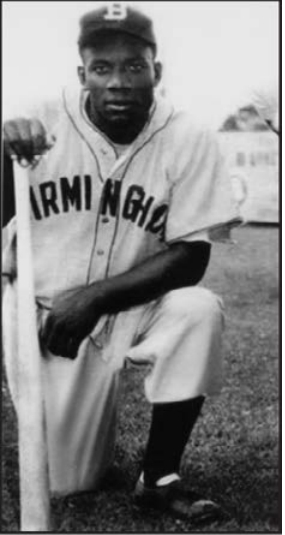

Ed Steele

Edward D. Steele was an Alabama fixture through and through. He was born in Selma on August 8, 1916, to Ezekial Steele and Viola Dawson, about whom nothing is known except that they were apparently married. Steele made it through the 10th grade before he began his own career both as a laborer and baseball star, eventually making his name as an outfielder for one of the Negro Leagues’ more successful franchises, the Birmingham Black Barons. The native Alabaman later settled in Birmingham, where he died in February 1974 at the youthful age of 57.

In his brief lifetime Steele made his presence felt in the baseball world. Though he was somewhat underappreciated as a player, he had an aura about him that made him an ideal fit as a manager, a position he filled quite well after his playing days came to an end.

Steele was known as Stainless Steele, though the nickname rarely shows up in contemporary publications. The play on words that involved both his last name and Birmingham’s big industry became his sobriquet early in his career, and Steele embraced it.

Birmingham was indeed the Steel City of the South in the first half of the twentieth century. Much of the city’s economy, from its dawning until after the Civil Rights era, was dependent upon steel processing and other warehouse-type industries. Many black ballplayers worked in the mines and steel mills by day and played their beloved game by night and on weekends.

Steele began his career as a player on the American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO) team, which was the pre-eminent squad in Birmingham’s Industrial League. Although not ACIPCO’s intent, the company’s team had so many outstanding players that it often ended up serving as a farm team for the Negro major-league teams, including the hometown Black Barons.

According to US Census data from 1940, it appears that Steele was joined in his household during those years by a wife, Glady Davis, who became Glady Steele. The couple had two daughters born a year apart, Elizabeth in 1930 and Ruby Lee in 1931. They lived in a rented house at 2405 18th Street in downtown Birmingham.

Steele was one of ACIPCO’s better players, and Black Barons manager Winfield Scott Welch snatched him away in 1942. In his nine seasons playing with ACIPCO, Steele recorded a .363 batting average that included three seasons in which he hit better than .400.1 In spite of his obvious talents, which included a strong arm and home-run power, Steele played sparingly in 1942 and 1943 before becoming a Black Barons regular in the 1944 season.

Available statistics show that Steele had nine plate appearances for the Black Barons in 1942, recording three hits and three RBIs while also walking once and scoring a run. Statistics for 1943 are even less complete, showing only five plate appearances in which he hit safely twice and drove in a run. Though his play was irregular in Welch’s first two seasons at the helm of the Black Barons, he had the support of his former ACIPCO teammate and future manager, Piper Davis, who recommended Steele as the ideal right fielder for the Black Barons based on their roster composition and the fact that they played their home games at Rickwood Field.2

At 5-feet-10 and 195 pounds, Steele was for that time a beast of a man. Those who saw him said he was blessed with a barrel chest, broad shoulders, and Popeye-like arms that enabled him to throw cannon shots from the outfield. He could stand in the outfield, catch a ball flat-footed, and still throw a runner out who was trying to tag up. There are tales of Stainless throwing runners out by several steps with a throw that never even came close to scraping the dirt.3

Perhaps Steele’s most important shot was fired in extra innings of Game Two of the 1948 Negro American League Championship Series. With the Black Barons tied with their nemesis, the Kansas City Monarchs, in the 10th inning, Steele’s arm came to the rescue of relief pitcher Bill Greason.

The reliever was fading fast, having entered the contest in the top of the fifth inning just a day after pitching in relief in the series’ inaugural game. With a Monarch on second base, Greason allowed a soft single to right field, where Stainless was loading up his cannon. In his book Willie’s Boys, John Klima describes the play:

“Ed Steele charged the ball and picked it up on a good hop. Steele’s shot to pigtail Pepper Bassett never touched the turf. As Baker raced home, his eyes widened when he saw Pepper waiting on him. ‘Edward Steele cut Baker down at the plate with a line peg for the most beautiful play of the game,’ the World reported. Said Greason, ‘Ed Steele had a great arm. I was glad he did.’”4

The Black Barons went on to win that important game, their second in a row, and eventually defeated the Monarchs to advance to the Negro League World Series against the Homestead Grays. Though they would end up losing the last such World Series ever to be played, Steele was a key cog who helped them to advance as far as they did in 1948.

In spite of the fact that Steele was known for his lethal throwing arm, he was not a premier defensive outfielder. Stainless often misplayed fly balls and line drives to the outfield, misjudging them or simply by being too slow to get the baseball.5 Having Willie Mays by his side in center field made Steele’s job easier in 1948. It did not matter if Steele was not fast enough to get to a ball hit to right-center, since that was Mays’s territory anyway.

Though Piper Davis had initially recommended Steele to former manager Welch, he was now unhappy about Mays’s uncanny ability to routinely mask Steele’s slow-footed efforts in right field. As the Black Barons’ new manager, Davis had no issue with Mays’s Houdini-like magic, but it did not sit well with him that Steele seemed to rely on the future major-league legend to make every play.6

Davis made his displeasure known to Steele, saying, “‘The ball goes out to right-center,’ Piper said to Steele. ‘I hear, ‘Come on, Willie!’”7 In fairness to Steele, however, Davis leveled the same accusations against Jim Zapp, the Black Barons’ left fielder in 1948. Though Davis appeared to believe that both players used Mays’s amazing ability as an excuse or justification for relaxing in the outfield, it may simply have been a case of an eager 17-year-old trying to cover as much ground as possible in order to make a good impression on his manager.

While Steele may have had adventures in the outfield, at the plate he was known for having a power swing, which was a rarity in that period of baseball when most hitters were content to slash the ball through the hole or to try their luck by going back up the middle. Steele wanted to make his own hole by placing the ball over the wall in one fell swoop. Since Steele had the potential to go deep at any time, Davis inserted him into the lineup as the team’s cleanup hitter.

Big Ed, the other nickname Steele went by, exemplified the premier slugger. During the incredible 1948 season, Steele and Davis held an impromptu home-run derby with the all-white Birmingham Barons’ first baseman Walt Dropo.8 It was a brash announcement on Davis’s part that the Black Barons were better than their white counterparts.

When Steele was not hitting balls over the wall, he was either being hit by pitches (being hit was one of his claims to fame in the league)9 or lining balls back up the box. Pitcher Bill “Fireball” Beverly once talked about Steele’s batting acumen:

They had a guy in Birmingham before I went there, Ed Steele. You can look him up. Steele was ’bout the best hitter I pitched against. He didn’t only hit me, he hit other pitchers. I don’t mean Texas leaguers — bloopers — a line! Everything he hit, you could hang clothes on it. Line drives. He hit one back through the box on me one time. I said, ‘I’ll get him out. I’ll throw the ball on the outside corner, as hard as I can throw it.’ He hit the ball right back up the center, hit me on the elbow and they thought he’d broke my elbow, but I shook it off and went on and finished the ballgame. He was one of the best hitters I faced.10

Steele’s power was perhaps amplified by the fact that, despite being a right-handed thrower, he hit from the left side of the plate. With his unusual power, he could simply flick his wrists and line one out the opposite way to left field, since that the fence in that direction stood just 321 feet from home plate. Conversely, he could also turn on a ball and jar it out of the yard to right field, where the fence was a mere 332 feet away.11 He did both with regularity.

Little is known today about who Stainless was as a person, but the legend of his hitting prowess lives on. He is often painted as a home-run masher. Other times he is seen as a consistent line-drive hitter. Available statistics show that Steele never hit below .300 in the Negro Leagues, which also happened to be his average in the 1948 NAL championship season.12 Omitting 1946, for which statistics are sparse, Steele never had an on-base percentage below .400 while playing in the Negro Leagues.

In addition to hitting for average and being a home-run threat, Steele was also a doubles machine. In his first full season with the Black Barons, he tied Neil Robinson for second in the Negro American League in doubles with 12. Two years into his career, Steele was asked to tour the country with the Satchel Paige All-Stars. During that 1946 tour he reportedly went 1-for-4 in his plate appearances.13 In 1947 he saw more action at the plate, going 4-for-16 against the Bob Feller and Ewell Blackwell All-Stars, but those numbers are unofficial. He played again for the All-Stars once more in 1948, and went 1-for-2.14

Before embarking on the traveling tour, Steele was also part of a rag-tag group of Negro League players, as well as one future major-league star, who challenged the Jackie Robinson All-Stars when they came to Birmingham. Piper Davis and Artie Wilson, two of the Black Barons’ best players, had left town to play winter ball in Puerto Rico, but Steele was still in town and was the longest-tenured veteran of the players who made up the team that challenged Robinson and Roy Campanella. Among the others on the Birmingham squad were Jimmy “Schoolboy” Newberry, Lyman Bostock, and Willie Mays, who, as the story goes, had to skip a day of high school to play in the game.15

Despite playing with the Satchel Paige All Stars from 1946 to 1948, it took until 1950 for Steele to gain his first East-West All-Star Game selection. In the game he batted seventh and played left field for the West team, going 2-for-3 while also driving in a run. As typified his defensive reputation, however, he also made an error in the field.

One season later, Steele was one of the biggest stars in the then-disintegrating Negro major leagues as he led all Negro League players in the East-West Game with a total of 10,019 votes.16 Playing in his second East-West All-Star Game in 1951, Steele hit fifth in the lineup and played right field, this time for the East squad. He was again a key contributor to an All-Star victory, as he tripled home a run and then scored on a double in the sixth inning, making him responsible for two of the East’s three runs in the victory. The man who would have been the All-Star Game MVP if such awards had been handed out then finally caught the eye of major-league scouts.

In 1952 Steele split time between the Triple-A Hollywood Stars and Class-A Denver Bears, two minor-league affiliates of the Pittsburgh Pirates. He hit just .213 for the Stars, but his average improved slightly when he moved down to the Single-A club, where he hit .254.17 Steele hit no home runs with Denver despite playing at the higher altitude; conversely, he played only 22 games for the Stars but hit two homers for that team.

Though Steele’s minor-league career was short-lived — it lasted just that one year — and unsuccessful, it was a victory that Steele had the opportunity to play the game alongside whites in 1952. When he began playing full-time in the Negro Leagues with the Black Barons in 1944, that idea had seemed implausible. Even though Steele was probably as good as any player the Birmingham Barons had, he could not have played for the whites-only Birmingham team. Such were the conditions of that era, especially in the Jim Crow South.

Steele was not ready for his career to end after his brief stint in the minor leagues, so he spent parts of 1953 and 1954 in Canada with the Intercounty League’s Galt Terriers. He rediscovered his power in 1953, and led the Intercounty League with 14 homers; however, no statistics are available for the 1954 season.18

Once his playing career was finally over, Steele returned to the United States in 1955 to manage the Detroit Stars, a Negro American League team with the same name as Detroit’s original Negro League franchise that had experienced its most successful seasons in the 1920s after being founded as a charter member of the Negro National League in 1919.

Steele managed the Stars for four seasons, through 1958, and was quite successful as a manager. In the 1956 season he led his Stars team to a 52-16 record (.765) and a Negro American League title.19 In all four seasons he managed the squad, he was elected manager for the East team in the East-West All-Star Game. He was 2-2 as a manager in those games, winning 11-5 in 1956 and 6-5 in 1958. The two losses were 2-0 in 1955 and 8-5 in 1957.20

Occasionally manager Steele would insert himself into the Stars’ lineup. In 1958, his last season in baseball, he hit .273 with an impressive .591 slugging percentage. In that season the Stars were renamed the Clowns. The Clowns played a doubleheader in Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, the closest he or many Negro League players would ever come to the big leagues.

After his retirement from baseball, Steele returned to his adopted hometown of Birmingham and became a barber. His shop was located on 4th Street in the downtown section of the city.21

In later years Steele seemed to be ambivalent about his baseball career. When he was asked to fill out a questionnaire, along with many of his Negro League compatriots, “he seemed shocked that someone remembered him. Like many Negro League ballplayers, his personal history was washed out like a faded photograph.”22

Though Steele has not been entirely lost to history, little information about him is known and his career has become an afterthought. Even in Birmingham, nary an Ed Steele-autographed baseball can be found at the city’s new Negro Southern League Museum. One of the greatest sluggers in Birmingham Black Barons history is all but forgotten in the place where he lived so much of his life and died in February 1974.

Steele died at the relatively young age of 57 due to several health complications. Shortly before his death, he had responded in the aforementioned questionnaire, “I will send some photos when I find my scrapbook. They moved it around when I was in the hospital. … I have a glove and a bat with my name on it if you want it.”23

All indications are that Steele was a calm, poised, and fun-loving gentleman throughout his lifetime. In nearly every available photo of him, he sports a smile or a poised neutral gaze. Steele fit the description of his former roommate, Piper Davis, as a religious man. If so, it is a pleasant description to summarize the life of a man who remains largely unknown.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, Forgotten Heroes: Edward “Big Ed” Steele (Birmingham: Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2012), 24.

2 John Klima, Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 39.

3 Klima, 159.

4 Ibid.

5 Klima, 165, 171.

6 Klima,152.

7 Ibid.

8 Klima, 121.

9 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 740.

10 Brent Kelley, Voices From the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 286.

11 “Rickwood Field,” baseballpilgrimages.com/rickwood.html, December 29, 2016.

12 Revel and Munoz, 24.

13 Revel and Munoz, 25.

14 Revel and Munoz, 12.

15 Allen Barra, Rickwood Field: A Century in America’s Oldest Ballpark (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), 159.

16 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 354.

17 Riley, 741.

18 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Bibliographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 155.

19 Revel and Munoz, 17.

20 Ibid.

21 Revel and Munoz, 19.

22 Klima, 269.

23 Ibid.

Full Name

Edward D. Steele

Born

August 8, 1916 at Selma, AL (US)

Died

February , 1974 at Birmingham, AL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.