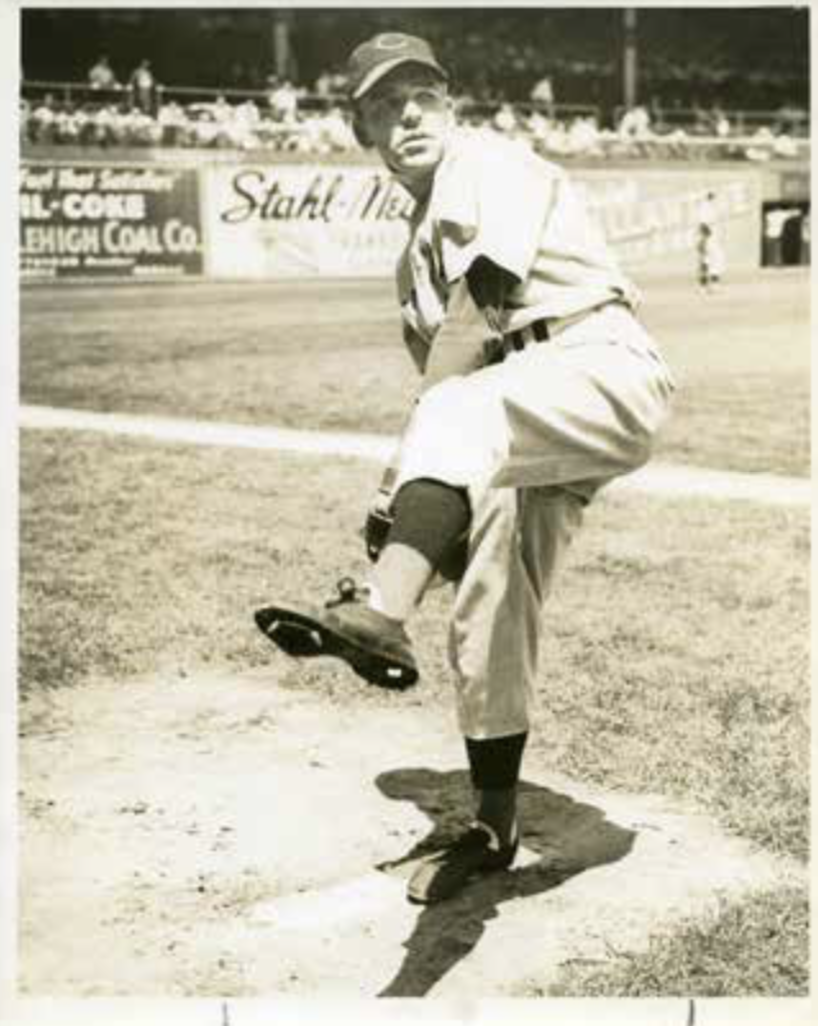

Elmer Riddle

Right-handed pitcher Elmer Riddle was from a mill town in Georgia, and is one of the few such players who did not enter the major leagues through the textile leagues. He was also half of a brother act in baseball, joining his brother, catcher Johnny Riddle, with Indianapolis in the minor leagues and Cincinnati and Pittsburgh in the majors. He had two wonderful seasons with Cincinnati, winning 19 games in 1941 and 21 games in 1943, before trouble with his pitching shoulder forced him to take a break from baseball. He returned with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1948 and had a good season, with a record of 12-10, before returning to the minors and then retiring in 1951.

Elmer, the son of James Ludy and Susan Rebecca Crosby Riddle, was born on July 31, 1914, in Columbus, Georgia. The family was large — Elmer had three sisters and three brothers. In 1920 his father, James, and brother Edward were working in the textile mills in Columbus, and his brother James was working as a traveling salesman. The Riddles were to become quite a baseball family. Besides Elmer and Johnny, Johnny’s son John L. Riddle spent several years in the minor leagues. Johnny and Elmer’s nephew Chase Riddle managed in the minor leagues, scouted for the Cardinals, and later was the longtime baseball coach at Troy University in Troy, Alabama.

James Ludy Riddle died in 1928, when Elmer was 13 years old. Johnny, 10 years older, looked out for Elmer during his teenage years, and made sure he had enough money to stay in school. By 1930 his 17-year-old sister, Lillian, was also helping to support the family by working in a candy factory.

Elmer first played baseball in high school, where he was a second baseman and not a pitcher. During high school, he had a weekend job as an auto mechanic. When he was 18, he married Lily Granberry, a native of Langdale, Alabama, who was known by her middle name, Inez. They were to have two daughters, Jane and Beverly. By 1935 he was working full time as a machinist. For several years he was a star on the Nehi Reds basketball team in Columbus. Nehi, the soft drink, was bottled in Columbus, and was made by the same company that bottled Chero-Cola, which was later to become Royal Crown or RC Cola. Elmer was apparently an attractive fellow. Various newspaper accounts after he debuted in the major leagues mentioned his “Hollywood profile,” his slate gray eyes, his even white teeth, his square jaw, and his ready smile.

In 1936 his brother Johnny, then playing for the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association, persuaded Elmer to join him in Sarasota, Florida, so he could coach him. Johnny’s coaching definitely helped; Elmer later said, “Johnny got me to lift my left leg higher when I threw, the idea being to get more of my body and weight into the delivery. It wasn’t long before I was throwing much faster.”1 Johnny got him a tryout with Indianapolis. By all accounts Elmer’s pitching was rather wild, but manager Wade Killefer felt that he showed promise, and signed him. He was sent to the Class D Wausau Timberjacks in the Northern League, where he finished the year with a record of 14-16, pitching 237 innings. His earned-run average was 4.25, and he struck out 183 batters, although he also walked 139. (Problems with control were to follow Riddle into the major leagues. In 1943 he was third in the National League in bases on balls, and in 1942 he was ninth. In 1948 he was second in the league in wild pitches, and in 1941 he hit five batters with pitches, fifth in the league.)

In 1937 the Indians sent Riddle to Charlotte of the Class B Piedmont League, where he won 13 games and lost 6, while cutting his walks down to 79 in 155 innings. He also went 2-2 for the Indians. He spent 1938 with Indianapolis and pitched in 32 games, mostly in relief. After the season Riddle was back in Columbus, again playing for the Nehi Reds basketball team and working for the bottling company, “good-willing at times, driving the routes at others and ‘generally making [himself] handy.’ ” 2 Elmer divided the 1939 season between Chattanooga, Durham, Birmingham and Indianapolis. He played the most games, 21, for Birmingham, where he had an 8-6 record and an ERA of 3.62. In September Cincinnati picked Riddle up from Indianapolis, and he made his major-league debut on October 1, the last day of the regular season. He appeared in relief, and pitched two scoreless innings. Apparently his new teammates knew him not as Elmer, but affectionately referred to him as Elmo.

Bill McKechnie was the Reds’ manager at the time. Known for his skill in managing pitchers, he brought Riddle along slowly. When Cincinnati won the National League pennant in 1939 and the World Series in 1940, Riddle was a seldom-used pitcher, appearing mostly in relief. The star pitchers for the team during those years were Paul Derringer and Bucky Walters. Riddle appeared in 15 games in 1940, starting only one. He finished the year with an ERA of 1.87. He made a brief appearance in the World Series, pitching one scoreless inning. With his World Series share he was able to build a nice home in Columbus, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Riddle had used that season of bench-warming to his advantage: “I sat on the bench through 1940 practically all the time. … But I studied the hitters and noted what Walters and Derringer would throw to them,” he said in 1942. “Those two, by the way, were swell. They were always willing to help me when I asked them something. By watching so much I learned a lot about the hitters. And then Jimmie Wilson [a veteran Reds catcher and coach] worked a lot with me. He taught me how to pitch. In the minors I had been nothing but a thrower, never studied the pitchers and pitched with a jerk. He taught me to lift my leg, throw my hips and body into the pitch, and make it smooth. That gave me control.”3

In April and May of 1941 Riddle pitched strictly in relief. When the Reds’ star pitchers began to falter, he emerged into a starting role, and became almost unbeatable, what one writer called “a pestiferous headache to all the batters in the National League.”4 From mid-June to mid-July he pitched seven straight complete-game victories. By the time of the All-Star Game he had nine straight wins. In 87 innings pitched in 17 games, he had allowed 72 hits and 21 runs, and had held opposing hitters to a batting average of .211. He had beaten every team in the league except Pittsburgh, which he had not faced. His manager, Bill McKechnie, expressed his anger that Elmer, with this fine record, had been passed over for the All-Star team. 5

By late July Riddle had 11 straight wins. Unfortunately for him, he was not playing for a pennant contender. As one sportswriter lamented, “This time a year ago, when the Cincinnati Reds were sailing along to their second straight National League pennant, Elmer Riddle would have been a baseball sensation. But Elmer was a year late. … He admits modestly that he owns 11 victories without a loss, and says, ‘I guess maybe I’ll do all right if my luck holds out.’ Elmer joined the Reds late in the 1939 season … and was around all last year without seeing much service except in relief jobs. … In spring camp this year Elmer still was just another mouth to feed, and it actually wasn’t until the current campaign was well under way that McKechnie looked around desperately for some help.”6

Riddle was quick to credit others with some of his newfound success. Besides Wilson, Walters, and Derringer, he praised Sheriff Blake, a former pitcher for the Chicago Cubs, who was at Birmingham with him and told him that he was striding too far. As a result, Riddle said, “When I shortened my stride my control improved. … Bucky Walters and Paul Derringer always tell me how to pitch to the hitters. … A fellow doesn’t have to have much stuff if he has perfect control and knows the hitters.”7 Ironically, in the same article, he mentioned that he had never had a sore arm and planned to be able to pitch in the majors for another ten years; that would all change three seasons later.

In a 1941 newspaper article, Riddle and two of the Reds’ catchers had interesting takes on what made him such a success. “ ‘His sinker’s what gets them,’ put in Catcher Dick West. ‘It’s his best pitch, I’d say. When it comes in around the middle, it breaks down and in on a right-hand batter. But when it comes in there around the neck, it takes off. It rises up and in then, instead of down. He must turn it loose a little different.’ ‘I’ll swear, I don’t know what it’s going to do,” Elmer confessed. ‘I just turn it loose, and it does things. All I hope is it keeps on doing whatever it’s doing.’ ” 8 In another article, veteran catcher Ernie Lombardi noted that “Little Elmo has everything — control, speed and a good hook. His main stock in trade is a swell sinker but his fastball is alive. It does things around that plate.” 9

In a 1941 newspaper article, Riddle and two of the Reds’ catchers had interesting takes on what made him such a success. “ ‘His sinker’s what gets them,’ put in Catcher Dick West. ‘It’s his best pitch, I’d say. When it comes in around the middle, it breaks down and in on a right-hand batter. But when it comes in there around the neck, it takes off. It rises up and in then, instead of down. He must turn it loose a little different.’ ‘I’ll swear, I don’t know what it’s going to do,” Elmer confessed. ‘I just turn it loose, and it does things. All I hope is it keeps on doing whatever it’s doing.’ ” 8 In another article, veteran catcher Ernie Lombardi noted that “Little Elmo has everything — control, speed and a good hook. His main stock in trade is a swell sinker but his fastball is alive. It does things around that plate.” 9

Riddle’s 11-game winning streak ended in a game against the Brooklyn Dodgers on July 23. But by August he had 15 victories and only two defeats. By the end of the season he had appeared in 33 games, starting 22 of them. He finished the season with the best winning percentage in the National League, 19-4. He gave up only 180 hits and 87 runs in 217 innings, and had a league-leading earned-run average of 2.24. He was the youngest pitcher ever to lead the league in both ERA and percentage (.826), and by accomplishing both in the same season, he joined the ranks of Grover Cleveland Alexander, Dolf Luque, Dazzy Vance, Ray Kremer, Charlie Root, Lon Warneke, Carl Hubbell, and Bill Lee. (Johnny Riddle was also on the Reds’ roster in 1941. The brothers were to play together for the Reds again in 1944 and 1945.

After his 1941 season Elmer became a star in his home state of Georgia. He was named Georgia’s outstanding major-league that year by the Georgia Sports Writers’ Association. His hometown of Columbus declared October 9, 1941, Elmer Riddle Day, and honored him at a Junior Chamber of Commerce banquet. That offseason he once again turned to basketball, this time as the coach of the Nehi Reds. By late December the team was playing .500 ball. Riddle considered coaching basketball to be a much easier job than pitching, noting, “In baseball you have to figure out the weakness of each batter. In basketball you usually can stop a team by bottling up one or two players.”10

In 1942 Riddle was back with the Reds, appearing in 29 games, 19 of which he started. His record plunged to 7-11, The highlight of his season was a two-hit victory over the Philadelphia Phillies on June 20. His ERA rose to 3.69. After the season he did war work in a Columbus motor repair and electric plant.

After his mediocre 1942 season, 1943 was a banner year for Riddle. His 21 victories tied for the major-league lead. On June 6 he pitched a 14-inning complete game in a win over the Boston Braves. He followed this performance with three-hitters on July 7 and July 30, both against the Braves. The latter game was part of a doubleheader, and in the second game, Braves pitcher Charles “Red” Barrett also pitched a three-hitter. Riddle capped off the season with a one-hitter against the Pirates on September 12; he was on course for a perfect game until it was broken up in the eighth inning. According to the New York Times, “Riddle was superb. Marking up his nineteenth triumph, he retired the first twenty-two men in order but, with one out in the eighth, Bob Elliott smashed a line drive to the left center-field scoreboard.” 11 On September 26 Riddle secured his 21st win of the season with a four-hitter against the Braves. He was also playing good defensive ball. He made his first error in 102 major-league appearances on August 3. Even with all of his wins, however, he had a low strikeout-to-walk ratio of 69 to 107. He ended the season 21-11, with an ERA of 2.63. He tied for the most wins in the majors with Rip Sewell and Mort Cooper.

The next season, 1944, was to be very different for Riddle. In March he passed an Army pre-induction physical. The Army advised him to report to spring training while awaiting induction. Apparently he was never called up, because, according to United Press sportswriter Jack Cuddy, he started the season “like a burning haystack.”12 He soon began to complain of a sore shoulder, however, and made no more appearances after being removed in the second inning of a game on May 7. In four starts that season, he went 2-2, and had a 4.05 ERA. He spent a week in Philadelphia being treated by a muscle specialist, and when he returned to Cincinnati, he received diathermy treatments from the Reds’ trainer, Dr. Richard Rohde. He eventually underwent surgery for a calcium deposit in his right shoulder. By September, he was beginning to test his arm, hoping to be able to pitch again in 1945. But in March 1945 Riddle informed the Reds’ manager, Bill McKechnie, that he planned to stay in Columbus and continue working as a recreational director. He must have returned to the Reds at some point, however, as he appeared in 12 games that season. He started only three of them and was ineffective, with a 1-4 record and an 8.19 ERA. In March 1946, at his request, the Reds placed him on the voluntarily retired list.

Riddle returned to the Reds in 1947 and appeared in 16 games, starting three of them. He was hit hard, giving up 42 hits and walking 31 batters in 30 1/3 innings, and ended the season with a record of 1-0 and an ERA of 8.31. He was not satisfied with the way his comeback had turned out. Johnny Neun had replaced McKechnie as manager. Riddle told Pittsburgh sportswriter Les Biederman, “It was like starting all over again. … If McKechnie had been there, I could take my time in working my arm back in shape because he knew what I could do. But with Neun having so many young pitchers on the roster, I had to start from scratch with them and show him something. All year long I was a relief pitcher. But I never was much good at relieving. It takes me too long to warm up and I can’t pitch when I go in cold. … I became disgusted. I asked to be traded or sold. … The Reds asked waivers on me and Donie Bush [the owner-general manager of the Indianapolis Indians] advised the Pittsburgh owners to take me.’”13 In December the Pirates got Riddle for the waiver price of $10,000. His brother Johnny was also on the Pirates’ roster, and they would work for the Pirates for the next two years.

Riddle worked hard the winter before he joined the Pirates. He told Biederman: “All winter long I worked on my right shoulder. … I pushed basketballs up to a basket by the hour with my right arm to strengthen the muscles and then devised a system of my own idea. I took my right elbow in my left hand and kept pulling my right arm around my neck. I felt something crack once in a while, but when I started to throw, there was no pain and my arm felt good.” Biederman added, “Fortunately, Bill Meyer, the Pittsburgh manager, is a man of patience and he gave Riddle all the time he needed in spring training to get ready. … Riddle then tuned up by allowing only seven runs in forty innings of spring training pitching, the best record of any of the Pirates.”14

Riddle did well with the Pirates that year, working mostly as a starter. Indeed, Bing Crosby, part-owner of the team, termed his comeback the “greatest since Al Jolson.” Riddle turned out to be the Pirates’ ace.15 In his first game as a Pirate, on April 23, he shut out the Cubs on two hits. He won eight of his first ten games, pitching six complete games in a row. By the end of the season Riddle had pitched 11 complete games. He pitched three four-hitters, and was named to the National League All-Star team. He appeared in 28 games, finishing the season with a record of 12-10 and an ERA of 3.49, as the Pirates finished fourth in the National League with an 83-71 record.

The Pirates reversed those numbers in 1949, with a 71-83 record and a sixth-place finish. Hampered by a leg injury, Riddle appeared in only 16 games, 12 of them starts. Riddle’s record was only 1-8, and his ERA rose to 5.33. He made his final appearance in the majors on August 3, and the Pirates optioned him to Indianapolis to make room for pitcher Jim Walsh. According to the Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia, Riddle was never the same after injuring his leg. His major-league career ended with a 65-52 record. He pitched 1,023 innings in 190 games, gave up 974 hits and 458 walks, and had an ERA of 3.40 and a .556 won-lost percentage.

Riddle pitched in five games for the Indians before the end of the season, ending with a record of 1-2 and an ERA of 2.89. In 1950, at Riddle’s request, the Pirates released him outright to the Indians. Riddle said of Pirates manager Meyer, “I didn’t want him going out on a limb with me in Pittsburgh. I know what a job he has after finishing sixth last year and told Bill that I would like to get two more years in the majors, but not to carry me and hurt the club.”16 With Indianapolis in 1950 he pitched in 26 games and ended the season with an 11-9 record and a 3.04 ERA. He spent the first month of the 1951 season with the Indians, pitching in four games. He was ineffective, giving up 31 hits, 16 walks, and 18 earned runs in 17 innings for a 9.53 earned-run average. Riddle was released on May 16. In his seven seasons in the minor leagues, four of them before he came up to the major leagues and three after the Pirates demoted him, his record was 56-52, with an ERA of 3.23.

After Riddle quit playing baseball, he spent a short time as a scout for the Kansas City Athletics. By 1959 he was employed by the United Oil Company back home in Columbus. He worked for the company until he retired. He was active in the Rose Hill Baptist Church, where he was a deacon, chairman of the ushers, and member of the J.W. Howard Sunday school class. He died on May 14, 1984, and is buried in Parkhill Cemetery in Columbus. His wife, Inez, died on April 21, 1996, and is also buried in Parkhill Cemetery.

Sources

Ancestry.com (1920 and 1930 census information)

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

James D. Szalontai. Teenager on First, Geezer at Bat, 4-F on Deck: Major League Baseball in 1945. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2009.

Photo of Elmer Riddle courtesy of Thad Gregory.

2 Gayle Talbot (Associated Press). “Elmer Riddle Arrives Year Late for Redlegs.” In the Atlanta Constitution, July 19, 1941: 7.

3 “Bench-Warming Siege Thought Riddle-Making.” Times-Daily (Florence, Alabama), Jan. 26, 1942: 7.

4 Pat Robinson (International News Service). “Elmer Riddle, the Reds’ Ace, is National League Sensation.” Zanesville (Ohio) Signal, July 12, 1941: 6.

5 Coshohocton (Ohio) Tribune, July 8, 1941: 2.

6 Talbot, op. cit.

7 Robinson, op. cit.

8 Talbot, op. cit.

9 Robinson, op. cit.

10 Romney Wheeler. “Riddle States Cage Coaching is Simple Job.” Atlanta Constitution, Dec. 27, 1941: 11.

11 “Reds Win, 1-0, on Riddle’s 1-Hitter.” New York Times, Sept. 13, 1943: 23.

12 Jack Cuddy (United Press). “Today’s Sport Parade.” Coshocton (Ohio) Tribune, June 12, 1944: 12.

13 Les Biederman. “A New Riddle.” Baseball Digest, Sept. 1948: 19.

14 Biederman, op. cit.: 20-21.

15 Joe Reichler (Associated Press). “Riddle’s Comeback puts Pirates at Top.” Sarasota (Florida) Herald-Tribune, May 11, 1948: 7.

16 “Elmer Riddle Back in Minors.” Prescott (Arizona) Evening Courier, April 13, 1950: 4.

Full Name

Elmer Ray Riddle

Born

July 31, 1914 at Columbus, GA (USA)

Died

May 14, 1984 at Columbus, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.