use of this nickname by the press was extremely rare during his lifetime. It first appeared in print in 1930, just two years before his death, and in the context of the nose-biting incident between Warfield and Marcell. Later, one sportswriter correctly stated that Warfield’s “pet name was ‘the weasel’ due to the fact that, like his namesake, he was cunning, brainy, and a strategist parexellence [sic].”104 The “Weasel Warfield” nickname most often appeared in print after his death and took on a more negative connotation. This further shaped an increasingly unflattering perception of Warfield, especially when evaluating his worthiness for inclusion in the Hall of Fame. One writer claimed that Warfield rightfully earned the moniker by a reputation as a knife-wielding, overly competitive manager with a “mean streak” and a “vicious temper, who was universally reviled by his players.”105 But this does not tell the whole story. There is no doubt that Warfield was fiercely competitive and a disciplinarian – things he learned from his mentor, C.I. Taylor.106 He very likely did carry a knife, as did many men of his era. It is also true that Warfield was involved in heated arguments with umpires and players – but that did not make him an outlier, particularly in the era in which he played and managed. In fact, poor umpiring was endemic during Warfield’s career, especially during his tenure with Hilldale.107 However, little evidence exists to suggest that it was always Warfield who threw the first punch.

Warfield’s worthiness for the Hall of Fame is up for debate. Many of his teammates, some of whom he managed, are currently in the Hall of Fame. Warfield may never be enshrined at Cooperstown, but his mastery of second base and the basepaths, and his impressive record as one the youngest player-managers in all of baseball history to earn a pennant or world series flag for several different teams makes him worthy of reevaluation and recognition.

Sources

Unless otherwise indicated, all Negro League statistics and records were sourced from Seamheads.com.

Ancestry.com was used to access census, birth, death, marriage, military, immigration, and other genealogical and public records.

Notes

1 Population of Kentucky by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, December 29, 1900, Census Bulletin No. 25, Washington, D.C.: 15.

2 Jack S. Blocker Jr., “Black Migration to Muncie,” Indiana Magazine of History 92 no. 4 (December 1996): 297-320.

3 “Notice,” Indianapolis Freeman, August 3, 1889: 4.

4 Jack Glazier, Been Coming Through Some Hard Times: Race, History, and Memory in Western Kentucky (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2012).

5 “Short Work of Leavell,” Hopkinsville Kentuckian, October 14, 1905: 1; “Gross Insult Avenged,” Kentuckian, October 9, 1906: 1.

6 Leonard J. Moore, Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

7 Kayla Dwyer, “Coalition Gathering Support to Rebuild ‘Inner Loop,’ This Time Underground,” Indianapolis Star, August 24, 2021: A1.

8 “Chum Shot; Boy Runs Away,” Indianapolis Star, June 29, 1910: 26.

9 “Chum Shot; Boy Runs Away”; “Colored Lad Wounded,” Indianapolis Sun, June 30, 1910: 7; “Boy Shot in Shoulder,” Indianapolis News, June 30, 1910: 20.

10 Billy Lewis, “Dennison [sic] Cubs Beat the Canleys [sic],” Indianapolis Freeman, June 28, 1913: 7; “Ellettsville Trims Gosport,” Bloomington (Indiana) Evening News, May 18, 1914: 1.

11 Billy Lewis, “Dennison Cubs Beat the Canleys,” Indianapolis Freeman, June 28, 1913: 7.

12 “The Denison Cubs Won the Game,” Martinsville (Indiana) Reporter-Times, July 21, 1913: 2.

13 “Eastern Black Sox Slaughtered by A.B.C.’s,” Indianapolis Freeman, September 13, 1913: 4.

14 “Look Who’s Coming to Town Sunday,” Alexandria (Indiana) Times-Tribune, August 15, 1914: 1.

15 J.H. Wright, “Indianapolis A.B.C. Defeats Louisville White Sox,” Indianapolis Freeman, July 4, 1914: 4.

16 Wright.

17 Wright.

18 “Semi-Pro. News,” Indianapolis News, June 21, 1915: 11.

19 “Young” Knox, “Gleanings Along the Firing Line,” Indianapolis Freeman, July 10, 1915: 4.

20 “A.B.C.S [sic] Get Even with Louisville White Sox,” Indianapolis Star, July 6, 1915: 9.

21 “A.B.C.S Get Even with Louisville White Sox.”

22 “Johnson Shuts Out Sox,” Indianapolis Star, July 7, 1915: 3.

23 “Taylor Also to Have Club in the Field,” Indianapolis Star, March 20, 1916: 10.

24 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina, 2007), 67.

25 Debono, 77.

26 “Ninth Inning Rally Gives A.B.C.’s Game,” Evansville Courier and Press, June 24, 1917: 8.

27 “Poor Support of Johnson Is Just One Cause,” Muncie (Indiana) Evening Press, September 10, 1917: 8.

28 Debono, 69.

29 Debono, 79.

30 “A.’s [sic] Beat the Aviators in Close Scrap,” Indianapolis Star, July 5, 1918: 10.

31 “Greys’ 1918 Ball Season Probably Ended,” Muncie Evening News, October 11, 1918: 2.

32 “Two Good Games Are Assured Fans,” Muncie Star Press, August 16, 1918: 11.

33 “Soldier-Parcel Plans Advanced,” Indianapolis Star, October 13, 1918: 52; “Red Cross Shipment,” Indianapolis News, October 17, 1918: 12.

34 Debono, 82.

35 “American Giants Give Dayton Marcos Ball Lesson in 7 to 4 Game,” Chicago Whip, September 20, 1919: 8.

36 “Detroit Stars Win in Detroit,” Chicago Whip, April 24, 1920: 6; “Stars Galore with Detroit Colored Team,” Indianapolis Star, July 3, 1920: 13.

37 “Marcos to Play Italians Today,” Dayton Daily News, September 19, 1920: 13.

38 “Redding Misses No-Hit Game,” Brooklyn Times-Union, October 18, 1920: 7.

39 “Baseball,” Palm Beach Post (West Palm Beach, Florida), January 15, 1921: 4.

40 “The Big Teams in 1 to 1 Tie,” Chicago Whip, March 19, 1921: 8.

41 “American Giants Play Local Team at Morris Brown,” Atlanta Journal, March 28, 1921: 12; “Giants Defeat Martins,” Memphis Commercial Appeal, April 11, 1921: 14.

42 “Detroit’s Keystone King,” Chicago Whip, April 9, 1921: 8.

43 “Frank Warfield,” Chicago Whip, July 9, 1921: 8.

44 “Frank Warfield,” Chicago Whip, October 22, 1921: 8.

45 “Sharing Honors with DeMoss,” Chicago Whip, July 8, 1922: 8.

46 “Tigers Drop Two Games to St. Louis Stars,” Chicago Defender, October 14, 1922.

47 “Tigers Drop Two Games to St. Louis Stars.”

48 “Interrace Games Show Class of Race Players, Writer Says,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1933: 8.

49 “Warfield’s Leaving Wrecked Detroit,” Baltimore Afro-American, January 18, 1924: 14.

50 “Warfield’s Leaving Wrecked Detroit.”

51 “John Henry Lloyd Now Manager of Hillsdale [sic],” New York Age, January 27, 1923: 6.

52 “Hilldale President Suspends Manager John Henry Lloyd,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 29, 1923: 6; W. Rollo Wilson, “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 6, 1923: 7.

53 “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul.”

54 “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul.”

55 “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul.”

56 “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul.”

57 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 102-103.

58 “Suspension of Lloyd Made Permanent by Darby Mogul.”

59 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 15, 1923: 7.

60 W. Rollo Wilson, “Through the Eyes,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 11, 1958: 16.

61 Don Burley, “Confidentially Yours,” Little Rock Arkansas State Press, March 30, 1951: 3.

62 “Close to 50,000 Fans Witnessed World Series Games,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 1, 1924: 6.

63 “W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 7, 1925: 7.

64 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 5, 1925: 13; W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 17, 1926: 14.

65 W.O. McGeehan, “Bodie Pilfers Put-Out from Peckinpaugh,” New York Tribune, March 28, 1919: 19; W.O. McGeehan, “Down the Line,” Washington Evening Star, July 6, 1929: 21.

66 Lanctot, 135.

67 Lanctot, 132-133.

68 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida, 2001), 205.

69 W. Rollo Wilson, “Eastern Snapshots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 17, 1926: 14.

70 Lanctot, 147.

71 “Otto Briggs Succeeds Warfield as Captain of Hilldale Club,” New York Age, July 27, 1927: 6.

72 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 29, 1928: 18.

73 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 9, 1929: 12.

74 John Holway, “Baltimore’s Great Black Ball Team,” Baltimore Sun, August 28, 1977: K3; “Baltimore Gets Marcelle and Cason from Atlantic City for Three Players,” New York Age, March 30, 1929: 6.

75 W. Rollo Wilson, “New American League Completes Schedule; All Loop Teams Impress,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 28, 1929: 16.

76 W. Rollo Wilson, “New American League Completes Schedule; All Loop Teams Impress.”

77 W. Rollo Wilson, “New American League Completes Schedule; All Loop Teams Impress.”

78 “Black Sox Player Jailed Following Fight in Cuba,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 8, 1930: 14.

79 “Black Sox Player Jailed Following Fight in Cuba.”

80 “Black Sox Player Jailed Following Fight in Cuba.” Oliver Marcell’s surname was often misspelled as Marcelle.

81 “Black Sox Player Jailed Following Fight in Cuba.”

82 Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 116.

83 Stephen R. Greenes, Negro Leaguers and the Hall of Fame: The Case for Inducting 24 Overlooked Ballplayers (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2020), 87.

84 Bill Gibson, “Here Me Talkin’ to Ya,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 26, 1930: 14.

85 “Black Sox Relying on Suttles’ Bat in Hilldale Contests,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 1, 1930: 37; “Black Sox to Face Only Team to Beath Them This Season,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 6, 1930: 45; “Black Sox Procure Three New Players to Fill Vacancies,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 8, 1930: 25; “Satchells [sic] Returns to Black Sox Fold for Hilldale Bill,” Baltimore Evening Sun, July 31, 1930: 33.

86 “Colored Pro Baseball League to Meet Here,” Washington Post, March 10, 1932: 12.

87 “Pilots Lose Loop Game,” Washington Evening Star, May 20, 1932: 43.

88 “Here Me Talkin’ to Ya,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 25, 1932: 14.

89 “Here Me Talkin’ To Ya.”

90 “Wolves to Meet Revamped Pilots,” Detroit Free Press, June 30, 1932: 17.

91 “Pilots to Be Strong Opponent,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 3, 1932: 12; “Craws Await D.C.,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 23, 1932: 15.

92 “Grays Cop Edge from Pilots,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 9, 1932: 15.

93 “Crawfords Beat Pilots,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 23, 1932: 16.

94 “Seventeen for Crawfords,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 24, 1932: 13.

95 “Frank Warfield, Ball Player, Dies,” Chicago Defender, July 30, 1932: 8.

96 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 817.

97 José Patricio López-López et al, “Tuberculosis and the Heart,” Journal of the American Heart Association, March 18, 2021 Vol. 10 No. 7., https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.019435, accessed November 9, 2021.

98 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 15, 1927: 13.

99 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 6, 1932: 14.

100 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 6, 1932: 14.

101 “Baseball Notables Lament His Passing,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 20, 1932: 15.

102 “Frank Warfield Dies Suddenly in Pittsburgh,” New York Age, August 6, 1932: 6.

103 “Frank Warfield, Ball Player, Dies,” Chicago Defender, July 30, 1932: 8.

104 Alvin Moses, “Beating the Gun,” Kansas City (Kansas) Plaindealer, February 21, 1941: 3.

105 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Frank Warfield,” Center for Negro League Research, 2014, 1, 2; http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Frank-Warfield.pdf, accessed June 1, 2021; Stephen R. Greenes, Negro Leaguers and the Hall of Fame: The Case for Inducting 24 Overlooked Ballplayers, 87.

106 John Holway, “Indianapolis ABCs 1914,” Indianapolis Star, August 25, 1973: 48, 50, 51.

107 Lanctot, 132-133.

Full Name

Frank Warfield

Born

April 28, 1899 at Pembroke, KY (USA)

Died

July 24, 1932 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.