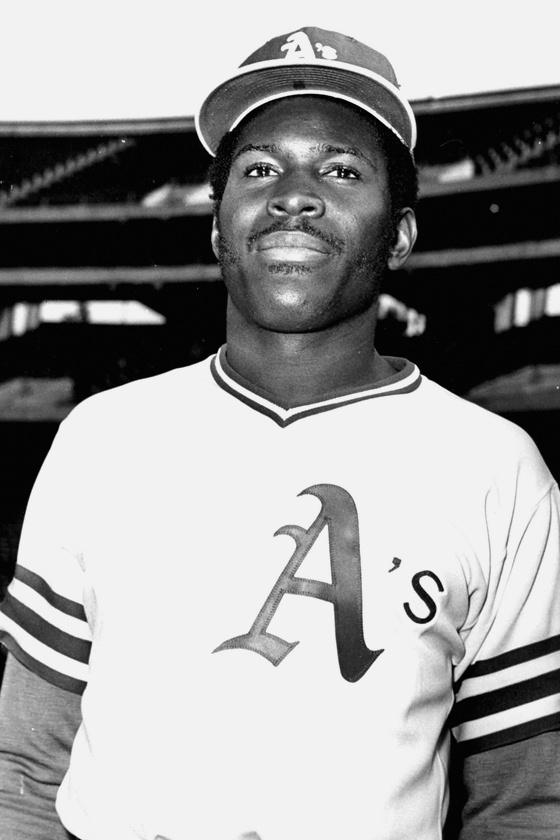

Don Hopkins

Don Hopkins, an outfielder by trade, got into 85 big-league ballgames in 1975 and 1976. He made just eight plate appearances and played 10 innings in the field. Yet he scored 25 runs and stole 21 bases. How did he compile such bizarre statistics? He was the third of Charlie Finley’s “designated runners” with the Oakland A’s. The former high-school track star was built like a racehorse — as A’s beat writer Ron Bergman described him, “at 6-1 and 175 pounds, Hopkins’ legs seem to grow right out of his chest.”1

Don Hopkins, an outfielder by trade, got into 85 big-league ballgames in 1975 and 1976. He made just eight plate appearances and played 10 innings in the field. Yet he scored 25 runs and stole 21 bases. How did he compile such bizarre statistics? He was the third of Charlie Finley’s “designated runners” with the Oakland A’s. The former high-school track star was built like a racehorse — as A’s beat writer Ron Bergman described him, “at 6-1 and 175 pounds, Hopkins’ legs seem to grow right out of his chest.”1

Donald Hopkins — he had no middle name — was born on January 9, 1952, to Frank and Lillie (née Young) in West Point, Mississippi. The Hopkinses were a large family: five sons (in addition to Donald, they were Jimmie, John, Frank Jr., and Brian) and four daughters (Bettie, Bobbie, Lorrie, and Liz). Don was the fifth child.2

A striking parallel connects the lives of Don Hopkins and Herb Washington. Briefly teammates in 1975 as pinch-running specialists, the two men were born less than two months apart in Mississippi. Washington’s family moved to Flint, Michigan, when Herb was around one year old. His parents sought work in the auto plants. When Hopkins was around three, he and his family moved to another city in Michigan, Benton Harbor. They were part of the Great Migration of African-Americans from the rural South to urban industrial centers in other parts of the country. The 1940 census shows Frank Hopkins employed as a farmer. He owned his own property in West Point (as opposed to sharecropping), and there was a nearby street named Hopkins. In Benton Harbor, however, he went to work for a scrap yard as a truck driver. Lillie was a homemaker.3

Insight into Benton Harbor’s black community back then comes from Long Time Coming, the memoir of Chet Walker, a star forward in the National Basketball Association in the 1960s and ’70s. Walker, who’d moved from Mississippi himself in 1950, said that the southerners re-created a sort of village atmosphere. He knew of no rising black middle class, but there was a sense of stability and opportunity. Despite a distance from white society, Walker didn’t feel that he was a member of the underclass or that he’d been left behind.4 Overall, Hopkins felt the same way.5

Young Don began playing baseball at age 10 in Little League.6 In Babe Ruth League, he had another future big-leaguer as a teammate: Dave Machemer, who played 29 games in 1978 and 1979. Their coach was Dave’s father, Bill Machemer.7 Don and Dave also teamed in American Legion ball, playing in Benton Harbor’s Blue-Gray League. One game in particular showed what Hopkins could do: he beat out three infield hits, including what appeared to be a routine tap back to the mound.8

At Benton Harbor High School, Hopkins lettered in four sports. He played tailback in football and was a high-scoring guard on the basketball team. He also starred in track (he was allowed to pursue it as well as baseball in the spring). In August 1968, his path crossed Herb Washington’s for the first time. Visiting Benton Harbor for the Berrien County Olympian Games, Washington — already regarded as a first-rate sprinter — ran an exhibition 100-yard dash in 9.7 seconds. Hopkins, competing in the 16-17 age bracket, won that division.9 He also remembered racing directly against Washington on another occasion in either 1968 or 1969.10

Also noteworthy was the 12th annual Twin City Rotary Meet in May 1969. Benton Harbor High won the 4 x 220-yard relay race convincingly, thanks to Hopkins and Machemer.11 The following June, as the school won the Class A state championship in track, Hopkins placed in four events and ran the 100 in 9.7.12

In baseball, Hopkins raised his average from .313 as a junior to .333 as a senior. He won the Berrien County Sportswriters’ Award as the county’s outstanding senior athlete in 1970. He received 25 scholarship offers from colleges around the country in his four sports. Yet he later said that he didn’t like track and didn’t care for contact sports either — he considered himself a baseball player. Shortly after graduating, he turned pro; the Montreal Expos signed him as an amateur free agent. The scout was Bill Schudlich, who had a long career finding talent with several organizations, especially in the Midwest and Michigan. Schudlich said that Hopkins had exceptional speed and a fair arm, and that if he learned to hit, he could go places.13

In rookie ball with the Gulf Coast League Expos, Hopkins got into just 22 games. The lefty swinger (he threw right-handed) hit .268 in 41 at-bats but stole just two bases. The following year, he began to display his speed with Watertown (South Dakota) of the Class A Northern League. Though he hit only .204 with 64 strikeouts in 191 at-bats, he stole a league-leading 39 bases and was caught just nine times.

Ahead of minor-league spring training in 1972, the Expos scheduled a “school for thieves,” inviting 16 of their fastest farmhands to attend sessions on base running, base stealing, and bunting. Mel Didier, then director of minor league operations for Montreal, said, “We have speed in our minor league system and we want to utilize this to our best advantage. . .this special three-day camp will be a briefing on how to take the most possible advantage of their speed.”14 The most successful of these invitees was Jerry White, but Bombo Rivera and Pepe Mangual also played several years in the majors. Besides Hopkins, another player there also became a “designated runner” for Oakland a few years later: infielder Larry Lintz.

Hopkins split the ’72 season between two Class A teams: Jamestown (New York) in the NY-Penn League and West Palm Beach in the Florida State League. He lifted his average to .259 in 305 at-bats and cut his strikeouts down to 19% of his plate appearances. He got six doubles and four triples, but his absence of power was apparent. Although he had good size and strength, he was encouraged to hit down on the ball to take advantage of his speed, and the approach became ingrained. He also remembered being told to bunt whenever possible. “You did what you had to do,” he observed.15

Hopkins reached base enough in 1972 to steal 66 bases in 76 attempts. He got 63 of those steals with Jamestown, setting a league record.16

To start 1973, Hopkins was promoted to Quebec in the Eastern League (Class AA). Before the season, he set a goal of 100 steals.17 He wound up with 58 in 71 tries, splitting the season between Quebec and West Palm Beach. He might have reached his target if he’d played more (he got into just 85 games) and hit more (just .214 overall, with an on-base percentage of .310).

Hopkins never played winter ball. He briefly attended the University of Toledo in the 1973-74 offseason, having won a scholarship. He played football, but Mel Didier encouraged him to come back and play baseball, saying that they’d work something out.18

In his fifth year as a minor-leaguer, 1974, Hopkins made it up to Triple-A, albeit for just eight games. He spent the bulk of the season back in Class A, with Kinston (North Carolina) of the Carolina League. However, he also returned to Quebec for 12 games. He stole 59 bases overall and was thrown out just seven times. He posted a career-high batting average of .286 overall.

At that time, however, the Expos system was loaded with highly talented young outfielders ready to emerge: André Dawson, Ellis Valentine, and Warren Cromartie. Near the end of March 1975, Hopkins got his big break when Oakland purchased his contract from Montreal. Charlie Finley had hoped to acquire Sheldon Mallory, then a Kansas City Royals farmhand, who’d stolen 81 bases in 1974, mainly at Class A. Apparently, however, the Royals were considering putting Mallory on their roster as a pinch-runner — so the search for speed widened.19

Hopkins didn’t hear directly from Finley when the deal was made; he met him first at Oakland’s spring training site in Arizona (the Expos trained in Florida).20 He was assigned uniform #1 (worn for the previous 11 seasons by Dick Green, who’d retired).21 To make room for “Hoppy,” the team released veteran outfielder Jesús Alou. Finley proclaimed, “We’re going to keep both [Hopkins and Washington]. These two pinch-runners are going to help us as our 24th and 25th players. … We used to pitch teams to death and now we’re going to run and hit them to death.” Manager Alvin Dark toed the company line, though Sal Bando shook his head in disbelief. Finley’s sarcastic response was, “I don’t know what the manager’s committee will say. You know, the players on the team who think they run the club.”22

“I questioned it,” Washington said of the Hopkins deal. “Then I said maybe we can.”23 Indeed, Finley had also said that the two players were not in competition and that one would complement the other.24

But then, on April 28, Oakland also acquired Matt “The Scat” Alexander in a minor-league deal with the Chicago Cubs. Alexander was another very speedy man who could play both the infield and the outfield, and he wasn’t a bad hitter. Reggie Jackson said, “We’ve got these two new guys — Alexander and Hopkins — and they can do other things, plus they run the bases better than Washington.”25 Though Washington was a world-class track man, he’d had zero pro baseball experience before coming to the A’s in 1974.

“When they got Matt Alexander,” said Washington, “there was no way. Not three runners.”26 Actually, the trio did play together briefly: all appeared in extra-innings games on May 2 and 3. Washington made his final big-league appearance on May 4. The next day he was released. “We’ve got to have pinch-runners who can steal bases and also do some other things,” said Finley.27

Hopkins was not aware at the time of the family background he shared with Washington; he said that they didn’t interact very much in the time their careers overlapped. Claudell Washington (then just 20) became his road roommate and good friend. His two other closest friends on the club were Mike Norris and Jim Holt.28

Over the course of the 1975 season, somehow Dark found a way to get Hopkins into 82 games and Alexander into 63 (Alexander suffered a shattered eye socket in early June from a batting-practice grounder and missed a month). Between them, they totaled 19 plate appearances, of which Hopkins had eight; he was 1-for-6 with two walks. His only hit in the majors was a single off Detroit’s Fernando Arroyo in a 16-4 laugher at Tiger Stadium on July 22.

Of course, the job Hoppy was paid for was to steal bases, and he swiped 21 in 30 attempts. However, he was successful on only 15 of his first 24 tries. In a Sports Illustrated feature that June, he noted that he hoped to improve his percentage as his knowledge of the pitchers increased. Teammate Bill North, one of the league’s top base thieves, made another point: everybody in the ballpark knew that certain A’s would be running. North said it wasn’t base stealing, which connoted surprise — it was base taking.29

In early August, Hopkins was sent down to Triple-A Tucson in the Pacific Coast League as pitcher Sonny Siebert was activated from the disabled list. For a few weeks, at least, the A’s viewed having another arm as more valuable than a second running specialist; they also kept pitcher Glenn Abbott on the roster.30

At Tucson, Hopkins hit .259 in 24 games — including his only home run in professional baseball, a fluke inside-the-parker. It came in the first game of a doubleheader at Salt Lake City’s Derks Field on August 16. In the first inning, he hit a fly to medium right field. Gulls right fielder Gil Flores lost the ball, thought it was hit harder than it was, and raced back to the fence. By the time center fielder Rusty Torres had picked it up, Hopkins had circled the bases standing up. In that twinbill, he went 7-for-9 with four RBIs while scoring five runs.31

Oakland flew Hopkins in from Tucson for a day to take his place in the team picture — rather surprising, in view of Finley’s penny-pinching.32 The team then recalled him as a player before the end of August.33 Thus, he was eligible for the playoffs against the Boston Red Sox, although heading into the ALCS, Oakland had deactivated him.34 Just before the opening game, however, the A’s dropped catcher Larry Haney because of a sore right arm. With the permission of league president Lee MacPhail, Hopkins replaced Haney.35 According to Hopkins, Finley had invited him to sit in the owner’s box but then decided to make the last-minute move. Haney might not really have been injured.36

As a result, both Hopkins and Alexander were on the postseason roster. Hopkins got the lone appearance between them as Boston swept the series in three games. Oddly enough, it was as a pinch-hitter; batting for Billy Williams, he made the second to last out of Game One, grounding into a force play against Luis Tiant.

A few weeks after the ’75 season ended, Oakland obtained Larry Lintz from the St. Louis Cardinals. Like Hopkins, Lintz had no power, though he had two-plus seasons of big-league experience as a middle infielder. During spring training 1976, he joined Alexander and Hopkins to compete for the running specialist jobs. It was remarkable enough that Finley (in his capacity as general manager) still devoted two roster slots to such players, yet again the possibility lingered that it might even be three. During spring training, Ron Bergman wrote, “Not all three are expected to stick, but with the speed-crazy Finley at the helm, no one knows for sure.”37

Lintz got the nod over Hopkins once his sore arm and leg got better.38 According to Hopkins, there was not a rivalry among him, Lintz, and Alexander. He was sent down largely because the team had options on him that it could use.39

Back at Tucson, Hopkins went .264-0-18 in 98 games, with 42 steals in 51 attempts. He was briefly recalled toward the end of May but did not get into a game. It was rich to observe that when he was sent back down, the reason given was roster balance.40

That September, Hopkins was recalled again, and he made his final three big-league appearances. Sure enough, all were as a pinch-runner. He was forced out twice and caught stealing the other time by Chicago’s Wayne Nordhagen, who seldom played catcher in the majors. When asked about the toughest opposing catchers he faced, Hopkins named Jim Sundberg of the Texas Rangers — seconding Matt Alexander’s opinion — along with Thurman Munson of the Yankees.41

Not long after the ’76 season ended, Hopkins’ hometown newspaper, the Benton Harbor News-Palladium, interviewed him. He looked forward to the upcoming AL expansion draft, thinking that both new clubs, Seattle and Toronto, would be looking for speed. He thought that he’d had a “pretty decent season” at Tucson and shown the scouts what he could do. He was working during the offseason as a security guard at Benton Harbor High School. Though his friends on the A’s had tried to get him to stay in Oakland, he liked Benton Harbor because he had a lot of friends there, as well as his mother. Still just 24, he hoped that he had many years ahead in baseball. He expressed a goal of getting in enough time for his pension (the minimum then was four years). He concluded by saying, “Just being in the big leagues at all is a dream come true. Even if I don’t play any more, at least I can say I made it.”42

Neither expansion team selected Hopkins, and 1977 turned out to be his last season in pro baseball. Again the A’s had two pinch-running specialists on their bench, but again they were Alexander and Lintz. It’s also noteworthy that Oakland had finally acquired Sheldon Mallory, who played his only season in the majors in ’77, mainly in the outfield but with 17 pinch-running appearances, too.

Hopkins went to the team’s new top farm club, the San José Missions. He got into just 37 games, going .214-0-8. He missed some time with a broken arm and was released around midseason. He thought about playing in Mexico; in fact, old friend Mel Didier, who by then had become scouting director for Seattle, had lined up an opportunity for him there. But when Hopkins called the number he’d been given, he kept getting a busy signal, so he gave up.43

Even so, he still kept his dream alive as late as July 1978. At Bailey Park in Battle Creek, Michigan, he took part in one of five tryout camps in the Michigan-Indiana-Ohio area conducted under the auspices of the Major League Scouting Bureau. Scouts Jim Martz, Dick Colpaert, and Joe Morlan looked over 117 hopefuls. Hopkins could still run the 60-yard dash in 6.5 seconds, and he was one of the few whose arm was rated 4 on a scale of 2 to 8 (5 being major-league average). The article noted, however, that the chances of getting signed out of such camps were very slim — maybe only two players out of the lot would rate even a “follow-in” report.44

Hopkins continued to live in Benton Harbor after quitting pro ball. While he was still an active player, he’d enjoyed playing in a recreational men’s basketball league there during the off-seasons. One photo from the News-Palladium in November 1977, which showed him brushing snow from his car, said that he preferred Michigan snow to California rain.45

On December 17, 1977, Hopkins married Robin Hudson, who came from Benton Harbor as well. He adopted her child from a prior relationship, a son named Parrish. That was the first of his three marriages. The second was to Grishondra Westfield, also of Benton Harbor. At various times, Hopkins lived in Cincinnati, Tulsa, Indianapolis, and Lansing. He worked in sheriff’s departments and as a truant officer. Around 2005, he came back to Benton Harbor because his daughter from his second marriage, Ashdon, was there. He coached football, baseball, and basketball.46

Hopkins did not get in enough service time to become vested in Major League Baseball’s pension plan; his career predated 1980, when the requirement was reduced to 43 days but was not made retroactive. Thus, he is one of the hundreds of men who receive merely the modest annual payments to non-qualified players of $625 per quarter of service, which took effect in 2011. His awareness of the issue was evident because he mentioned the name of Steve Rogers, who was in the Expos chain at the same time as he in the early ’70s and went on to become the players’ pension liaison.47

Yet despite this inequity, Don Hopkins is still pleased to have played in the majors. Looking back at his career, he said with a chuckle, “They said I couldn’t hit. Well, I pinch-hit for some of the best, like Billy Williams, and against some of the best, like Ferguson Jenkins. The whole experience was exciting to me.”48

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Don Hopkins for his input (telephone interviews, March 1 and March 5, 2018, plus e-mails). Thanks also to SABR member Alain Usereau for material from his files.

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Ron Bergman, “Happy Charlie Does Jig Over Hippity-Hoppy,” The Sporting News, April 19,1975, 5.

2 “Lillie Hopkins,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, April 17, 2001. Telephone interview, Don Hopkins with Rory Costello, March 1, 2018 (hereafter “Hopkins interview #1”).

3 Ibid. E-mail from Don Hopkins to Rory Costello, March 2, 2018.

4 Chet Walker with Chris Messenger, Long Time Coming, New York: Grove Press (1995): 14, 22, 25, 26, 35.

5 Hopkins interview #1.

6 Ibid.

7 “BRL Rosters Set,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, May 3, 1965, 43.

8 Jim DeLand, “BH Post 105, Dyer Slam Berrien, 10-2,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, June 28, 1969, 13.

9 “Washington Runs Torrid 9.7 Century,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, August 26, 1968, 15. Hopkins remembered the encounter in 1975. Jay Coleman, “A’s employ second run specialist,” Arizona Republic, April 1, 1975.

10 Hopkins interview #1. Bergman, “Happy Charlie Does Jig Over Hippity-Hoppy.”

11 Jim DeLand, “Tiger Baseballers Steal Rotary Show,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, May 20, 1969, 14.

12 “Superb Track Campaign Ends,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, June 3, 1970, 23.

13 “Hopkins Picks Pro Baseball Career,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, June 27, 1970, 14. Coleman, “A’s employ second run specialist.”

14 Ian MacDonald, “Florida School for Thieves Latest Expo Innovation,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1971.

15 Hopkins interview #1.

16 Tom Boggie, “Baseball No Waiting Game for Ted] Wilborn,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1978, 52.

17 “Watch Out for Thief,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1973, 38.

18 Hopkins interview #1.

19 “Washington Has a Running Mate,” San Mateo Times, March 29, 1975, 19.

20 Hopkins interview #1.

21 After Hopkins no A’s player wore #1 again until Nomar Garciaparra in 2009.

22 Bergman, “Happy Charlie Does Jig Over Hippity-Hoppy.”

23 “A’s Cut Herb Washington; Roger Nelson Joins Club,” United Press International, May 6, 1975.

24 “Washington Has a Running Mate.”

25 Ron Bergman, “Loss of Catfish [Hunter Hastened Herbie’s Farewell,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1975 ,13.

26 “A’s Cut Herb Washington; Roger Nelson Joins Club.”

27 “Washington Eyes Return,” Associated Press, June 13 ,1975.

28 Hopkins interview #1. Ron Bergman, “A’s Discover Mr. Kleen in SuperWash,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1975, 3.

29 Ron Fimrite, “It’s a Game of Pinches,” Sports Illustrated, June 30, 1975.

30 Ron Bergman, “Claiborne Quits A’s as Finley Yawns,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1975, 18.

31 “Hopkins Helps Tucson,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1975, 38. “’Last hope’ puts Toros into first,” Tucson Daily Citizen, August 18, 1975, 27.

32 Ron Bergman, “Injury to Joe] Rudi’s Thumb Darkens A’s Prospects,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1975, 36.

33 “A’s Activate Dal Maxvill,” United Press International, August 31, 1975.

34 “Joe Rudi Doubtful, but Still on Roster,” Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times, October 1, 1975, 33.

35 “A’s Catcher Off Roster,” Detroit Free Press, October 5, 1975, 14.

36 Hopkins interview #1.

37 Ron Bergman, “Young [Mike] Norris Key to A’s Pitching Staff,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1976, 16.

38 Ron Bergman, “Don] Baylor to Feel Heat Trying to Fill Reggie [Jackson]’s Big Shoes,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1976, 19.

39 Hopkins interview #1.

40 John Mickey, “Ailing [Bill] North helps A’s injure Twins,” Fremont (California) Argus, May 28, 1976, 17.

41 Hopkins interview #1. Matt Alexander, telephone interview with Rory Costello, June 28, 2009.

42 Jack Walkden, “Hopkins Hopes to Crack Majors for Good,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, October 27, 1976, 23.

43 Hopkins interview #1.

44 John Wilhelm, “Players flock to pursue dream of career in big leagues,” Battle Creek Enquirer, July 2, 1978, 29.

45 “Better Than Rain,” Benton Harbor News-Palladium, November 28, 1977, 3.

46 Hopkins interview #1. Telephone interview, Don Hopkins with Rory Costello, March 5, 2018 (hereafter “Hopkins interview #2”).

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

Full Name

Donald Hopkins

Born

January 9, 1952 at West Point, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.