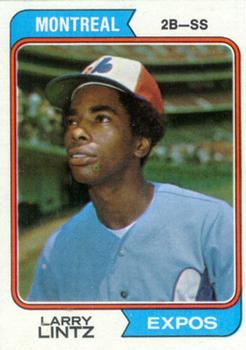

Larry Lintz

Larry Lintz was built like a whippet — 5-foot-9 and 150 pounds — and ran like one. He came up as a middle infielder with the Montreal Expos in 1973 and stole 50 bases the following season, his most active year in the majors. In addition to being an exciting baserunner, he was a good fielder and drew a lot of walks. However, he hit just .227 with a .252 slugging percentage at the top level. That overshadowed the value of his on-base percentage, a statistic that didn’t get much attention in the ’70s. Therefore, he became a specialist — he appeared as a pinch runner in 140 of his 350 games. Lintz is mainly remembered today as the fifth of Charlie Finley’s “designated runners” with the Oakland A’s.

Larry Lintz was built like a whippet — 5-foot-9 and 150 pounds — and ran like one. He came up as a middle infielder with the Montreal Expos in 1973 and stole 50 bases the following season, his most active year in the majors. In addition to being an exciting baserunner, he was a good fielder and drew a lot of walks. However, he hit just .227 with a .252 slugging percentage at the top level. That overshadowed the value of his on-base percentage, a statistic that didn’t get much attention in the ’70s. Therefore, he became a specialist — he appeared as a pinch runner in 140 of his 350 games. Lintz is mainly remembered today as the fifth of Charlie Finley’s “designated runners” with the Oakland A’s.

Lintz was born on October 10, 1949, in Martinez, California. This town 25 miles northeast of San Francisco is best known in the baseball world as the birthplace of Vince and Joe DiMaggio. Little information about Lintz’s parents and siblings has come to light. The California Birth Index shows that his mother’s maiden name was Malone.

Young Larry began playing baseball at age nine.1 He attended Castlemont High School in Oakland and was a second-team All-City selection at second base in 1967. Despite his speed, he did not run track. He later said the last time he did it was in junior high, and that he had no idea what his time would be in the 100-yard dash — he never tried it because it was too long.2

Lintz then went to Laney College, a community college, also in Oakland. One of his baseball teammates there was Lee Lacy. Around this time, he also gained experience playing with the Alameda Braves, a semipro club, and in American Legion ball.3

His next stop was San José State University, where he studied physical education and played baseball in 1970 and 1971. He noted that his coach with the Spartans, Gene Menges, never let the team run, even though there were three players on the team who were even faster than Lintz.4 That wasn’t entirely true; Lintz stole 17 bases in his first season and then set a school record with 34 in 1971, when he also served as team captain. His mark was broken in 1983 but still remains second in the program’s history. That year he was the first-team All-Star second baseman in the Pacific Coast Athletic Association (now the Big West Conference). Other members of that team included Bob Apodaca (Cal State, Los Angeles) and Dick Ruthven (Fresno State).

The Expos selected Lintz in the sixth round of the amateur draft in June 1971. The signing scout was Al Ronning.5 Lintz was assigned to Watertown (South Dakota) in the Northern League (Class A). His main position became shortstop. That summer, he got his first of only two home runs in pro baseball. Pinch-hitting for Dan Warthen in the bottom of the ninth, he ended the game with a two-run shot over the left field wall.6 Lintz hit .280 and stole 25 bases in 65 games, despite being hampered by a leg injury that he sustained in the second game of the season. Yet his most notable statistic was his .495 on-base percentage, fueled by 87 walks. He was named team MVP.

Before minor-league spring training in 1972, the Expos scheduled a “school for thieves,” inviting 16 of their fastest farmhands to attend sessions on base running, base stealing, and bunting. Mel Didier, then director of minor-league operations for Montreal, said, “We have speed in our minor league system and we want to utilize this to our best advantage . . . this special three-day camp will be a briefing on how to take the most possible advantage of their speed.”7 The most successful of these invitees was Jerry White, but Bombo Rivera and Pepe Mangual also played several years in the majors. Besides Lintz, another player there also became a “designated runner” for Oakland a few years later: outfielder Don Hopkins.

Lintz later said that the special lessons definitely helped him because he began to think about getting the most out of his abilities.8 Advancing to Class AA, he continued to play short for the Quebec Carnavals of the Eastern League (EL). His batting dropped off to .226 (a natural righty hitter, he began switch-hitting that season). Yet he continued to display an excellent eye, drawing 110 walks. Setting himself up with a .387 on-base percentage, he stole 96 bases, shattering the EL record set by Dave Mann in 1958.9 He was caught just 11 times.

Toward the end of that season, Carnavals manager Karl Kuehl said of Lintz, “He must improve his hitting and he needs a little more experience, but I would say that he is only one or two years away from the big time.” Kuehl’s projection proved conservative. The skipper added that Lintz was a good fielder who was constantly improving, and that he coupled great instinct with a good knowledge of the game.10

After being named an EL All-Star, Lintz was promoted again in 1973. With Montreal’s top farm club, Peninsula in the International League, he hit just .190 in 76 games, though he still reached base at a very respectable rate (.352). In that half-season, he stole 48 bases, and opposing catchers threw him out just nine times. A Sporting News feature that July called Lintz “the most feared 145-pound, .196 hitter in baseball.”11

That article appeared shortly after the Expos had called Lintz up to the majors for the first time. He was needed as a reserve after starting shortstop Tim Foli suffered a broken jaw. He was “ballyhooed for his speed,” as a Cincinnati Enquirer report observed about a week after his debut. Indeed, his opposite number with the Reds, Dave Concepción, suffered a season-ending broken leg on July 22 while trying to prove a point to Lintz about his prowess on the basepaths.12

When second baseman Ron Hunt went down with a knee injury on August 8, Lintz slid over to fill in there. He had a surprisingly good batting average for a while, with 15 hits in his first 39 at-bats (.385). The rookie credited long hours with batting coach Larry Doby — he said he’d never gotten that kind of help before.13

Lintz remained with Montreal for the rest of the ’73 season, during which the team and its fans experienced the excitement of a pennant race for the first time. On September 17, the Expos briefly climbed into a virtual tie for first. They then faded out of the race but were not mathematically eliminated until losing their final game on Sunday, September 30. On September 26, as Montreal scored four runs in the first inning off Tom Seaver, Lintz provided a spark with one of the game’s rarities: a bunt double. After Mike Jorgensen led off with a walk, Lintz punched a bunt over the head of third baseman Wayne Garrett, who had charged in too far, too fast. By the time shortstop Bud Harrelson picked up the ball in short left, Jorgensen had made third and Lintz second.14 It was his lone extra-base hit for Montreal that year. The Expos eventually won, 8-5.

Lintz played winter ball in Puerto Rico during the 1973-74 season. Early in the season he was hitting a surprising .330, leading the league in runs scored and steals, and making all the plays at second base for the Ponce Leones. Commenting on who might start at second for the Expos in 1974, general manager Jim Fanning said, “Don’t write Jim] Cox off. It’s just that Lintz has jumped surprisingly ahead.”15 He wound up hitting .296 — including his only other professional homer — and his on-base percentage was well above .400.16 He stole 25 bases; the runner-up was Mickey Rivers with 20.

For 1974, Hunt moved over to third base. Cox — who’d been Lintz’s double-play partner in the minors — played the most at second of any Montreal player that year, although he was sent down in early July. Lintz started 55 games at second and 24 at short, appearing in 113 altogether. He hit .238-0-20 in 319 at-bats. Oddly enough, the natural righty batter wound up hitting much better swinging lefty in the majors. This could well be related to something his 1975 Topps baseball card mentioned: that he often beat out choppers. Lintz’s 50 steals in a part-time role were a new club record (although it was just the franchise’s sixth season); he earned comparisons to Maury Wills and Lou Brock.17

Expos beat writer Ian MacDonald of the Montreal Gazette wrote a column entitled “Lintz’ speed key factor in Expos’ future plans.” The article quoted manager Gene Mauch: “Larry Lintz is going to think that I’m following him next spring. He’s going to think I’m in his hip pocket — or he’s in mine.” Mauch said that Lintz had the tools to become a fine ballplayer and that he would be working on his game in winter ball. In particular, the skipper wanted Lintz to make his good bunting even better.18

The article also included a view from “Trader Frank” Lane, the longtime general manager, by then a Texas Rangers scout. Lane called Lintz “an exciting little fellow…he makes things happen.” MacDonald concluded by conveying Mauch’s belief that with a little sophistication, Lintz could become a whole lot more than a marginal player.19 One also wonders whether weight training could have been beneficial had his career started several years later.

As Mauch had indicated, Lintz returned to Ponce for the 1974-75 winter season. His 12 steals were good for second in the league behind Ken Griffey Sr. However, his average dropped off to .202. In spring training 1975, Mauch called Lintz “the best player in baseball once he gets to first base.” One might interpret that remark as a dig at Lintz’s hitting, but Mauch specifically observed that his second baseman’s 88% stealing percentage in 1974 was better than those of the NL’s most notable base thieves: Joe Morgan (83%), as well as Brock, Davey Lopes, and César Cedeño (all at 77%).20

Lintz himself said that he had competition and had to be on his toes. He added, “I either do the job or pay the consequences, which is spend the summer picking splinters out of my [butt].”21 Indeed, near the end of camp, he hurt his left knee and started slowly. Montreal platooned him at second with Pete Mackanin, obtained in the December 1974 trade that sent Willie Davis to Texas. In early May, Ian MacDonald observed that Lintz appeared to tire defensively when used every day. He added that the knee problem was a day-to-day mystery and that it prevented Lintz from running straight ahead “with his usual abandon.” Gene Mauch said, “Lintz, without his speed, is not Larry Lintz.” At that time, Mauch still thought his team was stronger with the platoon.22 By the end of May, however, Mackanin held the job outright. On July 25, Montreal traded Lintz to the St. Louis Cardinals for Jim Dwyer. Lintz was gracious toward Mackanin when he got the news and also looked forward to a renewed opportunity.23

Lintz got into 27 games as a Cardinal over the remainder of 1975, getting just 21 plate appearnces. In a harbinger of his future, St. Louis used him mainly as a pinch-runner. Near the end of October, he was traded to Oakland for Charlie Chant. He viewed joining the A’s as his greatest thrill in baseball to that point.24

By one account, Lintz was dealt because he vetoed a request to go to the Florida Instructional League to work on his hitting and bunting.25 Yet it’s also quite likely that Charlie Finley, who had long been infatuated with speedy runners, simply coveted Lintz and wanted to add him to his group of “rabbits.”

A little background on the history of “designated runners” is in order. For parts of six seasons from 1967 through 1973, Oakland had Allan Lewis, an outfielder by trade, on its roster. “Mr. Finley’s called me up every time,” said Lewis in 1973. “No reports, no scouts, no managers — just him.”26 “The Panamanian Express” was finished as a player after the ’73 season; in March 1974, Finley signed world-class sprinter Herb Washington to be Oakland’s new pinch-runner deluxe, even though Washington had zero pro baseball experience.

Near the end of spring training in 1975, the A’s bought the contract of Don Hopkins from Montreal. Finley proclaimed that the team would keep both Hopkins and Washington on the roster. Then, on April 28, Oakland also acquired Matt “The Scat” Alexander in a minor-league deal with the Chicago Cubs. Alexander was another very fast man who could play both the infield and the outfield, and he wasn’t a bad hitter. Strange as it may seem, especially in today’s era of 13-man pitching staffs, the trio did play together briefly before Washington was released in early May.

Somehow, manager Alvin Dark found a way to get Hopkins into 82 games and Alexander into 63 during the 1975 season. In 1976, however, Lintz replaced Hopkins — though again there was an element of doubt. During spring training, A’s beat writer Ron Bergman said, “Not all three are expected to stick, but with the speed-crazy Finley at the helm, no one knows for sure.”27 Lintz got the nod once his sore arm and leg got better.28 Hopkins also had options remaining.

Hopkins was briefly recalled toward the end of May but did not get into a game — it was rich to observe that when he was sent back down, the reason given was roster balance.29 He made his final three big-league appearances in September and October 1976.

The A’s viewed Alexander as the most complete player among their specialists, yet he got into just 61 games in 1976, whereas Lintz played in 68. For the season, he went to the plate just four times, with two walks, a sacrifice, and a groundout. He appeared eight times in the field. He stole 31 bases — a good chunk of the team’s 341 for the season, still a record in the modern era — and got caught 11 times. It would be interesting to know whom Lintz found to be the toughest opposing catchers he faced.

Lintz also scored 21 runs, and his speed made a difference in several games. For example, on May 16 he scored the winning run in the eighth inning, taking third on a wild pickoff throw and then coming in on a wild pitch. He also scored the winning runs on May 27 and August 12. On June 4, his eighth-inning run tied a game that Oakland won in the 11th. Each time he set it up by stealing second. On July 23, he broke a scoreless tie in the seventh, coming home on a single by Bill North after going from first to third on a sacrifice bunt. Oakland won 2-0.

There was a curiosity about how Finley’s pinch-runners were used. The team had two older designated hitters: Billy Williams (aged 37 at the start of the season) and Willie McCovey (38 and with creaky knees) when the A’s acquired him at the end of August). With some frequency, if they reached base, they would be lifted for a runner, who then assumed the position of DH. The runner was usually replaced in turn before coming to bat, but Alexander got three plate appearances as a DH in 1976, and Lintz got two.

Lintz spent a short stretch of the ’76 season at Triple-A Tucson. César Tovar, who’d broken a bone in his right wrist on May 31, had recovered about a month later yet remained on the disabled list. Tovar complained to Players Association director Marvin Miller, and was removed from the DL in August. When Lintz got the news that he’d been optioned to make room for Tovar, it prompted a shouting match in the clubhouse with manager Chuck Tanner.30 However, Lintz returned toward the end of August. On August 25, Finley — in a typical and possibly vengeful move — had released Tovar.31

After the 1976 season, the A’s were gutted by the loss of five key team members to free agency. Along with third baseman Sal Bando, left fielder Joe Rudi, closer Rollie Fingers, and catcher-first baseman Gene Tenace, Oakland lost Bert Campaneris, the starting shortstop since 1965. Going into spring training, Finley played hardball with unsigned players — he didn’t want anyone else to play out his option and become a free agent. He traded some members of the group, the most notable being Phil Garner. He also sent three others, including Lintz, to the A’s Triple-A camp.32 Lintz had hopes of winning Campy’s shortstop job in 1977, but it went to Rob Picciolo. Nonetheless, he was on Oakland’s Opening Day roster, again beating out Hopkins.

In April, Lintz got a nine-game trial as the starting second baseman. He played excellent defense, but the experiment ended because he was just 3-for-27 (.111) with 12 strikeouts in that span, which apparently masked his eight walks.33 Thereafter he returned to his pinch-running role, though he did appear on occasion in the field (the A’s had obtained Marty Perez to start at second).

In mid-June, Oakland sent Lintz down to its new top affiliate, San José (also in the PCL). He got into 35 games with the Missions, hitting .270 with a .405 on-base percentage and 18 steals. The A’s recalled him when rosters expanded that September. He got in enough roster time to qualify for his big-league pension, as the minimum then was four years.34

Oakland released Lintz on March 30, 1978. The very next day, the A’s also cut Matt Alexander. It’s not entirely clear why Finley, in his capacity as general manager, became disenchanted with pinch-running specialists.

The A’s did employ one more player of this type: Darrell Woodard, a second baseman who came up in the Oakland chain at the same time as the all-time king of stolen bases, Rickey Henderson. Woodard got into 33 games from August through October 1978, of which 22 were just as a pinch-runner.

In mid-May, Lintz signed as a free agent with the Cleveland Indians. He got into three games for Cleveland, all as a pinch-runner. In his first, on May 19, he helped ignite a game-winning three-run rally in the eighth inning with a steal. The next day, however, he was caught stealing in the ninth with the Indians trailing 2-1. His last appearance in the majors came 10 days later, and again he was caught stealing. When Horace Speed came off the DL in early June, Lintz was sent down to Portland in the PCL. There he hit .285 in 50 games; 32 walks lifted his OBP to .429.

Lintz’s pro career concluded in 1979 with three games for Tacoma, yet another PCL team, which had become Cleveland’s top farm club.

Lintz has kept a low profile since his baseball career ended. He does not appear to have remained involved with the game. From his unions with Shirley Brookins35 and Sabrina Lafleur, he had three children named Lateefah, Evonna, and Leondre. He lives in the Sacramento area.

Last revised: October 13, 2021

Acknowledgments

Thanks to SABR member Alain Usereau for material from his files.

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Jan Finkel and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Puerto Rican Winter League statistics: courtesy of SABR member Jorge Colón Delgado, official league historian.

San José State Baseball Media Guide, 2010 (http://grfx.cstv.com/photos/schools/sjsu/sports/m-basebl/auto_pdf/2009-10/misc_non_event/2010-m-basebl-media-guide.pdf)

Big West Conference Baseball Media Guide, 2010 (http://www.bigwest.org/sports/baseball/mediaguides/2010/media.pdf)

Notes

1 Louis Fusk, “Expos’ Farmhand Lintz Rated King of Thieves,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1972: 38.

2 Fusk, “Expos’ Farmhand Lintz Rated King of Thieves.”

3 William J. Weiss questionnaire, date stamp December 26, 1975. Available via ancestry.com.

4 Bob Dunn, “Expos Find a Theft Artist in Swifty Larry Lintz,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1974: 20. It’s also of note that this school was then famed for its outstanding track and field program, known as “Speed City.” Again, however, it does not appear that Lintz went out for track in college.

5 Weiss questionnaire.

6 “Class A Leagues,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1971: 43.

7 Ian MacDonald, “Florida School for Thieves Latest Expo Innovation,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1971: 37.

8 Jim Haynes, “Montreal Has the Thief, Now Hopes to Steal the Flag,” Orlando Sentinel, March 16, 1975: 80.

9 “Lintz Running Wild,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1972: 39.

10 Fusk, “Expos’ Farmhand Lintz Rated King of Thieves.”

11 Bob Moskowitz, “Low Average No Barrier for Base-Stealing Lintz,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1973: 39.

12 Jack Murray, “’I’m Not Going to Steal Bases Any More,’” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 24, 1973: 27.

13 Ian MacDonald, “Pepe] Frias and Lintz Bridge Expos’ DP Gap,” The Sporting News, September 8, 1973: 16.

14 Dick Brinster, “Mets’ Lead Reduced to Half-Game as Expos Snap 7-Game Win Streak, Asbury Park (New Jersey) Press, September 27, 1973.

15 Ian MacDonald, “Barry] Foote candidate to start for Expos, Montreal Gazette, November 15, 1973:34.

16 He had 226 at-bats, 67 hits, and 51 walks, which results in an OBP of .426. Hit by pitch number is not available.

17 Bob Dunn, “Go-Go Expos Pull off Late Wholesale Heists,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1974: 14.

18 Ian MacDonald, ““Lintz’ speed key factor in Expos’ future plans,” Montreal Gazette, October 18, 1974: 23.

19 MacDonald, ““Lintz’ speed key factor in Expos’ future plans.”

20 Haynes, “Montreal Has the Thief, Now Hopes to Steal the Flag.”

21 Haynes, “Montreal Has the Thief.”

22 Ian MacDonald, “Mackanin ‘nice’ problem for Expos brass,” Montreal Gazette, May 9, 1975: 27.

23 Bob Dunn, “Expos Go with Mackanin, Show Exit to Lintz,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1975, 25.

24 Weiss questionnaire.

25 Neal Russo, “’Can Still Do Job, Don] Kessinger Assures Cardinals,” The Sporting News, November 15, 1977: 37.

26 Ron Bergman, “The Freakish Role of Allan Lewis,” Oakland Tribune, March 25, 1973: 24.

27 Ron Bergman, “Young Mike] Norris Key to A’s Pitching Staff,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1976: 16.

28 Ron Bergman, “Don] Baylor to Feel Heat Trying to Fill Reggie [Jackson’s Big Shoes,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1976: 19.

29 John Mickey, “Ailing North helps A’s injure Twins,” Fremont (California) Argus, May 28, 1976: 17.

30 Ron Bergman, “Catcher Tenace Can Drive a Hard Bargain,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1976: 7.

31 Ron Bergman, “A’s More Flexible with Willie [McCovey],” The Sporting News, September 18, 1976: 34.

32 Tom Weir, “Either Sign or Be Seated, Charlie Informs Balky A’s,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1977: 8.

33 Tom Weir, “Trader Finley Swaps Headaches, Mike] Torrez for Dock] Ellis,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1977, 17.

34 Tom Weir, “Ump’s Tips Put Matt] Keough on Course,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1977: 18.

35 California marriage records show their wedding date as October 7, 1972. Lintz’s Sporting News contract card gives the year as 1973.

Full Name

Larry Lintz

Born

October 10, 1949 at Martinez, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.