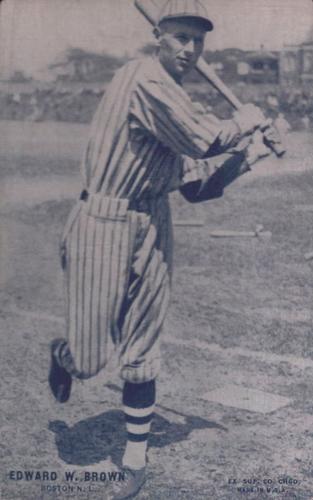

Eddie Brown

Eddie Brown was a great hitter and a superb defender for the New York Giants, Brooklyn Robins, and Boston Braves during the roaring decade of the 1920s. Over the span of 20 seasons in professional baseball, Brown patrolled all three outfield stanchions, covered first base one full season, and handled shortstop another. As a rural Nebraska youth, he was a catcher and later a successful pitcher. From start to finish, Brown could hit, run, cover vast amounts of turf, and consistently catch the ball. His Achilles’ heel was the oft-noted weakness of his throwing arm. The nickname “Glass Arm”1 (i.e., “a throwing arm stiff and kinky and utterly useless in a baseball way,”2 aka, “bursitis”3) frequently has been appended to his given name.

Eddie Brown was a great hitter and a superb defender for the New York Giants, Brooklyn Robins, and Boston Braves during the roaring decade of the 1920s. Over the span of 20 seasons in professional baseball, Brown patrolled all three outfield stanchions, covered first base one full season, and handled shortstop another. As a rural Nebraska youth, he was a catcher and later a successful pitcher. From start to finish, Brown could hit, run, cover vast amounts of turf, and consistently catch the ball. His Achilles’ heel was the oft-noted weakness of his throwing arm. The nickname “Glass Arm”1 (i.e., “a throwing arm stiff and kinky and utterly useless in a baseball way,”2 aka, “bursitis”3) frequently has been appended to his given name.

The Nebraska Signal on July 18, 1918, transmitted from the Kelly Field Eagle, when Brown was stationed at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas and playing in the Army League during World War I, that he had “…battered his way through the Central Association (1915-1917)…but a bad arm, due to a fractured right wrist, caused by a pitched ball, kept him out of the big show.”4 The Kelly Field briefing on Brown concluded: “ . . . [h]e’s a natural hitter…Brown is a slugger of the (Gavvy) Cravath type. He never makes a false motion at the plate, and seldom fouls one, a wonderful endorsement for his great eye…”5 Nine years later, another sportswriter, quoted in the Omaha Bee, opined on the import of Brown’s throwing capacity: “Many debates have raged over Brown. The experts disagree on him. His name brings up that old discussion of how much a weak throwing arm hurts an outfielder…[But h]ow many runs did he cut off by his great fielding plays?…[I]n Boston,…they talk about his batting rather than his weak arm.”6

Edward William Brown was born on July 17, 1891, in Milligan, Nebraska,7 the middle child of John and Antoine (Bartu) Brown. John was a carpenter in the building industry in Fillmore County, Nebraska.8 Eddie, at age 18, also was listed as a carpenter in the 1910 census, and again as a carpenter’s helper in 1920, while included as a member of John and Antoine’s household in both counts.9 Eddie graduated from high school in 1908 at Ohiowa, Nebraska, also in Fillmore County.10 The Ohiowa Ohiowan on June 25, 1908, reported on a “pick-up game” played at Daykin, Nebraska. Daykin, being the veteran squad, won 20-14. Brown caught for Ohiowa, and “…dug them out of the ground and pulled them out of the sky behind the bat.”11 Brown later converted to pitcher. The June 23, 1911, issue of the Nebraska Signal covered a game between the Milligan “dusky pillflingers” and the Ohiowa “husky clouters,” played in Ohiowa, that lasted 12 innings. “Eddie Brown was on the slab for the locals the entire route…Both pitchers were invincible until the last half of the twelfth, when Eddie won his own game by hitting one to the tall grass and circled the bases for a home-run…”12

The Nebraska Signal on July 31, 1913, reported that Brown was “now playing ball with the Norfolk [Nebraska] club.”13 According to the July 26, 1934, Thayer-County Banner-Journal (Bruning, Nebraska), Brown had been traded from Bruning to Norfolk “for a keg of beer.”14 The Norfolk Drummers were admitted to the Class D Nebraska State League in 1914.15 Rather than march with the Drummers on the eve of their professional baseball debut, Brown belatedly joined the ranks of the NSL Superior Brickmakers deep into the 1913 season. “[T]he first day he joined the club Eddie played shortstop and none other than Dazzy Vance pitched for the Superior team.”16 As a rookie, Brown hit .426 in 18 games. In the September 4, 1913, issue of the Nebraska Signal, it was reported that he had “signed a contract to play ball with the Superior club …for next season.”17

Brown hit .298 for the Brickmakers in 1914. The Superior franchise then folded and was sold, along with Eddie Brown, to Fairbury (Nebraska) for $400 “and a full set of old uniforms…”18 Brown was hitting .314 when he was sold the week of June 27 for $500 to Mason City (Iowa)19 in the Class D Central Association. His .294 batting average in 78 games in Iowa brought his combined season mark to .300. After two more seasons in Mason City, he had spent nearly five years stuck in Class D ranks. On December 14, 1917, he enlisted in the United States Army Air Service.20 He was assigned to the 178th Aero Squadron.21 Brown was honorably discharged on January 28, 1919, at the rank of corporal.22

Brown remained in San Antonio following his discharge from the Army and joined the San Antonio Bronchos of the Class B Texas League in 1919. The jump from Class D to B also promoted his batting average, which rose to .280, including five home runs. Further, Bronchos manager Mike Finn affirmed that “…he is the greatest outfielder in the minor leagues. …If he had an arm which could throw the ball to the plate from the outfield he would be in the big show today.”23

Eddie Brown’s 1920 campaign was the first of five 200-hit seasons that he would assemble at Class B or higher. As a center fielder, he had 22 assists, but committed 12 errors, fielding a mediocre .971. However, in late summer, he was summoned and rewarded with a big-league call-up by the second-place New York Giants, led by John McGraw. He appeared in three contests, getting eight at bats, and mustering a double for his first major league hit. Brown was used sparingly after starting the 1921 season as a regular for the Giants, largely because he was hampered by the recurrence of his throwing arm problem.24 He appeared in only 70 games at the plate, stroking 36 hits for a modest .281/.324/.359 hitting line and scoring 16 runs. He played in 30 games on defense, 26 in center field, recording 63 putouts in 68 chances, a sub-par .956 fielding percentage.

On December 17, 1921, Brown was one of four players, plus cash, traded to the Indianapolis Indians of the AA American Association, for Ralph Shinners. In early August 1922, the Nebraska Signal reported on Brown’s pole position in the eight-team American Association batting race. He was accelerating and cruising at a .375 clip, but Jay Kirke of the Louisville Colonels was doing the same and averaging .374.25 However, Glenn Myatt of the Milwaukee Brewers led the league in the end with a .370 mark; Brown collected 214 hits and closed at .338. Brown led the fourth-place Indians in batting average, hits, doubles, triples (tied), and was second in home runs and slugging percentage.

The 1923 Indianapolis Indians nose-dived to a next-to-last finish. Despite the woeful play of the Tribe, Eddie Brown continued to improve. Again, he led his team in batting average (.361), hits, doubles, and triples, and was second in home runs and slugging percentage. He recorded 428 putouts, and a .976 fielding percentage, all improvements over his 1922 season. Home runs were seldom swatted by the 1923 Indianapolis Indians. Brown’s eight round-trippers were second only to slugging teammate Ernie Krueger’s 17. However, one late-season blast by Brown was Ruthian and beamed by the Nebraska Signal on October 11: “Eddie Brown of the Indians crashed a home-run in the first game at Washington Park Sunday that…sailed over the high leftfield fence and out of the Park. Only three batters have cleared the high out leftfield fence with drives in the history of the Park. They are Babe Ruth, Ernie Krueger, and Brown.”26

In the 1923-1924 offseason, Indians teammates Brown and Krueger traveled to Cuba to play winter baseball. Brown played center field in 68 games divided between the Almendares and Marianao teams. One of his competitors that season was the great Oscar Charleston, who played for the also great Santa Clara team.27 The Nebraska Signal pictured Brown and Krueger, while playing in Cuba, and noted that Brown was to report for spring training with the Indians on March 9 (1924) at DeLand, Florida.28 The April 10 Signal summarized a New York Times special on a March 25 game between the minor league Tribe and McGraw’s Giants at Plant City, Florida: “…The Indianapolis minor leaguers beat the Giants 7-3 recently…The star for the winners was none other than old [32] Eddie Brown…McGraw…said recently that Brown would have been a great outfielder, if he only had had a stronger arm…[A]ccording to the Indianapolis people, Eddie’s wing has come back and his throwing today was much better than anything he showed with the Giants. The improvement is attributed to cold water treatment to the arm while Eddie was in Cuba this winter…”29

Forty games into the 1924 American Association season, on June 4, while hitting .327, Brown was traded by Indianapolis to the National League Brooklyn Robins, for Gene Bailey and Binky Jones. Coincidentally, he’d again join a team where Dazzy Vance would be his teammate, and on the mound in Brown’s first round with the Robins on June 5. Brown was slotted into the outfield along with starters Zack Wheat, and Tommy Griffith. He transitioned seamlessly. The Nebraska Signal stated: “Eddie has been slugging at a .350 clip this year. He was formerly with the New York Giants but a poor throwing arm kept him from staying in the big leagues at that time. This year his arm seems to have yielded to treatment as he has been throwing in fine shape and covering lots of territory in the field…”30 Quoting from the Indianapolis Star, the Signal reassuringly exhorted that: “…his arm is in much better condition than last season…”31

The July 10, 1924, Nebraska Signal contained an article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that denigrated Brown’s throwing arm, while exalting his other attributes: “Eddie can hit…No one…can deny this…Edward also can field. His sparkling one-hand catches and extreme steadiness in the outfield are becoming the talk of the circuit…But…Eddie’s pegging arm is far from being a good one…Brown’s wing is considerably below par.”32

In his own defense, Brown spoke directly with the Daily Eagle reporter, and addressed the issues affecting his throwing arm and the steps he was taking to resolve them, while expressing optimism:

“…There was a time when the trouble was in my shoulder. Now all the pain has settled down near my elbow. I’m having Doc Hart take care of it and I hope to gradually work the soreness out. I’m actually throwing better right now than I ever did in the regular season, and almost as well as I did in Cuba, last winter.

“The very fact that the pain was down in my elbow instead of my shoulder encourages me considerably. I am inclined to believe that my shoulder is well, while the elbow soreness is but temporary, brought on doubtless by the wet weather we have had this season…

“…When the hot days roll around I expect my hitting and everything to improve.”33

Brown, as a Robin in 1924, banged out 140 base hits in 114 games, 39 for extra bases, and compiled a .308/.345/.424 line. He fielded .975, with 311 putouts in 322 chances. Brown had become a big league regular with a pennant contender. To further improve the condition of his throwing arm, it was reported in the October 23, 1924 edition of the Houston Post that “…Brown…will undergo an operation on his wing this winter, and Robbie hopes that Brown will have recovered from his ailment by next spring.”34

The May 21 Nebraska Signal touted Brown’s first round-tripper of the 1925 season on May 13, a grand slam in the seventh inning at Ebbets Field, which secured a 9-8 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals.35 The win, however, was of little consequence. Manager Wilbert Robinson’s Robins fell from the lofty perch of their strong second-place finish in 1924, to an also-ran sixth in 1925. Although the Robins were flightless, the 33-year-old Brown soared. A model of consistency, he posted a .306/.332/.429 line, with a then major league career high 189 base hits, 55 for extra bases, and 99 RBIs. He fielded .972, while leading the National League in games played with 153, and led all center fielders with 448 putouts.

The September 24, 1925 copy of the Nebraska Signal echoed the high praise heaped on Brown by Robins manager Robinson in late season:

“He’s what I call a real ball player…He’s the best fly-catcher in either of the big leagues, … One thing that makes Brown a valuable player is that he’s in the game from beginning to the end whether the club is winning or losing. He’s working all the time.

“[H]e isn’t a grandstand performer nor a chaser after individual records…He’s what I call a model ball player, forgetting himself and playing for the good of the entire club. The game could well stand more players of the Ed Brown type…”36

Less than two weeks later, on October 6, 1925, the Brooklyn Robins traded Eddie Brown, along with Jimmy Johnston and Zack Taylor to the Boston Braves for Jesse Barnes, Gus Felix, and Mickey O’Neil. That same day, the 34-year-old Brown was in Indiana, marrying 33-year-old Minnie Lee (Purvis) Holbert.37

The 1925 Braves, under manager Dave Bancroft, had finished in fifth place. They fell to seventh in 1926, but Eddie Brown had the finest season of his major league career. He chain-sawed to a .328/.355/.415 line and a .770 OPS. He topped the National League in hits with 201, including a league-high 160 singles. He had top-10 finishes in games played, at bats, plate appearances, batting average, RBIs, doubles, total bases, outs per strikeout, and outs. Defensively, he characteristically fielded .968 in left, and .963 in center. Brown received 10 votes and finished 15th in the NL MVP consideration for the 1926 season.

Norman Brown, writing in the May 15,1926, issue of the Oswego (New York) Palladium-Times, assessed the Boston swap: “The trade has turned out beautifully for the Braves…Brown is not only hitting like a demon, but given free rein in his work, has turned out to be one of the best ball-hawks in the National League…”38

James J. Murphy proclaimed in the June 17 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, under the subheading “Players Call Brown The Greatest Ever,” that “…Brown is the greatest outfielder of the present day…(T)he Cubs…told many interesting tales of how Brown’s remarkable fielding had proved their nemesis…(e.g.,) Eddie raced to the scoreboard and plucked one of Riggs Stephenson’s prodigious wallops out of the air with his bare hand…The players, once they get to Boston, try to change their batting so that no fly balls are hit to Brownville…”39

However, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in its November 13, 1926, issue, launched harsh criticism at Brown’s weak throwing arm, contesting that “[o]pposing players took an extra base on any kind of a hit to centerfield, just as they had the year before when the tissue paper arm belonged to Brooklyn.”40 This Brooklyn sportswriter agreed that Brown should be retooled as a first baseman, as Bancroft was said to be considering.41 Brown would play one game at first base in 1927 and one in 1928—both errorless; all of his other games were played in the outfield.

On December 6, 1926, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, however, provided a less pungent, nonetheless, qualified endorsement: “Eddie can’t throw yet. But he can catch fly balls—and how! He can hit any kind of pitching hard and low-ball pitching to a fare-thee-well…Long before the season closed, Robbie, although he won’t admit it, was wishing that Long Eddie (6’3”, 190 pounds) was back at the old stand.”42

Not every sports journalist considered Brown’s throwing arm a liability greater than the sum of his assets. Irwin M. Howe, took exception in the Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal, as carried in the Fillmore Chronicle, December 23, 1926: “Eddie Brown of the Boston Braves has a weak arm…But what of it?…What he might have done with a strong arm is merely a matter of conjecture. Some of the strong arms ought to take lessons from this weak member.”43

On August 24, 1927, Eddie Brown played in his 534th consecutive game, establishing a then National League record. The September 8 issue of the Nebraska Signal chronicled the achievement, recounted from the Boston Post, when he had played his 542nd consecutive game: “He has made a remarkable fielding record in the league. He made 1,412 putouts and only forty errors in the 534 games. He has made only four errors this season. His batting average for the 534 games was .309.”44 However, Braves pilot Rogers Hornsby gave Brown a rare respite in early June 1928, ending his consecutive games streak at 618.45 From June 5, 1924, through April 28, 1926, he had played in 279 complete games, stringing together 2,543 consecutive innings played, ranking 17th on the all-time list.46

The 1927 Boston Braves recorded their second consecutive seventh-place finish, but 36-year-old Brown manufactured a .306/.340/.401 line and stole 11 bases, a career high. He led the major leagues in games played, 155, and fielded .981. A sportswriter for the Boston Traveler concluded that “Brown has played steady baseball for the Braves and but for a weak throwing arm would be considered one of the greatest outfielders in either league.”47

The 1928 Boston Braves derailed to a calamitous 50-103 record. Only the Philadelphia Phillies were worse. The now 37-year-old Brown experienced significant decline in his game, notably at the plate where his batting average tailed off to .268, his first time under .300 since joining the Brooklyn Robins. Further, he fielded just .960. The curtain dropped on Eddie Brown’s major league career. His final line was a consistent .303/.334/.400. For his career, he bagged 878 base hits, 649 being singles. He accounted for 732 runs, scoring 341 (16 on home runs) and knocking in 407.

In 1929, at age 38, Brown rolled back to the high minors and was an outfielder for the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association, managed by Casey Stengel. He hit .314 in 155 games. He then stepped down to the Class A Texas League in 1930, with stints at Dallas, Houston, and Ft. Worth. In 1931, Brown was with the Ft. Worth Panthers, where he played 161 games at first base, recording a .987 fielding percentage. At the plate, he notched 199 safeties, and batted .317. Brown went home to the Cornhusker State in 1932, at age 41, and played in 147 games for the Class A Omaha Packers of the Western League. He corralled 204 hits, the fifth and final time that he equaled 200 or more. His season batting average was .352. Brown also managed the Omaha team, his professional baseball career now presumably complete.

However, following a three-year hiatus from professional baseball, Eddie Brown came back to the diamond in 1936 at age 44, and managed the Fairbury Jeffs of the reincarnated Class D Nebraska State League.48 Together with Paul Hamman, Brown was also an owner and sponsor of the club.49 He conducted a training school in Fairbury for prospects to determine the team roster.50 When on the field, he recorded 19 base hits in 59 at bats for a final batting average of .322. He did not have any fielding statistics for the ill-fated Fairbury franchise, who along with Lincoln, shut down midseason.51 This was Brown’s last appearance in professional baseball. At all levels during his professional baseball career, Eddie Brown played in 2,403 games, batted 9,093 times, and rapped 2,852 base hits, unofficially a .314 clip, while connecting for 79 home runs. He amassed 3,751 total bases—64 miles of base paths.

Post-baseball, Brown moved to Marysville, California, in 1936. In 1942, he relocated and worked as a carpenter at the Naval Ammunition Depot (NAD) on Mare Island, until retirement. Brown was beloved and respected by his NAD colleagues, who hosted a dinner in his honor in 1949.52

Eddie Brown lived in Vallejo, California from 1942 until his death “due to carcinoma of [the] stomach,” at age 65, on September 10, 1956.53 Brown was married to Edna Taylor Pivinska, from Ohiowa, when he died.54 He was buried, with full military honors,55 at the Golden Gate National Cemetery, near San Francisco, California, on September 12, 1956.56 On September 27, 1956, a Nebraska Signal journalist and friend wrote that Brown’s death “was a deep shock.”57 Eddie had penned to the Nebraska Signal shortly before his passing, that he was going to have minor surgery, had retired as a carpenter from Mare Island, and “was now going to enjoy the many things of interest in California.”58

The nickname “Glass Arm” will be attached to Eddie Brown in perpetuity. However, on August 8, 1958, Hall of Famer Ty Cobb said, “I played about half my career with a glass arm…”59 And Brown’s former teammate, Dazzy Vance, also a Hall of Famer, experienced the same condition.60 Although a “glass arm” is detrimental to a baseball player, it is not always an impediment to greatness.

Eddie Brown was nominated for induction into the Nebraska Baseball Hall of Fame (NBHOF) in Beatrice, Nebraska, in 2021. In spring 2022, he was unanimously elected by their Board of Directors. One in a class of seven, Brown will be posthumously inducted into the NBHOF on November 13, 2022.

Author’s Note

Several sources state Brown played collegiate baseball at Syracuse University in 1920. However, he did not play at Syracuse in 1920, nor at any time.61 Instead, a G. Edwin Brown, who also went by Eddie Brown,62 did play collegiate baseball at Syracuse University from 1916 through 1920.63 G. Edwin Brown, a dual sport athlete, also played collegiate football for the Orangemen from 1915 through 1917.64

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin, Rory Costello, and Norman Macht, and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-almanac.com, Baseball-reference.com, SABR.org, and the Seamheads Negro Leagues database.

E-mail communication with, and digital newspaper clippings from Jack Major, major-smolinski.com

Telephone and email communications with Dorothy Novak, Fillmore County, Nebraska, historian, who shared the Digital Newspaper Archives, Fillmore County, Nebraska project, which led to scores of newspaper articles pertaining to the life and baseball career of Edward William Brown.

Notes

1 Jack Major, “Baseball nicknames: You gotta love ‘em,” http://major-smolinski.com/BSBLNAMES/OHTHATGUY.html

2 “Sport World with James J. Corbett,” Fort Wayne Sentinel (Fort Wayne, Indiana), October 26, 1918: 4.

3 Dr. William Brady, “Personal Health 3 Warnings Given Victims Of ‘Glass Arm’ Ailment,” Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), March 17, 1948: 19.

4 “Ed Receives More Praise,” Nebraska Signal (Geneva, Nebraska), taken from the Kelly Field Eagle, July 18, 1918: 8.

5 “Ed Receives More Praise.”

6 “Eddie Brown’s Ball Career,” Omaha Bee, reprinted in the Nebraska Signal, April 7, 1927: 10.

7 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/175599596/person/102275757701/facts

8 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/175599596/person/102275759755/facts

9 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/175599596/person/102275757701/facts

10 E-mail communication from Dorothy Novak, Fillmore County, Nebraska historian, May 3, 2021.

11 “Daykin Takes the Game,” Ohiowa Ohiowan, June 25, 1908: 8.

12 “Ohiowa Ohiowan,” Nebraska Signal, June 23, 1911: 4.

13 “Ohiowa Brevities,” Nebraska Signal, July 31, 1913: 4.

14 “History Will Be Revived In Bruning-Fairbury Tilt,” Thayer County Banner-Journal (Bruning, Nebraska), July 26, 1934: 1.

15 Nebraska Minor League Baseball by Community, http://www.nebaseballhistory.com/bytown.html

16 “Eddie Brown Almost 35 Years-Old,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 6, 1926.

17 “Ohiowa Spotlight,” Nebraska Signal, September 4, 1913: 10.

18 “Only Four Towns Now,” Fairbury Journal-News (Fairbury, Nebraska), July 1, 1915: 8.

19 Fairbury Daily News, July 15, 1915: 6.

20 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_2421406272_0450-00079?ssrc=pt&treeid=175599596&personid=102275757701&hintid=&usePUB=true&usePUBJs=true&_ga=2.263167884.1255464108.1621471211-1603221456.1617668598&pId=2149463

21 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_2421406272_0450-00079?pId=2149463

22 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2590/images/40479_2421406272_0450-00079?pId=2149463

23 San Antonio Evening News, August 7, 1919: 8.

24 “Community Club,” Nebraska Signal, November 17, 1921: 1.

25 “Ohiowa Brevities,” Nebraska Signal, August 3, 1922: 9.

26 “Over the Fence,” Indianapolis Daily Star, reprinted in the Nebraska Signal, October 11, 1923: 5.

27 Baseball Nicknames, http://major-smolinski.com/BSBLNAMES/OHTHATGUY.html

28 “Eddie Brown in Cuba,” Nebraska Signal, February 14, 1924: 1.

29 “News from Eddie Brown,” New York Times, recounted in the Nebraska Signal, April 10, 1924: 5.

30 “Brown Back to Big Leagues,” Nebraska Signal, June 12, 1924: 1.

31 “Brown Back to Big Leagues.”

32 “Eddie Brown at Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, reprinted in the Nebraska Signal, July 10, 1924: 6.

33 “Eddie Brown at Brooklyn.”

34 “Robins Make Plans Bolster Team For ’25,” Houston Post, October 23, 1924: 13.

35 Nebraska Signal, May 21, 1925: 7.

36 George Fristbrook, “Eddie Brown Diamond Ace,” Weekly Baseball Guide, reprinted in the Nebraska Signal, September 24, 1925: 1.

37 Brown family tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/175599596/person/102275757701/facts

38 Norman S. Brown, “Eddie Brown’s Body,” Oswego (New York) Palladiium-Times, May 15, 1926.

39 James J. Murphy, “Looks Right Now as Though Bancroft Handed Robbie ‘Pair of Straws’ Last Winter—Players Call Brown The Greatest Ever,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 17, 1926: 24.

40 “Suggest Him as First-Baseman,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 13, 1926: 2.

41 “Brown Has Sure Pair of Hands.”

42 “Eddie Brown Almost 35 Years-Old.”.

43 Irwin M. Howe, “Eddie Brown Has Weak Arm; What Of It?,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Journal, reprinted in the Fillmore Chronicle, December 23, 1926: 3.

44 “Eddie Brown’s Record,” Boston Post, recounted in the Nebraska Signal, September 8, 1927: 4.

45 Thomas Holmes, “Brown’s Broken Record May Be Tonic for Durable Brave,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 15, 1928: 34.

46 Trent McCotter, “Ripken’s Record for Innings Played,” SABR.org, https://sabr.org/journal/article/ripkens-record-for-consecutive-innings-played/

47 “Ohiowa Boy Ambitious to Capture National League Playing Record,” Boston Traveler, reprinted in the Nebraska Signal, August 4, 1927: 1.

48 Daykin Herald, (Daykin, Nebraska), April 10, 1936: 10.

49 “Will Decide On Size Of League,” Grand Island Daily Independent (Grand Island, Nebraska), April 18, 1935: 11.

50 “40 Youths Out For Fairbury Leaguers,” Daykin Herald, May 8, 1936: 1.

51 Nebraska Minor League Baseball, Nebraska State League, 1936, http://www.nebaseballhistory.com/nsl1936.html

52 “Ed Brown Honored,” Nebraska Signal, September 8, 1949: 11.

53 Certificate of Death, State of California, National Baseball Hall of Fame file, September 11, 1956.

54 Eddie Brown obituary, Alexandria Argus (Alexandria, Nebraska), October 4, 1956: 1.

55 “Eddie Brown, Baseball Star, Dies at Vallejo,” Nebraska Signal, September 27, 1956: 7.

56 Certificate of Death, above.

57 “Eddie Brown, Baseball Star, Dies at Vallejo.”

58 “Eddie Brown, Baseball Star, Dies at Vallejo.”

59 Jack Cuddy, “All-Time Great Finally Tells Secret Cobb Got ‘Glass Arm’ on Mound,” Miami News-Record (Miami, Oklahoma), August 8, 1958: 5.

60 “Dazzy Vance, Glass Arm Tyro, Is Now Strikeout King Of the Two Major Leagues,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 18, 1923: 50.

61 Grace Wagner, Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), Syracuse University Libraries, Syracuse, New York, May 7, 2021.

62 Wagner.

63 Syracuse University Baseball Letter Winners, Syracuse University Athletics. webarchive

64 Syracuse University Football Letter Winners, Syracuse University Athletics. webarchive

Full Name

Edward William Brown

Born

July 17, 1891 at Milligan, NE (USA)

Died

September 10, 1956 at Vallejo, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.