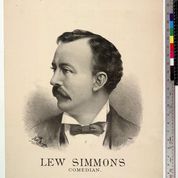

Lew Simmons

Lew Simmons was a popular performer as a minstrel entertainer both before and after his time in baseball management. One of many persons who linked the theater with nineteenth-century baseball, Simmons was a noted banjoist, a professional comedian of great repute, and an end man with the tambourine in the minstrel show.1 There is considerable evidence that Simmons was a baseball fan his entire life.

Lew Simmons was a popular performer as a minstrel entertainer both before and after his time in baseball management. One of many persons who linked the theater with nineteenth-century baseball, Simmons was a noted banjoist, a professional comedian of great repute, and an end man with the tambourine in the minstrel show.1 There is considerable evidence that Simmons was a baseball fan his entire life.

Simmons gave up minstrelsy when owning a baseball club offered better returns. Between 1882 and 1887, he embraced active partnership with Charles Mason and William Sharsig to own the Philadelphia franchise in the American Association. Simmons managed his club, represented its interests in the American Association, and represented the Association’s interests in its conferences with the National League to create what we know today as major-league baseball, or Organized Baseball, including the recognition of territory, respect for player contracts, an early form of player reserve, and a means to settle disputes. David Nemec observes, “[I]n AA councils Simmons was the most prominent in the ownership group. The presence of a successful professional comedian must have given a unique dimension to meetings of AA bigwigs. Simmons, not surprisingly, was a genial fellow always ready with a story, but was taken seriously in AA councils. …”2

Simmons was best recalled from that era as part of the triumvirate ownership group with Mason and Sharsig. He was the business manager of the pennant-winning 1883 club that captured the AA pennant in the most exciting pennant race to that point in baseball history. For Philadelphia baseball fans, Simmons sought another championship, but they had a long wait until the 1910 World Series champions under another owner and manager, Connie Mack, whose club Simmons passionately followed.

When the returns in baseball decreased, Simmons sold his economic interests in the Athletics. Failing in business, Simmons successfully returned to minstrel performances.

Simmons was born on August 27, 1838 at New Castle, Pennsylvania.3 In an early recollection, Simmons fell into the flooded Shenango River. At grave danger, P. Ross Berry, a teenaged African American, saved Simmons. Berry later settled in Youngstown, Ohio, and whenever Simmons visited Youngtown, he would visit with Berry in his rooms or at the theater. Simmons commemorated his fortune by wearing on his watch chain a personalized Masonic charm, the reverse of which was engraved with an African American man rescuing a White male child.4

By 1842, the family moved to Warren in northeastern Ohio, where his father, William, worked as a cooper, or barrel maker.5 There, Simmons experienced an event that shaped and guided him for the remainder of his life:

“When I was about 6 years of age my father took me to a circus and we stayed for the minstrel performance that closed the show. One of the players did a blackface stunt and played the banjo. That caught my youthful fancy. I had a fairly good singing voice and immediately took up the study of the banjo.”6

Simmons reflected, “[T]he instant I saw that man with the banjo, I told my father that some day I was going to play one, too.” Simmons’s father purchased a banjo for him.7 Simmons enjoyed a childhood of performance on stage and with music. He and a dozen other boys would rehearse a play, and then perform at a benefit. Around 1851, Ed Slocum arrived in Warren with a dream to manage a show, and quickly put together a minstrel trio that included young Simmons and his banjo.8 Slocum later became Simmons’s business partner during the 1870s.9

When Simmons was 13, the family moved to Massillon, Ohio, where he worked as a hotel bellboy, then sold papers on the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railroad. The family thereafter moved to Lockport, New York, near Buffalo and alongside the Erie Canal. There, Lew learned his father’s profession, that of a cooper.10

Ambitions beyond manual labor and town life led Simmons to seek fame and fortune as an entertainer. At 18 he left home to join Yankee Robinson’s Circus, then touring from Bloomington, Illinois.11 He was paid $20 a month for physical tasks, but Robinson allowed him to play the banjo in a small minstrel show if he put up the tent.12

At the end of the 1858 season, the circus broke up its tour outside Indianapolis, where Simmons spent the winter. The Empire Minstrels, one of those traveling troupes common in that time period, also broke up at Indianapolis around the same time, and Simmons learned from them how to improve his banjo play. When a funny banjo solo was met with audience disapproval, Simmons declared afterward, “That was a pretty bad reception, boys, but it don’t scare me. I’ll be at the top of the heap yet.”13 Simmons was determined to reach the top of his craft. In the spring of 1859, he moved to Detroit to play the banjo professionally at Beller’s Music Hall, where he earned $1 and four beer tickets a night.14 There was some interchange between theater and baseball in that era and Simmons was an example of the mixture.15 He claimed to have first played baseball at Detroit around 1859.16

Simmons returned home in 1859, but he was determined to make it on his own and in show business. By the summer, he left for New York City with his banjo and – just in case – his cooper’s tools.17 He began his full-time minstrel career on December 19, 1859, playing the banjo at Frank Rives’ Melodeon Theatre on 539 Broadway for $8 a week. Simmons was good enough that Rives quickly increased his pay to $15 a week, then put him on a year’s contract at $25 per week, three nights in New York, and three at Rives’ Philadelphia theatre.18 No more nightly earnings or beer tickets for Simmons! This move introduced Simmons to Philadelphia’s theater scene.

During the Civil War, Simmons sang popular patriotic songs and performed in burlesques in places like Boston, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia.19 He never mentioned military service in his interviews, and none was provided in his obituary.

Simmons continued to play baseball as an amateur during the 1860s, playing first in New York, then in Philadelphia, where he played games with the Athletic Club.20 Simmons joined the Athletic Club in 1865, and during 1866-1867, he claimed to have played in one of its nines against well-known amateur clubs like the Haymakers and the Mutuals.21 When Oakdale Park opened on July 30, 1866, Simmons later proudly noted that the record books showed he scored 10 runs and recorded an out in one game.22 This early association with amateur baseball was one he would often refer to when he became a baseball magnate, as if his old-time involvement in the game provided him with the credibility to be taken seriously by his partners, colleagues, players, press, and fans.

How did Lewis Simmons become involved in owning the Philadelphia Athletics? Some backstory. Billy Sharsig, Charles Mason, Horace Phillips, and Chick Fulmer – the shortstop – were at times partners in the 1881 version of the Athletics. These owners contributed to the transition of professional baseball in Philadelphia from unorganized and independent teams into a market controlled by organized baseball. This Athletics club was a member of the short-lived 1881 Eastern Championship Association. Much like associations other than the National League, its existence lacked stability.

After the season, the Athletics went on a Western tour and the team’s owners noted the large crowds that appeared for many of its exhibitions.23 Philly crowds were often large but the Eastern Championship Association was unstable, which likely led Sharsig and Mason to seek entry into the National League. In mid-August, Phillips met with William Hulbert and applied for admission of the Athletics; however, within two weeks, the Athletics withdrew the application and released manager Phillips.24

Soon after the departure of Phillips, Simmons joined the partnership with Mason, Sharsig, and Fulmer. As an amateur player of some repute, he likely jumped at the opportunity for a chance to own and manage a baseball team, especially given the risks he’d taken in show business. The Athletics soon became the Philadelphia entry in the new American Association.

How Simmons became an owner is not entirely clear. The most consistent story is that he partnered with Fulmer, Mason, and Sharsig after a $200 payment for Phillips’ quarter-interest.25 Simmons recalled, “I paid the three $200 in gold, and you should have seen them scramble to divide it.”26 Soon, due to political difficulties, Fulmer fled Philadelphia and surrendered his partnership interest. Rather than take a risk as an owner in a new association, Fulmer had signed a contract to play shortstop for the Cincinnati American Association club.27 The partnership of Sharsig, Mason, and Simmons became the famous triumvirate of the 1883 Athletics with Simmons often its most public representative.

Simmons became the business manager of the Athletics.28 Bill James describes the typical manager of the 1880s as “[a] young entrepreneur … Some of these, like Cap Anson, stayed in baseball until circumstances forced them out. But more of them, best represented by John Montgomery Ward, were on their way to some other destination.”29 Simmons had come by a different route. Except for the 1884 season, until 1887, sportswriters referred to him as manager of the Athletics, and this reference was clearly related to the business position.30 By early December of 1881, Simmons was established in the Athletics headquarters at 135 North Eighth Street, and plans were announced to erect a new fence and seating for 1,000 at the old-time Athletics home of Oakdale Park. Season tickets with a reserved seat were offered for $10, and they were reportedly going fast.31

Though Simmons claimed to have left minstrelsy after he became manager of the Athletics, neither engaged contractually with an organized company nor performing for a regular theater program, he continued to entertain for money. Akin to the modern speakers bureau, Simmons used his musical and comedic talents with his newfound fame as an Athletics club owner to offer his services as an event performer. After taking on the management of the Athletics, Simmons continued to perform with Thatcher’s Minstrels, on tour as late as May 1882.32

The triumvirate enjoyed early financial success. The partners split $15,000 at the end of the 1882 season. Simmons observed that his share of the profits exceeded the cumulative shares from the time he managed the theater.33 After the 1882 season, he appeared in benefits and toured with the Arch Street Opera House Minstrels.34

Simmons continued to play baseball, too. He was the captain of the troupe of Courtright and Hawkins’ Minstrels. The minstrels – in costume – defeated the Athletics 21-18 in an exhibition game on October 2, 1882, in front of 1,000 fans at Oakdale park.35

Seeking a pennant and greater profits, the triumvirate upgraded the 1883 Athletics with players who had National League experience. Simmons engaged Fred Corey (Worcester), Alonzo Knight (Detroit), Bobby Mathews (Boston), Mike Moynahan (League Alliance Philadelphia), Ed Rowen (Boston), and Harry Stovey (Worcester).36 Before the start of the 1883 season, the triumvirate incurred $15,000 debt to pay advance money, lease new grounds, and construct the enclosed stands.37 Using his show-business contacts, Simmons obtained a loan of $16,000 from Adam Forepaugh of Forepaugh’s Circus.38

The 1883 race was one of the first to have an uncertain outcome heading into the final week of the season. In 1902 Simmons reflected on how he tried to buy a pennant for his 1883 Athletics. Using the promise of gifts, he encouraged an opposing club to beat the St. Louis Browns, owned by Chris Von der Ahe, who had to add his own encouragement to the Athletics’ opponents:

“I was more or less superstitious. … I rounded up [the Pittsburgh players] and made a speech, saying that if they would win but one game in Saint Louis, I would buy each and every player a $25 overcoat. … They never got the coats – they did not win a game. …

“Von der Ahe telegraphed from Saint Louis that he would give a $50 suit of clothes to every man on the Louisville team if they beat us four straight. Henry Pank, owner of the Louisvilles, sent smiling Guy Hecker in against us that day and the man who is now selling groceries in Oil City certainly did pitch the ball the first game. … The next day was one to make angels weep.”39

To capture the pennant, the Athletics needed either a single win at Louisville in their final series of the season, or St. Louis to lose a game in their series against the Allegheny club:

“When I saw we were gone I rushed up to Pank and shouted loud enough to be heard all over the stand: ‘I will give you $1,000 cash to put a man we can hit in there tomorrow.’

“This, coupled with the fact that in the eighth inning with men on second and third and two runs needed to win the game, I had rushed out to Rowen at bat and promised him $500 for a hit which would score both men, set the people thinking I was crazy. I was almost crazy. …”40

Such behavior today would earn Simmons some grief from the league offices, including a permanent ban from Organized Baseball, but times were different then. Simmons fondly recalled the hit by Moynahan that scored the winning runs: “I was so near a nervous wreck that I didn’t even have enough voice to yell. … I gave a kid a dollar to chase that ball down for me, and I kept it for years.”41 Simmons had an appreciation for game relics before there were memorabilia collectors.

Their season was highly profitable, with the triumvirate splitting $51,000.42 From just two seasons of ownership, Simmons had cleared $22,000. More than the money, Simmons especially enjoyed the limelight brought to him as a baseball magnate and the adulation he received from Philadelphia’s baseball-crazed public. Politicians attended their games. Thousands of fans clamored to watch. Simmons truly loved being its fulcrum:

“I was in the game up to my neck and was having the time of my life, making money and friends and enjoying good things. Then I got too blooming ambitious – didn’t want only a million, but several million, all at once.”43

After the championship season, Simmons turned down a reported offer of $50,000 for his one-third partnership interest. He expected the Athletics to earn more than $75,000 in 1884.44 With his newfound wealth, Simmons purchased a $10,000 house and fruit farm in Vineland, New Jersey.45 And he closely supervised improvements to the ballpark’s grandstand and private boxes.46 However, 1883 was the high point in both the field and bank for his baseball work.

The triumvirate soon learned that the talent in other Association clubs was catching up with that on the Athletics. Increasing the competitive pressure, their National League competitor, owned by Al Reach, quickly improved under Harry Wright’s management. Wright’s club began its practice at the beginning of April 1884. Athletics players were seen around town but not always at their ballpark. An observer who appeared at Athletics Park to watch practice and discovered only two players present inquired why. Simmons answered that the players would practice “when we can control our team,” after April 15, when their contracts began.47

The 1884 baseball preseason was exciting, with lots of Hot Stove League intrigue, the entrance of a new major league, the Union Association, and franchise expansion in the American Association from eight clubs to 12. Simmons opposed this expansion.48 His opposition was likely due to increased competition for players, which would increase salaries and lower the level of available talent, reduce the number of home games, and require greater travel expenses. Simmons sought unsuccessfully to strengthen the Athletics by negotiating with players under contract to Union Association clubs, those players not subject to Organized Baseball’s reserve rules. He actively wooed Fred Dunlap, the former Cleveland superstar.49

In a major coup, Simmons separated Billy Taylor from Henry Lucas’s St. Louis Union Club.50 Although the Athletics management acquiesced to an Eastern League entry in Philadelphia, Simmons was on record as opposing it, and he appeared to understand fully well the likely degradation in his franchise’s value when the city already had League and Union Association competitors: “There is enough base ball in this city without it.”51

The Athletics’ 1884 season was disappointing both in the field (61-46, 14 games out of first place) and in its finances. These failures resulted in conflict between the owners and the players. Simmons blamed manager Lon Knight, whom he viewed as ineffective, and he announced that he would manage the Athletics in 1885.52 In what would become an unfortunately common management practice on his part, Simmons bad-mouthed the players. A postseason interview in Sporting Life was reprinted in other newspapers and caused a blowup in the baseball world.53 Simmons went full bore and publicly blamed Knight for poor management, complained that the players did not follow team rules, and said the club’s profits were down $20,000. Simmons blamed the team’s budding star Harry Stovey for at least one lost game:

“Lon Knight was too easy for a manager. The men were allowed too many privileges, and more than one game was lost that would have been won had the men been in proper condition. That story about Stovey being injured by a falling scaffold at Ninth and Chestnut streets was very lame. The simple fact is that Stovey was intoxicated and Knight refused to allow him to play.”54

With his reputation at stake, Stovey immediately replied in Sporting Life with a denial and an announcement that he would not play under Simmons.55 Now facing the loss of their star player, the partners Sharsig and Mason worked to contain the damage:

“There will be no more experiments, and Mr. Alonzo Knight will manage and Mr. Harry Stovey captain the team. Under the circumstances the prospects we consider very flattering. Mr. Simmons’ claim that his management won the championship in 1883, was simply one of his midnight dreams.”56

Simmons did not back off and replied, “Facts are facts and speak for themselves.”57 Self-reflecting on his own hubris, he connected his thoughts of his importance within minstrelsy to those of player threats to not play for him:

“The trouble is with the players, they think they’re indispensable, but that’s where they make a grand mistake. Suppose Stovey or Knight should die, would the Athletic Club stop playing ball? Well, I guess not. I had that idea myself when I left the minstrel business, but the sun rises and sets just the same, and the show keeps moving along without me.”58

From the end of the 1884 season, there was little evidence that Simmons performed on the stage. Instead, he focused on managing the Athletics. Simmons managed the 1885 Athletics and Stovey played for him. That season Simmons again spoke ill of his players. Some, he said, failed to earn their salaries and others he threatened to release.59 His remarks failed to have the desired effect, and the triumvirate were dissatisfied with the playing outcome of the 1885 season. Sporting Life wrote that Simmons suffered “an uncontrollable temper.” There was a push to replace him with a professional baseball manager, and Sporting Life opined that the Athletics could do worse than Frank Bancroft. This was ironic. According to Sporting Life, Bancroft was an excellent business manager, but the triumvirate already enjoyed good home revenues and received their guarantee for road dates, therefore Bancroft’s natural talents would be of no use. And even worse, his social skills were unsuited to player management.60

At the 1885-1886 winter meetings, a reporter for Sporting Life wrote of Simmons:

“Lew is original, usually has a good story to tell, and is for war with the League for breaking the Reserve Rule, etc., but he wants no trouble, consequently when he is shown that there will be sure enough trouble if the war comes, he is not for it yet.”61

Simmons appeared to be a person who said what was on his mind or what he believed in, but in the end, he was a team player. He expressed conflict, but he preferred to get along.

In preparing for 1886, the triumvirate shifted their strategy in composing a roster. As the National League Phillies improved with young talent developed under Wright’s tutelage, the triumvirate understood fully well how the reserve rule protected the Phillies’ investment in that development. The triumvirate resolved to sign fewer older and experienced players and instead sought younger talent. Those players who proved themselves, the triumvirate would reserve. This is a practice many clubs follow today: Develop a promising young roster, fill in the pieces with veterans, then start over. While Simmons was not in favor of the youth movement, he went along with the experiment.62

Simmons managed the 1886 club, but it was unsuccessful. In a seemingly frenetic attempt to win, Simmons gave prospects regular tryouts and released underperforming contracted players, continually reordering the Athletics lineup.63 With the team suffering through a stretch of losses during a midsummer road trip, a correspondent reported, “Lew Simmons remarked to me the other day that he wouldn’t know how to feel if his boys would happen to win the game.”64 As the losing took its toll on him, Simmons reportedly lost 20 pounds.65 The Sporting Life correspondent exclaimed, “It’s worth the price of admission to sit within range when his club is getting the worst of it, and particularly when the boys make bad blunders.”66 Simmons again used the press to embarrass his players. He said that he would play in a game because he and Sharsig “can improve upon the work of the regular club batteries.”67

After the 1886 season, the triumvirate declared the youth movement experiment a success Younger players like second baseman Lou Bierbauer and catcher Wilbert Robinson were quickly developing into effective starters.68 However the work of their free-agent veterans (Joe Start and George Bradley) was judged unsatisfactory. Simmons came around, too: “Old players, why, they’re chestnuts.”69 Other clubs took notice and some sold their rights to veterans and signed younger talent.70 Heading into the 1887 season, Simmons provided public support for this strategy:

“I don’t take as much stock in ‘old blood’ as some people do, for I think young fellows if properly handled and if they have had some fair experience, can do just as well as anyone. We have got a good bit of new blood in our team for the coming season and we are going to do excellent work.”71

The 1886 season proved to be Simmons’s last in the Athletics’ business management; Mason and Sharsig blamed him for the poor financial performance at home games.72 It was very likely Simmons had too many other responsibilities, including his vaudeville and minstrel performances, for him to be successful in baseball management during the 1886 season.

Simmons was not independently wealthy, so he lived off what he earned as an owner. When the club neither paid its own expenses nor provided him income, he decided he had to sell his interest. However, once he sold his economic interest in the Athletics, Simmons was unable to get back into Organized Baseball. There is evidence that he tried to reenter baseball, his name linked to a new American Association league with a franchise in Philadelphia, but nothing eventuated.

Simmons continued to be a baseball fan in general. He wasn’t just partial to the Athletics. When his Athletics were on the road, Simmons was often at the National League park, where he could be found in his favorite seat in the top row of the lower deck of the pavilion.73 He was often noted as present at the team’s Opening Day ceremonies.74

Unlike Sharsig, who had a long and professional career in Organized Baseball, Simmons’s flame burned bright and fast. While he was in baseball, he was the most visible and active of the triumvirate.

The Reach guides show that Simmons held the offices of secretary in 1883, secretary and treasurer in 1884, secretary in 1885, secretary and manager in 1886, and president in 1887.

A review of the American Association guides shows that Simmons was a director of the Association in the seasons of 1882, 1883, 1885, 1886, and 1887, the Association’s vice president in 1884, and a member of the schedule committee in 1885 and 1886.

Simmons was both a leader and an innovator. In 1906 he claimed that he introduced the practice of making more than one ball available for a game. He noted the custom of playing with a single ball and the time spent waiting by players and fans for the return of the ball when the batter hit it into the stands or out of the park. With a bit of humor, Simmons stated:

“In a moment of brilliant inspiration it occurred to me that we might as well have two balls in the game, so that if one was put out of play the other could be used. I reasoned that it was a waste of time for some 15,000 spectators to play thumbs while the ground keeper was digging a lost baseball out of the tall grass, so I surprised the fans by introducing two balls. It made a great hit, and I was voted a good fellow and a very smart man for having thought of it. I always will believe that for this one thing alone the fans of the country owe me an inexhaustible debt of gratitude.”75

In addition to the extra ball, Simmons claimed two additional innovations. One related to fan experience: He had a net placed behind the home-plate area to protect spectators from passed and batted balls. The other was a change in the rules which penalized the pitcher for striking the batter with a pitched ball.76

A change in the rules that Simmons did not later claim, but one in which he clearly had a role, was the elimination of the foul bound, which called it an out when a foul ball was caught on the first bounce. Once on record favoring the foul bound, Simmons changed his view and seconded the motion to end the foul-bound rule.77

After selling his interest in the club and losing money on a failed baseball tour of Cuba, Simmons cast about for something permanent. He worked briefly for a machine-oil firm78 and for a book publisher.79 He also operated cigar stores and opened a saloon, all the while keeping an interest in show business.

Family Life

On September 9, 1863, Simmons married Mary Blaber, about 18 years old, in New York City.80 Their 10-week-old daughter, Mary, died on November 30, 1868, of capillary bronchitis.81 A son, Lewis Jr., also died.82 Mary died on April 26, 1897, of pneumonia, at the age of 51. An adopted daughter, Anna Francis, survived.83 When 20 years old, Anna married Charles B. Connolly on September 2, 1903.84 Anna and Charles produced a large family.

On May 13, 1905, Simmons, then 66 years old, married Sarah “Sallie” Rhoda, 40, of Allentown, in Philadelphia, where he lived at 17 North 60th Street.85 His comedic minstrel sketch first performed during the winter of 1897-1898, was “Sally Is the Girl for Me,” which could be a coincidence. Once married, Simmons and Sallie lived in Allentown at 501 N. 8th Street.86 Sallie died on February 10, 1920.87

Simmons was related to two professional baseball players. Joe Quest, a member of the 1886 Athletics, was also from New Castle, Pennsylvania. Simmons was related by marriage to Arlie Latham of the St. Louis Browns;88 he was the uncle of Latham’s wife.

Simmons was a member in Philadelphia’s LuLu Temple Ancient Arabic Mystic Shrine, which had 2,000 members,89 and also an active member of the fraternal organization the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.90 As a founding member of Philadelphia’s “Jolly Corks,” its members, including Simmons, founded Lodge No. 2 at Philadelphia on March 12, 1871.91 Simmons was said to visit with the Elks lodge wherever one was located at the place he performed on tour.92

Simmons’s life ended violently. While on the vaudeville circuit tour performing his comedic sketch Get on The Band Wagon, Simmons was in Reading, Pennsylvania, as part of a program at the Orpheum Theatre. On September 2, 1911, during the busy noon hour, he walked to his hotel to meet his wife, Sallie, who usually traveled with him when he was on tour. As he crossed the street, Simmons was struck by an ice team being driven the wrong way in the street. According to one eyewitness report, one of the horses struck Simmons in the face and the wagon crushed his ribs.93 All accounts report that a moment after he was knocked down, he was struck by a brewery truck. Loaded with beer kegs, the truck dragged Simmons up to 50 feet. Simmons’s injuries included a broken right leg, a fractured left arm, a crushed breast, and the splintering of every rib on his left side.94 Simmons died five minutes after admission to the Homeopathic Hospital.95 For the cause of death, the death certificate says, “Accidentally killed by being run over by an automobile. Shock, fractures, and internal hemorrhages.”96 Simmons was buried in Fairview Cemetery in Allentown.97

Acknowledgments

For sharing information, thoughts, and ideas, I thank James E. Brunson III, Richard Hershberger, Tom Shieber, L.M. Sutter, John Thorn, and Robert Warrington.

Sources

Sources included the following:

Achorn, Edward. “The Minstrel Star,” in The Summer of Beer and Whiskey (New York: Public Affairs, 2013).

Le Roy, Edward. “Lew Simmons” (obituary), New York Clipper, September 16, 1911.

Reach’s Official American Association Base Ball Guide for 1883 to 1888.

Sutter, L.M. “‘I’m an Actor, You Bet’ (1888),” in Arlie Latham: A Baseball Biography of the Freshest Man on Earth (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 86.

Notes

1 “Toboyne Township,” Newport (Pennsylvania) News, August 28, 1886: 8; “Old-Time Minstrels,” Philadelphia Times, November 27, 1887: 6.

2 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900: The Hall of Famers and Memorable Personalities Who Shaped the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 180-181.

3 “Lew Simmons,” New York Clipper, September 16, 1911.

4 “Lew Simmons’ Close Call,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, April 3, 1901: 12.

5 Brothers Dallas Simmons (8 years) and Thomas Simmons (4 years) were recorded born in Ohio in the 1850 Census. United States Census, 1850, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MX3Z-QBM, accessed July 2020.

6 “Sport Comment,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 2, 1910: 8.

7 “Lew Simmons at the Orpheum,” Allentown Leader, September 28, 1909: 1.

8 “Years of Burnt Cork,” Philadelphia Times, September 10, 1893: 16.

9 “Seen and Heard in Many Places,” Philadelphia Times, October 19, 1895: 8.

10 “Lew Simmons at the Orpheum.”

11 “Old Yankee Robinson,” Bloomington (Illinois) Pantagraph, September 13, 1881: 4; “Sport Comment,” St. Louis Star and Times, February 2, 1910.

12 “Lew Simmons at the Orpheum.”

13 “Years of Burnt Cork.”

14 “Years of Burnt Cork.”

15 L.M. Sutter, Arlie Latham: A Baseball Biography of the Freshest Man on Earth (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 86.

16 “Won Quakers’ Only Pennant,” Detroit Free Press, April 10, 1902: 9.

17 “Lew Simmons at the Orpheum”; “Sport Comment.”

18 “Years of Burnt Cork”; “Lew Simmons at the Orpheum”; “Sport Comment.”

19 “Years of Burnt Cork”; Philadelphia Times, April 5, 1895: 34.

20 “Veteran Baseball Player Tells How Athletics Won the Pennant,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 16, 1910: 10.

21 “Won Quakers’ Only Pennant”; “Sport Comment.” Simmons played baseball on ice skates for the Athletics during the winter of 1866-1867. New York Clipper, January 6, 1883.

22 Philadelphia Times, August 7, 1887: 14.

23 Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1881 Eastern Championship Association,” Baseball Research Journal (SABR), Spring 2019, volume 48, number 1: 78-85.

24 Brock Helander, “Prelude to the Formation of the American Association,” https://sabr.org/research/prelude-formation-american-association. Al Reach soon hired Phillips in late October to manage the 1882 Phillies, who would become a member of the League Alliance after Reach was outmaneuvered for a franchise in the American Association. Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1882 League Alliance,” Baseball Research Journal (SABR), Fall 2019, volume 48, number 1: 105-124.

25 “Base Ball,” Nashville Tennessean, December 13, 1886: 8; “Won Quakers’ Only Pennant”; “How He Won the Pennant,” Butte Miner, April 15, 1902: 9, printed in the Pittsburgh Dispatch; “Sport Comment”; “First Owner of Athletes Here,” Spokane Spokesman Review, May 28, 1910: 14. See Sutter for a summary of other stories recorded over the years.

26 “How He Won the Pennant.”

27 Fulmer was reported to be in political difficulties that necessitated his leaving Philadelphia. See “Sporting Business,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 14, 1882: 2. A sportswriter claimed that Fulmer, who aspired to have a career in Philadelphia politics, had to leave town due to his conflict with two influential political leaders. “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23, 1909: 15; November 24, 1909: 10; “Clean Sport a Good Investment,” Butte Daily Post, December 16, 1909: 7.

28 “Sporting Matters,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, November 29, 1881: 4.

29 Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers from 1870 to Today (New York: Scribner, 1987), 19.

30 “Lew Simmons will hold on to the management of the Athletic club, notwithstanding the frequent reports to the contrary.” “Sporting Topics,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Herald, July 17, 1882: 1.

31 “The Athletic Nine,” Philadelphia Times, December 4, 1881: 2.

32 “Amusement Notes,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, May 4, 1882: 4.

33 “Speed and Skill,” Buffalo Evening Republic, March 19, 1884: 1.

34 “Amusements,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, January 20, 1883: 1; “Sporting News,” Buffalo Evening News, March 31, 1883: 5.

35 Frank Moran, one of Simmons’ former minstrel partners, umpired. Sam Weaver and Jack O’Brien of the Athletics served as the minstrels’ battery. For the Athletics, an off-duty police officer pitched and Moran ordered him to provide slow tosses across the plate. “Minstrels Playing Baseball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 3, 1882: 2.

36 “Won Quakers’ Only Pennant”; “How He Won the Pennant.”

37 “How He Won the Pennant.”

38 James E. Brunson III, “A Mirthful Spectacle: Race, Blackface Minstrelsy, and Base Ball, 1874-1888,” NINE, vol. 17, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.

39 “How He Won the Pennant.”

40 “How He Won the Pennant.”

41 “First Owner of Athletes Here.”

42 “Sport Comment.” Sharsig’s obituary gives the amount as $63,000. “Mr. Sharsig Dead,” Allentown Leader, February 3, 1902: 2.

43 “Simmons,” Fort Worth Star Telegram, March 14, 1906: 7.

44 “Won Quakers’ Only Pennant.”

45 “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 23, 1884: 4.

46 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, March 2, 1884: 8.

47 “A Contrast,” Sporting Life, April 16, 1884: 5.

48 “Diamond Chips,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 6, 1884: 5.

49 “Diamond Chips,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 16, 1884: 8.

50 “Notes,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 11, 1884: 8.

51 “Forty-Eight Out of Sixty,” Wilmington News Journal, August 9, 1884: 1.

52 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, November 1, 1884: 3; “Base Ball Gossip,” Philadelphia Times, November 23, 1884: 8.

53 “Base Ball Notes,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Intelligencer, December 3, 1884: 3; “Base Ball Notes,” Detroit Free Press, December 7, 1884: 11.

54 “Lew Simmons Talks,” Sporting Life, November 26, 1884: 3.

55 “Harry Stovey Expresses Himself,” Sporting Life, December 3, 1884: 3.

56 “Trouble in the Camp,” Sporting Life, December 3, 1884: 3.

57 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, December 10, 1884: 5.

58 “Lew Simmons Talks.”

59 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 12, 1885: 5. “Diamond Dots,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, July 21, 1885: 1.

60 Sporting Life, September 2, 1885: 5.

61 “From the Falls City,” Sporting Life, January 13, 1886: 2.

62 “The Young Bloods,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1886: 7.

63 “Base Ball Briefs,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, June 21, 1886: 1; July 1, 1886: 1; “East vs. West,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 30, 1886: 2; “Hart’s Case,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 4, 1886: 5; “A Letter from Billy Explaining the Matter,” Chattanooga Daily Times, August 10, 1886: 5.

64 “From St. Louis,” Sporting Life, July 21, 1886: 4.

65 “Base Ball,” Camden (New Jersey) Morning Post, July 19, 1886: 1.

66 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, July 14, 1886: 8.

67 “The Diamond Sport,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 9, 1886: 6.

68 “The Young Bloods.”

69 “The Young Bloods.”

70 “The Young Bloods.”

71 “Local Ball Gossip,” Philadelphia Times, February 27, 1887: 11.

72 “The Athletic Club,” Philadelphia Times, November 7, 1886, 11; “Opening of the Season,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 31, 1887: 2.

73“All the Players in Good Condition,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 29, 1887: 9; “Won in the Ninth,” Philadelphia Times, August 26, 1887: 4.

74 “Who Were There,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 15, 1899: 10.

75 “Simmons,” Fort Worth Star Telegram, March 14, 1906: 7.

76 “Dean of Minstrels Was Pioneer of Baseball,” Seattle Star, January 2, 1909: 2. “The American Association,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1883: 2; “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 22, 1883: 672. At a special meeting in 1884, the Association directed the umpires to enforce the rule giving the batter a base when struck with the ball thrown by the pitcher. “That Special Meeting,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 20, 1884: 10.

77 “Base-Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 3, 1885: 8; Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1885: 3.

78 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, February 17, 1889: 16.

79 “Lew Simmons as a Book Peddler,” Wilmington Morning News, May 16, 1889: 4.

80 United States Census, 1860, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MCHP-P3H, accessed July 2020; “Lew Simmons.”

81 Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JKSW-36N, accessed July 2020.

82 United States Census, 1870, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MZRF-VGM, accessed July 2020. The 1867 city directory also provides this address. Ancestry.com, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database online], Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, accessed July 2020.

83 “Mrs. Simmons Dead,” Allentown Leader, May 7, 1897: 4; “Died,” Philadelphia Times, April 29, 1897: 5; “Lew Simmons Killed at Reading,” Allentown Morning Call, September 4, 1911: 11; “Lew Simmons.” David Nemec states that Mary gave birth to Annie in 1882. Major League Baseball Profiles, 180-181.

84 Pennsylvania Civil Marriages, 1677-1950, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QKJ4-3JWY, accessed July 2020.

85 New York, New York City Marriage Records, 1829-1940, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2489-2BN, accessed July 2020. See also, “Lew Simmons Married,” Allentown Morning Call, May 20, 1905: 5.

86 “Lew Simmons to Be Buried Here,” Allentown Morning Call, September 5, 1911: 5.

87 Sarah Elizabeth Rhoda, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LL3J-M9Q, accessed July, 2020.

88 “High Priced Horses,” Pittsburgh Press, March 1, 1886: 2; “Arlie Latham Dies at 93, Longest Living Player,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1952: 13.

89 “Mystic Shrine,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, March 7, 1892: 3.

90 Ellis, Charles Edward, An Authentic History of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (Chicago: self-published, 1910), 352.

91 “The Elks Are Now of Age,” Philadelphia Times, March 13, 1892: 4.

92 “Veteran Baseball Player Tells How Athletics Won the Pennant.”

93 “Old-Time Minstrel Man Is Killed on Street,” Reading Times, September 4, 1911: 5.

94 “‘Lew’ Simmons Killed,” New York Tribune, September 3, 1911: 7; “Minstrel Lew Simmons Killed by Auto Truck,” Tampa Tribune, September 5, 1911: 5.

95 “Old-Time Minstrel Man Is Killed on Street.”

96 Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania (State). Death certificates, 1906–1967; Certificate Number Range: 085971-089710, from Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1967 [database online], Provo, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014, accessed July 2020.

97 “Lew Simmons Killed at Reading”; “Lew Simmons Laid to Rest,” Allentown Morning Call, September 7, 1911: 10; Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records, from Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1669-2013 [database online], Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, accessed July 2020.Courtesy of John Thorn

Full Name

Lewis Simmons

Born

August 27, 1838 at New Castle, PA (USA)

Died

September 2, 1911 at Reading, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.